Scoliosis, poor posture

- Understanding Scoliosis, Stoop, and Poor Posture

- Diagnosis of Scoliosis, Stooping, and Impaired Posture

- Treatment of Scoliosis, Stooping, and Impaired Posture

- Differential Diagnosis of Spinal Curvatures

- Complications of Untreated Scoliosis and Severe Poor Posture

- Prevention and Early Detection

- When to Consult a Specialist

- References

Understanding Scoliosis, Stoop, and Poor Posture

Defining Scoliosis

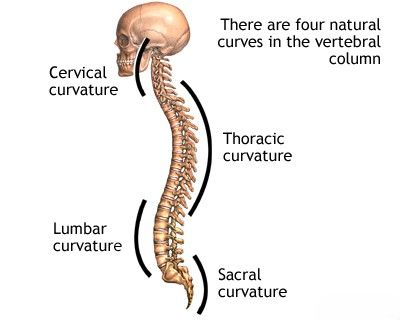

Scoliosis is defined as an abnormal lateral (sideways) curvature of the spine, often described as an arcuate deviation of the spinal axis in the frontal plane (i.e., curving to the right or left). This lateral curvature is often accompanied by a rotational component, where the vertebrae twist around their vertical axis. Scoliosis can range from mild to severe and may affect different regions of the spine.

Etiology of Scoliosis

The origin of scoliosis can be varied:

- Idiopathic Scoliosis: This is the most common type, accounting for approximately 80% of cases. The term "idiopathic" means the exact cause is unknown. It typically appears in late childhood or adolescence and is further classified by age of onset (infantile, juvenile, adolescent).

- Congenital Scoliosis: Results from malformations of the vertebrae present at birth, such as hemivertebrae (incompletely formed vertebrae), wedge vertebrae, or failure of segmentation (unseparated vertebrae).

- Neuromuscular Scoliosis: Develops secondary to underlying neurological or muscular diseases that affect spinal stability and muscle balance, such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida, or spinal cord injuries.

- Syndromic Scoliosis: Occurs as part of certain genetic syndromes, like Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or neurofibromatosis.

- Degenerative Scoliosis (De Novo Scoliosis): Develops in adults due to age-related wear and tear on the spinal discs and facet joints, leading to instability and asymmetric collapse.

- Functional or Non-structural Scoliosis: A temporary curve caused by an underlying issue outside the spine, such as a leg length discrepancy or muscle spasm. This type of curve typically corrects when the underlying problem is resolved.

- Antalgic Scoliosis: A reflex curvature adopted by the spine to alleviate pain, for example, from a herniated disc or other painful spinal condition.

- Psychological Factors (Rarely a direct cause of structural scoliosis): While severe emotional trauma in a child at school or psychological distress might influence posture, it is not typically considered a primary cause of structural scoliosis. However, poor posture can sometimes be mistaken for or exacerbate mild scoliosis.

Scoliosis can also be found in association with various diseases of the musculoskeletal system, other nervous system disorders, and diffuse lesions of connective tissue.

Classification of Scoliosis by Location and Severity

Depending on the location of the apex (the most deviated point) of the spinal curvature, scoliosis can be classified as:

- Upper-thoracic scoliosis

- Thoracic scoliosis (the most common type)

- Thoracolumbar scoliosis (apex at the junction of thoracic and lumbar spine)

- Lumbar scoliosis

- Combined scoliosis (typically an S-shaped curve with two primary apices, e.g., right thoracic and left lumbar).

The severity of scoliosis is determined by measuring the angle of curvature (Cobb angle) on a standing X-ray of the spine. Degrees of scoliosis are generally distinguished as follows:

- Scoliosis of the I degree (Mild): Cobb angle of 5°-10° (or sometimes up to 20-25° in other classifications).

- Scoliosis of the II degree (Moderate): Cobb angle of 11°-30° (or 25°-40/50°).

- Scoliosis of the III degree (Severe): Cobb angle of 31°-60° (or >40/50°).

- Scoliosis of the IV degree (Very Severe): Cobb angle from 61° and more.

(Note: Specific degree classifications can vary slightly between different schools of thought or classification systems. The Cobb angle measurement itself is standardized.)

The degree of curvature (deformation) in scoliosis is precisely determined by analyzing radiographic images of the spine taken in a direct (anteroposterior or posteroanterior) projection while the patient is standing.

Understanding Poor Posture and Stooping (Kyphosis)

While scoliosis refers to lateral curvature, "poor posture" is a broader term that can include various deviations from ideal spinal alignment. "Stooping" often refers to an increased thoracic kyphosis (hyperkyphosis), which is an excessive forward rounding of the upper back. This can be:

- Postural Kyphosis: Flexible, often due to habit or muscle weakness, and can be corrected voluntarily.

- Structural Kyphosis: A fixed deformity that cannot be fully corrected by postural changes. Causes include Scheuermann's disease (juvenile osteochondrosis of the spine), congenital vertebral anomalies, osteoporosis with vertebral compression fractures, or ankylosing spondylitis.

Poor posture can lead to muscle imbalances, pain, and reduced respiratory function if severe.

Diagnosis of Scoliosis, Stooping, and Impaired Posture

The diagnosis of scoliosis, stooping (hyperkyphosis), and other forms of impaired posture involves a combination of clinical examination and imaging studies. Early detection, especially for progressive scoliosis in children and adolescents, is crucial for effective management.

- Clinical Examination (Orthopedic Examination):

- Visual Inspection: The patient is observed from the back, front, and sides while standing upright and during movement. Signs to look for include:

- Asymmetry of shoulders (one shoulder higher than the other).

- Uneven waistline or hip height.

- Prominence of one scapula (shoulder blade).

- Visible lateral curvature of the spine.

- Head not centered over the pelvis.

- Increased or decreased normal spinal curves (kyphosis, lordosis).

- Adam's Forward Bend Test: This is a key screening test for scoliosis. The patient bends forward at the waist with arms hanging freely and knees straight. The examiner looks for asymmetry in the rib cage (rib hump) or lumbar prominence on one side, which indicates vertebral rotation associated with scoliosis.

- Range of Motion Assessment: Spinal flexibility and range of motion are evaluated.

- Neurological Examination: To rule out underlying neuromuscular causes (checking reflexes, muscle strength, sensation).

- Leg Length Measurement: To identify any significant leg length discrepancy that might cause functional scoliosis.

- Plumb Line Test: To assess spinal balance.

- Visual Inspection: The patient is observed from the back, front, and sides while standing upright and during movement. Signs to look for include:

- Radiography (X-rays):

- Standing Full-Length Spine X-rays: Anteroposterior (AP or PA) and lateral views are standard for diagnosing and quantifying scoliosis and kyphosis. The Cobb angle is measured on the AP/PA view to determine the magnitude of the scoliotic curve. Lateral views assess kyphosis and lordosis.

- Bending X-rays (Side Bending or Traction Films): May be used to assess the flexibility of the curve, which can help in surgical planning.

- Skeletal Maturity Assessment: X-rays of the hand/wrist (Greulich and Pyle method) or iliac crest (Risser sign) are used to determine the child's remaining growth potential, which is a critical factor in predicting curve progression and guiding treatment.

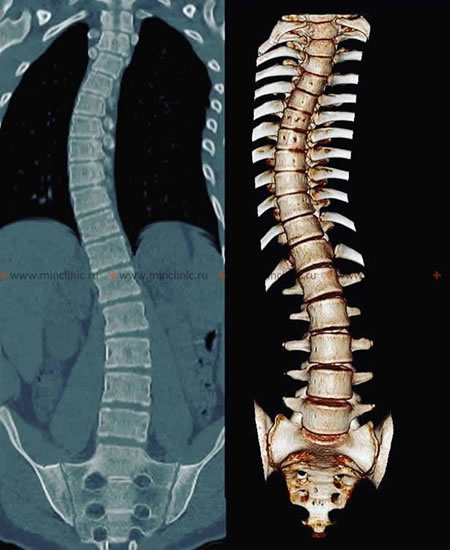

- Computed Tomography (CT) of the Spine: CT scans provide detailed images of the bony anatomy and are particularly useful for evaluating complex congenital scoliosis, assessing vertebral rotation, or for pre-surgical planning in some cases.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Spine: MRI is indicated if there are neurological symptoms, atypical curve patterns (e.g., left thoracic curve), rapid progression, or suspicion of underlying intraspinal pathology such as syringomyelia, tethered cord, or spinal tumors.

Diagnosing and managing childhood scoliosis and significant postural issues like stooping often require patience from both the child and their parents, as treatment can be long-term.

Idiopathic scoliosis of the spine is typically diagnosed and its severity quantified using standing radiography (X-rays), which allows for measurement of the Cobb angle.

Idiopathic scoliosis can also be visualized and assessed in detail using computed tomography (CT) of the spine, especially for complex cases or pre-surgical planning. This image shows a 3D reconstruction of scoliotic deformity.

Treatment of Scoliosis, Stooping, and Impaired Posture

The treatment approach for scoliosis, stooping, and other postural impairments depends on several factors, including the underlying cause, the severity of the curvature or postural deviation, the patient's age and remaining growth potential, and the presence of symptoms or risk of progression.

General Principles and Conservative Management

For mild scoliosis (e.g., curves <20-25 degrees in growing individuals), postural kyphosis, or general poor posture, conservative management is often the first line of treatment:

- Observation: Regular monitoring by a specialist (e.g., every 4-6 months) with clinical examination and sometimes repeat X-rays to check for curve progression, especially in growing children with idiopathic scoliosis.

- Physiotherapy and Specific Exercises: A tailored exercise program is crucial. This may include:

- Scoliosis-specific exercises (e.g., Schroth method, SEAS - Scientific Exercises Approach to Scoliosis) aimed at improving posture, muscle balance, core strength, and potentially reducing curve progression or improving cosmetic appearance.

- Exercises to strengthen back and core muscles, stretch tight muscles, and improve postural awareness.

- Breathing exercises to improve respiratory function if compromised.

- Massage Therapy: Can help relieve muscle tension and pain associated with postural strain or scoliosis.

- Manual Therapy: Techniques performed by qualified therapists (e.g., physiotherapists, chiropractors with expertise in scoliosis) may aim to improve spinal mobility and reduce muscle imbalances, potentially relieving excessive spinal deformation.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Encouraging good posture during daily activities (sitting, standing, carrying bags), ergonomic adjustments at school or work.

Bracing (Corsets)

For moderate idiopathic scoliosis in growing children (typically curves between 25 and 40-45 degrees with significant remaining growth), bracing may be recommended to try to halt or slow down curve progression. The goal of bracing is to prevent the curve from worsening to a point where surgery might be needed.

- Various types of braces (corsets) are available (e.g., Boston brace, Milwaukee brace, Wilmington brace, Charleston bending brace, newer dynamic braces).

- Braces are custom-fitted and typically need to be worn for a significant number of hours per day (e.g., 16-23 hours) until skeletal maturity is reached.

- Compliance with brace wear is critical for its effectiveness.

- Wearing a special corset can help to slightly reduce excessive spinal deformation and relieve strain on back muscles by providing external support.

Wearing a specialized brace (corset) is a common conservative treatment for progressive idiopathic scoliosis in growing individuals, aimed at correcting spinal curvature and improving impaired posture.

Surgical Intervention

Surgery is generally considered for severe scoliosis (e.g., curves >45-50 degrees in growing individuals or >50-55 degrees in skeletally mature individuals), or for curves that are progressing rapidly despite bracing, or if there is significant pain, neurological compromise, or respiratory issues.

- Spinal Fusion with Instrumentation: This is the most common surgical procedure for scoliosis. It involves correcting the spinal curvature as much as safely possible and then fusing the involved vertebrae together using bone grafts (autograft from the patient, or allograft from a donor) and instrumentation (rods, screws, hooks, or wires) to hold the spine in the corrected position while the fusion heals.

- Growing Rods or Expandable Systems: For young children with severe scoliosis and significant remaining growth, techniques like growing rods (which are periodically lengthened surgically) or magnetically controlled growing rods (MCGR) may be used to allow for continued spinal growth while controlling the curve.

- Vertebral Body Tethering (VBT): A newer, less invasive surgical option for certain types of idiopathic scoliosis in growing patients, aiming to modulate growth and correct the curve without fusion.

The decision for surgery is complex and involves careful consideration of the risks and benefits.

Differential Diagnosis of Spinal Curvatures

When evaluating spinal curvature, it's important to differentiate between various types and causes:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Idiopathic Scoliosis | Lateral curvature with rotation, no known underlying cause. Classified by age of onset (infantile, juvenile, adolescent). Diagnosis by exclusion. |

| Congenital Scoliosis | Present at birth due to vertebral malformations (hemivertebrae, wedge vertebrae, unsegmented bars). Often associated with other congenital anomalies. Early onset, can be rapidly progressive. |

| Neuromuscular Scoliosis | Associated with underlying neurological (e.g., cerebral palsy, spinal muscular atrophy, syringomyelia) or muscular (e.g., muscular dystrophy) conditions. Often long, sweeping C-shaped curves, pelvic obliquity common. |

| Postural Kyphosis (Stooping) | Flexible, exaggerated thoracic curve, often related to poor habits or muscle weakness. Corrects with active posture change. No structural vertebral changes. |

| Scheuermann's Kyphosis (Scheuermann-Mau Disease) | Structural, rigid thoracic hyperkyphosis in adolescents. Characterized by vertebral wedging (>5° in ≥3 adjacent vertebrae), endplate irregularities, Schmorl's nodes. Often associated with back pain. |

| Functional Scoliosis (Non-structural) | Lateral curve without vertebral rotation, often due to leg length discrepancy, pelvic obliquity from hip contracture, or antalgic (pain-related) posture. Curve disappears when underlying cause is corrected or patient lies down. |

| Spinal Tumors or Infections | Can cause painful scoliosis or kyphosis. Often associated with night pain, neurological symptoms, or systemic signs. Requires imaging (MRI, CT) and potentially biopsy. |

Complications of Untreated Scoliosis and Severe Poor Posture

If scoliosis is progressive or severe, or if significant postural kyphosis is left unmanaged, several complications can arise:

- Chronic Back Pain: Due to muscle imbalance, joint strain, and degenerative changes.

- Reduced Respiratory Function: Severe thoracic scoliosis or kyphosis can restrict lung expansion, leading to decreased lung capacity and shortness of breath, especially with exertion.

- Cardiopulmonary Problems (Rare, in very severe curves): In extreme cases (>100 degrees), severe thoracic deformity can affect heart and lung function more significantly.

- Neurological Complications (Uncommon with idiopathic scoliosis): Nerve root compression or spinal cord issues are more common with congenital or neuromuscular scoliosis, or if there's associated intraspinal pathology.

- Degenerative Spinal Changes: Increased wear and tear on intervertebral discs and facet joints, leading to premature osteoarthritis of the spine.

- Cosmetic Concerns and Psychological Impact: Visible deformity can affect self-esteem, body image, and social interactions, particularly in adolescents.

- Functional Limitations: Difficulty with certain physical activities or daily tasks.

Prevention and Early Detection

While most idiopathic scoliosis cannot be prevented, early detection is key to effective management and preventing severe progression.

- School Screening Programs: Historically common, involving visual inspection and Adam's forward bend test to identify children with potential scoliosis.

- Regular Pediatric Check-ups: Include spinal examination.

- Parental Awareness: Parents should be aware of signs like uneven shoulders, waist, or hip prominence.

- Promoting Good Posture: Encouraging good postural habits from a young age, ergonomic school furniture, and appropriate backpack use can help prevent non-structural postural problems.

- Regular Physical Activity: Maintaining good muscle strength and flexibility supports spinal health.

When to Consult a Specialist

Consultation with an orthopedic surgeon, spine specialist, or a physician experienced in scoliosis management is recommended if:

- Scoliosis or significant postural abnormality is suspected by parents, school screening, or a primary care physician.

- There is visible asymmetry of the back, shoulders, or hips.

- The child complains of persistent back pain associated with spinal curvature.

- There is a family history of scoliosis.

- Rapid worsening of a known curve is observed.

- Postural issues do not improve with simple measures or cause concern.

Early evaluation allows for accurate diagnosis, assessment of progression risk, and timely initiation of appropriate treatment if needed.

References

- Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Wright JG, Dobbs MB. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 17;369(16):1512-21.

- Horne JP, Flannery R, Usman S. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Feb 1;89(3):193-8.

- Negrini S, Donzelli S, Aulisa AG, et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018 Jan 10;13:3.

- Cobb JR. Outline for the study of scoliosis. Instr Course Lect. 1948;5:261-275. (Original description of Cobb angle measurement)

- Lonstein JE, Carlson JM. The prediction of curve progression in untreated idiopathic scoliosis during growth. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984 Sep;66(7):1061-71.

- Scoliosis Research Society (SRS). Website and Patient Information. (Refer to SRS for current guidelines and information)

- Scheuermann HW. Kyphosis dorsalis juvenilis. Ugeskr Laeger. 1920;82:385-393. (Original description of Scheuermann's disease)

- Kuznia AL, Hernandez AK, Lee LU. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Common Questions and Answers. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Jan 1;101(1):19-23.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome