Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Understanding Spondylolisthesis (Vertebral Displacement and Spinal Instability)

- Symptoms of Spondylolisthesis and Spinal Instability

- Diagnosis of Spinal Instability and Spondylolisthesis

- Treatment of Spinal Instability and Spondylolisthesis

- Differential Diagnosis of Low Back Pain with Potential Instability

- Complications of Spondylolisthesis

- Prevention and When to Consult a Specialist

- References

Understanding Spondylolisthesis (Vertebral Displacement and Spinal Instability)

Definition and Pathophysiology

Spondylolisthesis refers to the displacement or slippage of one vertebral body relative to the adjacent vertebra below it. This condition is a manifestation of spinal instability, indicating a state of articulation between vertebrae (a spinal motion segment) where excessive or abnormal mobility is present. Such instability and vertebral displacement can lead to irritation or compression of spinal nerve roots, damage to the spinal cord (if occurring at cervical or thoracic levels), or compression of spinal blood vessels (arteries and veins), resulting in a variety of neurological and pain symptoms.

The spinal motion segment, consisting of two adjacent vertebrae, the intervening intervertebral disc, facet joints, and associated ligaments, normally allows for controlled movement while maintaining stability. When this stability is compromised, abnormal translation (slippage) can occur.

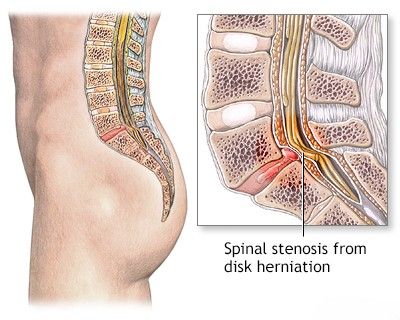

This image illustrates the displacement of vertebrae, known as spondylolisthesis, which results in spinal instability and can lead to the compression of spinal nerves.

Causes and Risk Factors

The reasons for the development of spinal instability and the subsequent displacement of vertebrae (spondylolisthesis) in any part of the spine can be attributed to several factors:

- Congenital/Dysplastic Factors: Congenital abnormalities in the formation of the facet joints or pars interarticularis (a part of the vertebral arch) can predispose to slippage (Type I - Dysplastic Spondylolisthesis).

- Isthmic Factors (Spondylolysis): A defect or fracture in the pars interarticularis (spondylolysis), often due to repetitive stress or trauma in adolescence (e.g., in gymnasts, football linemen), can lead to anterior slippage (Type II - Isthmic Spondylolisthesis).

- Degenerative Changes: Age-related wear and tear of the intervertebral discs and facet joints (osteochondrosis, spondyloarthrosis) can lead to instability and slippage, most commonly in older adults (Type III - Degenerative Spondylolisthesis). Weakness of the articular-ligamentous apparatus contributes significantly.

- Traumatic Injuries: Acute fractures of vertebral elements other than the pars (e.g., pedicles, facets) due to significant trauma (road traffic accidents, falls from a height, lifting excessive weights) can cause acute vertebral displacement (Type IV - Traumatic Spondylolisthesis).

- Pathological Factors: Bone diseases such as tumors (primary or metastatic), infections (spondylitis), or metabolic bone disorders like Paget's disease or osteoporosis can weaken the vertebral structures, leading to slippage (Type V - Pathological Spondylolisthesis). Age-related changes in bone density (osteoporosis) can make vertebrae more susceptible.

- Iatrogenic (Post-Surgical) Factors: Extensive surgical interventions on the spine and spinal cord (e.g., wide laminectomies or facetectomies for decompression) can sometimes destabilize the spine and lead to subsequent spondylolisthesis if adequate stabilization is not achieved (Type VI - Iatrogenic Spondylolisthesis). This can occur when the operating physician needs to extensively remove parts of the patient's vertebrae to ensure an adequate surgical field for accessing the spinal cord or nerve roots.

- Hormonal Factors: During pregnancy, hormonal changes (e.g., increased relaxin) cause a physiological weakening and increased laxity of ligaments, including those supporting the spinal bones, which can contribute to increased mobility or pain, though true spondylolisthesis development solely due to pregnancy is uncommon without pre-existing factors.

Commonly Affected Spinal Regions

While spondylolisthesis can occur at any level of the spine, it is most frequently observed in the following regions due to biomechanical stresses:

- Lumbosacral Spine: Displacement of the L5 vertebra on the S1 vertebra (L5-S1 spondylolisthesis) is the most common site, followed by L4 on L5.

- Cervical Spine: Displacement of vertebrae in the cervical spine can also occur, often related to trauma, degenerative changes, or congenital anomalies.

Classification of Spondylolisthesis (Wiltse Classification)

The Wiltse classification is a widely used system that categorizes spondylolisthesis based on its etiology:

- Type I: Dysplastic (Congenital): Due to congenital abnormalities of the upper sacrum or the arch of L5, allowing anterolisthesis.

- Type II: Isthmic: Caused by a defect (spondylolysis) in the pars interarticularis. Subtypes include:

- IIA: Lytic (fatigue fracture of the pars).

- IIB: Elongated but intact pars.

- IIC: Acute fracture of the pars.

- Type III: Degenerative: Resulting from long-standing intersegmental instability and facet joint arthrosis, without a pars defect. Most common in older adults, often at L4-L5.

- Type IV: Traumatic: Caused by an acute fracture in a part of the vertebra other than the pars interarticularis (e.g., pedicles, facets).

- Type V: Pathological: Due to generalized or localized bone disease (e.g., tumor, infection, Paget's disease) weakening the pars, pedicle, or facet joints.

- Type VI: Iatrogenic (Post-Surgical): Occurs as a result of previous spinal surgery that destabilizes the segment (e.g., extensive laminectomy, facetectomy).

The degree of slippage is often graded using the Meyerding classification (Grade I: 0-25% slip, Grade II: 26-50%, Grade III: 51-75%, Grade IV: 76-100%, Grade V: >100% slip - spondyloptosis).

Symptoms of Spondylolisthesis and Spinal Instability

The clinical manifestations of spondylolisthesis and spinal instability vary widely depending on the location and degree of vertebral slippage, the presence and severity of nerve root or spinal cord compression, and the underlying cause. Some individuals may be asymptomatic, with spondylolisthesis discovered incidentally on imaging.

Common symptoms include:

- Low Back Pain: This is the most frequent symptom, especially in lumbar spondylolisthesis. The pain may be dull, aching, or sharp, and can be localized to the lower back or radiate to the buttocks. It is often exacerbated by activity (especially extension or prolonged standing/walking) and relieved by rest or flexion.

- Radicular Pain (Sciatica): If the slipped vertebra compresses or irritates a spinal nerve root, pain can radiate down the leg along the distribution of that nerve. This may be accompanied by numbness, tingling (paresthesia), or muscle weakness in the leg or foot.

- Neurogenic Claudication: In cases of associated spinal stenosis due to spondylolisthesis, patients may experience pain, cramping, numbness, or weakness in the legs that is provoked by walking or standing and relieved by sitting or leaning forward.

- Muscle Spasms: Hamstring tightness and paraspinal muscle spasms are common.

- Altered Posture or Gait: Patients may develop a swayback posture (increased lumbar lordosis) or a waddling gait. A palpable "step-off" may be felt over the spinous processes at the level of the slip.

- Reduced Spinal Mobility: Stiffness and limited range of motion in the affected spinal segment.

- Cauda Equina Syndrome (Rare but Serious): In severe cases of high-grade lumbar spondylolisthesis, compression of the cauda equina can lead to bowel or bladder dysfunction, saddle anesthesia (numbness in the groin and perineum), and severe bilateral leg weakness. This is a surgical emergency.

- Cervical Spondylolisthesis Symptoms: May include neck pain, radiating arm pain (cervical radiculopathy), myelopathy (if spinal cord compression occurs, leading to gait disturbance, clumsiness, weakness, or spasticity in limbs), and headaches. Signs of cerebral ischemia (e.g., dizziness, visual disturbances) can occur if vertebral artery flow is compromised by cervical instability, though this is less common.

Diagnosis of Spinal Instability and Spondylolisthesis

Diagnosing vertebral instability and spondylolisthesis involves a combination of clinical evaluation and imaging studies:

- Medical History and Physical Examination: Detailed assessment of symptoms, onset, aggravating/relieving factors, history of trauma or relevant medical conditions. Physical examination includes assessment of posture, spinal range of motion, palpation for tenderness or step-offs, neurological examination (motor strength, sensation, reflexes), and provocative tests for nerve root tension (e.g., straight leg raise).

- Imaging Studies:

- X-rays of the Spine: Standing lateral, anteroposterior (AP), and oblique views are standard. Lateral X-rays are crucial for identifying and grading the spondylolisthesis (Meyerding classification). **Functional X-rays (flexion and extension views)** are particularly important for diagnosing instability, as they can demonstrate abnormal movement or an increase in slippage between vertebrae during motion. This is especially relevant when examining the lumbar or cervical spine.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): While X-rays show bony alignment, MRI is superior for visualizing soft tissues, including the intervertebral discs, ligaments, nerve roots, and spinal cord. It can detect disc herniations, spinal stenosis, nerve root compression, and ligamentous injury. MRI with functional tests (flexion and extension views while in the scanner) can also assess instability, though this is less commonly performed than dynamic X-rays.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan of the Spine: Provides excellent detail of bony anatomy and is particularly useful for assessing pars interarticularis defects (spondylolysis), fractures, or the extent of bony stenosis. It can also be used with myelography (CT myelogram) to visualize neural compression if MRI is contraindicated.

Through these imaging techniques, the degree and nature of spinal instability and the specific characteristics of the spondylolisthesis within a spinal motion segment can be accurately visualized and assessed.

This Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the cervical spine (sagittal view) demonstrates straightening of the normal cervical lordosis and anterior displacement (spondylolisthesis, indicated by the arrow) of the C5 vertebral body relative to C6, a sign of spinal instability.

Displacement of vertebrae (spondylolisthesis) can occur due to weakness or injury of the ligamentous apparatus of the cervical spine, often following a neck injury.

Treatment of Spinal Instability and Spondylolisthesis

The method of treating spinal instability and any displacement of a vertebra or several vertebrae (spondylolisthesis) depends significantly on several factors. These include the degree of vertebral displacement (e.g., Meyerding grade), the specific type of spondylolisthesis (e.g., isthmic, degenerative), the presence and severity of clinical manifestations in the patient (such as discomfort, pain, muscle weakness below the zone of displacement), evidence of neurological compromise (radiculopathy or myelopathy), and signs of associated conditions like cerebral ischemia (if cervical instability affects vertebral arteries).

Conservative Management

Conservative (non-surgical) treatment is often the first line of approach for spondylolisthesis, especially for low-grade slips (Grade I or II) or if symptoms are mild to moderate and there are no significant neurological deficits. Conservative management aims to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, improve function, and stabilize the spine through strengthening supporting musculature. It includes a variety of manipulations and therapies targeting the structures of the spine:

- Activity Modification: Avoiding activities that exacerbate pain, such as heavy lifting, high-impact sports, or prolonged hyperextension of the spine.

- Pharmacological Therapy:

- NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) to reduce pain and inflammation.

- Analgesics (pain relievers) like acetaminophen.

- Muscle relaxants for acute muscle spasms.

- Neuropathic pain medications (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin) if radicular pain is prominent.

- Physical Therapy (Physiotherapy/Exercise Therapy): This is a cornerstone of conservative treatment. A tailored exercise program focuses on:

- Strengthening core abdominal and paraspinal muscles to improve spinal support.

- Improving flexibility and range of motion (avoiding excessive extension).

- Postural education and correction of biomechanics.

- Specific stabilization exercises.

- Manual Therapy: Techniques such as joint mobilization (gentle, specific movements to restore joint play) or muscle energy techniques may be employed by qualified therapists. However, high-velocity manipulative techniques are generally contraindicated over an unstable segment.

- Massage Therapy (Massotherapy): Can help relieve muscle tension and spasm associated with spondylolisthesis.

- Therapeutic Spinal Traction: Less commonly used now, but historically employed to try to decompress spinal structures.

- Bracing: A lumbosacral or thoracolumbosacral orthosis (brace) may be prescribed, particularly for isthmic spondylolisthesis in adolescents or for acute pain, to limit motion and provide support, though evidence for long-term efficacy is mixed.

- Epidural Steroid Injections or Selective Nerve Root Blocks: Can provide significant temporary relief from radicular pain by reducing inflammation around compressed nerve roots.

- Acupuncture: May offer pain relief for some individuals.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment for spinal instability and spondylolisthesis is considered if:

- Conservative management fails to provide adequate pain relief or functional improvement after an extended period (e.g., 6-12 months).

- There is progressive or severe neurological deficit (e.g., significant muscle weakness, bowel/bladder dysfunction - cauda equina syndrome, which is a surgical emergency).

- The vertebral slippage is high-grade (Meyerding Grade III, IV, or V) or shows evidence of progression.

- There is intractable pain significantly impacting quality of life.

- Documented progressive instability.

The primary goals of surgical treatment are to decompress neural elements (if compressed) and to stabilize the affected spinal segment(s) by achieving a solid bony fusion (arthrodesis). Common surgical procedures include:

- Decompression (e.g., Laminectomy, Foraminotomy): To relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots.

- Spinal Fusion: Involves placing bone graft material between the affected vertebrae to promote them to grow together into a single, solid bone. Fusion can be performed from various approaches:

- Posterolateral Fusion: Bone graft placed along the transverse processes and facets.

- Interbody Fusion: Bone graft or an interbody cage (a device filled with bone graft material) is placed into the disc space after removal of the intervertebral disc. This can be done via posterior approaches (PLIF - Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion; TLIF - Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion), an anterior approach (ALIF - Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion), or lateral approaches (LLIF/XLIF). The figure showing interbody fusion by placing a second cage via a minimally invasive neurosurgical transforaminal approach illustrates one such technique.

- Instrumentation (Internal Fixation): Pedicle screws, rods, plates, or interbody cages are often used in conjunction with fusion to provide immediate stability, hold the vertebrae in the desired position, and enhance fusion rates. Surgical treatment of instability of the cervical spine by anterior fusion might involve fixing the bodies of the cervical vertebrae with a plate and screws after discectomy and graft placement.

- Reduction of Slippage: In some cases, particularly with high-grade slips, an attempt may be made to partially or fully reduce the vertebral displacement before fusion and instrumentation, though this carries higher neurological risks.

Modern surgical techniques often employ minimally invasive approaches to reduce muscle trauma, blood loss, and hospital stay, facilitating quicker recovery.

This image illustrates a surgical treatment for instability of the cervical spine, employing an anterior fusion technique where the vertebral bodies are stabilized by fixation with a plate and screws after placement of a bone graft or interbody device.

The figure depicts an operation for interbody fusion, specifically by placing a second interbody cage to stabilize lumbar vertebrae affected by instability. A minimally invasive neurosurgical transforaminal approach is being utilized on the left side, subsequent to prior pedicle screw placement on the right.

Endoscopic TLIF procedures are seeing the development of various techniques aimed at successfully reducing spondylolisthesis.

Differential Diagnosis of Low Back Pain with Potential Instability

Low back pain in the context of spondylolisthesis needs to be differentiated from other causes, though spondylolisthesis itself can be a primary pain generator or a coexisting factor.

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Spondylolisthesis | Vertebral slippage visible on X-ray/CT/MRI. Pain often worse with extension or prolonged standing/walking. May have radiculopathy or neurogenic claudication. Pars defect in isthmic type. |

| Lumbar Disc Herniation (without significant listhesis) | Predominantly radicular pain (sciatica) in a dermatomal pattern. Positive nerve tension signs. MRI shows disc herniation compressing nerve root. No significant vertebral slippage. |

| Degenerative Spinal Stenosis (without significant listhesis) | Neurogenic claudication (leg pain/numbness with walking/standing, relieved by flexion/sitting). MRI/CT shows canal narrowing from ligamentous hypertrophy, facet arthropathy, disc bulging. |

| Facet Joint Osteoarthritis (Spondyloarthrosis) | Localized low back pain, sometimes referring to buttock/thigh. Pain worse with extension, twisting. Tenderness over facet joints. Imaging shows facet arthropathy. |

| Myofascial Pain Syndrome / Lumbar Strain | Muscular pain, trigger points, often related to overuse or poor posture. No vertebral slippage. Neurological exam normal. |

| Spondylolysis (Pars Defect without significant slippage) | Low back pain, often in young athletes, worse with extension. Pars defect visible on oblique X-rays, CT, or MRI. Minimal or no listhesis. |

Complications of Spondylolisthesis

If left untreated or if progressive, spondylolisthesis can lead to:

- Chronic low back pain and/or leg pain.

- Progressive neurological deficits (weakness, numbness, reflex changes) due to nerve root compression.

- Spinal stenosis and neurogenic claudication.

- Cauda equina syndrome (in severe lumbar cases).

- Postural deformities (e.g., hyperlordosis, flattened lumbar spine).

- Gait abnormalities.

- Reduced physical function and quality of life.

Prevention and When to Consult a Specialist

While congenital forms are not preventable, reducing risk factors for degenerative or isthmic spondylolisthesis involves:

- Maintaining strong core and back muscles.

- Using proper techniques in sports and lifting to avoid excessive stress on the lumbar spine.

- Avoiding activities that cause repetitive hyperextension, especially in adolescents.

- Maintaining a healthy weight.

Consultation with a neurosurgeon or orthopedic spine specialist is recommended if:

- Back pain or leg pain is severe, persistent, or progressive despite conservative measures.

- There are significant or worsening neurological symptoms (weakness, numbness, bowel/bladder changes).

- Spondylolisthesis is high-grade or shows evidence of progression on imaging.

- Symptoms significantly impact daily activities and quality of life.

A specialist can provide an accurate diagnosis, grade the spondylolisthesis, and recommend the most appropriate treatment plan based on individual circumstances.

References

- Wiltse LL, Newman PH, Macnab I. Classification of spondylolisis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976 Jun;(117):23-9.

- Meyerding HW. Spondylolisthesis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1932;54:371-377. (Original grading system)

- Fredrickson BE, Baker D, McHolick WJ, Yuan HA, Lubicky JP. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984 Jun;66(5):699-707.

- North American Spine Society (NASS). Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care: Diagnosis and Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. 2nd ed. NASS; 2014.

- Matz PG, Meagher RJ, Lamer T, et al. Guideline summary review: an evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Spine J. 2016 Mar;16(3):439-48.

- Kalpakcioglu B, Altinbilek T, Senel K. Determination of spondylolisthesis in low back pain by clinical evaluation. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22(1):27-32.

- Corniola MV, Stienen MN, Joswig H, et al. Surgical versus conservative treatment for patients with degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: A prospective, multicenter, cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0224291.

- Schulte TL, Lerner T, Hackenberg L, Liljenqvist U, Bullmann V. Correlation of clinical and radiographic results after surgery for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(1):E2.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome