Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Understanding Ankylosing Spondylitis (Bechterew's Disease)

- Diagnosis of Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Treatment Goals and Comprehensive Management of Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Lifestyle Management and Patient Education (Regime)

- Pharmacological Therapies

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

- Glucocorticoids (Corticosteroids)

- Conventional Synthetic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (csDMARDs) - e.g., Sulfasalazine

- Targeted Synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) - JAK inhibitors

- Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (bDMARDs)

- Older Immunosuppressants (Historical Context)

- Muscle Relaxants for Spasticity

- Non-Pharmacological Therapies

- Patient Monitoring and Follow-up

- Surgical Intervention (Rarely)

- Differential Diagnosis of Inflammatory Back Pain

- Potential Complications of Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Prognosis and Living with Ankylosing Spondylitis

- When to Consult a Rheumatologist

- References

Understanding Ankylosing Spondylitis (Bechterew's Disease)

Definition and Key Features

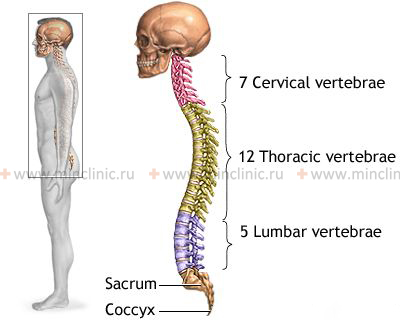

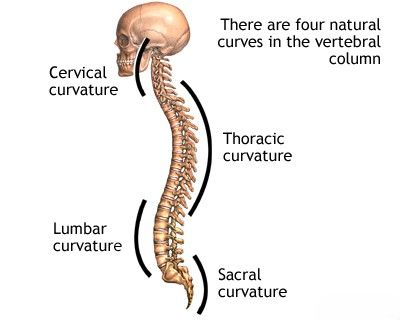

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), historically also known as Bechterew's disease or Marie Strümpell disease, is a chronic, systemic inflammatory condition primarily classified under the umbrella of spondyloarthritis. This disease predominantly targets the axial skeleton, which includes the sacroiliac (SI) joints (connecting the spine to the pelvis), the intervertebral joints, and the costovertebral joints (where ribs connect to the spine). Paravertebral tissues (soft tissues around the spine) are also commonly affected. A hallmark of AS is the progressive inflammation that can lead to new bone formation (syndesmophytes) bridging adjacent vertebrae, ultimately causing fusion (ankylosis) of these joints. This process results in increasing stiffness, a characteristic forward-stooped posture (thoracic kyphosis), and, in severe instances, a complete loss of spinal mobility, sometimes referred to as "bamboo spine" due to its appearance on X-rays. While the axial skeleton is the primary site, AS can also involve peripheral joints (such as hips, shoulders, and knees) and entheses, which are the sites where tendons and ligaments attach to bones.

Ankylosing spondylitis typically manifests in late adolescence or early adulthood, with the peak age of onset usually between 20 and 30 years. Although it has a higher prevalence and often demonstrates a more severe radiographic progression in males, women are also affected. In females, AS may present with different clinical features, such as more prominent peripheral joint involvement or less severe spinal changes visible on X-rays. Juvenile-onset ankylosing spondylitis can also occur, starting before the age of 16.

Educational video explaining Ankylosing Spondylitis, its symptoms, diagnosis, and management approaches.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The precise cause of ankylosing spondylitis remains unknown, but it is understood to be a complex multifactorial disease involving genetic predisposition, immune system dysregulation, and potential environmental triggers.

- Genetic Factors: A strong genetic link exists with the Human Leukocyte Antigen B27 (HLA-B27) gene. In Caucasian populations, over 90% of individuals with AS are positive for HLA-B27. However, it is important to note that only a small fraction (around 1-5%) of HLA-B27 positive individuals in the general population actually develop AS, indicating that HLA-B27 is a major susceptibility gene but not solely causative. Other genes related to immune function and inflammation (e.g., ERAP1, IL23R) have also been identified as contributing to AS risk.

- Immune Dysregulation: AS is considered an autoimmune or autoinflammatory condition. The immune system mistakenly targets the body's own tissues, particularly at entheseal sites and within the axial joints. Key inflammatory pathways and cytokines, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and the Interleukin-23/Interleukin-17 (IL-23/IL-17) axis, play pivotal roles in driving the chronic inflammation characteristic of AS.

- Environmental Triggers: While not definitively established, various environmental factors have been proposed as potential triggers in genetically susceptible individuals. These include certain bacterial infections (e.g., gut bacteria like *Klebsiella pneumoniae*, or urogenital infections with *Chlamydia trachomatis*) that might initiate or perpetuate the inflammatory response through mechanisms like molecular mimicry. Mechanical stress and biomechanical factors at entheseal sites may also contribute to local inflammation.

The pathogenesis of AS involves chronic inflammation primarily at the entheses. This enthesitis leads to erosion of bone at the insertion sites, followed by a process of repair that involves abnormal new bone formation (ossification). In the spine, this results in the formation of syndesmophytes, which are bony growths that bridge the intervertebral discs, eventually leading to fusion of the vertebral bodies and sacroiliac joints. This cycle of inflammation, tissue damage, and aberrant bone formation is central to the progressive stiffness and loss of mobility seen in AS.

Clinical Manifestations and Disease Course

The hallmark symptom of ankylosing spondylitis is **inflammatory back pain**. This type of back pain has specific characteristics that help differentiate it from mechanical back pain:

- Insidious Onset: The pain typically begins gradually, often before the age of 40-45.

- Improvement with Exercise: Pain and stiffness tend to improve with physical activity and movement.

- Worsening with Rest: Pain and stiffness are usually worse in the morning upon waking or after prolonged periods of inactivity (e.g., sitting for long durations). Morning stiffness often lasts for more than 30 minutes.

- Nocturnal Pain: Pain, particularly in the second half of the night, may awaken the patient from sleep.

- Alternating Buttock Pain: Pain that shifts from one buttock to the other is highly suggestive of sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints).

Other common musculoskeletal manifestations include:

- Spinal Stiffness and Reduced Mobility: Progressive loss of range of motion in the lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spine. This can affect daily activities such as bending, twisting, and looking overhead. Measurement of spinal mobility (e.g., Schober's test, chest expansion, cervical rotation) is part of clinical assessment.

- Peripheral Arthritis: Inflammation of joints in the limbs, occurring in about 30-50% of patients. It typically affects large joints like the hips and shoulders, but knees and ankles can also be involved. Peripheral arthritis in AS is often asymmetrical and oligoarticular (affecting few joints).

- Enthesitis: Inflammation at sites where tendons, ligaments, or joint capsules attach to bone. Common sites include the Achilles tendon insertion, plantar fascia insertion (causing heel pain), costosternal junctions, iliac crests, and spinous processes.

- Dactylitis ("sausage digits"): Diffuse swelling of an entire finger or toe due to inflammation of the joints and surrounding soft tissues.

AS is a systemic disease and can involve various **extra-articular manifestations**:

- Acute Anterior Uveitis (Iritis): The most common extra-articular feature, occurring in 25-40% of patients. It presents with eye pain, redness, photophobia (light sensitivity), and blurred vision. Recurrent episodes are common.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Clinical or subclinical Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis is found in a subset of AS patients.

- Psoriasis: Skin and nail psoriasis can be associated with spondyloarthritis.

- Cardiac Involvement (less common): May include aortitis (inflammation of the aorta), aortic valve regurgitation, and conduction abnormalities (e.g., heart block).

- Pulmonary Involvement (less common): Apical lung fibrosis (scarring at the lung apices) and restrictive lung disease due to reduced chest wall expansion from costovertebral joint fusion can occur in long-standing disease.

- Neurological Complications (rare but serious): Can result from spinal fractures (even with minor trauma in a rigid spine), atlantoaxial subluxation (instability between the first and second cervical vertebrae), or cauda equina syndrome (compression of nerve roots at the base of the spinal cord).

- Osteoporosis: Increased risk of low bone mineral density and vertebral fractures, even early in the disease course, due to chronic inflammation and immobility.

Systemic symptoms such as fatigue, low-grade fever, and unintended weight loss can also occur, particularly during periods of active disease.

The disease course of AS is highly variable. Some individuals experience mild symptoms with minimal progression, while others suffer from severe, progressive disease leading to significant disability and deformity. In advanced stages, patients may develop the characteristic "frozen" or fixed spine, often in a pronounced kyphotic (forward-flexed) posture, impacting posture, gait, and daily functioning.

Diagnosis of Ankylosing Spondylitis

The diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis is based on a combination of clinical features (particularly the presence of inflammatory back pain), imaging findings (especially sacroiliitis), and laboratory tests (primarily HLA-B27). Early diagnosis can be challenging as initial symptoms may be subtle or mimic other conditions, and radiographic changes may take years to become apparent. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) classification criteria are widely used for identifying patients with axial spondyloarthritis, which includes both AS (radiographic axial SpA) and non-radiographic axial SpA (nr-axSpA).

Key diagnostic components include:

- Clinical Evaluation:

- Detailed history focusing on the characteristics of back pain (inflammatory vs. mechanical), onset age, duration of symptoms, presence of peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, extra-articular manifestations (uveitis, IBD, psoriasis), and family history of AS or related conditions.

- Physical examination to assess spinal mobility (e.g., Schober's test for lumbar flexion, lateral spinal flexion, chest expansion, cervical rotation), sacroiliac joint tenderness, peripheral joint inflammation, and entheseal tenderness.

- Imaging Studies:

- Radiographs (X-rays) of the Sacroiliac Joints and Spine: X-rays are used to detect structural changes. Key findings include:

- Sacroiliitis: Erosion, sclerosis (increased bone density), joint space narrowing, and eventually ankylosis (fusion) of the sacroiliac joints. According to the modified New York criteria, definite radiographic sacroiliitis (bilateral grade ≥2 or unilateral grade ≥3-4) is required for a diagnosis of AS.

- Spinal Changes: Squaring of vertebral bodies, syndesmophytes (bony growths from the edges of vertebrae that can bridge intervertebral discs), ossification of spinal ligaments, and ultimately the "bamboo spine" appearance in advanced disease.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI of the sacroiliac joints and/or spine is much more sensitive than X-rays for detecting early inflammatory changes. It can reveal active sacroiliitis (bone marrow edema/osteitis) and spondylitis before structural damage is evident on X-rays. MRI is particularly useful in diagnosing nr-axSpA and assessing disease activity. Contrast enhancement (gadolinium) may be used.

- Ultrasound: High-resolution ultrasound with power Doppler can be useful for detecting and assessing inflammation in peripheral joints and entheses.

- Radiographs (X-rays) of the Sacroiliac Joints and Spine: X-rays are used to detect structural changes. Key findings include:

- Laboratory Tests:

- HLA-B27 Genetic Marker: While not diagnostic on its own (as many HLA-B27 positive individuals do not develop AS, and some AS patients are HLA-B27 negative), its presence is a strong susceptibility factor and supports the diagnosis in the context of appropriate clinical and imaging findings.

- Inflammatory Markers: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) are often elevated during active disease, reflecting systemic inflammation. However, they can be normal in a significant proportion of patients with active AS.

- Autoantibodies: There are no specific autoantibodies for AS (e.g., rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP antibodies are typically negative, helping to differentiate from rheumatoid arthritis).

The diagnosis is often made by a rheumatologist who integrates all these findings.

Treatment Goals and Comprehensive Management of Ankylosing Spondylitis

The management of ankylosing spondylitis is a long-term, multidisciplinary endeavor that aims to control symptoms, maintain function, prevent structural damage, and improve quality of life. The treatment program incorporates pharmacological therapies, non-pharmacological interventions, patient education, and regular monitoring. Active patient involvement and adherence to the treatment plan are crucial for optimal outcomes.

The primary goals of AS treatment are to:

- Reduce pain and stiffness.

- Suppress inflammation and reduce disease activity.

- Maintain or improve spinal mobility and physical function.

- Prevent or slow down structural damage and spinal fusion.

- Minimize extra-articular manifestations.

- Improve overall quality of life and participation in daily activities.

Lifestyle Management and Patient Education (Regime)

Patient education and lifestyle modifications are integral to managing AS:

- Patient Education: Understanding the disease, its potential course, treatment options, and the importance of adherence to therapy and exercise is critical. Patient support groups can also be beneficial.

- Regular Exercise Program: This is a cornerstone of AS management and should be lifelong. A physiotherapist specializing in AS can design a personalized program including:

- Spinal mobility exercises (flexion, extension, lateral flexion, rotation).

- Stretching exercises to maintain flexibility.

- Strengthening exercises for back, abdominal, and hip muscles.

- Postural exercises to counteract the tendency towards kyphosis.

- Deep breathing exercises to maintain chest expansion.

- Postural Awareness: Conscious effort to maintain good posture during daily activities (sitting, standing, walking) is essential.

- Sleeping Habits: Sleeping on a firm mattress, often supine (on the back) with a thin pillow or no pillow, is recommended to promote spinal alignment. Regular periods of lying prone (on the stomach) can help prevent flexion contractures of the hips and spine.

- Ergonomics: Modifying the work environment (e.g., chair, desk height) and taking frequent breaks to stretch and change position are important for individuals with sedentary jobs to avoid prolonged spinal flexion.

- Smoking Cessation: Smoking is strongly discouraged as it is associated with higher disease activity, more severe radiographic progression, and poorer response to treatment in AS. It also worsens respiratory function.

- Healthy Diet: While no specific diet cures AS, a balanced, anti-inflammatory diet may be beneficial for overall health. Maintaining a healthy weight is also important.

During acute flares with severe pain, short periods of rest may be needed, but complete immobilization should be avoided. Gentle range-of-motion exercises should be continued as tolerated, ideally under physiotherapy guidance, to prevent loss of function. Following intensive inpatient treatment for a flare, participation in a structured rehabilitation program or spa treatment can be beneficial. Continuous long-term monitoring by a rheumatologist is essential.

Pharmacological Therapies

Medications are used to control pain, inflammation, and disease activity, and in some cases, to modify the disease course.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are the first-line pharmacological treatment for AS, providing effective relief from pain and stiffness. Continuous use of NSAIDs, rather than on-demand use, may be more effective in controlling symptoms and has been suggested in some studies to potentially slow radiographic progression, although this is still debated. Examples include:

- Indomethacin (historically considered very effective for AS)

- Naproxen

- Diclofenac

- Ibuprofen

- COX-2 selective inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib, etoricoxib), which may offer a better gastrointestinal safety profile for long-term use in some patients.

The choice of NSAID is often individualized based on efficacy and tolerability. Long-term NSAID use requires monitoring for potential side effects, including gastrointestinal (ulcers, bleeding), renal (kidney impairment), and cardiovascular risks. Phenylbutazone (Butadione) and Reopirin (a combination product) mentioned in older texts carry significant risks of severe side effects (e.g., agranulocytosis) and are generally not used in modern practice due to the availability of safer alternatives.

A lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine in a patient with Bechterew's disease (ankylosing spondylitis) may demonstrate characteristic changes leading to a "frozen" or ankylosed appearance.

Glucocorticoids (Corticosteroids)

Systemic (oral or intravenous) glucocorticoids have a limited role in the long-term management of axial AS due to modest efficacy for spinal symptoms and significant potential for side effects with prolonged use. However, they may be considered in specific situations:

- Local Injections: Intra-articular injections for peripheral arthritis (e.g., hydrocortisone, triamcinolone/Kenalog) or local injections for enthesitis or sacroiliitis can be effective.

- Acute Flares: Short courses of oral prednisolone (e.g., 15–20 mg/day, tapered rapidly) may be used for severe flares of axial or peripheral disease if NSAIDs are insufficient.

- Uveitis: Topical corticosteroid eye drops are essential for acute anterior uveitis. Systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressants may be needed for severe or refractory uveitis.

- Pulse Intravenous Methylprednisolone: High-dose IV methylprednisolone (e.g., 1 gram daily for 3 days) is sometimes used for very severe, refractory disease activity or systemic manifestations, typically in a hospital setting.

Conventional Synthetic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (csDMARDs) - e.g., Sulfasalazine

csDMARDs such as sulfasalazine and methotrexate have shown limited or no efficacy for purely axial symptoms (spinal pain and stiffness) in AS. However, sulfasalazine (typically 2-3 g/day) may be considered for patients with AS who have coexisting peripheral arthritis, as it can be effective for limb joint inflammation. Methotrexate is generally not recommended for axial AS but may be tried for peripheral arthritis if sulfasalazine is ineffective or not tolerated.

Targeted Synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) - JAK inhibitors

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a newer class of oral medications that modulate intracellular signaling pathways involved in inflammation. Several JAK inhibitors (e.g., tofacitinib, upadacitinib, filgotinib) have demonstrated efficacy in treating active AS, particularly in patients who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to NSAIDs or biologic DMARDs. They represent an important oral treatment option.

Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (bDMARDs)

Biologic therapies have significantly advanced the treatment of AS, especially for patients with active disease that is not adequately controlled by NSAIDs. These agents target specific components of the immune system involved in the inflammatory process:

- Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors: This class includes infliximab (IV infusion), adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol (all subcutaneous injections). TNF inhibitors are highly effective in reducing signs and symptoms of AS, improving physical function, and quality of life. They may also slow down radiographic progression of spinal damage in some patients.

- Interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitors: Secukinumab and ixekizumab are monoclonal antibodies that target IL-17A. They are also highly effective for treating active AS, including in patients who have not responded adequately to TNF inhibitors.

Biologic DMARDs are typically considered for patients with persistently high disease activity despite an adequate trial of NSAIDs. Their use requires screening for latent tuberculosis and other infections before initiation, and ongoing monitoring.

Older Immunosuppressants (Historical Context - "Non-hormonal immunosuppressants" or "cytostatics")

Before the availability of biologic therapies, more potent non-hormonal immunosuppressants (sometimes referred to as cytostatics in older literature) like azathioprine (Imuran), cyclophosphamide, or chlorambucil (Leukeran) were occasionally used in very severe, refractory cases of AS, particularly those with significant systemic inflammation or visceral involvement. Dosing regimens were typically 50-100 mg/day for azathioprine or cyclophosphamide, and 5-10 mg/day for chlorambucil, for 2-3 months, with dose reduction upon improvement. These medications carry significant risks of side effects, including myelosuppression (cytopenic syndrome), and require strict hematological monitoring. Their use for AS is now very rare, having been largely superseded by more targeted and effective biologic DMARDs and JAK inhibitors.

Muscle Relaxants for Spasticity

Muscle relaxants may be prescribed as adjunctive therapy to alleviate muscle spasm, which can contribute to pain and stiffness in AS. Examples of commonly available muscle relaxants include cyclobenzaprine, tizanidine, or baclofen. Older or regionally specific drug names like isoprethane and Scutamil-C were mentioned in historical contexts. Therapeutic massage of the back muscles can also be beneficial in reducing muscle spasm and improving comfort.

Non-Pharmacological Therapies

Exercise Therapy (Physiotherapy/Kinesitherapy) and Massage

Therapeutic exercise (physiotherapy or kinesitherapy) is a cornerstone of AS management and should be performed systematically and daily, often 1-2 times a day for at least 30 minutes per session. Regular, lifelong exercise is crucial for maintaining spinal mobility, improving posture, reducing pain and stiffness, strengthening muscles, and enhancing overall function and quality of life. A physiotherapist experienced in AS can develop an individualized exercise program. Exercise therapy in a pool (hydrotherapy) is particularly beneficial as the buoyancy of water reduces stress on joints and facilitates movement, allowing for muscle relaxation and increased range of motion. Specialized apparatus like the "Ugul" (a type of suspension therapy system or "dry pool"), where patients perform exercises while suspended on slings in various positions (lying or sitting), can also be effective by promoting muscle relaxation, relieving pain, and increasing mobility in affected joints.

Massage of the back and paraspinal muscles can help reduce pain, alleviate muscle stiffness and spasm, and improve local circulation and muscle function.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the spine in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis is valuable for detecting early inflammatory changes (sacroiliitis, spondylitis), assessing disease activity, and helping to exclude other organic lesions that might mimic AS.

Physical Modalities (Physiotherapy Treatment)

Various physical therapy modalities may be prescribed as adjunctive treatments, particularly during periods of minimal disease activity or in an inactive phase of AS, to help manage pain and inflammation:

- Ultrasound Therapy: Uses sound waves to generate deep heat and promote tissue healing.

- Phonophoresis with Hydrocortisone: Utilizes ultrasound to enhance the transdermal delivery of topical hydrocortisone for localized anti-inflammatory effects.

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): Delivers low-voltage electrical currents to the skin to help relieve pain.

- Bernard's Currents (Diadynamic Currents): A type of low-frequency electrical stimulation used for pain relief.

- Inductothermy (Shortwave Diathermy): Uses high-frequency electromagnetic currents to generate deep heat in tissues.

- Heat and Cold Therapy: Application of heat (e.g., warm packs) can help relax muscles and reduce stiffness, while cold therapy (e.g., ice packs) can help reduce acute inflammation and pain.

- Reflexotherapy (e.g., Acupuncture): May provide pain relief for some individuals.

- Magnetotherapy: Application of static or pulsed magnetic fields; evidence for efficacy is limited.

- Laser Therapy (Low-Level Laser Therapy - LLLT): Has been used in recent years with some reports of beneficial effects on pain and inflammation.

In the comprehensive treatment of ankylosing spondylitis, the application of physiotherapy to the lumbar spine region can accelerate the reduction of inflammation and pain, and aid in restoring the range of motion in the joints and muscles of the lower back.

Physiotherapy targeted at the cervical spine can be beneficial in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by helping to alleviate inflammation and pain, and improve range of motion in the joints and muscles of the neck.

Spa Treatment (Balneotherapy)

Balneotherapy (treatment with therapeutic baths, often at spa resorts) and mud therapy can provide symptomatic relief and improve well-being for some patients with AS, particularly during periods of low disease activity or in relative remission. Specific types of therapeutic waters and muds are found at various spa locations:

- Radon Baths: Available at resorts like Tskhaltubo (Georgia), Khmelniki (Ukraine).

- Hydrogen Sulfide Baths: Found in locations such as Kemeri (Latvia).

- Mud Therapy (Pelotherapy): Offered at spas like Saki and Evpatoria (Ukraine).

Spa treatment is generally contraindicated during periods of high disease activity or if there is significant involvement or damage to internal organs. It is typically indicated for patients in an inactive or minimally active stage of the disease who are capable of self-care and can tolerate the travel and activities involved.

Patient Monitoring and Follow-up

Long-term, regular monitoring by a rheumatologist is essential for managing AS. The frequency of follow-up visits depends on disease activity, the type of AS (axial vs. peripheral predominant), and the presence of extra-articular manifestations or complications:

- Patients with predominantly peripheral joint involvement may be seen every 1-3 months during active disease, and less frequently when stable.

- Patients with primarily axial disease and stable symptoms might be seen every 4-6 months, or up to 12 months if well-controlled on therapy.

- More frequent monitoring (e.g., monthly or as needed) is required for patients with active uveitis (by an ophthalmologist), significant inflammatory bowel disease (by a gastroenterologist), or other active internal organ involvement.

Monitoring typically includes assessment of disease activity (e.g., using BASDAI, ASDAS scores), physical function (e.g., BASFI), spinal mobility, inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP), and screening for complications. Radiographs of the sacroiliac joints and spine may be performed periodically (e.g., every 1-2 years, or as clinically indicated) to monitor for structural progression, although routine radiographic monitoring frequency is debated, especially with effective biologic therapy. Patients should also have regular ophthalmological check-ups for early detection of uveitis. If an acute exacerbation occurs or outpatient treatment is ineffective, admission for inpatient treatment may be considered to optimize therapy and provide intensive rehabilitation.

Surgical Intervention (Rarely)

Surgery is not a primary treatment for the inflammatory process of AS itself but may be indicated for specific complications or severe deformities that do not respond to conservative management:

- Total Hip Arthroplasty (Hip Replacement): For patients with severe hip joint destruction and pain leading to significant functional impairment. This is one of the more common surgical interventions in AS.

- Total Knee Arthroplasty (Knee Replacement): For severe knee joint damage.

- Spinal Surgery: This is complex and carries significant risks in AS patients due to the rigid, osteoporotic spine. Indications include:

- Correction of severe, disabling spinal deformities (e.g., corrective osteotomy for severe kyphosis to improve gaze and function).

- Stabilization of unstable spinal fractures.

- Decompression of the spinal cord or nerve roots in cases of neurological compromise (e.g., from fracture, atlantoaxial subluxation, or cauda equina syndrome).

Differential Diagnosis of Inflammatory Back Pain

Inflammatory back pain, the cardinal symptom of ankylosing spondylitis, must be differentiated from other conditions that can cause chronic back pain. A careful history, physical examination, appropriate laboratory tests, and imaging are crucial for accurate diagnosis. Other conditions in the spondyloarthritis spectrum share many features with AS.

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | Inflammatory back pain (morning stiffness >30 min, improves with exercise, insidious onset <45 yrs), radiographic sacroiliitis, HLA-B27 often positive, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, uveitis. May have syndesmophytes leading to "bamboo spine." |

| Non-Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) | Similar clinical features to AS (inflammatory back pain, HLA-B27 positivity) but without definitive radiographic sacroiliitis. Active sacroiliitis may be visible on MRI. Can progress to AS. |

| Mechanical Low Back Pain (e.g., Lumbar Strain, Disc Herniation) | Often acute onset, related to specific activity/injury, pain typically worsens with activity and improves with rest. Morning stiffness usually brief (<30 min). May have radicular symptoms (sciatica) with disc herniation. Inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) usually normal. No sacroiliitis. |

| Psoriatic Arthritis (with axial involvement) | Presence of psoriasis (skin rash, nail changes), dactylitis ("sausage digits"), asymmetrical oligoarthritis, enthesitis. Sacroiliitis can occur and may be asymmetrical. HLA-B27 may be positive. |

| Reactive Arthritis | Typically follows a genitourinary (e.g., Chlamydia) or gastrointestinal infection. Classic triad (not always present): arthritis (often lower limb, asymmetrical), urethritis/cervicitis, conjunctivitis/uveitis. Sacroiliitis and enthesitis can occur. HLA-B27 often positive. |

| Enteropathic Arthritis (Arthritis associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease) | Coexisting Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. Axial involvement (sacroiliitis, spondylitis) can be identical to AS. Peripheral arthritis (often large joints, asymmetrical) is common. Flares of arthritis may or may not correlate with bowel disease activity. |

| Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) / Forestier's Disease | Typically affects older individuals (usually >50 years). Characterized by flowing ossification along the anterolateral aspect of at least four contiguous vertebral bodies. Intervertebral disc spaces are preserved. Sacroiliac joints are usually spared, or if involved, changes are different from inflammatory sacroiliitis (e.g., bridging osteophytes across the anterior SI joint). Morning stiffness less prominent than in AS. Inflammatory markers usually normal. |

| Spinal Infection (e.g., Discitis, Vertebral Osteomyelitis, Tuberculous Spondylitis) | Often severe, localized pain, may be associated with fever, chills, and significantly elevated inflammatory markers. Neurological deficits can occur. MRI is key for diagnosis, showing characteristic changes of infection. |

| Spinal Tumors (Primary or Metastatic) (e.g., Vertebral Hemangiomas) | Persistent pain, often worse at night and not relieved by rest ("red flag" symptom). May have neurological deficits or constitutional symptoms (weight loss, fatigue). Imaging (X-ray, CT, MRI, bone scan) is crucial. |

| Degenerative Disc Disease / Spondyloarthrosis (Facet Joint Osteoarthritis) / Spondylosis | More common with increasing age. Pain often related to activity, may have stiffness but typically not prolonged inflammatory morning stiffness. Radiographs show degenerative changes (osteophytes, disc space narrowing, facet joint arthropathy). |

| Osteoporosis with Vertebral Compression Fractures | Can cause acute or chronic back pain, height loss, kyphosis. Often in older individuals or those with risk factors for osteoporosis (including AS itself). Diagnosis by bone density scan and imaging. |

Potential Complications of Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is a systemic disease that can lead to various complications, affecting not only the musculoskeletal system but also other organs:

- Musculoskeletal Complications:

- Spinal Fusion and Deformity: Progressive ankylosis can lead to severe stiffness, significant loss of mobility, and fixed spinal deformities, most commonly thoracic kyphosis ("stooped posture") and loss of lumbar lordosis.

- Osteoporosis and Vertebral Fractures: The inflamed and rigid spine is more prone to osteoporosis and fractures, even with minor trauma. These fractures can be unstable and lead to neurological injury.

- Hip and Shoulder Arthritis: Severe involvement of the hip and shoulder joints can cause significant pain and disability, sometimes requiring joint replacement.

- Peripheral Enthesitis and Arthritis: Can cause chronic pain and functional limitation.

- Atlantoaxial Subluxation: Instability between the first (atlas) and second (axis) cervical vertebrae can occur, potentially leading to spinal cord compression.

- Extra-Articular Complications:

- Acute Anterior Uveitis: Recurrent episodes can lead to complications like cataracts, glaucoma, synechiae, and visual impairment if not treated promptly and effectively by an ophthalmologist.

- Cardiovascular Disease: Increased risk of aortitis (inflammation of the aorta), aortic valve regurgitation, conduction abnormalities (e.g., heart block requiring pacemaker), and possibly accelerated atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease.

- Pulmonary Complications: Restrictive lung disease due to reduced chest wall expansion from costovertebral joint fusion and kyphosis. Apical pulmonary fibrosis (scarring at the lung apices) is a rare but characteristic complication.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Increased association with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Kidney Involvement: Secondary amyloidosis (AA type) is a rare but serious complication in long-standing, poorly controlled disease, leading to kidney failure. IgA nephropathy can also occur.

- Neurological Complications: Aside from fractures and atlantoaxial subluxation, cauda equina syndrome (compression of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal canal) is a rare late complication.

- Impact on Quality of Life: Chronic pain, fatigue, stiffness, reduced physical function, sleep disturbances, and psychological impact (depression, anxiety) can significantly affect the patient's overall quality of life, work ability, and social participation.

Prognosis and Living with Ankylosing Spondylitis

The prognosis of ankylosing spondylitis is highly variable and depends on several factors, including the severity of the disease at onset, the pattern of joint involvement (axial vs. peripheral), the presence of extra-articular manifestations, genetic factors (like HLA-B27 status and other genes), the timeliness of diagnosis, and the response to treatment. With modern therapeutic approaches, particularly the early use of NSAIDs and biologic DMARDs when indicated, along with consistent adherence to exercise programs and lifestyle modifications, many individuals with AS can effectively manage their symptoms, maintain good physical function, prevent or slow down structural damage, and lead active, fulfilling lives. However, some individuals may experience a more aggressive disease course with progressive spinal fusion, significant functional limitations, and complications.

Factors associated with a poorer prognosis may include early hip involvement, severe spinal restriction at diagnosis, persistently high inflammatory markers, poor response to initial NSAID therapy, and smoking. Regular follow-up with a rheumatologist is essential for monitoring disease activity, adjusting treatment as needed, screening for complications, and providing ongoing support and education. Living with AS often requires a long-term commitment to self-management strategies in partnership with the healthcare team.

When to Consult a Rheumatologist

Individuals should be referred to or consult a rheumatologist if they experience symptoms suggestive of ankylosing spondylitis or other forms of inflammatory spondyloarthritis. Key indications for consultation include:

- Chronic Back Pain (lasting >3 months) with Inflammatory Features: Especially if onset is before the age of 45, pain improves with exercise but not with rest, there is significant morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes, or nocturnal pain that awakens the patient.

- Peripheral Arthritis: Unexplained pain and swelling in peripheral joints (hips, shoulders, knees, ankles), particularly if asymmetrical or predominantly affecting the lower limbs.

- Enthesitis: Persistent pain and tenderness at sites where tendons or ligaments attach to bones (e.g., heel pain/plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, pain at costosternal junctions).

- History of Acute Anterior Uveitis: Especially if recurrent or associated with musculoskeletal symptoms.

- Family History of Ankylosing Spondylitis or Related Conditions: Such as psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, or reactive arthritis.

- Unexplained Elevated Inflammatory Markers (ESR, CRP) in the context of musculoskeletal symptoms suggestive of inflammatory arthritis.

- Positive HLA-B27 Test in a patient with suspicious symptoms (though HLA-B27 alone is not diagnostic).

- Suspicion of Sacroiliitis based on clinical symptoms or initial imaging.

Early referral to a rheumatologist is crucial for accurate diagnosis, assessment of disease activity and severity, and timely initiation of appropriate treatment. Early intervention can significantly improve long-term outcomes by controlling inflammation, relieving symptoms, maintaining function, and potentially preventing or slowing down structural damage and disability.

References

- Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun;68 Suppl 2:ii1-44.

- Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X, et al. 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Jun;70(6):896-904.

- Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network Recommendations for the Treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Oct;71(10):1599-1613.

- Zochling J, van der Heijde D, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Apr;65(4):442-52.

- Khan MA. Ankylosing Spondylitis: The Facts. Oxford University Press; 2002.

- Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, et al. The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991 Oct;34(10):1218-27.

- Poddubnyy D, Sieper J. Pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis: recent advances and future directions. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Oct;42(2):121-30.

- Van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jun;76(6):978-991.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome