Anatomy of the spine

- Introduction to Spinal Anatomy and Disease Prevention

- Regions of the Human Spine (Vertebral Column)

- General Structure of the Spine

- Spinal Stability and Movement

- The Spinal Cord and Nerves

- Key Anatomical Features by Spinal Region (Comparative Table)

- Common Spinal Pathologies Related to Anatomy

- Maintaining Spinal Health and Preventing Injury

- Further Resources

- References

Introduction to Spinal Anatomy and Disease Prevention

Understanding the intricate anatomy of the human spine is fundamental to appreciating its vital functions and the best ways to prevent diseases and injuries affecting the vertebral column. Knowledge of its structure, combined with practices that avoid physical overload and trauma, forms the cornerstone of spinal health.

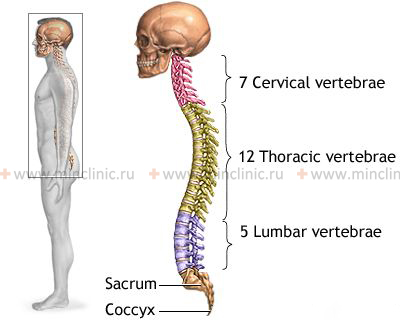

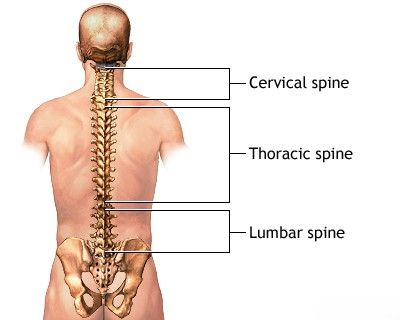

Regions of the Human Spine (Vertebral Column)

The human spine, or vertebral column, is a complex, segmented structure providing support, flexibility, and protection for the spinal cord. It is divided into several distinct regions based on the location and characteristics of the vertebrae:

- Cervical Spine (Neck): Composed of 7 cervical vertebrae (C1-C7). This region is highly mobile, allowing for a wide range of head movements. The lower segments (C5, C6, C7) are particularly mobile and thus susceptible to wear and injury. The first two cervical vertebrae, the atlas (C1) and axis (C2), have unique anatomy to support the skull and allow for rotational head movements.

- Thoracic Spine (Upper and Mid Back): Formed by 12 thoracic vertebrae (T1-T12). Each thoracic vertebra articulates with a pair of ribs, contributing to the structure of the rib cage. This region is less mobile than the cervical or lumbar spine due to the rib attachments, providing stability and protection for thoracic organs.

- Lumbar Spine (Lower Back): Consists of 5 lumbar vertebrae (L1-L5). These are the largest and strongest vertebrae, designed to bear significant body weight. The lower lumbar segments (L4, L5) and the lumbosacral junction (L5-S1) are the most mobile parts of the lumbar spine and are common sites for degenerative changes and injuries.

- Sacrum: This is a triangular bone formed by the fusion of 5 sacral vertebrae (S1-S5) into a single, solid structure known as the sacral bone (os sacrum). It articulates with the iliac bones of the pelvis at the sacroiliac joints, forming the posterior part of the pelvic girdle.

- Coccyx (Tailbone): Typically composed of 2 to 5 (commonly 4) small, fused coccygeal vertebrae. It is the terminal segment of the vertebral column. The coccyx can exhibit some mobility, particularly in women, which is thought to be related to its role during childbirth.

General Structure of the Spine

The anatomy of the spine can be broadly divided into anterior and posterior components, each with specific structures and functions.

Anterior Spinal Column: Vertebral Bodies and Intervertebral Discs

The anterior part of the spine is primarily composed of the cylindrical vertebral bodies. Each vertebral body is connected to the adjacent ones above and below by an intervertebral disc, which acts as a shock absorber and allows for movement. Exceptions to this are the unique articulation between the first (C1, atlas) and second (C2, axis) cervical vertebrae, which lacks a typical disc, and the naturally fused vertebrae of the sacrum and coccyx. The vertebral bodies are reinforced by strong ligaments: the anterior longitudinal ligament runs down the front surface, and the posterior longitudinal ligament runs down the back surface (within the spinal canal).

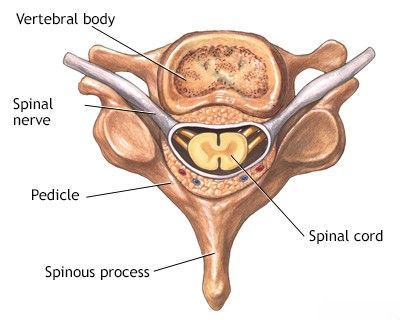

The anterior longitudinal ligament is robust and tightly adhered to both the intervertebral discs and the vertebral bodies. In contrast, the posterior longitudinal ligament is relatively weaker and less firmly attached, particularly laterally. This anatomical weakness contributes to the common tendency for intervertebral disc prolapse or herniation (squeezing out of the disc's contents, such as the nucleus pulposus) to occur in a posterior or posterolateral direction. Such herniations can protrude into the lumen of the spinal canal, potentially causing compression of the spinal cord or the nerve roots exiting from it.

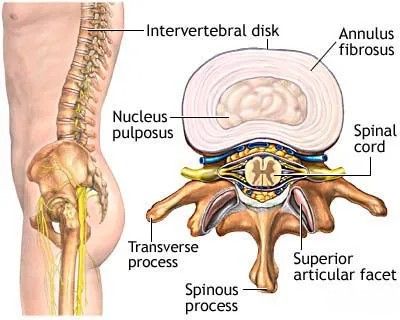

Posterior Spinal Elements: Arches, Processes, and Facet Joints

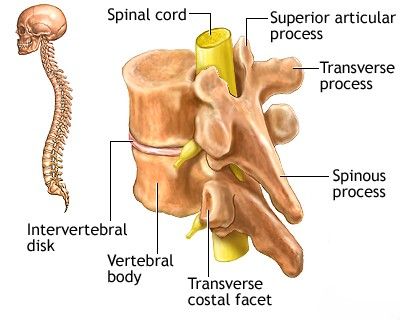

The posterior (back) part of each vertebra is formed by bony structures that extend backward from the vertebral body. These include the pedicles (short, stout processes that connect the vertebral arch to the body) and the laminae, which fuse posteriorly to form the vertebral arch (neural arch). This arch, along with the posterior surface of the vertebral body and the posterior longitudinal ligament, encloses the vertebral foramen. The succession of vertebral foramina forms the vertebral (spinal) canal, which houses and protects the spinal cord and its nerve roots. The ligamentum flavum (yellow ligament) connects the laminae of adjacent vertebrae.

The posterior parts of the vertebrae also articulate with adjacent vertebrae through paired intervertebral (facet or zygapophyseal) joints. Each vertebra has two superior and two inferior articular processes, which form these synovial joints. The facet joints have small articular surfaces, which are most pronounced in the lumbar spine, and they guide and limit the range of motion between vertebrae, contributing to the overall mobility of the spine.

Projecting posteriorly from each vertebral arch is a spinous process, and laterally from the junction of the pedicles and laminae are two transverse processes. These strong bony processes serve as attachment sites for ligaments and the tendons of back muscles, which are crucial for moving, supporting, and protecting the spinal column.

The Intervertebral Disc: Annulus Fibrosus and Nucleus Pulposus

The intervertebral disc is a complex structure crucial for spinal flexibility and shock absorption. It consists of two main parts:

- Nucleus Pulposus: The gelatinous, hydrophilic (water-loving) central portion of the disc. It is considered a remnant of embryonic notochordal tissue. It acts like a ball bearing, allowing movement and distributing pressure.

- Annulus Fibrosus: A tough outer ring composed of concentric layers of fibrocartilaginous and connective tissue fibers (lamellae). It surrounds and contains the nucleus pulposus, providing tensile strength to the disc.

After the completion of spinal development (typically around 24–26 years of age), the intervertebral discs largely lose their direct blood supply and rely on diffusion from adjacent vertebral endplates for nutrition. Over time, with aging and wear-and-tear, the discs tend to dehydrate, becoming less elastic and less efficient at shock absorption. These degenerative changes can lead to various spinal disorders, particularly in the most mobile segments of the spine: the cervical and lumbar regions.

Spinal Stability and Movement

Ligamentous and Muscular Support

The stability of the human spine is maintained by several key structures:

- Articulations of the vertebral bodies via the intervertebral discs.

- Intervertebral (facet) joints.

- An extensive network of ligaments (e.g., anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments, ligamentum flavum, interspinous, supraspinous, and intertransverse ligaments).

- Muscles of the back, abdomen, and pelvis.

The ligamentous apparatus of the spine possesses considerable strength to resist displacement. However, the vertebral bodies with their intervertebral discs do not inherently have the same overall strength as the ligaments to withstand displacement forces acting on the spinal column during various movements. This relative weakness is compensated for by the voluntary and reflex contractions of the paraspinal muscles (e.g., sacrospinalis/erector spinae), abdominal muscles, gluteal muscles, quadratus lumborum, and hamstring muscles, all of which contribute significantly to spinal stability and control.

Regional Mobility

The lumbar and cervical regions of the spine exhibit the greatest freedom of movement. In comparison, the thoracic spine is more rigidly fixed due to its articulation with the ribs and chest cage. This higher mobility in the neck and lower back makes these regions more susceptible to frequent injury and degenerative changes. In addition to voluntary movements that facilitate flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation of the trunk, many spinal movements are reflex-driven, ensuring the maintenance of body posture and balance, for example, during activities like walking or running.

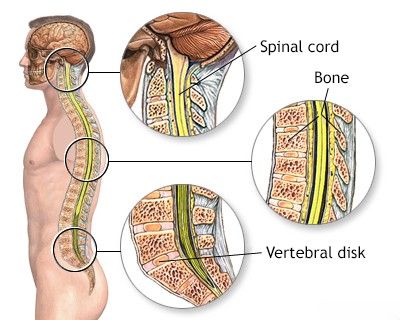

The Spinal Cord and Nerves

Location and Development

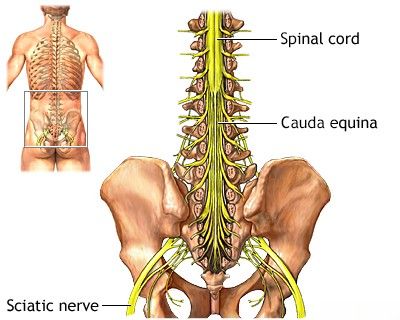

The spinal cord, a vital part of the central nervous system, is located within the protective lumen of the vertebral (spinal) canal. In a young child, the spinal cord fills the canal almost completely down to its lower end. However, as a person grows, the bony vertebral column grows faster and longer than the nervous tissue of the spinal cord. Consequently, in adulthood, the conus medullaris (the tapered lower end of the spinal cord) typically terminates at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebra (L1 or L2). Below this level, the spinal canal contains the cauda equina ("horse's tail"), a bundle of lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal nerve roots that descend to exit at their respective vertebral levels.

Epidural fatty tissue and a rich venous plexus surround the dural sac (the outermost covering of the spinal cord). Infection or inflammation of this epidural tissue can lead to conditions such as spinal epidural abscess or purulent spinal epiduritis.

Spinal anatomy: Illustrating the lumbar vertebrae, the termination of the spinal cord into the cauda equina, and the emergence of major nerves like the sciatic nerve.

Innervation of Spinal Structures

The various structures of the spine are innervated by recurrent meningeal branches (sinuvertebral nerves) of the spinal nerves. Pain-sensitive nerve endings and fibers from these nerves are found in the ligaments, muscles, periosteum of the vertebral processes, the outer layers of the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc, and the synovium of the intervertebral (facet) joints. Sensory fibers from these spinal structures, as well as from the sacroiliac and lumbosacral joints, converge to form the sinuvertebral nerves of Luschka. These nerves re-enter the spinal canal through the intervertebral foramina and convey sensory information (including pain) to the gray matter of the corresponding segments of the spinal cord, typically at the S1 and L1-L5 levels. Motor fibers emerge from these same spinal cord segments and travel within the spinal nerves to reach and innervate the muscles responsible for spinal movement and stability.

Key Anatomical Features by Spinal Region (Comparative Table)

| Feature | Cervical Spine (C1-C7) | Thoracic Spine (T1-T12) | Lumbar Spine (L1-L5) | Sacrum (S1-S5 Fused) | Coccyx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Vertebrae | 7 | 12 | 5 | 5 (fused) | 2-5 (fused) |

| Size of Vertebral Bodies | Small | Medium, heart-shaped | Large, kidney-shaped | Fused into large triangular bone | Very small, rudimentary |

| Mobility | Very high (most mobile) | Limited (due to ribs) | High | Immobile (fused, sacroiliac joints have minimal movement) | Slightly mobile (especially in females) |

| Spinous Processes | Short, often bifid (C2-C6) | Long, slender, point downwards | Short, thick, quadrangular | Fused to form median sacral crest | Rudimentary or absent |

| Transverse Processes | Have transverse foramina (for vertebral artery) | Have costal facets for rib articulation | Large, prominent | Fused to form lateral masses | Rudimentary |

| Primary Curvature | Lordosis (secondary curve) | Kyphosis (primary curve) | Lordosis (secondary curve) | Kyphosis (primary curve) | Anterior curve |

| Key Functions | Support head, allow wide range of motion | Support rib cage, protect thoracic organs | Bear body weight, allow trunk movement | Transmit weight to pelvis, form posterior pelvic wall | Attachment for some pelvic floor muscles/ligaments |

Common Spinal Pathologies Related to Anatomy

Understanding spinal anatomy is crucial for comprehending common spinal disorders:

- Intervertebral Disc Herniation/Protrusion: Weakness in the annulus fibrosus (often posterolaterally) allows the nucleus pulposus to bulge or extrude, potentially compressing nerve roots or the spinal cord. Most common in lumbar (L4-L5, L5-S1) and cervical (C5-C6, C6-C7) regions due to higher mobility and load.

- Spinal Stenosis: Narrowing of the spinal canal or intervertebral foramina, often due to degenerative changes (e.g., disc bulging, facet joint hypertrophy, ligamentum flavum thickening), leading to compression of neural elements.

- Spondylosis (Degenerative Disc Disease): Age-related changes in the intervertebral discs and facet joints, leading to pain, stiffness, and sometimes nerve compression.

- Spondylolisthesis: Forward slippage of one vertebra over another, often due to defects in the pars interarticularis (spondylolysis) or degenerative facet joint changes.

- Facet Joint Arthropathy: Degeneration and inflammation of the facet joints, a common cause of back pain.

- Spinal Fractures: Can result from trauma or osteoporosis, affecting vertebral bodies or posterior elements.

- Scoliosis/Kyphosis/Lordosis Abnormalities: Abnormal curvatures of the spine.

Maintaining Spinal Health and Preventing Injury

Preventing spinal diseases and injuries involves:

- Maintaining Good Posture: While sitting, standing, and lifting.

- Regular Exercise: Strengthening core muscles (abdominal and back muscles) provides better support for the spine. Flexibility exercises are also important.

- Proper Lifting Techniques: Using leg muscles instead of back muscles to lift heavy objects.

- Healthy Weight Management: Excess body weight puts additional stress on the spine.

- Ergonomics: Ensuring work and home environments are set up to minimize spinal strain.

- Avoiding Prolonged Static Postures: Taking regular breaks to move and stretch if sitting or standing for long periods.

- Adequate Nutrition: Including calcium and vitamin D for bone health.

- Avoiding Smoking: Smoking can impair blood supply to discs and accelerate degeneration.

Further Resources

We suggest that you familiarize yourself with some useful articles and links related to the work of our clinic and general medical knowledge:

- Glossary - Provides a list of the most common medical terms.

- A dictionary of neurological signs - Describes neurological signs and their significance.

- Frequently Asked Questions - Lists the most frequently asked questions by patients.

- Anatomy of the nervous system - Presents basic data on the structure of the brain, spinal cord, and nerves, with illustrations.

- Rules for preparing - Guidelines for patient preparation for certain diagnostic procedures.

- Nursing rules - Presents methods for safely caring for bedridden or debilitated patients at home or in a hospital setting.

References

- Gray H. Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 42nd ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017.

- Netter FH. Atlas of Human Anatomy. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Bogduk N. Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum. 5th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2012.

- White AA, Panjabi MM. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1990.

- Standring S, ed. Gray's Anatomy for Students. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Cramer GD, Darby SA. Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and ANS. 3rd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2014.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome