Spinal stenosis, osteophytes and ligaments ossification

- Understanding Spinal Stenosis: Causes and Types

- Diagnosis of Spinal Stenosis, Osteophytes, and Ligament Ossification

- Treatment of Spinal Stenosis, Osteophytes, and Ligament Ossification

- Differential Diagnosis of Spinal Stenosis Symptoms

- Potential Complications of Spinal Stenosis

- Prevention and Lifestyle Considerations

- When to Consult a Spine Specialist

- References

Understanding Spinal Stenosis: Causes and Types

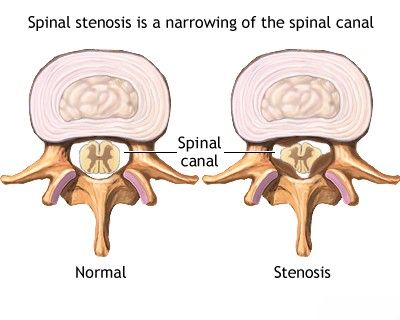

Definition and Common Locations

Spinal stenosis refers to a narrowing of the spaces within the spine, which can put pressure on the nerves that travel through the spinal canal and the intervertebral foramina (nerve root exit canals). This narrowing can compress the spinal cord itself (in the cervical and thoracic spine) or the nerve roots of the cauda equina (in the lumbar spine). Lumbar spinal stenosis is the most commonly recognized form, but stenosis can also occur at the cervical and, less frequently, the thoracic levels of the spine.

Pathophysiology: Osteophytes, Ligament Ossification, and Other Factors

Spinal stenosis is often associated with congenital (present at birth) or, more commonly, acquired anatomical changes affecting the vertebrae, intervertebral discs, facet joints, and ligaments that contribute to the formation and stability of the spinal canal. Key factors leading to narrowing include:

- Osteophytes (Bone Spurs): Degenerative changes (spondylosis) lead to the formation of bony outgrowths from the vertebral bodies or facet joints, which can protrude into the spinal canal or neural foramina.

- Ligament Hypertrophy and Ossification:

- Ligamentum Flavum Hypertrophy: The ligamentum flavum, located at the back of the spinal canal, can thicken and buckle inward with age and degeneration, reducing canal space.

- Posterior Longitudinal Ligament (PLL) Hypertrophy/Ossification (OPLL): The PLL runs along the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies. Its thickening or ossification (turning into bone) can significantly narrow the anterior part of the spinal canal, especially in the cervical spine. The normal thickness of the PLL should not exceed 2 mm, and the ligamentum flavum normally should not exceed 3-4 mm.

- Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Loss of disc height can cause the vertebrae to settle closer together, potentially leading to ligamentous buckling and foraminal narrowing. Disc bulging or herniation can directly compress neural structures.

- Facet Joint Arthropathy (Spondyloarthrosis): Degeneration and hypertrophy of the facet joints can lead to enlargement of these joints, encroaching on the spinal canal (central stenosis) or the lateral recesses and neural foramina (lateral recess/foraminal stenosis). Thickening of the facet joint capsules also contributes.

- Spondylolisthesis: Slippage of one vertebra relative to another can narrow the spinal canal.

- Congenital Stenosis: Some individuals are born with a congenitally narrow spinal canal, making them more susceptible to symptomatic stenosis with even mild degenerative changes.

- Trauma: Fractures or dislocations can lead to acute or chronic stenosis.

Narrowing of the spinal canal's cross-sectional area can result from either the enlargement of bony structures (e.g., laminae, articular processes, posterior vertebral body osteophytes) or from vertebral body flattening and displacement into the spinal canal.

Types of Spinal Stenosis (Central, Lateral Recess, Foraminal)

Spinal stenosis can present with circumferential (overall) narrowing, but anteroposterior (front-to-back) narrowing of the spinal canal is more frequently observed and clinically significant. Spinal canal stenosis may involve multiple vertebral levels or be localized to a single level. It is classified based on the anatomical location of the narrowing:

- Central Canal Stenosis: Narrowing of the main spinal canal where the spinal cord (cervical/thoracic) or cauda equina (lumbar) resides.

- Lateral Recess Stenosis: Narrowing of the lateral part of the spinal canal, just before the nerve root exits through the foramen.

- Foraminal Stenosis: Narrowing of the intervertebral foramen (neural foramen), the opening through which spinal nerve roots exit the spinal canal. This can be further divided into intraforaminal (within the foramen) and extraforaminal (just outside the foramen) stenosis.

Anteroposterior narrowing of the spinal canal may result from acquired stenosis (degenerative changes), hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum, or spondylolisthesis. Diagnosis of spinal canal stenosis often requires measurement of the canal diameter in the sagittal (side view) plane on imaging. For example, in the lumbar spine, absolute stenosis is often defined as a sagittal diameter of 10 mm or less, while a diameter of 10-12 mm (or sometimes up to 15mm depending on source) indicates relative stenosis. Similar measurements are used for the cervical canal.

Educational video discussing Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy, a consequence of cervical spinal stenosis.

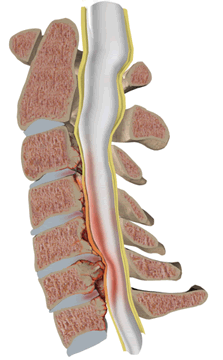

Image illustrating cervical spinal canal stenosis. The spinal cord is compressed due to degenerative changes of spondylosis and hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum.

Clinical Manifestations and Neurogenic Claudication

Lumbar spinal stenosis involves chronic compression of the cauda equina nerve roots (the bundle of nerves at the end of the spinal cord). It can occur due to congenital narrowing of the lumbar spinal canal, which may be exacerbated by disc protrusion and degenerative spondylosis.

A hallmark symptom of lumbar spinal stenosis is **neurogenic claudication**. This is characterized by:

- Pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness in the buttocks, hips, thighs, and calves.

- Symptoms are typically provoked or worsened by walking or prolonged standing (spinal extension).

- Symptoms are usually relieved by rest, sitting, or leaning forward (spinal flexion), which temporarily increases the space within the spinal canal.

These symptoms can mimic intermittent claudication of vascular origin (due to peripheral arterial disease), necessitating a vascular surgery consultation and vascular ultrasound to rule out arterial insufficiency. In neurogenic claudication, peripheral pulses are typically normal, and exacerbation of pain during activity may be accompanied by diminished deep tendon reflexes and sensory deficits in the legs.

Lumbar spinal stenosis and cervical spondylosis often coexist in patients. Cervical spondylosis with myelopathy may provoke periodic muscle spasms and fasciculations (twitching) in the legs, in addition to neck pain, arm pain, weakness, and sensory changes in the upper extremities.

Diagnosis of Spinal Stenosis, Osteophytes, and Ligament Ossification

Clinical Examination and Imaging

The diagnostic process for spinal stenosis begins with a thorough neurological and orthopedic examination by a physician. This includes assessing motor strength, sensation, reflexes, gait, and spinal range of motion. Based on these findings, imaging studies are typically ordered:

- Plain Radiographs (X-rays) of the Spine (Spondylograms): Can reveal indirect signs suggestive of spinal canal stenosis, such as enlarged articular processes (facet hypertrophy), thickened laminae, reduced vertebral body height, sclerosis (hardening) of ligaments, and osteophytes. Dynamic views (flexion/extension) can assess for instability.

- Myelography (Historical/Adjunctive): Involves injecting contrast dye into the spinal canal followed by X-rays or CT. It can demonstrate uniform or multilevel constriction (narrowing) of the spinal canal. Less common now with advanced MRI.

- Computed Tomography (CT) of the Spine: Provides excellent detail of bony structures, allowing precise measurement of spinal canal dimensions and visualization of osteophytes, facet hypertrophy, and ligamentum flavum thickening. Cross-sectional imaging at the level of suspected stenosis is crucial for differential diagnosis and assessing the degree of narrowing.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Spine: The gold standard for diagnosing spinal stenosis and its effects on neural structures. MRI clearly shows the spinal cord, nerve roots, intervertebral discs (protrusions, herniations), ligaments (hypertrophy, ossification), and the degree of canal compromise. It can also detect signal changes within the spinal cord indicative of myelopathy.

Educational video: A CT scan of the spine is a valuable tool that may be utilized to evaluate a range of spinal conditions, including herniated discs, spinal stenosis, scoliosis, traumatic spinal injuries, tumors, congenital spinal anomalies such as spina bifida, as well as vascular abnormalities or infections affecting the spine.

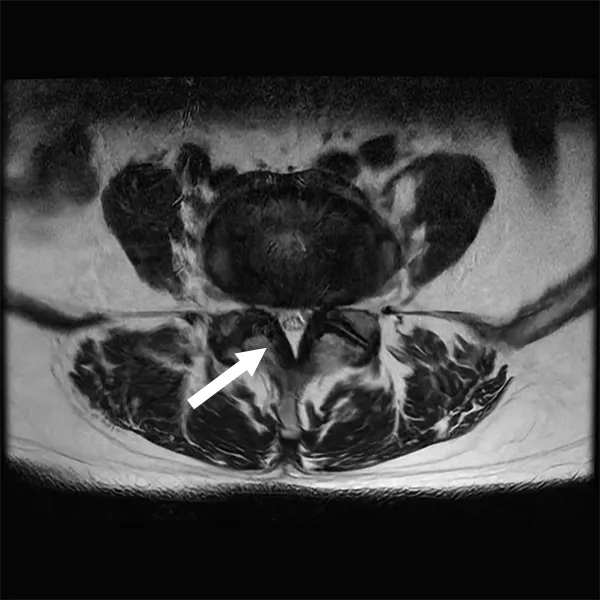

The clinical presentation of spinal canal stenosis can range from monoradicular symptoms (affecting a single nerve root), often associated with intervertebral disc protrusions/herniations or hypertrophy of adjacent articular processes causing foraminal narrowing, to more severe symptoms of compression-ischemic myeloradiculopathy (damage to both spinal cord and nerve roots due to pressure and reduced blood flow). In rare instances, a transverse myelopathy syndrome (affecting a cross-section of the spinal cord) may occur.

The primary symptoms of spinal canal stenosis often include persistent lumbar spine pain, which may or may not radiate along the distribution of nerve roots. This lumbar pain is frequently persistent and may not be alleviated by changes in position; in some instances, it can even worsen when lying supine (on the back). As the disease progresses, patients may develop a loss of lumbar lordosis (flattening of the natural inward curve of the lower back), scoliosis (sideways curvature), muscle contractures, and antalgic (pain-avoiding) spinal deformities.

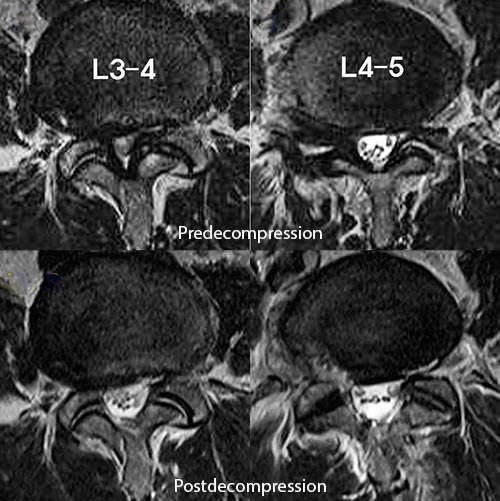

Sagittal MRI scan revealing spinal canal stenosis at the L4-L5 vertebral level.

Axial MRI scan demonstrating bilateral lateral recess stenosis at the L4-L5 level.

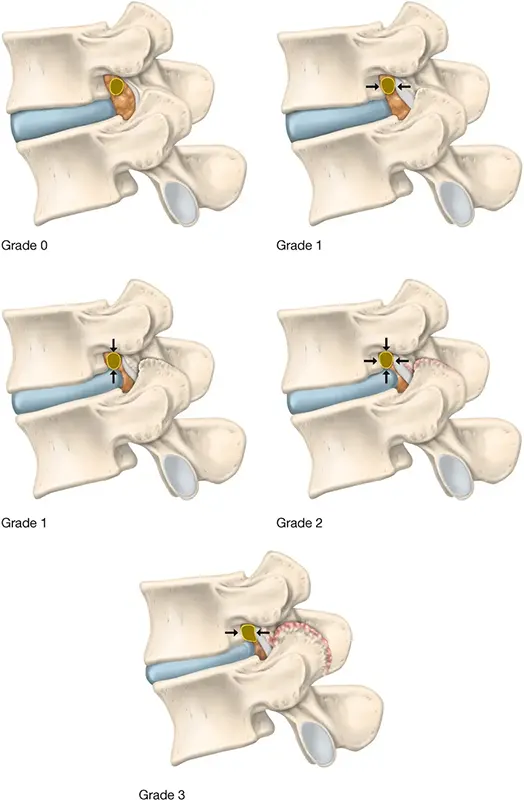

Radiological Grading of Foraminal Stenosis

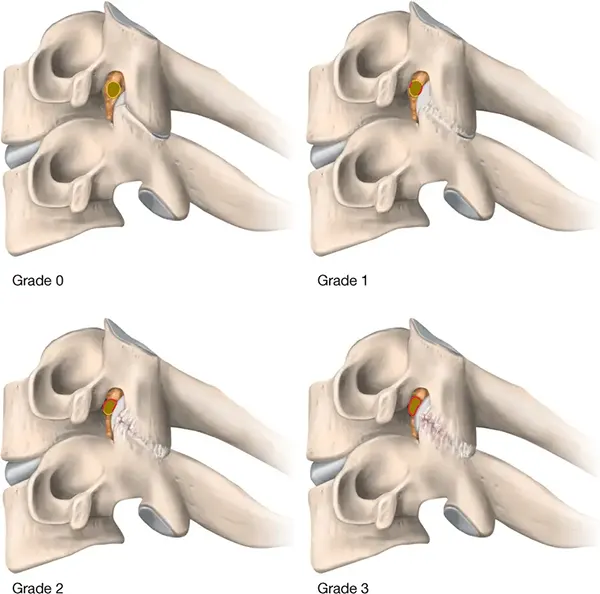

Foraminal stenosis refers to the narrowing of the intervertebral foramen, the opening in the spinal vertebrae through which nerve roots exit the spinal canal. Radiological methods, such as MRI or CT, are commonly used to investigate foraminal stenosis in patients presenting with radicular pain in the extremities. Imaging is required to confirm the diagnosis and grade its severity. Several grading systems based on MRI findings exist:

Schematic illustration of the Park system for grading cervical foraminal stenosis based on oblique sagittal MRI findings.

Park system for cervical foraminal stenosis based on oblique sagittal MRI:

| Grade | MRI Presentation |

|---|---|

| No foraminal stenosis and no perineural fat obliteration. | |

| Grade 1 | Mild foraminal stenosis with < 50% perineural fat obliteration around the nerve root. |

| Grade 2 | Moderate foraminal stenosis with > 50% perineural fat obliteration, but no morphological change (compression or collapse) of the nerve root. |

| Grade 3 | Severe foraminal stenosis with morphologically collapsed or compressed nerve root and severe perineural fat obliteration. |

Schematic illustration of the Lee system for grading lumbar foraminal stenosis based on sagittal MRI findings.

Lee system for lumbar foraminal stenosis based on sagittal MRI:

| Grade | MRI Presentation |

|---|---|

| No lumbar foraminal stenosis or perineural fat obliteration. | |

| Grade 1 (Mild) | Mild foraminal stenosis with perineural fat obliteration in one direction (transverse or vertical narrowing). |

| Grade 2 (Moderate) | Moderate foraminal stenosis with complete perineural fat obliteration (surrounding foraminal narrowing from all directions), but no morphological change (compression or collapse) to the nerve root. |

| Grade 3 (Severe) | Severe foraminal stenosis with total perineural fat obliteration and a morphological collapse or compression of the exiting nerve root. |

Treatment of Spinal Stenosis, Osteophytes, and Ligament Ossification

Treatment options for spinal canal stenosis vary depending on the severity of symptoms, the underlying causes (such as osteophytes or ligament ossification), the location of the stenosis, and the patient's overall health. The primary goals are to relieve pain, improve function, and prevent neurological deterioration.

Conservative Management

First-line therapy for many patients, especially those with mild to moderate symptoms, involves conservative measures:

- Activity Modification: Avoiding activities that exacerbate symptoms (e.g., prolonged standing or walking for lumbar stenosis, certain neck movements for cervical stenosis).

- Pharmacological Treatments:

- Drug therapy: Including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce pain and inflammation, analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen), and sometimes muscle relaxants. For neuropathic pain, medications like gabapentin or pregabalin may be prescribed. Hormones (oral corticosteroids) may be used for short periods during acute flare-ups.

- Physical Therapy (Physiotherapy): A crucial component, focusing on:

- Exercises to improve strength (especially core muscles), flexibility, and posture.

- Flexion-based exercises for lumbar stenosis can often provide relief.

- Modalities such as heat/cold therapy, ultrasound, or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

- Manual Therapy: May include muscle, articular (joint), and radicular (nerve) techniques to improve mobility and reduce pain.

- Alternative Therapies: Acupuncture may provide symptomatic relief for some patients.

- Bracing: Lumbar corsets or cervical collars may offer temporary support and pain relief but are generally not recommended for long-term use as they can lead to muscle deconditioning.

Interventional Pain Management

- Therapeutic Injections: Epidural steroid injections can deliver anti-inflammatory medication directly to the area of nerve compression, providing temporary to moderate-term pain relief. Facet joint injections or medial branch blocks may be used if facet arthropathy is a significant pain contributor. However, long-term benefits from epidural steroid injections for spinal stenosis have not been definitively established.

Surgical Treatment Options

Surgical treatment is typically considered for patients with persistent, disabling pain, progressive neurological deficits (e.g., worsening weakness, myelopathy), or significant activity limitation despite an adequate trial of conservative management. The goal of surgery is to decompress the neural elements (spinal cord or nerve roots).

Several surgical techniques are available, with a growing focus on minimally invasive approaches:

Minimally Invasive Lumbar Decompression (MILD)

This procedure, often abbreviated as MILD®, is specifically designed to treat lumbar spinal stenosis caused by hypertrophy (thickening) of the ligamentum flavum. It is performed under local anesthetic with sedation, allowing patients to remain awake. Using small incisions and specialized tools guided by fluoroscopy, a portion of the thickened ligamentum flavum is removed, creating more space in the spinal canal. While it can be effective for central canal stenosis primarily due to ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, its success rate is reported to be around 50% in some studies, and it may not adequately address lateral recess or foraminal stenosis caused by other factors like facet hypertrophy or disc herniation.

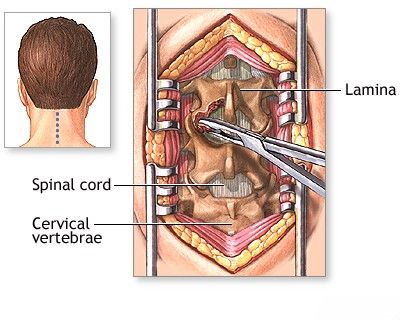

Laminectomy and Fusion

A traditional surgical approach, laminectomy involves the removal of the lamina (the posterior part of a vertebra) to widen the spinal canal and relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots. In cases where spinal instability is present or may be created by the decompression (e.g., with degenerative spondylolisthesis), laminectomy is often combined with spinal fusion. Fusion uses bone grafts and often instrumentation (screws, rods, cages) to permanently join two or more vertebrae, stabilizing the spine. While effective for decompression and stabilization, this method typically requires a longer recovery period and can place additional stress on adjacent spinal segments, potentially accelerating degeneration at those levels over time (adjacent segment disease).

Foraminotomy

This surgical procedure specifically targets foraminal stenosis by enlarging the intervertebral foramen (the opening where nerve roots exit). The surgeon removes bone, tissue, or other structures (such as osteophytes or herniated disc material) that are compressing the nerve root. Foraminotomy can be performed as a standalone procedure or in conjunction with a laminectomy or discectomy. It is often done using minimally invasive techniques with an endoscope or microscope for precision, leading to smaller incisions and potentially faster recovery compared to more extensive open surgeries. It is primarily aimed at relieving radicular pain.

Posterior Interspinous Spacing/Fusion Devices

These techniques utilize implants placed between the spinous processes of adjacent vertebrae. The aim is to distract the spinous processes, which indirectly widens the spinal canal and foramina by reducing ligamentum flavum buckling and opening the posterior disc space. This can decompress the nerves and alleviate symptoms of neurogenic claudication. These devices can potentially address central, lateral recess, and foraminal stenosis. Several specialized devices are available, often inserted via minimally invasive approaches:

- Minuteman®: A minimally invasive implant typically inserted through a lateral (side) approach with a small incision. It is designed to provide stabilization while potentially preserving some segmental motion, although it often promotes fusion.

- Zip®: A device that attaches to the spinous processes after a small posterior incision, "zipping" into place to hold the vertebrae apart and provide stability, often intended for fusion. Variants like the Zip 51 are engineered for specific spinal levels, such as the L5-S1 junction, which is prone to degeneration.

- Flow Spine (and similar expandable spacers): Newer generation devices, some of which are expandable and may be deployed to exert distractive forces. Some designs aim to distribute forces more evenly and reduce stress on the spinous processes compared to traditional spacers.

Staged Surgical Approaches

In certain complex cases of spinal stenosis, particularly with multilevel involvement or significant comorbidities, a staged surgical approach might be considered. For example, the first stage could involve a more limited decompression of the most symptomatic nerve roots or spinal cord levels. This might be followed by a course of intensive vasoactive (to improve blood flow) and neurostimulatory therapy. If the patient's condition does not show satisfactory improvement, a second stage of surgery, potentially involving a wider decompression (e.g., bilateral hemilaminectomy) and creation of additional reserve spaces, could be proposed. This approach aims to balance the extent of surgery with the patient's tolerance and response.

When surgical indications for spinal stenosis are present, the extent of the stenosis should guide the choice of procedure. For stenosis affecting one or two vertebral levels with unilateral radicular symptoms, interlaminotomy (removal of a small portion of adjacent laminae) or hemilaminectomy (removal of lamina on one side) are appropriate options. These are typically considered when conservative treatments fail and imaging confirms stenosis correlating with the neurological deficit. For bilateral symptoms of neurovascular compression in multilevel spinal stenosis, a bilateral hemilaminectomy might be performed, often preserving the spinous processes and interspinous ligament, and including excision of the hypertrophied ligamentum flavum and osteophytes. Concurrent foraminotomies are advisable if significant foraminal stenosis coexists. In certain cases, particularly with associated instability, spinal stabilization with metal instrumentation may be required in conjunction with decompression.

A posterior hemilaminectomy is a surgical procedure performed to address cervical spinal stenosis with associated spinal cord compression, often caused by hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum, as confirmed by imaging. The goal of this procedure is to decompress the spinal cord.

This MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrates spinal stenosis before treatment and shows evidence of prior endoscopic decompression performed at the L3-L4 and L4-L5 vertebral levels, aiming to alleviate neural compression.

Lumbar spinal stenosis is a significant condition, affecting approximately 103 million people worldwide and around 11% of older adults in the US. As highlighted, initial management often involves activity modification, analgesia, and physical therapy. Selected patients with persistent pain and activity limitation may become candidates for decompressive surgery.

Differential Diagnosis of Spinal Stenosis Symptoms

Symptoms of spinal stenosis, particularly neurogenic claudication and radiculopathy, can mimic other conditions:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Spinal Stenosis (Neurogenic Claudication) | Leg/buttock pain, numbness, weakness provoked by walking/standing, relieved by sitting/flexion. Neurological signs may be present. Imaging confirms canal narrowing. |

| Vascular Claudication (Peripheral Arterial Disease) | Cramping leg pain with exertion, relieved by rest (regardless of posture). Diminished peripheral pulses, skin changes. Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) reduced. Bicycling often still provokes pain. |

| Herniated Intervertebral Disc (Acute Radiculopathy) | Often acute onset of dermatomal pain, numbness, weakness. Positive nerve tension signs (e.g., straight leg raise). MRI confirms disc herniation. |

| Hip Osteoarthritis | Groin/buttock/thigh pain, worse with activity, limited hip range of motion. Pain often localized to hip joint. X-ray/MRI of hip shows arthritis. |

| Peripheral Neuropathy (e.g., Diabetic) | Numbness, tingling, burning pain, weakness, often in a "glove and stocking" distribution. Reflexes may be diminished. Not typically posture-dependent. EMG/NCS abnormal. |

| Spinal Tumors or Infections (Spondylitis) | Persistent pain, often worse at night, constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss). Rapidly progressive neurological deficits. Imaging and biopsy are key. |

Potential Complications of Spinal Stenosis

If left untreated or if it progresses, spinal stenosis can lead to:

- Chronic, debilitating pain.

- Progressive weakness and numbness in the extremities.

- Difficulty with walking and balance, increasing fall risk.

- Loss of fine motor skills (with cervical stenosis).

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction (e.g., incontinence, retention - signs of severe compression like cauda equina syndrome or advanced myelopathy).

- Permanent nerve damage.

- Reduced quality of life and independence.

Prevention and Lifestyle Considerations

While degenerative spinal stenosis is largely related to aging, certain lifestyle factors may help manage symptoms or potentially slow progression:

- Regular Exercise: Maintaining core strength, flexibility, and overall fitness. Low-impact exercises are often preferred.

- Weight Management: Reducing excess body weight decreases stress on the spine.

- Good Posture: Maintaining proper posture during daily activities.

- Ergonomics: Using ergonomic principles at work and home.

- Avoiding Smoking: Smoking can accelerate disc degeneration.

When to Consult a Spine Specialist

Individuals should consult a spine specialist (e.g., orthopedic spine surgeon, neurosurgeon, physiatrist) if they experience:

- Persistent pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness in the neck, back, arms, or legs.

- Symptoms of neurogenic claudication (leg pain with walking/standing, relieved by rest/flexion).

- Difficulty with balance or coordination.

- Loss of fine motor skills in the hands.

- New onset or worsening bowel or bladder dysfunction (this is a medical emergency).

- Symptoms that significantly limit daily activities or quality of life despite conservative measures.

Early diagnosis and appropriate management can help alleviate symptoms, improve function, and prevent irreversible neurological damage.

References

- Katz JN, Harris MB. Clinical practice. Lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008 Feb 21;358(8):818-25.

- Genevay S, Atlas SJ. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010 Apr;24(2):253-65.

- Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Riew KD, et al. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients With Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Recommendations for Patients With Mild, Moderate, and Severe Disease and Nonmyelopathic Patients With Evidence of Cord Compression. Global Spine J. 2017 Sep;7(3 Suppl):70S-83S.

- Lee SY, Kim TH, Oh JK, Lee SJ, Park MS. Lumbar Stenosis: A Recent Update by Review of Literature. Asian Spine J. 2015 Oct;9(5):818-28.

- Park JB, Lee JK, Park SJ, Riew KD. The oblique sagittal view of MRI for the diagnosis of cervical foraminal stenosis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2013 Jun;26(4):191-6. (Reference for Park classification)

- Lee S, Lee JW, Yeom JS, et al. A practical MRI grading system for lumbar foraminal stenosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010 Sep;195(3):717-21. (Reference for Lee classification)

- Deer TR, Grider JS, Lamer TJ, et al. A Systematic Literature Review of Spine Neurostimulation Therapies for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Pain Med. 2020 Nov 7;21(7):1590-1603. (Broader context, some patients may have coexisting conditions)

- Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008 Feb 21;358(8):794-810.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome