Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

Understanding Vertebral Hemangiomas (Spinal Angiomas)

Definition and Prevalence

Vertebral hemangiomas, also known as spinal angiomas, are the most common benign (non-cancerous) neoplasms (tumors) affecting the spine. They are vascular malformations composed of newly formed blood vessels (capillary, cavernous, or mixed types) within the vertebral body. As a rule, vertebral angiomas are asymptomatic and are often discovered incidentally during diagnostic imaging (MRI, CT, X-ray) performed for unrelated reasons, such as back pain, infection, or spinal injury. Spinal hemangiomas are most frequently found in the middle (thoracic) and lower (lumbar) regions of the spine.

Epidemiology of Vertebral Hemangiomas

Hemangiomas of the vertebrae are very common, occurring in approximately 10-12 percent of the population based on autopsy data and radiological studies. Most are detected on standard radiographs of the spine. Often, smaller hemangiomas may not be evident on plain X-rays and are only visualized with more advanced imaging modalities like CT or MRI, or are found during post-mortem examinations. Hemangiomas most often form in adults, typically between the ages of 30 and 50. For unknown reasons, the incidence of vertebral hemangiomas is slightly higher in women than in men, and they are most likely to become symptomatic (if they do) in the fourth decade of life.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the spine provides excellent visualization of the soft tissue and vascular components of a vertebral hemangioma, often showing characteristic signal patterns.

The Clinical Presentation of Vertebral Hemangiomas: Asymptomatic vs. Symptomatic

The vast majority of vertebral hemangiomas remain asymptomatic throughout an individual's life and are considered incidental findings. However, a small percentage (less than 1%) can become symptomatic. Pain is the most common symptom, and it can arise from several mechanisms:

- Vertebral Body Destruction or Expansion: Growth of the hemangioma can weaken the vertebral body, leading to microfractures or, rarely, a pathological compression fracture. Expansion of the vertebral body can also cause pain.

- Epidural Extension: The hemangioma can extend beyond the confines of the vertebral body into the epidural space, potentially compressing the spinal cord or nerve roots.

- Neural Foramen Involvement: Extension into the intervertebral foramen (the opening where nerve roots exit the spinal canal) can cause radicular pain.

Increased physical activity, exercise, or household stress can provoke or exacerbate pain, most often due to increased axial load on the vertebra affected by the tumor. Symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas are more common in women than in men. In the absence of timely treatment, symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas can, in rare cases, lead to serious neurological disorders.

Symptoms of Vertebral Hemangiomas

While most hemangiomas are asymptomatic, if symptoms do occur, they can manifest as:

- Localized Back Pain: Often dull, aching, and localized to the level of the affected vertebra. Pain may worsen with activity or weight-bearing.

- Radicular Pain: Pain radiating along the course of a nerve root (e.g., into an arm or leg) due to inflammation or compression of the nerve root by the hemangioma or a secondary fracture.

- Symptoms of Spinal Cord Compression (Myelopathy): If the hemangioma extends into the spinal canal and compresses the spinal cord. This can include weakness, numbness, tingling in the limbs, difficulty with balance and coordination, gait disturbance, and, in severe cases, bowel or bladder dysfunction. These are more common with "aggressive" hemangiomas.

Pathophysiology of Vertebral Hemangiomas

Vertebral hemangiomas consist of abnormal proliferations of blood vessels (capillary, cavernous, or mixed types) interspersed with fatty marrow and thickened bony trabeculae within the vertebral body. These vascular cavities, due to their volume and pressure effects, can cause displacement and resorption of the surrounding normal bone tissue. In rare instances, particularly with the capillary type of hemangioma, lytic (destructive) erosion of the vertebra towards the epidural space can be observed. Hemangiomas are generally slow-growing lesions, and as mentioned, most remain asymptomatic.

Most vertebral hemangiomas occur in the thoracic spine, but they can also be found in other parts of the spinal column, including the lumbar and, less commonly, the cervical spine.

Diagnosis of Vertebral Hemangiomas

The diagnosis of vertebral hemangiomas relies heavily on characteristic findings from various imaging modalities.

Radiographic Characteristics (X-ray)

If a hemangioma is suspected, or found incidentally, an X-ray of the spine may reveal a characteristic bone change within the vertebral body. This typically appears as a "corduroy cloth" or "jailhouse stripes" pattern due to the vertical striations created by thickened, prominent trabeculae within the cancellous (spongy) bone of the vertebral body. These trabeculae are essentially the reinforced lattice structures within the bone. While X-rays can suggest a hemangioma, they may not detect smaller lesions and offer limited detail regarding soft tissue extension.

Educational video: A CT scan of the spine is a valuable imaging technique that may be used to assess various spinal conditions, including vertebral hemangiomas, herniated discs, spinal stenosis, scoliosis, traumatic injuries, tumors, congenital structural problems like spina bifida, as well as vascular issues or infections affecting the spine.

Computed Tomography (CT) of Vertebral Hemangiomas

Computed tomography (CT) of the spine provides more detailed visualization of the bony architecture. On axial (cross-sectional) CT slices, vertebral hemangiomas typically exhibit a "polka-dot" or "salt-and-pepper" appearance. This pattern arises from the cross-sections of the thickened vertical trabeculae appearing as dense dots (sclerotic inclusions) within the less dense fatty or vascular marrow spaces, sometimes described as resembling "peas." If these characteristic changes are present, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine is often performed as the next diagnostic step to assess for any soft tissue extension of the tumor down the spine (e.g., into the epidural space of the spinal canal) or to evaluate for spinal cord or nerve root compression.

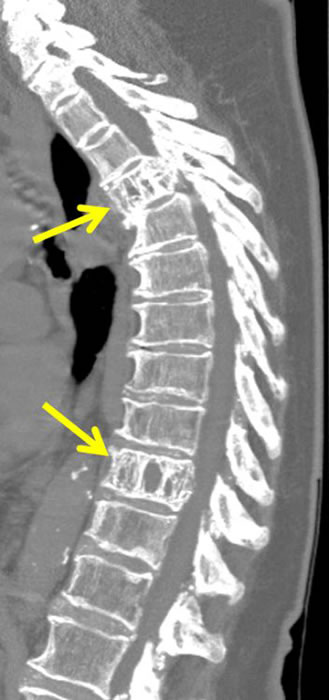

Computed tomography (CT) of the spine in a case of aggressive vertebral hemangioma typically shows pinpoint lesions of sclerosis, often described as "polka-dot" or "pea" blotches on transverse (axial) images of the vertebra (indicated by arrows).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of Vertebral Hemangiomas

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the spine is superior to CT for visualizing the soft tissue components of a hemangioma (such as its fat and water content) and any epidural extension or neural compression. The thickened trabeculae of the vertebral bodies within a hemangioma typically appear as areas of low signal intensity on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI sequences. The signal characteristics of the intervening marrow space depend on the composition of the hemangioma:

- T1-weighted mode: Hemangiomas often exhibit a high-intensity signal (appear bright) due to the presence of a significant fatty component within the lesion.

- T2-weighted mode: Hemangiomas usually show a bright or high-intensity signal (often even brighter than on T1-weighted images), reflecting their high water content due to vascularity and slow blood flow.

- T1-weighted mode with contrast (T1 C+): Significant enhancement is typically seen after gadolinium administration due to the high vascularity of the hemangioma.

- STIR (Short Tau Inversion Recovery) sequences: Fat-rich hemangiomas will show signal suppression, while more vascular or water-rich components will remain bright.

Differential Diagnosis from Malignant Metastases

A crucial aspect of diagnosing vertebral hemangiomas is differentiating them from malignant vertebral metastases (cancer spread to the spine from other organs and tissues). Metastases on MRI typically have a reduced signal intensity (appear dark) on T1-weighted images and an increased signal intensity (appear bright) on T2-weighted images, and they usually enhance avidly with contrast. However, unlike hemangiomas, metastases generally lack the characteristic thickened trabeculae seen in hemangiomas. An MRI of the spine can also clearly demonstrate the extent of any potential spinal nerve damage and is invaluable in planning surgical treatment for symptomatic or aggressive hemangiomas.

On MRI of the spine, vertebral hemangiomas can be differentiated from metastases of other malignant neoplasms by the characteristic presence of thickened bony trabeculae (indicated by arrows) within the affected vertebral bodies, a feature typically absent in metastatic lesions.

Aggressive Vertebral Hemangiomas

Unlike typical, asymptomatic vertebral hemangiomas, "aggressive" hemangiomas are a subset that exhibit more concerning features. These lesions can actively expand the vertebral body from within, invade paravertebral (adjacent to the spine) soft tissues, and, significantly, can extend into the spinal canal. This epidural extension can cause compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots, leading to neurological deficits. Aggressive hemangiomas may also cause pathological vertebral fractures due to weakening of the bone structure.

On MRI of the spine, aggressive hemangiomas may sometimes resemble metastatic tumors due to their expansile nature and soft tissue components. However, the presence of thickened trabeculae within the affected vertebral bodies, even if partially obscured by the aggressive features, remains a key imaging characteristic that helps differentiate aggressive hemangiomas from other malignant neoplasms.

Computed tomography (CT) of the spine is often more sensitive than MRI for clearly delineating the typical bone changes seen in aggressive hemangiomas. These include the "polka-dot" sign (pinpoint areas of sclerosis) on transverse (axial) images, and the characteristic vertical striations that look like "corduroy fabric," "lattice rods," or "honeycomb" patterns on sagittal or coronal reformatted images. These features reflect the underlying thickened bony trabeculae.

Computed tomography (CT) of the spine in cases of aggressive vertebral hemangioma typically demonstrates characteristic vertical lines on sagittal images (indicated by arrows), which can have the appearance of "corduroy fabric," "bars of a lattice," or "honeycomb" patterns.

Treatment of Vertebral Hemangiomas and Subsequent Prognosis

Indications for Treatment

Treatment for most incidentally discovered, asymptomatic vertebral hemangiomas is generally not required. Observation with periodic imaging may be considered for larger asymptomatic lesions or those with some concerning features. Treatment becomes necessary if the patient develops symptoms of neurological deficit (e.g., myelopathy or radiculopathy due to spinal cord or nerve root compression) or severe, intractable pain directly attributable to the hemangioma (e.g., from vertebral body expansion or pathological fracture).

Treatment Options

When symptoms necessitate intervention, several treatment options are available, often selected individually or in combination based on the clinical scenario, lesion characteristics, and patient factors:

Observation

For asymptomatic, stable lesions, continued observation with follow-up imaging may be appropriate.

Radiation Therapy

External beam radiation therapy can be effective in treating pain symptoms caused by vertebral hemangiomas, particularly those that are not causing neurological compression but are a source of significant pain. It works by reducing the vascularity and potentially promoting sclerosis of the tumor.

Percutaneous Ethanol Injection

Direct injection of ethanol (sclerotherapy) into the hemangioma under fluoroscopic or CT guidance can be effective for treating pain symptoms. Ethanol causes thrombosis and necrosis of the hemangioma tissue, leading to its subsequent scarring and shrinkage.

Vertebroplasty/Kyphoplasty (with bone cement)

These minimally invasive procedures involve injecting polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement into the affected vertebral body. This stabilizes the vertebra, can relieve pain (especially if related to microfractures or instability), and may also have some tumoricidal effect. Balloon kyphoplasty involves creating a cavity with a balloon before cement injection to potentially restore some vertebral height.

Intravascular Transarterial Embolization

This neuroradiological procedure involves selectively catheterizing the arteries supplying the hemangioma and injecting embolic material (e.g., particles, coils, glue) to block blood flow to the tumor. Embolization can be used as a standalone treatment to reduce pain or tumor size, or more commonly, as a preoperative adjunct to reduce intraoperative bleeding during surgical resection.

Surgical Resection (Laminectomy, Vertebrectomy)

Open surgical intervention is typically reserved for symptomatic hemangiomas causing significant neurological compression, progressive neurological deficits, spinal instability, or intractable pain unresponsive to less invasive measures. Surgical goals include decompression of neural elements and stabilization of the spine.

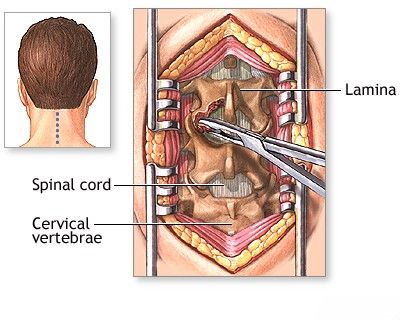

- Laminectomy: Removal of the vertebral lamina (posterior arch) to decompress the spinal canal if there is epidural extension of the hemangioma causing spinal cord or nerve root compression.

- Tumor Resection: Surgical removal (resection) of the hemangioma tissue from the affected vertebra. This can range from intralesional debulking to more complete en bloc resection.

- Vertebrectomy: Complete removal of the affected vertebra, followed by spinal reconstruction and fusion, may be necessary for very aggressive or destructive hemangiomas causing severe instability or compression.

Open surgery for vertebral hemangiomas can be associated with a risk of significant bleeding due to the vascular nature of these tumors, so meticulous surgical technique and often preoperative embolization are crucial.

A laminectomy is a surgical procedure performed to decompress the spinal canal in cases of symptomatic vertebral hemangioma that cause compression of the spinal cord and nerve roots.

Prognosis

The prognosis for asymptomatic vertebral hemangiomas is excellent, as most remain stable and never cause problems. For symptomatic hemangiomas, the prognosis after treatment is generally good, with most patients experiencing significant pain relief and improvement or stabilization of neurological function. However, the outcome depends on the severity of symptoms at presentation, the aggressiveness of the hemangioma, and the chosen treatment modality. Recurrence after treatment is uncommon but possible. Timely intervention with a combination of procedures, such as embolization followed by surgical removal and/or radiation therapy, can often achieve significant improvement in the patient's condition.

When to Consult a Spine Specialist

Consultation with a spine specialist (e.g., neurosurgeon or orthopedic spine surgeon) experienced in treating spinal tumors is recommended if:

- A vertebral hemangioma is found incidentally, especially if it is large or has atypical features on imaging.

- Back pain is persistent, severe, or localized to an area where a hemangioma is known to exist.

- Any neurological symptoms develop, such as radiating pain, numbness, weakness in the limbs, or bowel/bladder dysfunction.

- There is concern about an "aggressive" hemangioma based on imaging findings.

A specialist can accurately diagnose the condition, assess its clinical significance, and recommend the most appropriate management plan, whether it be observation or active treatment.

References

- Nguyen JP, Djindjian M, Gaston A, et al. Vertebral hemangiomas: presentation and management. Neurochirurgie. 1997;43(3):173-84.

- Pastushyn AI, Slinko EI, Mirzoyeva GM. Vertebral hemangiomas: diagnosis, management, natural history and clinicopathological correlates in 86 patients. Surg Neurol. 1998 Dec;50(6):535-47.

- Rodallec MH, Feydy A, Larousserie F, et al. Diagnostic imaging of solitary tumors of the spine: what to do and say. Radiographics. 2008 Jul-Aug;28(4):1019-41.

- Gaudino S, Martucci M, Colantonio R, et al. A systematic approach to vertebral hemangioma. Skeletal Radiol. 2015 Jan;44(1):25-36.

- Laredo JD, Assouline E, Gelbert F, Wybier M, Merland JJ. Vertebral hemangiomas: fat content as a sign of aggressiveness. Radiology. 1990 May;175(2):467-72.

- Belkoff SM, Mathis JM, Fenton DC, Scribner RM, Reiley ME, Talmadge K. An ex vivo biomechanical evaluation of a hydroxyapatite cement for use with kyphoplasty. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Jul 15;26(14):1537-41. (Context for vertebroplasty materials)

- Hadjipavlou AG, Tzermiadianos MN, Katonis PG, Szpalski M. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas. Joint Bone Spine. 2007 Oct;74(5):497-502.

- Jiang L, Liu XG, Yuan HS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of vertebral hemangiomas with neurologic deficit: a report of 29 cases. Spine J. 2014 Feb 1;14(2):270-9.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome