Spinal pain in the lumbar region (lower back)

- Understanding Spinal Pain in the Lumbar Region (Low Back Pain)

- Clinical Presentation and Patient Assessment

- Diagnosis of Lumbar Spine Pain

- Treatment of Lumbar Spine Pain

- Sciatica: Symptoms, Causes, and Duration (Table Summary)

- Differential Diagnosis of Low Back Pain

- Prevention and Lifestyle Considerations

- When to Seek Medical Attention

- References

Understanding Spinal Pain in the Lumbar Region (Low Back Pain)

Pain in the lumbar spine, commonly referred to as low back pain, is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal complaints among adults worldwide. Its occurrence is frequently linked to an individual's lifestyle, occupational demands, physical fitness level, and history of previous trauma or injury. Understanding the different types and origins of low back pain is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

Types of Low Back Pain

Patients presenting with low back pain most often describe one or a combination of the following four types of pain:

- Local Pain: Pain felt directly at or near the site of the underlying pathology in the lumbar spine.

- Referred Pain: Pain perceived in a region distant from its actual source, but within the same or adjacent segmental innervation.

- Radicular Pain: Pain that radiates along the course of a spinal nerve root, typically caused by compression or irritation of that nerve root.

- Muscle Pain (Myofascial Pain): Pain originating from muscles and their surrounding connective tissue (fascia), often resulting from secondary (protective) muscle spasm, trigger points, or conditions like fibromyalgia.

Local Pain

Local pain in the lower back can be associated with any pathological process that affects or irritates pain receptors (nociceptors) located in various spinal structures. It's important to note that involvement in a pathological process of structures that do not contain sensitive nerve endings (like the central, trabecular part of a vertebral body containing red bone marrow) may initially be painless. For instance, the central part of a vertebral body can be significantly destroyed by a tumor or hemangioma without causing pain until the process extends to pain-sensitive structures.

However, damage or inflammation involving the cortical layer of the vertebra, the periosteum (the membrane covering bones), synovial membranes of the intervertebral (facet) joints, paraspinal muscles, the fibrous outer ring (annulus fibrosus) of intervertebral discs, or spinal ligaments are often extremely painful for the patient. Although these painful conditions are frequently accompanied by edema (swelling) of the affected tissues, this swelling may not be visibly apparent if the pathological process is located deep to the skin of the lower back.

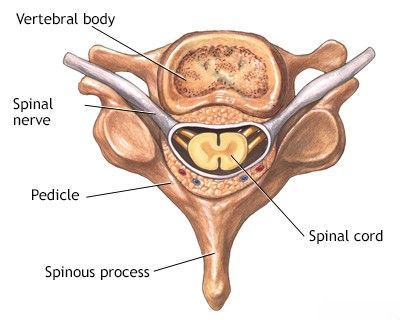

This cross-sectional view shows the intricate structure of the spine and spinal cord, where local pain can arise from various components like vertebral bodies, discs, joints, or surrounding soft tissues.

Local back pain is often persistent. Its intensity can fluctuate depending on changes in body position or movement. The pain may be described as sharp, stabbing, aching, or dull. It is typically felt in the affected part of the back but can sometimes be diffuse or radiate slightly away from the primary site. Movements or changes in body position (such as tilting, bending, or getting out of bed) that displace or stress damaged and inflamed tissues often exacerbate local pain. Strong pressure or percussion (tapping) over the surface of the lower back during a physical examination can also elicit soreness, which helps in localizing the site of injury or inflammation.

Referred Pain

Referred pain in the lower back context can be of two main types:

- Pain that originates from pathological processes in the spine (vertebrae, discs, ligaments, facet joints) and radiates (is referred) to areas lying within the dermatomal or sclerotomal zones of the lumbar and upper sacral segments of sensory innervation.

- Pain that originates from diseases of visceral (internal) organs (e.g., pelvic organs, abdominal organs like kidneys or pancreas) and is referred to the spine (back).

Referred pain originating from diseases of the upper lumbar spine (e.g., L1-L3) typically radiates to the anterior (front) surfaces of the thighs and lower legs. Referred pain resulting from damage to the lower lumbar (L4-L5) and sacral spinal structures commonly radiates to the buttocks, the posterior (back) surfaces of the thighs and lower legs, and can sometimes reach the feet. This type of referred pain, although its source is located deep within the spinal structures, is often perceived by the patient as prolonged, dull, aching, not acutely sharp, and relatively diffuse. It can frequently be felt by the patient as if it is on the surface of the skin or in superficial tissues.

The strength and intensity of referred pain can be similar to that of local back pain. Factors that alter local pain (e.g., mechanical load, specific movements) similarly affect referred pain, although this effect might not be as pronounced or as clearly linked as with radicular pain. It is important to differentiate referred pain from spinal origin from pain referred to the back from visceral diseases. With diseases of internal organs, patients usually describe the pain as deep, pulling, or cramping, often radiating from the abdomen or pelvis to the back. Visceral referred pain is typically not affected by spinal movements, does not decrease significantly in the supine position, and may change in intensity related to the activity of the involved internal organ (e.g., intestinal peristalsis, urination, menstruation).

Radicular Pain

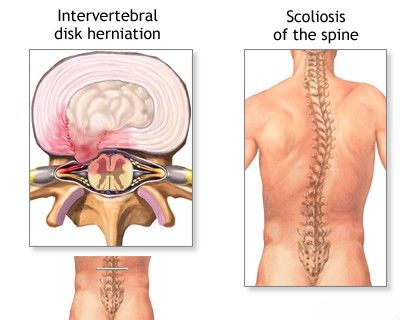

Radicular pain, often referred to as nerve root pain or sciatica when involving the sciatic nerve, occurs when spinal nerve roots in the lower back are affected (compressed, irritated, or inflamed). While radicular pain is a type of referred pain (as it is felt distant from the nerve root itself), it has distinct characteristics. It is typically more intense, often described as sharp, shooting, "electric shock-like," or lancinating, and it radiates from the spine down into the limb along the specific dermatomal distribution of the affected nerve root. The conditions causing radicular pain usually involve mechanical stretching, irritation, or compression of the spinal nerve root, most commonly within the spinal canal or intervertebral foramen (e.g., by a herniated intervertebral disc, spinal stenosis, or osteophytes).

Pain along the course of the nerve root can also be aching, prolonged, dull, and not excessively intense, especially in chronic compression. However, with various influences that increase the degree of nerve root compression or irritation (e.g., certain movements, coughing, sneezing), the pain can significantly intensify, becoming piercing or cutting in quality.

Compression of the sciatic nerve, often due to a herniated disc in the context of lumbar osteochondrosis, leads to the characteristic radiating leg pain known as sciatica.

Radicular pain can spread from the back (lumbar spine) to any area of the leg, including the buttock, thigh, area under the knee, lower leg (shin), or foot and toes, depending on the specific nerve root involved (e.g., L4, L5, S1). Maneuvers that increase intraspinal pressure, such as coughing, sneezing, or straining (Valsalva maneuver), can exacerbate radicular pain, similar to their effect on local pain from disc herniation. Movements that cause stretching of the affected nerve root (e.g., forward bending with straight legs, straight leg raise test - Lasegue's sign) will typically increase radicular pain. Clamping the jugular veins in the neck (Queckenstedt's test - historical, rarely used now) can increase cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure, potentially causing displacement of the nerve root or increased pressure on it, thereby increasing radicular pain.

Irritation or compression of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots, which contribute to the sciatic nerve, typically causes pain radiating down the posterior or posterolateral surface of the thigh, posterolateral or anterolateral surfaces of the lower leg, and into the foot. This specific type of radicular pain along the sciatic nerve is termed sciatica. Paresthesias (spontaneous unpleasant sensations like numbness, tingling, or burning), decreased skin sensitivity (hypoesthesia), skin soreness, and tenderness along the nerve usually accompany pain related to involvement of the posterior (sensory) fibers of the spinal nerve root. If the motor fibers of the anterior root of the spinal nerve are involved in the pathological process, then loss of deep tendon reflexes (e.g., knee jerk for L4, ankle jerk for S1), muscle weakness, muscle atrophy, and fasciculations (convulsive, involuntary twitching of individual bundles of muscle fibers) may occur. Occasionally, venous edema in the affected limb can be noted.

Muscle Pain (Myofascial Pain Syndrome, Fibromyalgia)

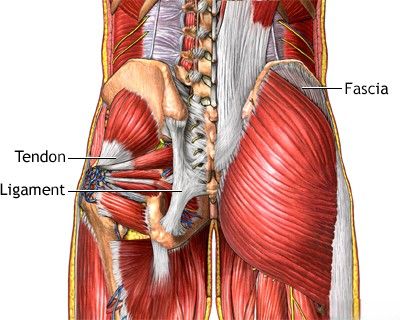

Muscle pain, often presenting as myofascial pain syndrome or contributing to the widespread pain of fibromyalgia, is a very common type of pain in the lower back that occurs with acute or chronic muscle spasm and tension. Muscle spasm is often a secondary, protective response to underlying spinal pathology (e.g., disc herniation, facet joint arthritis, spinal instability) or direct muscle strain, causing significant disturbances in the patient's normal posture and movement. Chronic muscle tension is perceived by the patient as an aching, sometimes cramping, pain. During physical examination, palpation of the muscles of the lower back often reveals tension and tenderness in the sacrospinalis (erector spinae) and gluteal muscles. Specific tender points or trigger points within these muscles may be identified, which, when pressed, reproduce the patient's pain, sometimes with a characteristic referral pattern.

This illustration highlights the localization of typical painful trigger points associated with fibromyalgia (muscle pain) or myofascial pain syndrome, which can be a significant source of low back pain.

Common Causes and Contributing Factors

Low back pain is a symptom with numerous potential underlying causes. These can range from acute injuries to chronic degenerative processes and, less commonly, systemic diseases or congenital abnormalities.

Factors often contributing to low back pain include:

- Lifestyle Factors:

- Prolonged sitting (e.g., sedentary work at a computer, long-distance driving).

- Poor posture during daily activities.

- Lack of regular physical activity and deconditioning of core muscles.

- Obesity, which places increased stress on the spine.

- Smoking, which can impair disc nutrition and healing.

- Acute or Chronic Overload/Strain:

- Improper lifting techniques or lifting excessive weights.

- Sudden awkward movements or twists.

- Overuse or repetitive strain during sports or physical labor (e.g., back pain during pregnancy from carrying a child, or when caring for individuals with limited mobility).

- Chronic overstrain of back muscles due to prolonged uncomfortable positions.

- Trauma:

- Spinal fractures (e.g., compression fractures due to osteoporosis or significant trauma).

- Whiplash-type injuries (though more common in the neck, can affect the entire spine).

- Degenerative Processes (often age-related):

- Osteochondrosis (degenerative disc disease), leading to decreased disc height and altered biomechanics.

- Intervertebral disc protrusion or herniation (extrusion), which can compress nerve roots.

- Spondylosis (formation of osteophytes or bone spurs).

- Spondyloarthrosis (osteoarthritis of the facet joints).

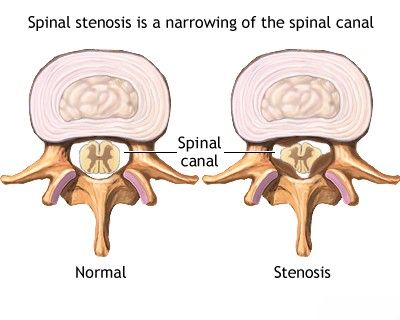

- Spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal or neural foramina).

- Spondylolisthesis (degenerative or isthmic vertebral slippage).

- Inflammatory Conditions:

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint), as seen in ankylosing spondylitis or other spondyloarthropathies.

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint.

- Discitis (infection of an intervertebral disc).

- Congenital Spinal Abnormalities: Such as spina bifida, lumbarization, or sacralization, which can alter spinal mechanics and predispose to pain.

- Systemic Diseases: Less commonly, osteoporosis, infections (e.g., spondylitis), tumors (primary or metastatic), or rheumatological conditions can cause low back pain.

- Psychosocial Factors: Stress, depression, anxiety, and job dissatisfaction can influence the perception and persistence of low back pain.

Often, a specific cause for an episode of low back pain cannot be definitively identified, and it is termed "non-specific low back pain." This is frequently related to musculoskeletal strains or sprains.

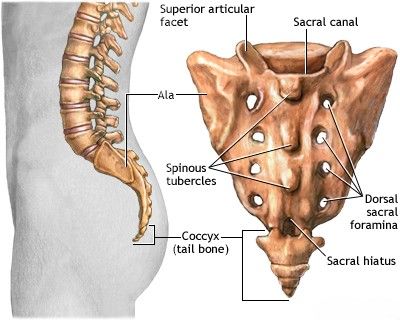

Inflammation of the articular surfaces of the sacroiliac joint (sacroiliitis) is a common cause of pain in the lower back and sacrum (sacrodynia).

In outpatient practice, particularly in patients with osteochondrosis of the spine, an accumulative or cumulative mechanism for the occurrence of back pain is frequently observed. Problems often accumulate over time in the neck and lower back. The appearance of a fairly persistent pain symptom is often preceded by a long period of discomfort or minor aches before an acute exacerbation of the disease occurs.

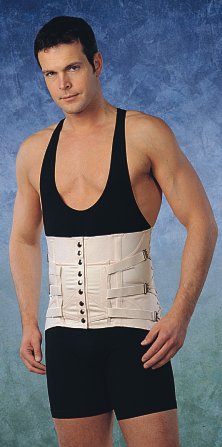

Such patients often endure unpleasant sensations and back pain intermittently for months or even years. To relieve pain and eliminate discomfort during movement or at rest, they frequently resort to various anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications, rubs, gels, and ointments. For back pain, supportive bandages and corsets, as well as various types of massagers and applicators, are also commonly used.

The symptom of back pain is notably less common in individuals who maintain an active and sporty lifestyle. Prevention of the development of degenerative disc disease and the onset of pain symptoms is primarily promoted by regular independent gymnastics and active recreation. Gymnastics helps to relieve the daily cumulative load on the same muscles, ligaments, and joints of the lumbar spine, promoting better spinal health.

Clinical Presentation and Patient Assessment

Nature of Pain and Aggravating Factors

A patient with chronic low back pain is often unable to precisely pinpoint its exact origin or describe it clearly. Sensations like muscle tension, convulsive twitching (fasciculations), tearing or throbbing pain in the shins, or feelings of burning, coldness, paresthesia (tingling), and numbness are characteristic of diseases affecting the spinal nerves or their sensory roots (neuropathy or radiculopathy).

After the patient has described the nature and location of their pain, the doctor aims to determine factors that aggravate or alleviate this pain. During the interview, the duration of the pain is specified, its dependence on body position (e.g., increased when lying, sitting, or standing), and the influence of trunk movements (e.g., bending forward), coughing, sneezing, and straining (Valsalva maneuver). The exact moment of pain onset and the circumstances that caused it can have significant diagnostic value. Given that many lower back diseases are the result of injuries sustained during work activities or accidents, it is necessary to consider the possibility of exaggeration of the patient's condition for reasons of compensation or other personal motives, as well as the influence of hysterical neurosis or malingering, though these are less common.

Physical Examination Findings

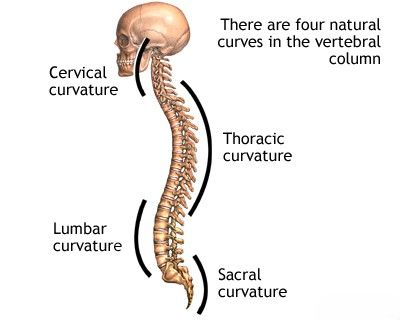

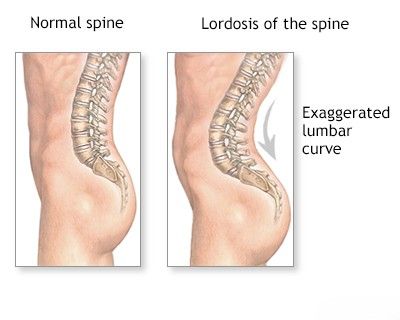

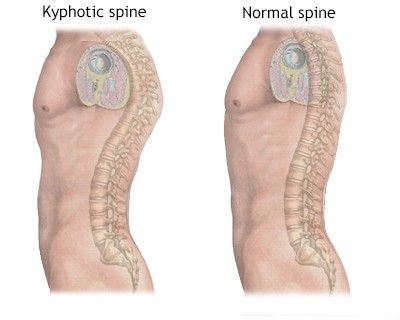

A normal examination of a healthy spine reveals natural curves: thoracic kyphosis (outward curve) and lumbar lordosis (inward curve). In some individuals, these curvatures can be exaggerated, leading to a "round back" or hyperlordosis. In spinal diseases, any excessive curvature or, conversely, a flattening or loss of normal lumbar lordosis is carefully assessed. A kyphotic hump (an acute angular kyphosis) can result from a vertebral fracture, a congenital spinal abnormality, an abnormal pelvic tilt, or an imbalance in the tone of paravertebral or gluteal muscles. In cases of acute pain along an inflamed sciatic nerve (sciatica), a forced, protective posture of the lower back (antalgic scoliosis or list) may be observed, which slightly reduces the severity of pain from nerve tension.

Questioning a patient about old injuries does not always help identify the causes of current low back pain. Clarification of the time of onset and the specific circumstances surrounding the onset of pain often provides the neurologist or neurosurgeon with much more valuable information necessary for making an accurate diagnosis.

During the physical examination, the patient's biomechanics are also studied. The spine, hip joints, and legs are assessed as the patient performs certain active movements. Limitations in movement may be noted when the patient is undressing, lying down, or getting up from the examination couch or chair. When the trunk is tilted forward from a standing position, normal lumbar lordosis typically flattens or even reverses slightly, and the curvature of the thoracic spine (thoracic kyphosis) increases. In conditions causing back pain, such as when posterior ligaments or sacrospinalis muscles are tense, when the articular surfaces of the intervertebral joints are inflamed, or with ruptures of intervertebral discs in the lumbar spine, protective reflexes prevent stretching of these spinal structures. As a result, the sacrospinalis muscles remain tense and restrict movement in the lumbar spine. Forward flexion during low back pain will then occur primarily at the hip joints and the thoracolumbar junction. With inflammation of the lumbosacral joints (sacroiliitis) and compression of spinal nerve roots, the patient may lean forward to avoid tension in the hamstring muscles, shifting the main load to the pelvis. With unilateral sciatica, the spinal curvature (antalgic list) will often be directed away from the source of low back pain to decompress the nerve root. Movements in the patient's lower back will be accompanied by muscle tension and soreness. The patient will try to tilt the torso forward primarily using the hip joints. The knee on the affected side may be bent to relieve hamstring spasm, while the pelvis is tilted posteriorly to reduce tension on the spinal nerve root and the sciatic nerve in general.

If the patient's ligaments or muscles are tense, performing a lateral tilt (side bending) in the opposite direction will increase the pain due to stretching of these soft tissues of the spine. With lateral and paramedian hernias and protrusions of intervertebral discs, inclination towards the side of the injury will be impossible or severely limited due to increased pain. For pain in the lower back, flexion in a sitting position with bent hip joints and knees can usually be performed easily until the knees come into contact with the chest. This is because flexion of the knees relieves tension in the patient's hamstrings and also reduces tension on the sciatic nerve.

For low back pain and sciatica, passive flexion of the lower back in the supine position (e.g., bringing knees to chest) may cause mild pain. If the patient's knees are bent (thus reducing sciatic nerve tension), the movement often occurs more freely. With diseases of the lumbosacral and lumbar spine (for example, with arthritis of the facet joints), passive flexion of the hip joints occurs freely or with minor pulling pain in the lower back due to stretching of the gluteal muscles. Passive lifting of a straight leg (Straight Leg Raise test or Lasegue's sign), which in most healthy people occurs without pain up to 80-90 degrees (except for those with poor hamstring flexibility), leads to tension on the sciatic nerve and its roots, causing or exacerbating pain if radiculopathy is present. Low back pain can also occur when the pelvis rotates around its transverse axis, as this movement increases the load on the joints of the lumbosacral spine. With arthritis or arthrosis of these joints, the patient will complain of pain during this movement. In diseases of the intervertebral joints of the lumbosacral spine and compression of the spinal nerve roots, this rotational movement is often limited on the side of the lesion compared to the opposite side of the body.

The Lasegue's sign (pain and limited range of motion when the hip is flexed with the knee extended) can help diagnose nerve root irritation contributing to low back pain. Raising a straightened leg on the side opposite to the lesion (Crossed Straight Leg Raise or Fajersztajn's sign) can also cause localized pain on the affected side. This contralateral pain, if present, may be a sign of a more significant intervertebral disc lesion, such as a large central herniation or extrusion, rather than just a simple protrusion. The pain caused by this test in the patient will typically radiate to the affected side of the lower back, regardless of which leg was raised.

Backward bending of the body (extension) is most easily performed when a patient is standing or lying on their stomach. With an exacerbation of a condition like acute disc herniation, it may be difficult for the patient to straighten the spine from a flexed position. However, a person with simple muscular tension in the lower back or with some types of disc protrusions can usually straighten or bend the spine backward without a significant increase in pain. If the damage is localized in the upper lumbar segments of the spine, or if there is an active inflammatory process (spondylitis) or a fracture (crack) of a vertebral body or posterior vertebral structures (e.g., facet joints, pars interarticularis), then backward bending can be significantly difficult or painful due to increasing compressive loads on these structures.

Inflammation of the sacroiliac joint (sacroiliitis) in its acute stage is a common cause of pain localized to the sacrum (sacrodynia) and lower back.

Palpation and percussion (tapping) in the projection of the spine are typically carried out at the end of the physical examination. It is advisable to begin palpation in an area that is initially unlikely to be a source of pain, allowing the patient to relax tense back muscles without fear of increased pain during the examination by a neurologist or neurosurgeon. The examining physician should always be aware of which spinal structures are accessible to palpation in the lower back. Localized pain upon finger pressure in the lumbar region is rarely specific to a deep spinal disease without other signs. The deep structures of the spine in the lumbar region are often located too far from the surface to elicit distinct soreness on superficial palpation alone, unless inflammation is severe or very superficial. Mild or poorly localized pain on palpation of the lower back may only indicate a pathological process within the affected spinal segment that refers pain to the overlying skin in the dermatomal zone of the involved nerve.

Pain with pressure in the projection of the costovertebral angle (junction of the 12th rib and spine) can be indicative of kidney disease (e.g., pyelonephritis), adrenal gland issues, or damage to the transverse processes of the L1 or L2 vertebrae. Increased sensitivity to palpation of the transverse processes of the remaining lumbar vertebrae and the sacrospinalis muscles passing over them may suggest a fracture of a transverse process or muscle tension at their points of attachment to the spine. Pain on palpation of a spinous process or increased pain due to tapping on it is a nonspecific symptom but can suggest underlying pathology such as damage to the central part of an intervertebral disc, inflammation (discitis), or a fracture. Pain from pressure in the projection of the articular surfaces between the L5 and S1 vertebrae (L5-S1 facet joints) can occur when these joints or the intervertebral disc at this level are affected. Pain in this area is also commonly found in inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or other spondyloarthropathies affecting these joints.

During palpation of the spinous processes, a neurologist or neurosurgeon notes any deviation from the central midline (laterally) or in the anteroposterior plane (step-offs), as this may indicate a fracture, facet joint arthritis with instability, or spondylolisthesis (anterior displacement of a vertebra relative to the one below). If a spinous process appears to "sink" or is displaced forward relative to adjacent ones, it may suggest spinal instability with anterolisthesis.

Examination of the abdominal cavity, rectum, and pelvic organs, along with an assessment of the condition of peripheral vessels in the legs, are also important components of evaluating a patient with complaints of low back pain. These should not be neglected, as they can help identify or rule out diseases of blood vessels, internal organs, or the presence of tumors or inflammation that could either extend to the spine or cause pain that is referred to the lumbar region.

Diagnosis of Lumbar Spine Pain

Neurological and Orthopedic Examination

The diagnostic process begins with a comprehensive neurological and orthopedic examination. This assesses the patient's neurological status (motor strength, sensation, reflexes) and identifies possible violations in the biomechanics of the spine, with a mandatory assessment of the state of the back and gluteal muscles. Often, at this initial stage, a presumptive diagnosis can be made, and treatment initiated for common conditions like muscular low back pain or pain related to degenerative disc disease.

Imaging and Other Diagnostic Procedures

Based on the findings of the clinical examination, the following additional diagnostic procedures may be prescribed if needed to clarify the diagnosis, especially if "red flag" symptoms are present or conservative treatment fails:

- X-ray of the Lumbosacral Spine: Often performed with functional tests (flexion-extension views) to assess for instability (spondylolisthesis), degenerative changes (spondylosis, spondyloarthrosis), fractures, or gross alignment issues.

- CT Scan of the Lumbosacral Spine: Provides detailed images of bony structures, useful for evaluating complex fractures, severe degenerative bone changes, spinal stenosis, or assessing bone fusion after surgery.

- MRI of the Lumbosacral Spine: The gold standard for visualizing soft tissues, including intervertebral discs (protrusions, herniations, extrusions), the spinal cord and cauda equina (for compression), nerve roots, ligaments, and detecting inflammation (e.g., discitis, spondylitis, sacroiliitis) or tumors.

- Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS): Can help identify nerve root damage (radiculopathy) or peripheral neuropathy if suspected.

- Blood Tests: To screen for infection, inflammation (ESR, CRP), metabolic bone disorders, or systemic rheumatic diseases.

- Bone Scan (Scintigraphy): May be used to detect areas of increased bone turnover, such as in fractures, infections, tumors, or inflammatory arthritis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the lumbosacral spine is a key diagnostic tool. This image demonstrates a herniated disc at the L5–S1 level, which can cause significant low back pain and sciatica.

Understanding Disc Pathology

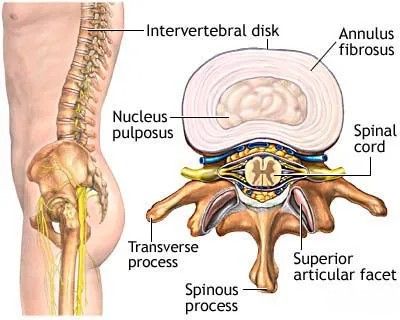

The intervertebral disc, located between adjacent vertebral bodies, consists of a central gelatinous nucleus pulposus surrounded and supported by a tough outer fibrous ring (annulus fibrosus). These discs act as shock absorbers and allow for spinal movement. (More details can be found in the article on the anatomy of the human spine and spinal cord).

With age or injury, the intervertebral discs can degenerate (osteochondrosis). This involves a decrease in the thickness (height) of the discs as they lose water content and elasticity. As the discs thin, the vertebral bodies move closer to each other, which can reduce the size of the intervertebral foramina (openings through which nerve roots exit) and potentially lead to nerve root compression. Degenerative changes can also lead to disc protrusion (bulging of the disc beyond its normal confines) or disc prolapse/herniation/extrusion (rupture of the annulus fibrosus allowing nucleus pulposus material to escape into the spinal canal or foramen). These disc pathologies most often lead to compression of nerve roots, causing radicular pain along the distribution of the affected nerve (e.g., pain radiating to the leg, arm, back of the head, neck, or intercostal spaces, depending on the level of nerve compression), often accompanied by muscle weakness in the areas innervated by that nerve and impaired sensation (numbness, tingling).

Often, a disc protrusion or herniation is accompanied by symptoms of muscular pain (due to protective spasm) or radicular pain along the course of the affected nerve in the leg. This radicular compression symptom can involve a single nerve root or, less commonly, two nerve roots simultaneously.

In addition to nerve compression by a herniated or protruding intervertebral disc in the lumbar spine, the stability of the spinal motor segment (two adjacent vertebrae and the intervening disc and ligaments) may also be impaired. This spinal instability can lead to abnormal vertebral displacement:

- Anterolisthesis: Forward displacement of a vertebra relative to the one below it.

- Retrolisthesis: Backward displacement of a vertebra relative to the one below it.

To clarify the diagnosis of spinal instability, an X-ray of the lumbosacral spine with functional tests (flexion and extension views) may be required.

Most commonly, symptoms of nerve root compression from a herniated or protruding intervertebral disc in the lumbar spine involve the nerve bundles that form the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve is composed of fibers from the L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3 spinal nerves.

Spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal) can lead to compression of the spinal cord or cauda equina, causing significant neurological symptoms.

A focus of chronic inflammation within the spinal canal can lead to its narrowing (stenosis of the spinal canal) and compression of the nerves (cauda equina) or spinal cord (if stenosis is higher up) passing through it. That is why in cases of spinal canal stenosis, it is always necessary to carry out a full course of treatment, utilizing a comprehensive array of different therapeutic methods. If conservative treatment proves ineffective, surgical intervention may be required to decompress the neural elements.

Treatment of Lumbar Spine Pain

The therapeutic approach for low back pain, whether due to degenerative disc disease, disc herniation, or disc protrusion, depends on the severity of symptoms, the underlying cause, and the patient's overall condition. A multimodal approach is often most effective.

Conservative Management

Conservative treatment includes:

- Drug Therapy:

- NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs): To reduce pain and inflammation (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, celecoxib).

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen or, for more severe pain, opioid analgesics (used cautiously and for short durations due to risks of dependence and side effects).

- Muscle Relaxants: To alleviate painful muscle spasms (e.g., cyclobenzaprine, tizanidine).

- Neuropathic Pain Medications: For radicular pain (sciatica), drugs like gabapentin, pregabalin, or tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) may be prescribed.

- Hormones (Corticosteroids): Oral corticosteroids may be used for short periods during severe acute exacerbations to reduce inflammation. Epidural steroid injections are a more targeted approach (see below).

- Activity Modification and Rest: Relative rest during acute severe pain, avoiding activities that aggravate pain. Prolonged bed rest is generally not recommended. Gradual return to activity is encouraged.

- Patient Education: Understanding the condition, proper body mechanics, lifting techniques, and self-management strategies.

Therapeutic Injections

Therapeutic injections (blockades) with local anesthetics and/or corticosteroid medications can provide significant pain relief and reduce inflammation, accelerating recovery. These are often performed under imaging guidance (fluoroscopy or ultrasound) for accuracy:

- Epidural Steroid Injections: Medication is injected into the epidural space around the spinal nerve roots to reduce inflammation associated with disc herniations or spinal stenosis.

- Facet Joint Injections: Medication is injected into or around the facet (zygapophyseal) joints if facet joint arthropathy is suspected as the pain source. Low doses of anesthetic (e.g., novocaine/procaine, lidocaine) and a corticosteroid (e.g., cortisone, diprospan/betamethasone, Kenalog/triamcinolone) are typically used.

- Selective Nerve Root Blocks: Medication is injected around a specific spinal nerve root to diagnose and treat radicular pain.

- Trigger Point Injections: Injection of local anesthetic, sometimes with a corticosteroid, into painful trigger points within muscles.

- Sacroiliac Joint Injections: If sacroiliitis or sacroiliac joint arthrosis is the cause of pain.

When combined with a properly selected physiotherapy regimen, these therapeutic blocks can have a good and long-term effect on lumbar and sacral pain (sacrodynia), particularly in cases of herniated discs or disc protrusions in patients with degenerative disc disease.

Manual Therapy and Physiotherapy

- Manual Therapy: Techniques performed by trained therapists, such as spinal mobilization or manipulation, soft tissue mobilization (massage), and specific muscle energy or radicular techniques, can help relieve pain, reduce muscle spasm, and improve joint mobility. A non-surgical "reduction" of a vertebral disc herniation using these methods may be attempted by some practitioners, focusing on restoring biomechanics and decompressing affected structures.

- Physiotherapy (Physical Therapy): A cornerstone of low back pain management. Includes:

- Exercise Therapy: Specific exercises to strengthen core muscles (abdominal, paraspinal), improve flexibility, and promote proper posture (e.g., McKenzie exercises, dynamic lumbar stabilization).

- Modalities: Application of heat, cold, ultrasound, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), or UHF therapy to reduce pain and inflammation.

- Education: On body mechanics, ergonomics, and self-management strategies.

Soft muscle techniques, a form of manual therapy, can be effective in relieving muscle spasms and associated pain in the lumbar region.

Supportive Measures (e.g., Corsets)

Wearing a semi-rigid lumbosacral corset during the treatment of acute back and lower back pain (e.g., associated with degenerative disc disease with a herniated disc or disc protrusion) can help to limit painful range of motion in the lumbar spine. This primarily aids in reducing pain in the area of inflamed intervertebral joints and relieving excessive protective tension and spasm of the back muscles. In such a corset, a patient can often move independently at home and outdoors, and even sit in a car or at their workplace. The need to wear a corset typically diminishes as the acute back pain subsides. However, it is crucial to remember that during the period of exacerbation of pain, physical workloads should be avoided, and rest should be observed. This temporary limitation, combined with ongoing treatment, can significantly shorten recovery time and prevent further progression of the spinal disease.

There are several types of semi-rigid lumbosacral corsets available. They are all selected individually based on size and can be used repeatedly in case of recurrence of pain, as well as for the prevention of possible exacerbations of pain symptoms during certain activities.

This is a variant of a semi-rigid lumbosacral corset designed to help in the treatment of back and lower back pain, particularly when associated with osteochondrosis of the spine accompanied by a herniated or protruding intervertebral disc.

This image shows another design of a semi-rigid lumbosacral corset, also intended to aid in the treatment of back and lower back pain related to spinal osteochondrosis with intervertebral disc herniation or protrusion.

- Acupuncture (Reflexotherapy): Can be very effective in treating back and lower back pain associated with degenerative disc disease, disc herniation, or disc protrusion by modulating pain signals and promoting muscle relaxation.

The use of acupuncture is often very effective in the treatment of back and lower back pain associated with osteochondrosis of the spine when complicated by a herniated or protruding intervertebral disc.

In the treatment of pain radiating to the leg and buttock against the background of degenerative disc disease with a herniated disc or intervertebral disc protrusion, physiotherapy is essential for eliminating soreness and tingling, and restoring sensitivity in the leg affected by sciatic nerve neuritis due to compression.

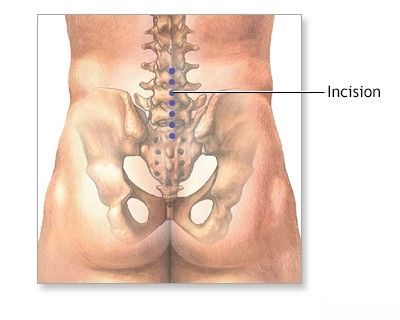

Surgical Treatment (When Indicated)

Surgical intervention is considered if conservative treatment fails to provide adequate relief after a reasonable period (typically 6-12 weeks), or if there are "red flag" signs indicating serious neurological compromise, such as:

- Progressive or severe motor weakness.

- Cauda equina syndrome (bowel/bladder dysfunction, saddle anesthesia, severe bilateral leg weakness - a surgical emergency).

- Intractable pain significantly impacting quality of life despite comprehensive conservative care.

Common surgical procedures for lumbar spine pain include microdiscectomy (for disc herniation), laminectomy or foraminotomy (for spinal stenosis), and spinal fusion (for instability or severe degenerative changes).

Sciatica: Symptoms, Causes, and Duration (Table Summary)

Sciatica refers to pain radiating along the path of the sciatic nerve. While the pain itself often manifests similarly regardless of the exact cause, the specific location and intensity of the pain, along with associated symptoms, can sometimes offer clues about the underlying issue. The duration of sciatica pain also varies depending on the cause and treatment.

Sciatica Pain Location by Possible Cause:

| Cause of Sciatica | Possible Location of Pain | Additional Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Herniated Disc (Lumbar) | Pain radiating from the lower back/buttock down the leg along the path of the affected nerve root (e.g., L4-L5 disc herniation might cause pain in the outer thigh, outer calf, top of foot; L5-S1 might cause pain in posterior thigh, calf, sole of foot). Typically unilateral. | Numbness, tingling (paresthesia), muscle weakness in the affected dermatome/myotome. Pain often worse with sitting, bending, coughing, or sneezing. |

| Spinal Stenosis (Lumbar) | Pain, cramping, or numbness in the lower back, buttocks, thighs, or calves, often bilateral. Symptoms typically worsen with standing or walking (neurogenic claudication) and are relieved by sitting or leaning forward. | Difficulty walking long distances, sensation of heavy legs. |

| Piriformis Syndrome | Pain localized to the buttock, which may radiate down the back of the thigh and leg (mimicking sciatica) due to irritation of the sciatic nerve as it passes near or through the piriformis muscle. | Increased pain with prolonged sitting, hip rotation, or activities that engage the piriformis muscle. Tenderness over the piriformis muscle. |

| Spondylolisthesis (Lumbar) | Lower back pain, often with radiation into the buttocks and posterior thighs/legs if nerve roots are compressed by the vertebral slippage. | Leg weakness, numbness, or tingling. Pain may worsen with extension of the spine. In severe cases, bowel or bladder dysfunction (cauda equina syndrome) can occur. |

| Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction | Pain localized to the buttock, lower back, or groin, can radiate down the posterior thigh (pseudo-sciatica). Usually does not extend below the knee. | Pain worse with prolonged sitting, standing, climbing stairs, or transitioning from sitting to standing. |

Duration of Sciatica Pain by General Cause Category:

| Type of Sciatica | Possible Underlying Cause(s) | Typical Duration (with or without treatment) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Sciatica | Often due to acute lumbar disc herniation, acute muscle strain, or piriformis syndrome flare-up. | Can last from a few days (e.g., 2-3 days) up to several weeks (e.g., 1-2 weeks, sometimes 4-6 weeks). Most acute episodes resolve within this timeframe with conservative care. |

| Subacute Sciatica | Persistent inflammation, ongoing nerve root irritation, moderate spinal stenosis, or slow-to-resolve disc herniation. | Pain lasting from 2-3 weeks up to 6-12 weeks. Requires more intensive conservative management. |

| Chronic Sciatica | Often related to chronic conditions like degenerative disc disease with persistent nerve compression, severe spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis with instability, failed back surgery syndrome, or unresolved nerve damage. | Pain persisting for more than 3 months (12 weeks). May be constant or recurrent over months to years, often requiring long-term management strategies, including consideration for interventional pain procedures or surgery if conservative measures fail. |

Differential Diagnosis of Low Back Pain

It is crucial to differentiate common musculoskeletal low back pain from more serious underlying conditions ("red flag" conditions) or pain referred from other organ systems.

| Category of Pain Origin | Specific Conditions | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal (Common) | Lumbar strain/sprain, Degenerative Disc Disease, Facet Joint Osteoarthritis, Myofascial Pain Syndrome, Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction | Pain often related to posture/activity, improves with rest or specific movements. Localized tenderness, muscle spasm. Neurological exam usually normal unless nerve root impingement. |

| Nerve Root Compression (Radiculopathy) | Lumbar Disc Herniation, Spinal Stenosis (foraminal), Spondylolisthesis | Radiating pain (sciatica), numbness, tingling, weakness in a dermatomal/myotomal pattern. Positive neural tension tests (e.g., SLR). |

| Serious Spinal Pathology ("Red Flags") | Vertebral Fracture (traumatic or osteoporotic), Spinal Tumor (primary or metastatic), Spinal Infection (discitis, osteomyelitis, epidural abscess), Cauda Equina Syndrome | History of trauma, unexplained weight loss, fever, night pain, constant progressive pain, history of cancer, immunosuppression, IV drug use. Neurological deficits (saddle anesthesia, bowel/bladder dysfunction for Cauda Equina Syndrome). |

| Inflammatory Spondyloarthropathies | Ankylosing Spondylitis, Psoriatic Arthritis, Reactive Arthritis, Enteropathic Arthritis | Inflammatory back pain (morning stiffness >30 min, improves with exercise, night pain, insidious onset <45 yrs). Sacroiliitis. Peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, uveitis, rash, IBD. HLA-B27 positive. |

| Referred Pain from Visceral Organs | Kidney stones/infection, Pancreatitis, Aortic Aneurysm, Pelvic Inflammatory Disease, Endometriosis, Prostatitis | Pain often deep, aching, cramping, not clearly related to spinal movement. Associated with symptoms specific to the involved organ system (e.g., urinary symptoms, GI symptoms, fever). |

Prevention and Lifestyle Considerations

Many episodes of low back pain can be prevented or their severity reduced through lifestyle modifications:

- Regular Exercise: Strengthening core (abdominal and back) muscles and maintaining flexibility are crucial. Activities like walking, swimming, and yoga/Pilates can be beneficial.

- Proper Body Mechanics: Using correct techniques for lifting (bend knees, keep back straight), pushing, and pulling.

- Ergonomics: Ensuring an ergonomically sound workspace (chair with good lumbar support, proper desk height, monitor at eye level). Taking frequent breaks from prolonged sitting.

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy body weight reduces stress on the spine.

- Smoking Cessation: Smoking impairs circulation and can accelerate disc degeneration.

- Appropriate Sleeping Surface: A supportive mattress that maintains spinal alignment. Avoid sleeping on overly soft or sagging mattresses.

- Stress Management: Chronic stress can contribute to muscle tension and pain.

Prevention of the development of degenerative disc disease and the appearance of pain symptoms is primarily promoted by independent gymnastics and active recreation. Gymnastics helps to relieve the daily cumulative load on the same muscles, ligaments, and joints of the lumbar spine.

When to Seek Medical Attention

While many episodes of low back pain resolve with self-care, medical attention should be sought if:

- Pain is severe, persistent (lasting more than a few weeks), or disabling.

- Pain results from a significant trauma or injury.

- There are "red flag" symptoms:

- Fever, chills, unexplained weight loss.

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction (incontinence or retention).

- Saddle anesthesia (numbness in the groin, buttocks, inner thighs).

- Progressive or severe weakness in the legs.

- History of cancer or recent infection.

- Pain that is worse at night or not relieved by rest.

- Pain radiates down the leg below the knee, especially if associated with numbness, tingling, or weakness.

- The patient is very young or elderly with new onset of significant back pain.

A healthcare professional can perform a thorough evaluation to determine the cause of the pain and recommend an appropriate treatment plan.

References

- Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001 Feb 1;344(5):363-70.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Oct 2;147(7):478-91.

- Van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, et al. Chapter 3. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2006 Mar;15 Suppl 2:S169-91.

- Bogduk N. Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum. 5th ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2012.

- Wheeler AH, Murrey DB. Chronic lumbar spine and radicular pain: pathophysiology and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2002 Feb;6(1):97-105.

- Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Thomas S. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ. 2006 Jun 17;332(7555):1430-4.

- Atlas SJ, Deyo RA. Evaluating and managing acute low back pain in the primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Feb;16(2):120-31.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Vol. 2. The Lower Extremities. Williams & Wilkins; 1992.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome