Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Understanding Spinal Bacterial (Purulent) Epiduritis

- Clinical Presentation and Symptoms of Spinal Epiduritis

- Diagnosis of Spinal Bacterial (Purulent) Epiduritis

- Treatment of Spinal Bacterial (Purulent) Epiduritis

- Prognosis

- Differential Diagnosis of Acute Back Pain with Fever/Neurological Deficits

- Complications and Prevention

- When to Seek Urgent Medical Attention

- References

Understanding Spinal Bacterial (Purulent) Epiduritis

Definition and Pathophysiology

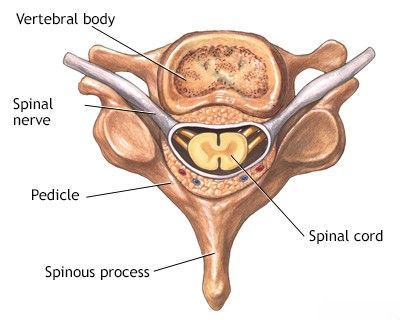

Spinal purulent epiduritis, often referred to as a spinal epidural abscess (SEA), is a serious and potentially devastating infection characterized by a collection of pus within the epidural space. The epidural space is the area between the dura mater (the outermost membrane covering the spinal cord and brain) and the vertebral bones of the spinal canal. This space normally contains epidural fatty tissue, blood vessels, and nerve root sleeves.

If the purulent collection is localized and encapsulated, it is termed an epidural abscess. If the inflammation and pus are diffuse and spread along tissue planes without clear boundaries, it is referred to as epidural phlegmon. Spinal epiduritis is considered a neurosurgical emergency because the accumulating pus can compress the spinal cord or cauda equina, leading to rapidly progressive and often irreversible neurological deficits, including paralysis and sensory loss. Sometimes, the infection can spread through the dura mater to involve the linings of the brain (meninges) or even the substance of the spinal cord or brain, leading to a more extensive meningomyelitis process.

Etiology and Routes of Infection

The cause of acute purulent spinal epiduritis is the introduction and proliferation of pathogenic bacteria within the epidural space. Infection can reach this space through several routes:

- Hematogenous Spread (Most Common): Bacteria from a distant purulent focus in the body (e.g., skin boils/furuncles, subcutaneous abscesses, infected wounds like panaritium, cellulitis/phlegmon, urinary tract infections, endocarditis, pneumonia) can travel through the bloodstream and seed the epidural space. The rich venous plexus in the epidural space (Batson's plexus) is valveless, allowing for retrograde flow and bacterial seeding.

- Direct Extension (Contiguous Spread): Infection from adjacent structures, such as vertebral osteomyelitis (infection of the vertebral bone), discitis (infection of the intervertebral disc), psoas abscess, or retropharyngeal abscess, can spread directly into the epidural space.

- Iatrogenic Introduction: As a complication of spinal procedures, such as epidural anesthesia or analgesia, lumbar puncture, spinal surgery, or other invasive spinal interventions, if aseptic technique is breached. A possible reason for the formation of purulent spinal epiduritis in women can also be recent gynecological manipulations, though this is less common and usually implies a secondary bacteremia.

- Traumatic Introduction: Penetrating trauma to the spine can directly introduce bacteria into the epidural space.

- Lymphatic Pathways: Less commonly, infection may spread via lymphatic channels from nearby infected tissues.

The most common causative organism is *Staphylococcus aureus*. Other implicated bacteria include Streptococci, Gram-negative bacilli (e.g., *Escherichia coli*, *Pseudomonas aeruginosa*), and anaerobes. Risk factors for developing spinal epiduritis include diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug use, alcoholism, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression (e.g., HIV infection, corticosteroid use), recent spinal trauma or surgery, and indwelling vascular catheters.

Pus (fibrin in older texts) more often accumulates in the posterior epidural space due to its larger potential volume and looser areolar tissue compared to the anterior epidural space, where the dura is more adherent to the posterior longitudinal ligament.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms of Spinal Epiduritis

Acute purulent spinal epiduritis typically develops rapidly and progresses through several stages if untreated, though the presentation can be variable:

- Back Pain: This is usually the earliest and most common symptom. The pain is often severe, localized to the affected spinal level, and may be exacerbated by percussion (tapping) over the spine or movement.

- Nerve Root Pain (Radicular Pain): As the inflammation or abscess compresses nerve roots, patients develop sharp, shooting, or burning pain radiating along the distribution of the affected nerve root(s). This is often described as "radicular pain."

- Neurological Deficits (Spinal Cord or Cauda Equina Compression): If the spinal cord or cauda equina becomes compressed, neurological symptoms appear and can progress rapidly. These include:

- Motor weakness or paralysis (paresis or plegia) in the limbs below the level of compression.

- Sensory disturbances (numbness, tingling, loss of sensation) below the level of compression.

- Bowel and bladder dysfunction (urinary retention, incontinence, constipation).

- Hyperreflexia, spasticity, and positive Babinski sign (if spinal cord compression).

- Areflexia, flaccid weakness (if cauda equina or nerve root compression predominates).

- Systemic Symptoms of Infection:

- Fever (often high, e.g., 39-40 °C or 102.2-104 °F).

- Chills and rigors.

- Malaise, general serious condition.

- Tachycardia.

Consciousness is usually preserved unless there are severe systemic complications like sepsis or associated intracranial infection. Patients often experience acute radicular pain and pain in the occiput (if cervical epiduritis) or spine, accompanied by both sensory and motor disorders of a radicular nature.

If the spinal epiduritis does not cause significant spinal cord compression, then conduction deficits (long tract signs like paralysis or widespread sensory loss below a certain level) may not be present. However, when the spinal cord is compressed and myelitis (inflammation of the spinal cord itself) occurs, gross paresis, paralysis, dysfunction of the pelvic organs, trophic disorders (such as bedsores/pressure ulcers), and urosepsis (sepsis originating from the urinary tract due to bladder dysfunction) can appear rapidly.

Diagnosis of Spinal Bacterial (Purulent) Epiduritis

Early diagnosis of spinal epiduritis is critical due to the risk of rapid neurological deterioration. A high index of suspicion is required, especially in patients with risk factors presenting with back pain and fever or neurological symptoms.

Diagnostic Triad and Lumbar Puncture

A classic diagnostic triad for spinal epiduritis has been identified, though not all components are always present initially:

- Presence of a purulent or infectious focus elsewhere in the body (or recent spinal procedure/trauma).

- Radicular syndrome (nerve root pain and/or deficits).

- Spinal cord or cauda equina compression syndrome (motor weakness, sensory level, bowel/bladder dysfunction).

Lumbar Puncture (LP) can be of diagnostic value if epiduritis is suspected, but it must be performed with extreme caution. If an epidural abscess is present at the puncture site, there is a risk of introducing infection into the subarachnoid space and causing meningitis. Therefore, MRI is usually performed *before* LP if an epidural abscess is strongly suspected. If LP is performed:

- Undoubted evidence of epiduritis is the aspiration of pus directly from the epidural space when the needle enters this space (before piercing the dura). This is rare and usually indicates a large collection.

- If the spinal cord is not compressed by the epiduritis, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis may show pleocytosis (increased white blood cells, often neutrophils) and elevated protein, but glucose may be normal, and cultures negative if meningitis is not present.

- If there is significant spinal cord compression leading to a block of CSF flow, protein-cell dissociation (very high protein with few or normal cells – Froin's syndrome) may be found in the CSF obtained below the level of the block.

- CSF cultures are essential if meningitis is suspected.

Imaging Studies

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with Gadolinium Contrast: This is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing spinal epidural abscess and epiduritis. MRI can clearly delineate the location and extent of the abscess/phlegmon, assess for spinal cord compression or ischemia, identify associated vertebral osteomyelitis or discitis, and differentiate from other spinal pathologies. The abscess typically appears as a collection that is T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense, and shows peripheral rim enhancement with gadolinium.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan with Contrast: CT can show bony destruction from osteomyelitis and may identify an epidural collection, especially if combined with myelography (CT myelogram). However, MRI is generally superior for visualizing soft tissue infection and spinal cord pathology. CT is useful if MRI is contraindicated or unavailable.

- Laboratory Tests: Elevated white blood cell count (leukocytosis), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) are common but non-specific indicators of infection/inflammation. Blood cultures should be obtained as they are positive in a significant percentage of cases and can identify the causative organism.

An MRI scan demonstrating a spinal epidural abscess, which is a collection of pus in the epidural space causing compression of the spinal cord.

Treatment of Spinal Bacterial (Purulent) Epiduritis

The management of spinal epiduritis is a medical and surgical emergency aimed at eradicating the infection, decompressing neural elements, preserving neurological function, and maintaining spinal stability.

Medical Management

- Intravenous Antibiotics: Intensive, empirical broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy should be initiated immediately after blood cultures (and CSF/pus cultures if obtained) are drawn. The antibiotic regimen should cover *Staphylococcus aureus* (including MRSA if local prevalence is high), Streptococci, and Gram-negative bacilli. Common empiric regimens might include vancomycin plus a third or fourth-generation cephalosporin (e.g., ceftriaxone, cefepime) or a carbapenem. Therapy is then tailored based on culture and sensitivity results. Long courses of IV antibiotics (typically 4-8 weeks or longer) are usually required, sometimes followed by oral antibiotics.

- Sulfa Drugs (Sulfonamides): Historically, sulfa drugs were used, often in combination with other agents, but their role as primary therapy has diminished with the availability of more potent antibiotics, though they may still have a place in specific situations or based on sensitivities.

- Pain Management: Adequate analgesia is essential.

- Supportive Care: Including hemodynamic support if sepsis is present, nutritional support, and management of underlying medical conditions.

Surgical Intervention

Surgical intervention is often necessary, particularly if there is significant spinal cord or cauda equina compression with neurological deficits, a large abscess collection, failure to improve with conservative (antibiotic) therapy within 24-48 hours, or spinal instability.

- Surgical Decompression and Drainage: The primary surgical goal is to decompress the neural elements by evacuating the epidural pus or phlegmon. This is most commonly achieved via laminectomy (removal of the posterior vertebral arch) at the affected levels to expose and drain the epidural space. Debridement of infected or necrotic tissue is also performed. Cultures of surgical specimens are critical.

- Spinal Stabilization: If there is associated vertebral osteomyelitis leading to significant bone destruction and spinal instability, spinal fusion and instrumentation may be required, either at the time of initial decompression or as a staged procedure.

The decision between conservative therapy alone versus antibiotics plus surgery depends on several factors, including the patient's neurological status, the extent of the abscess, the presence of systemic sepsis, and the causative organism. Patients with rapidly progressive neurological deficits or significant cord compression generally require urgent surgical decompression.

Prognosis

The prognosis for spinal epiduritis depends heavily on the patient's neurological status at the time of diagnosis and initiation of treatment, the virulence of the infecting organism, and the timeliness of surgical decompression if indicated. If spinal epiduritis does not extend to involve the substance of the spinal cord (myelitis) or brain (meningitis, encephalitis) and is treated promptly before severe, irreversible neurological damage occurs, the prognosis can be favorable with a good chance of neurological recovery. However, delays in diagnosis and treatment can lead to permanent paralysis, sensory loss, bowel/bladder dysfunction, or even death, especially if severe sepsis or widespread infection develops. Patients with pre-existing debilitating conditions or rapidly progressing neurological deficits tend to have poorer outcomes.

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Back Pain with Fever/Neurological Deficits

Spinal epiduritis must be differentiated from other conditions causing acute back pain, fever, and/or neurological symptoms:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Spinal Epiduritis / Epidural Abscess | Severe localized back pain, fever, radicular pain, progressive neurological deficits (weakness, sensory loss, bowel/bladder dysfunction). MRI shows epidural collection/inflammation with cord compression. Elevated inflammatory markers. |

| Vertebral Osteomyelitis / Discitis | Localized back pain, fever, tenderness over spine. Neurological deficits less common unless complicated by epidural abscess or instability. MRI shows vertebral body/disc inflammation/destruction. |

| Bacterial Meningitis | Fever, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, altered mental status. CSF shows purulent meningitis. Neurological deficits can occur but often more diffuse initially. Spine imaging may be normal unless complicated. |

| Transverse Myelitis | Acute/subacute onset of bilateral weakness, sensory level, bowel/bladder dysfunction. Back pain and fever may occur. MRI shows intrinsic spinal cord inflammation/demyelination, no epidural collection. CSF may show inflammation. |

| Acute Disc Herniation with Radiculopathy/Myelopathy | Sudden onset of severe radicular pain or myelopathic symptoms. Fever usually absent unless complicated by discitis. MRI shows disc herniation compressing neural elements. |

| Spinal Metastasis with Cord Compression | History of cancer, progressive back pain (often worse at night), neurological deficits. Fever usually absent unless co-infection. MRI shows tumor compressing cord. |

| Guillain-Barré Syndrome | Ascending symmetrical weakness/paralysis, areflexia, sensory disturbances. Often follows infection. Back pain common. CSF shows albuminocytologic dissociation. No fever unless intercurrent infection. |

Complications and Prevention

Potential complications of spinal epiduritis are severe and include:

- Permanent paralysis (paraplegia, quadriplegia).

- Chronic pain.

- Irreversible sensory loss.

- Permanent bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction.

- Spinal deformity or instability if significant bone destruction occurs.

- Sepsis and death.

Prevention strategies involve:

- Prompt and effective treatment of skin and soft tissue infections, and other potential sources of bacteremia.

- Strict aseptic technique during spinal procedures.

- Early recognition and management of vertebral osteomyelitis or discitis.

- Maintaining good immune health and managing conditions like diabetes that increase infection risk.

When to Seek Urgent Medical Attention

Spinal epiduritis is a neurological emergency. Any individual presenting with the combination of significant back pain, fever, and new or progressive neurological symptoms (weakness, numbness, difficulty urinating or defecating) should seek immediate medical evaluation in an emergency department. Timeliness of diagnosis and intervention is paramount to improving outcomes.

References

- Darouiche RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 9;355(19):2012-20.

- Reihsaus E, Waldbaur H, Seeling W. Spinal epidural abscess: a meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2000 Sep;23(3):175-204.

- Sendi P, Bregenzer T, Zimmerli W. Spinal epidural abscess in clinical practice. QJM. 2008 Jan;101(1):1-12.

- Davis DP, Wold RM, Patel RJ, et al. The clinical presentation and impact of diagnostic delays on emergency department patients with spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med. 2004 Apr;26(3):285-91.

- Hlavin ML, Kaminski HJ, Ross JS, Ganz E. Spinal epidural abscess: a ten-year perspective. Neurosurgery. 1990 Aug;27(2):177-84.

- Curry WT Jr, Hoh BL, Amin-Hanjani S, Eskandar EN. Spinal epidural abscess: clinical presentation, management, and outcome. Surg Neurol. 2005 Jan;63(1):364-71; discussion 371.

- Rigamonti D, Liem L, Sampath P, et al. Spinal epidural abscess: contemporary trends in etiology, evaluation, and management. Surg Neurol. 1999 Sep;52(3):189-96; discussion 196-7.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome