Spinal spondylosis

Understanding Spinal Spondylosis

Definition and Pathophysiology

Spondylosis is a broad term referring to age-related degenerative changes affecting the spine. It is a dystrophic process that, unlike osteochondrosis of the spine (which primarily involves degeneration of the intervertebral disc nucleus pulposus and endplates), often begins with changes in the outer parts of the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral discs. Radiographically, spondylosis is commonly characterized by the presence of marginal bone growths called osteophytes (bone spurs) that form along the edges of the vertebral bodies, often surrounding the intervertebral disc. Typically, the height of the intervertebral disc itself may not significantly change in early or isolated spondylosis, and the contours of the vertebral bodies remain relatively even.

Spondylosis can occur in any part of the spine but is frequently localized in the thoracic spine. It is also commonly observed in the lumbar and cervical spine, where it can lead to more significant clinical symptoms due to the mobility of these regions and the proximity of neural structures.

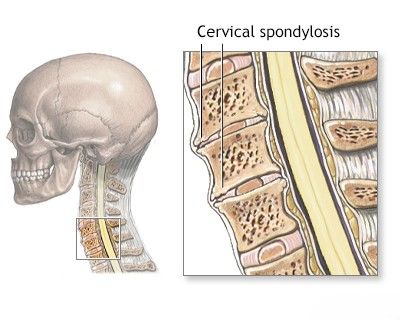

Cervical Spondylosis and its Complications

The term "spondylosis" is often used to describe a spectrum of degenerative diseases of the spine that can result in compression of the spinal cord (myelopathy) and/or adjacent nerve roots (radiculopathy). Cervical spondylosis with compression of the spinal cord (Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy - CSM) and nerve roots is more common in older individuals, particularly men. It is characterized by a combination of degenerative changes, including:

- Narrowing of the intervertebral disc spaces, sometimes with the formation of a hernia of the nucleus pulposus (herniated disc) or bulging of the annulus fibrosus.

- Formation of osteophytes from the posterior and posterolateral surfaces of the vertebral bodies, encroaching on the spinal canal or neural foramina.

- Partial subluxation (misalignment) of the vertebrae, contributing to spinal instability.

- Hypertrophy (thickening) of the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum.

- Hypertrophy of the intervertebral (facet) joints, leading to spondyloarthrosis and further narrowing of the spinal canal and neural foramina.

Types and Causes of Spinal Spondylosis

Spondylosis is commonly viewed as a manifestation of the natural aging process of the spine. However, other types and contributing factors exist:

- Static Spondylosis: Can be a consequence of premature wear and tear of the intervertebral discs due to abnormal axial loading on the spine. This may result from an incorrectly fused spinal fracture, severe kyphosis or scoliosis (structural deformities).

- Spontaneous Spondylosis (Primary Degenerative Spondylosis): Arises from age-related and sometimes early (premature) wear and tear of the intervertebral discs and facet joints. Genetic predisposition and lifestyle factors (e.g., heavy labor, smoking) can influence its development.

- Reactive Spondylosis: Develops due to damage to the vertebrae caused by an inflammatory process, such as spondylitis (e.g., infectious or autoimmune).

Spondylosis can often coexist with osteochondrosis of the spine, representing different facets of the overall degenerative cascade. In childhood and adolescence, significant spondylosis is relatively rare and typically does not play a major role in causing diseases of the peripheral nervous system unless associated with congenital anomalies or severe trauma.

Bone changes in spondylosis occur as a result of degenerative and reactive inflammatory processes, although patients may not exhibit signs of true systemic arthritis (like rheumatoid arthritis).

Educational video explaining Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy.

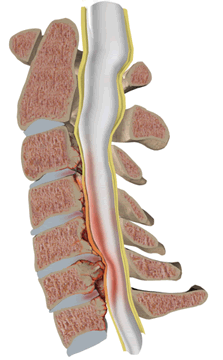

The formation of a "spondylotic bar," which consists of osteophytes growing from the posterior surface of the vertebral bodies, can cause direct compression of the anterior surface of the spinal cord, leading to symptoms of myelopathy. Lateral growth of osteophytes, accompanied by hypertrophic changes in the facet joints, can encroach upon the intervertebral foramina (the exit points for spinal nerve roots), often leading to radicular symptoms (radiculopathy).

The anteroposterior (longitudinal) diameter of the spinal canal can also decrease due to disc protrusion or extrusion, and hypertrophy or protrusion of the posterior longitudinal ligament. This narrowing can be exacerbated by neck extension. Even though radiographic signs of spondylosis are commonly found in elderly individuals, only a subset of these patients develops symptomatic compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots leading to myelopathy or radiculopathy. This discrepancy may be partly due to variations in the congenital (original) size of the spinal canal; individuals with a congenitally narrower canal are more susceptible to symptomatic compression from degenerative changes.

Clinical Symptoms of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CSM) and Radiculopathy

The initial symptoms of spinal cord and nerve root compression in cervical spondylosis often include neck pain and shoulder pain. These complaints can be accompanied by a limitation of head and neck movement. Compression of nerve roots (radiculopathy) is characterized by radicular pain radiating into the arm along the distribution of the affected cervical nerves (commonly C5, C6, C7), potentially with associated numbness, tingling (paresthesia), and weakness in the arm or hand.

Compression of the cervical spinal cord (myelopathy) causes slowly progressive spastic paraparesis (weakness and stiffness) of the limbs, which can be asymmetric. Symptoms of myelopathy often include:

- Paresthesias (numbness, tingling) in the feet and hands.

- Gait disturbance and imbalance.

- Loss of fine motor skills in the hands (e.g., difficulty with buttons, handwriting).

- Weakness and spasticity in the legs.

- Vibration sensitivity in the lower extremities is reduced in most patients; sometimes a distinct sensory level can be determined in the upper chest.

- Provocation of weakness in the legs or pain radiating to the arms or upper shoulder girdle when the patient coughs, sneezes, or strains (Valsalva maneuver).

Neurological examination may reveal:

- Loss of sensation in the hands.

- Atrophy of hand muscles.

- Increased deep tendon reflexes in the legs (hyperreflexia).

- Asymmetric Babinski signs (extensor plantar responses).

- Reduced tendon and periosteal reflexes in the arms if nerve roots are compressed (e.g., reduced biceps reflex with C5-C6 root/cord compression).

In cases of pronounced organic changes due to spondylosis, patients may experience urinary urgency or incontinence. The diagnosis of spondylosis causing myelopathy is often considered when cervical myelopathy develops in older patients, especially with paresthesias in the feet and hands, hand muscle atrophy, gait difficulties, and signs of upper motor neuron involvement in the legs (hyperreflexia, Babinski signs).

Typical Clinical Symptoms and Signs in Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CSM) Patients

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

| Weakness (arms, legs) | Myelopathic signs (general) |

| Gait impairment / Unsteadiness | Hyperreflexia (especially in lower limbs) |

| Numbness or clumsiness of hands | Inverted brachioradialis reflex |

| Spasticity (stiffness in limbs) | Hoffmann’s sign |

| Urinary incontinence or urgency | Ankle clonus |

| Paresthesias (tingling, pins & needles) | Babinski sign (extensor plantar response) |

| Neck pain | Motor deficits (weakness, atrophy) |

| Arm pain (radicular) | Positive Romberg sign (impaired balance with eyes closed) |

| Lhermitte’s sign (electric shock-like sensation down the spine on neck flexion) | |

| Thenar atrophy (wasting of thumb muscles) |

Nurick Grades for Myelopathy (1972)

| Grade | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 0 | Signs or symptoms of nerve root involvement but without evidence of spinal cord disease. |

| 1 | Signs of spinal cord disease but no difficulty in walking. |

| 2 | Slight difficulty in walking which did not prevent full-time employment. |

| 3 | Difficulty in walking which prevented full-time employment or the ability to do all housework, but which was not so severe as to require someone else’s help to walk. |

| 4 | Able to walk only with someone else’s help or with the aid of a frame. |

| 5 | Chair-bound or bedridden. |

Diagnosis of Spondylosis

Clinical Examination

The diagnosis of spondylosis typically begins with a mandatory neurological and orthopedic examination by a physician. During this comprehensive assessment, the patient's neurological status is evaluated, including tests for reflexes, muscle strength, sensation, and coordination. Possible impairments in the biomechanics of the spine are identified, with a mandatory assessment of the state of the back muscles (paravertebral muscles) and gluteal region. Often, even at this initial stage of the study, a presumptive diagnosis can be made for a patient presenting with spinal spondylosis and associated pain in the neck, thoracic region, or lower back, and a preliminary treatment plan can be formulated.

Educational video: CT scan of the spine can be utilized to examine the spine for conditions such as a herniated disk, stenosis, scoliosis, traumatic injuries, tumors, congenital structural issues like spina bifida, blood vessel problems, or infections.

Imaging and Other Diagnostic Procedures

Based on the findings of the neurological and orthopedic examination, if spondylosis with pain symptoms is suspected, the following additional diagnostic procedures may be prescribed to confirm the diagnosis, assess severity, and rule out other conditions:

- X-ray of the Spine: Standard X-rays (e.g., of the lumbosacral or cervical spine) with functional tests (flexion and extension views) can reveal osteophytes ("spondylotic beams"), a decrease in the height of intervertebral discs, subluxation (misalignment) of vertebrae, changes in physiological spinal curves (e.g., straightening of cervical lordosis or development of kyphosis), and a decrease in the spinal canal diameter (e.g., to 11 mm or less, or to 7 mm on cervical spine extension, indicative of stenosis).

- CT Scan of the Spine: Provides more detailed images of the bony structures, osteophytes, facet joint hypertrophy, and canal dimensions.

- MRI of the Spine: The preferred imaging modality for evaluating soft tissues, including intervertebral discs (bulges, herniations), ligaments (hypertrophy), the spinal cord (compression, signal changes indicative of myelopathy), and nerve roots.

- Electrophysiological Tests: Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS/ENG) may be used to assess nerve root or spinal cord dysfunction, helping to differentiate radiculopathy from myelopathy or peripheral neuropathy. Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SSEPs) can reveal normal conduction along large peripheral sensory fibers but a delay in central conduction in the middle and upper cervical segments of the spinal cord in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

Spondylosis is frequently accompanied by muscle pain radiating along a nerve distribution (e.g., down the arm or leg, in the neck, or between the shoulder blades). In addition to muscle tone changes, the stability of the spinal segment can be impaired. Spinal instability may lead to vertebral displacement, such as anterolisthesis (forward slippage) or retrolisthesis (backward slippage). X-rays with functional views are particularly useful for diagnosing such instability.

A focus of chronic inflammation or degenerative changes within the spinal canal can lead to its narrowing (stenosis of the spinal canal) and subsequent compression of the spinal cord and nerve roots passing through it. Therefore, in cases of spinal stenosis, a comprehensive course of treatment utilizing a full arsenal of therapeutic methods is always necessary. If conservative treatment is ineffective, surgical intervention may be considered.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis in patients with spondylosis is often unchanged or may show a slightly increased protein content, but typically no significant inflammation.

MRI Classification of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CMS)

Several MRI-based grading systems exist to classify the severity of spinal cord compression in Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. One such simplified illustrative classification based on MRI studies could be:

Cervical spine MRI. Grade 0 - Physiologic alignment, no cord compression.

Cervical spine MRI. Grade I - Disc pathology, spinal canal narrowing present, but no visible impingement on the spinal cord.

Cervical spine MRI. Grade II - Spondylosis present with visible anterior impingement on the spinal cord, but no signal change within the cord.

Cervical spine MRI. Grade III - Spondylosis with anterior or posterior impingement on the spinal cord, and evidence of increased signal intensity (e.g., edema, gliosis) within the cord, possibly associated with restricted motion on dynamic views.

Cervical spine MRI. Grade IV - Established Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy (CSM) with significant anterior and/or posterior impingement, often with signs of cord atrophy in addition to signal changes.

Nurick Grades for Myelopathy

The Nurick scale is a widely used clinical grading system to assess the functional severity of myelopathy, particularly CSM:

| Grade | Functional Status |

|---|---|

| 0 | Signs or symptoms of root involvement but no evidence of spinal cord disease. |

| 1 | Signs of spinal cord disease, but no difficulty in walking. |

| 2 | Slight difficulty in walking which did not prevent full-time employment. |

| 3 | Difficulty in walking which prevented full-time employment or the ability to do all housework, but which was not so severe as to require someone else’s help to walk. |

| 4 | Able to walk only with someone else’s help or with the aid of a frame. |

| 5 | Chair-bound or bedridden. |

Treatment of Spondylosis

The treatment for spinal spondylosis depends on the severity of symptoms, the location of the spondylosis (cervical, thoracic, lumbar), the presence and degree of nerve root or spinal cord compression, and the overall health of the patient. Treatment aims to relieve pain, improve function, and prevent further neurological deterioration.

Conservative Management

For mild to moderate spondylosis without significant neurological compromise, conservative treatment is usually the first approach:

Drug Therapy

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Such as ibuprofen or naproxen, to reduce pain and inflammation.

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen (paracetamol) for pain relief. For more severe pain, stronger analgesics, including opioids, may be considered for short-term use under strict medical supervision.

- Muscle Relaxants: To alleviate muscle spasms.

- Neuropathic Pain Medications: Drugs like gabapentin, pregabalin, or certain antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, duloxetine) may be used if there is nerve-related (radicular) pain.

- Hormones (Corticosteroids): Oral corticosteroids may be prescribed for short periods to reduce severe inflammation and pain, particularly during acute flare-ups of radiculopathy. Epidural steroid injections deliver corticosteroids directly near the inflamed nerve roots or spinal cord.

Therapeutic Injections

Injections of medications into specific spinal areas can provide diagnostic information and therapeutic relief:

- Epidural Steroid Injections: Administered into the epidural space to reduce inflammation around nerve roots.

- Facet Joint Injections: Injections of anesthetic and/or corticosteroid into the facet joints (intervertebral joints) can help if facet joint arthropathy is a significant source of pain. These therapeutic blockades, especially when combined with a properly selected physiotherapy regimen, can have a good and long-term effect in relieving pain exacerbations in spondylosis.

- Nerve Root Blocks: Selective injection of anesthetic and steroid around a specific nerve root.

- Trigger Point Injections: For associated myofascial pain in the muscles.

Manual Therapy

Techniques performed by qualified therapists (e.g., physiotherapists, chiropractors, osteopaths) can be beneficial. These may include:

- Muscle techniques: Soft tissue mobilization, massage, myofascial release.

- Articular (joint) techniques: Mobilization or gentle manipulation of spinal joints to improve range of motion and reduce pain.

- Radicular techniques (neural mobilization): Gentle techniques to address nerve root irritation.

Physiotherapy

Physical therapy plays a crucial role in managing spondylosis. A tailored program may include:

- Exercises to improve strength, flexibility, and endurance of spinal and core muscles.

- Postural education and correction.

- Modalities such as heat/cold therapy, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), or ultrasound (UHF) to alleviate pain and muscle spasm.

- Traction: Cervical traction (e.g., with a Glisson loop) may be shown for some patients with cervical spondylosis to relieve nerve root compression.

Physiotherapy is beneficial in treating pain radiating to the leg and buttock (sciatica) associated with spondylosis. It helps eliminate pain and tingling, and restore sensitivity in the leg when the sciatic nerve is compressed by a herniated disc or disc protrusion related to degenerative changes.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture may be used as an adjunctive therapy for pain relief in some patients with spondylosis.

The use of acupuncture can be very effective in the conservative treatment of back and lower back pain associated with spinal spondylosis.

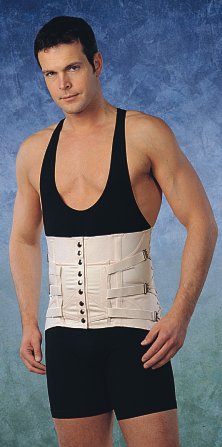

Bracing (Corsets/Collars)

With a mild course of cervical spondylosis, rest and immobilization of the cervical spine using a soft cervical collar (Shantz collar) can be effective for short periods to reduce pain during acute exacerbations. For lumbar spondylosis with back and lower back pain, wearing a semi-rigid lumbosacral brace (corset) helps to limit the range of motion in the lumbar spine. This primarily aids in reducing pain in the area of inflamed facet joints and relieves excessive protective tension and spasm of the back muscles. Patients can often move independently at home and on the street, and even sit in a car or at their workplace while wearing such a corset. The brace is typically no longer needed once the acute back pain subsides. There are several types of semi-rigid lumbosacral braces, selected individually based on size and support needed, and they can be used repeatedly for recurrent pain or for prevention during activities that might exacerbate symptoms.

A variant of a semi-rigid lumbosacral brace, which can help in the treatment of back and lower back pain associated with spondylosis of the spine by providing support and limiting painful movements.

Another variant of a semi-rigid lumbosacral brace, designed to provide support and aid in the treatment of back and lower back pain linked to spinal spondylosis.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery for spondylosis is generally recommended when:

- There is progressive neurological deficit (worsening myelopathy or radiculopathy).

- Intractable pain is unresponsive to comprehensive conservative management.

- Pronounced gait disturbances appear.

- There is significant weakness in the hands or arms.

- Bladder or bowel dysfunction occurs (a sign of severe myelopathy).

- A full cerebrospinal fluid (spinal) block is revealed on myelography (historically) or significant cord compression with signal change is seen on MRI of the spinal cord.

The type of surgery depends on the location and nature of the compression. Common procedures include:

- Decompressive Laminectomy or Laminoplasty: Removal of part of the vertebral arch (lamina) to create more space for the spinal cord, often performed for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Many patients with spinal cord lesions at the cervical level, especially those with conditions like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, or subacute combined degeneration (these are distinct from primary spondylosis but may have coexisting spondylotic changes or similar compressive effects considered for surgery), might undergo laminectomy. Often, after this operation, there can be temporary improvement in neurological status, suggesting partial significance of spondylotic compression. However, if myelopathy was primarily caused by an underlying progressive neurological disease, it will likely continue to progress.

- Discectomy: Removal of a herniated or degenerative disc (e.g., Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion - ACDF).

- Foraminotomy: Enlarging the neural foramen to decompress a nerve root.

- Spinal Fusion: Stabilizing spinal segments, often performed in conjunction with decompression.

Slightly increasing disturbances in gait and sensation in a patient can sometimes be mistaken for manifestations of polyneuropathy, highlighting the need for accurate diagnosis before considering surgery.

Lifestyle and Self-Care

During periods of exacerbation of pain in the back and lower back due to spondylosis, it is crucial to avoid excessive workloads and observe adequate rest. This is a temporary limitation but can significantly shorten recovery time and, in conjunction with ongoing treatment, help prevent further progression of the spinal disease.

Differential Diagnosis of Neck and Back Pain with Neurological Symptoms

Symptoms of spondylosis, particularly cervical spondylotic myelopathy and radiculopathy, can mimic other conditions. A thorough differential diagnosis is essential:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Spinal Spondylosis (with Myelopathy/Radiculopathy) | Age-related degenerative changes on imaging (osteophytes, disc space narrowing, facet hypertrophy). Neck/back pain, radicular pain, progressive weakness, spasticity, sensory changes, gait disturbance, possible bladder/bowel dysfunction. |

| Herniated Intervertebral Disc (Acute) | Often acute onset of radicular pain, numbness, weakness corresponding to a specific nerve root. May occur without significant spondylotic changes, especially in younger individuals. |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | Can cause myelopathy with sensory, motor, and autonomic symptoms. Often relapsing-remitting course, optic neuritis history common. MRI shows demyelinating plaques in brain and spinal cord. |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | Progressive weakness due to degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurons. Sensory system typically spared. EMG characteristic. |

| Spinal Cord Tumors | Progressive neurological deficits, pain often worse at night. MRI with contrast is diagnostic. |

| Peripheral Neuropathy | Sensory loss, weakness, reflex changes often in a "glove and stocking" distribution. EMG/NCS help differentiate from radiculopathy/myelopathy. |

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | Inflammatory back pain, morning stiffness, sacroiliitis. More common in younger males. HLA-B27 positive. |

| Vitamin B12 Deficiency (Subacute Combined Degeneration) | Posterior column and corticospinal tract dysfunction, paresthesias, gait ataxia, weakness. Low B12 levels. |

Prognosis and Long-Term Management

Spinal spondylosis is a chronic, progressive condition associated with aging. The prognosis varies widely depending on the severity of symptoms, the degree of neurological involvement, and the response to treatment. Many individuals with radiographic spondylosis remain asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms that can be managed conservatively. For those with symptomatic radiculopathy or myelopathy, treatment aims to alleviate pain and prevent further neurological decline. While surgery can be effective in decompressing neural structures and improving symptoms for many, some residual deficits may remain, and the underlying degenerative process continues. Long-term management often involves ongoing physical therapy, lifestyle modifications, and pain management strategies.

When to Consult a Spine Specialist

Consultation with a spine specialist (e.g., orthopedic spine surgeon, neurosurgeon, or physiatrist specializing in spine care) is recommended if an individual experiences:

- Persistent or worsening neck or back pain unresponsive to initial conservative measures.

- Radiating pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness in the arms or legs.

- Difficulty with balance, coordination, or walking (gait disturbance).

- Loss of fine motor skills in the hands.

- New onset of bladder or bowel dysfunction (urgency, incontinence).

- Symptoms suggestive of spinal cord compression (myelopathy).

Early evaluation can lead to an accurate diagnosis and the development of an appropriate treatment plan to manage symptoms and prevent progressive neurological impairment.

References

- Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. BMJ. 2007 Mar 10;334(7592):527-31.

- Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Kopjar B, et al. Efficacy and safety of surgical decompression in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: results of the AOSpine North America prospective multi-center study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Sep 18;95(18):1651-8.

- Tracy JA, Bartleson JD. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurologist. 2010 May;16(3):176-87.

- Nurick S. The pathogenesis of the spinal cord disorder associated with cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1972;95(1):87-100.

- Clarke E, Robinson PK. Cervical Spondylosis: A Factor in Myelopathy. Neurology. 1956 Jan;6(1):17-24.

- Naderi S, Ozgen S, Pamir MN, CANDAfi S, Acar F. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: surgical results and factors affecting the outcome. Neurosurgery. 2004 Jan;54(1):111-8; discussion 118-9.

- Young WF. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a common cause of spinal cord dysfunction in older persons. Am Fam Physician. 2000 Sep 1;62(5):1064-70, 1073.

- Boden SD, McCowin PR, Davis DO, Dina TS, Mark AS, Wiesel S. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Sep;72(8):1178-84.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome

MRI classification/Physiologic alignment.webp)

MRI classification/Disc pathology, canal narrowing, no cord impingment.webp)

MRI classification/Spondylosis, anterior cord impingement.webp)

MRI classification/Spondylosis, restricted motion, anterior or posterior impingement.webp)

MRI classification/Cervical spondylotic myelopathy, anterior and -or posterior impingement.webp)