Spondylitis

- Understanding Spondylitis (Inflammatory Disease of the Spine)

- Specific Types of Infectious Spondylitis

- Non-Infectious Inflammatory Spondyloarthropathies

- Diagnosis of Spondylitis

- Treatment of Spondylitis

- Differential Diagnosis of Back Pain and Spinal Inflammation

- Potential Complications of Spondylitis

- Prevention and When to Seek Specialist Care

- References

Understanding Spondylitis (Inflammatory Disease of the Spine)

Definition and Classification

Spondylitis is a general term referring to an inflammatory disease affecting the vertebrae (bones) of the spine. This inflammation can arise as a consequence of various common infectious diseases or, less commonly, as part of systemic non-infectious inflammatory conditions. Spondylitis can be classified based on its origin (etiology) and clinical course:

- Origin:

- Primary Spondylitis: Inflammation originating directly within the spinal structures.

- Secondary Spondylitis: Inflammation spreading to the spine from an infection elsewhere in the body (hematogenous spread) or from adjacent infected tissues.

- Clinical Course:

- Acute Spondylitis: Rapid onset and progression of symptoms.

- Chronic Spondylitis: Insidious onset and prolonged duration of symptoms.

The clinical picture of spondylitis can vary significantly depending on the specific location of the inflammatory process within the spine (e.g., vertebral body, intervertebral disc, posterior elements) and the extent of bone destruction or associated complications like abscess formation or neurological compression.

General Clinical Features

A hallmark feature of spondylitis of any etiology is a sharp impairment in the mobility of the affected spinal segment. This limitation is often due to reflex tension (spasm) of the paravertebral muscles, which act to splint the inflamed area, effectively blocking movement in all directions (concentric limitation of mobility). This widespread and pronounced reflex-pain limitation of movement is more characteristic of spondylitis than most other spinal diseases.

Common symptoms include:

- Localized back pain, often severe and worse at night or with movement.

- Tenderness to palpation over the affected vertebrae.

- Constitutional symptoms like fever, chills, malaise, weight loss, especially in acute or severe infections.

- Neurological deficits (e.g., weakness, numbness, radicular pain, spinal cord compression symptoms) if the inflammation or its products (abscess, granulation tissue, bony deformity) impinge on neural structures.

- Spinal deformity (e.g., kyphosis, gibbus formation) in chronic or destructive cases like tuberculous spondylitis.

Specific Types of Infectious Spondylitis

Infectious spondylitis (inflammation of the spine due to infection) encompasses a range of conditions caused by different microorganisms, each with distinct characteristics. Historically, **tuberculous spondylitis (Pott's disease)** was the most frequent form, typically presenting as a chronic disease. In contrast, **acute pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine** (caused by bacteria like *Staphylococcus aureus*) is rarer but generally more severe and rapidly progressive. The destructive changes that develop in tuberculous spondylitis over weeks, months, or even years can unfold in acute osteomyelitis of the spine in just a few days. Between these two extremes lie spondylitis caused by other infectious agents such as those responsible for typhoid fever, syphilis, gonorrhea, actinomycosis, and brucellosis.

Tuberculous Spondylitis (Pott's Disease)

This is caused by *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* spreading to the spine, usually hematogenously from a primary focus in the lungs or elsewhere. It typically affects the anterior part of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, leading to caseous necrosis, bone destruction, vertebral collapse, kyphotic deformity (gibbus), and often paraspinal or epidural abscess formation. The course is usually chronic and insidious.

Acute Pyogenic Osteomyelitis of the Spine

Acute osteomyelitis of the spine is a serious and often difficult-to-recognize disease, particularly in its early stages. Patients can deteriorate rapidly, sometimes succumbing to "cryptogenic" sepsis within a few days of onset if diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Young people are affected in at least half of all recognized cases. The lumbar spine is the most common site for acute osteomyelitis, with cervical involvement being rare.

In acute osteomyelitis of the spine, damage to the vertebral bodies, and occasionally the vertebral arches, can occur as a metastatic infection (spread via bloodstream) from a primary focus elsewhere, such as:

- Furunculosis (skin boils)

- Tonsillitis (angina)

- Dental caries or abscesses

- Post-surgical infections (e.g., after removal of the prostate gland or kidney, or operations on the bladder or intestines)

- Urinary tract infections

- Infective endocarditis

Local infection can also be iatrogenically introduced during procedures such as lumbar therapeutic injections (e.g., of the sympathetic borderline trunk), lumbar puncture, spinal anesthesia, or operations on intervertebral discs.

Radiography (X-rays) of the spine in frontal (anteroposterior) and lateral projections is a fundamental imaging modality performed to diagnose spondylitis, revealing characteristic changes in the vertebral bodies such as erosion, collapse, or sclerosis.

Syphilitic Spondylitis

Syphilitic spondylitis, caused by *Treponema pallidum*, usually occurs in the tertiary stage of syphilis. It typically manifests as a gummatous periostitis or osteomyelitis, and rarely as specific diffuse periostitis. Syphilitic spondylitis can be congenital (very rare) or acquired. The cervical vertebrae are predominantly affected in this form of spondylitis. The disintegration of a gumma (a soft, tumor-like growth) within a vertebral body can lead to pathological fractures, vertebral collapse, and subsequent compression of the spinal cord and its nerve roots. The limitation of spinal mobility found on examination in syphilitic spondylitis can be very similar to that seen in tuberculous spondylitis, making differential diagnosis based on clinical signs alone challenging.

Typhoid Spondylitis

Typhoid spondylitis is a rare complication of typhoid fever (enteric fever), caused by *Salmonella Typhi* or *Paratyphi* septicemia. Foci of typhoid infection can sometimes remain dormant ("dumb") in bone and may be reactivated or cause clinical manifestations later, or they may heal without overt clinical signs. Typhoid spondylitis typically affects two adjacent vertebrae and the intervertebral disc located between them. The lumbar spine is most often involved, particularly the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral junctions. Destruction of the intervertebral disc and subsequent synostosis (bony fusion) of the affected vertebrae can occur relatively quickly in typhoid spondylitis, with or without the formation of an abscess. Mobility of the spine is limited in the affected lumbar and thoracic regions. A fixed lordosis (exaggerated inward curve of the lower back) in typhoid spondylitis can be caused by reflex hypertonicity of the back extensor muscles.

Brucellar Spondylitis

Brucellar spondylitis, caused by *Brucella* species, typically occurs in individuals who have occupational contact with infected livestock (e.g., shepherds, farmers, veterinarians, slaughterhouse workers) or consume unpasteurized dairy products from infected animals (e.g., raw milk from infected cows or goats). Symptoms of brucellar spondylitis usually appear 8-12 weeks after the onset of systemic brucellosis (undulant fever). Brucellosis itself is characterized by wave-like (undulant) fever, chills, profound weakness, headache, and arthralgias/myalgias. Brucellar spondylitis affects the vertebral bodies, paravertebral soft tissues, sacroiliac joints, small peripheral joints, and intervertebral discs, often over a large area of the spine. Due to severe pain, which is often difficult to control with rest and medication, the spine can become rigid almost along its entire length.

Imaging in Brucellar Spondylitis: Figure A (Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography - SPECT bone scan) shows increased tracer uptake in affected vertebrae (Th12, L3-L4), indicating active bone turnover. Figure B (Magnetic Resonance Imaging - MRI) shows large and obvious enhancement in the same vertebral bodies (Th12, L3-L4) post-contrast, indicative of inflammation.

Other Infectious Etiologies

Spondylitis can also be caused by other, less common infectious agents, including those responsible for gonorrhea, actinomycosis (a chronic bacterial infection often forming abscesses and sinus tracts), and fungal infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

Non-Infectious Inflammatory Spondyloarthropathies

Ankylosing Spondylitis

It is important to distinguish infectious spondylitis from non-infectious inflammatory diseases of the spine, which are collectively known as spondyloarthropathies. These include conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis (also referred to as progressive chronic spondylitis or rheumatoid spondyloarthritis in older terminology), psoriatic arthritis with axial involvement, reactive arthritis, and enteropathic arthritis. These conditions are autoimmune in nature and are managed differently from infectious spondylitis, primarily with anti-inflammatory drugs, DMARDs, and biologic agents.

Diagnosis of Spondylitis

Diagnosing spondylitis involves a comprehensive approach:

- Clinical History and Physical Examination: Focusing on back pain characteristics, constitutional symptoms, neurological status, risk factors for infection (e.g., IV drug use, recent surgery, immunosuppression, travel to endemic areas for specific infections).

- Laboratory Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): May show leukocytosis.

- Inflammatory Markers: Elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) are common.

- Blood Cultures: To identify bacteremia in pyogenic spondylitis.

- Specific Serological Tests: For suspected tuberculosis (e.g., IGRA), brucellosis, syphilis, typhoid fever.

- Imaging Studies:

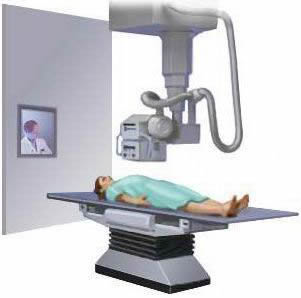

- X-rays: May show disc space narrowing, vertebral endplate erosion, bone destruction, sclerosis, paraspinal soft tissue swelling, or vertebral collapse and deformity in later stages. Early changes may not be visible.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides better detail of bony destruction, sequestra formation, and vertebral alignment. Useful for guiding biopsies.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The most sensitive imaging modality for early detection of spondylitis. It shows inflammation in vertebral bodies (bone marrow edema), intervertebral discs (discitis), paraspinal soft tissues, and epidural space. It is excellent for detecting abscesses and assessing neural compression. Contrast enhancement highlights inflamed tissues and abscess walls.

- Nuclear Medicine Scans (Bone Scan, Gallium Scan, PET-CT): Can detect areas of increased metabolic activity or inflammation, useful in identifying early or multifocal disease. SPECT imaging, as shown in the Brucellosis example, can pinpoint areas of increased tracer uptake.

- Biopsy: CT-guided or open biopsy of the affected vertebral body or disc space is often crucial for definitive diagnosis, especially to obtain tissue for microbiological culture (bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal) and histopathological examination. This helps identify the causative organism and rule out malignancy.

Treatment of Spondylitis

General Principles

The treatment of spondylitis depends fundamentally on its specific type (etiology) and severity. General principles include eradicating the infection (if infectious), relieving pain, preserving or restoring spinal stability and neurological function, and correcting deformities.

Treatment of Pyogenic Osteomyelitis

If pyogenic osteomyelitis of a vertebral body is detected, aggressive treatment is required:

- Antibiotics: Prolonged courses (typically 6-8 weeks or longer) of intravenous antibiotics, followed by oral antibiotics, are the mainstay. The choice of antibiotics is initially empiric (covering common pathogens like *S. aureus*) and then tailored based on culture and sensitivity results from blood or biopsy specimens.

- Surgical Treatment: Often necessary, particularly if there is significant bone destruction, spinal instability, neurological compression (e.g., spinal cord or nerve root compression), epidural abscess, or failure of medical management. The goal of surgery is to debride (remove) infected and necrotic bone and disc material, drain any abscesses, obtain tissue for culture, decompress neural elements, and potentially stabilize the spine with instrumentation and fusion if significant instability is present.

Treatment of Tuberculous Spondylitis

The treatment approach for tuberculous spondylitis is primarily conservative (non-surgical) in uncomplicated cases:

- Anti-tuberculous Chemotherapy: A prolonged course (typically 9-18 months) of multiple specific anti-tuberculosis drugs (e.g., isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol) is the cornerstone of treatment.

- Spinal Immobilization: Bracing or bed rest may be used in the acute phase to relieve pain and prevent deformity.

- Supportive Care: Nutritional support.

- Adjunctive Therapies: Physiotherapy and therapeutic massage are important during the recovery phase to maintain mobility and strength.

- Surgery: Indicated for neurological deficits due to cord compression, significant spinal deformity (kyphosis) causing instability or pain, large paraspinal abscesses requiring drainage, or failure of medical management. Surgical procedures may involve debridement, decompression, and spinal stabilization/fusion.

Management of Other Specific Infectious Spondylitides

Treatment for spondylitis due to syphilis, typhoid, brucellosis, etc., involves specific antimicrobial therapy targeting the causative organism, along with supportive care and management of spinal symptoms similar to other forms of spondylitis.

Surgical Interventions for Complications

In some cases, particularly after resolution of the acute infection, residual bone defects in the vertebrae may require reconstructive procedures. These can include:

- Vertebroplasty or Kyphoplasty: Injection of bone cement into a collapsed or weakened vertebral body to provide stability and relieve pain (more common for osteoporotic fractures or some tumors, less so for primary spondylitis defects unless for stabilization post-infection).

- Spinal Fusion and Instrumentation: Using bone grafts, cages, plates, rods, and screws to stabilize segments of the spine that have become unstable due to bone destruction or deformity.

All reconstructive operations like vertebroplasty and spinal stabilization are performed exclusively after complete sanitation (eradication) of all foci of active vertebral spondylitis infection.

Differential Diagnosis of Back Pain and Spinal Inflammation

Spondylitis must be differentiated from a range of other conditions causing back pain and/or spinal inflammation:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Infectious Spondylitis (Pyogenic, Tuberculous, Brucellar, etc.) | Fever, constitutional symptoms, severe localized back pain, elevated inflammatory markers (ESR/CRP), positive cultures/serology for specific pathogen, characteristic MRI findings (discitis, osteomyelitis, abscess). |

| Ankylosing Spondylitis & other Spondyloarthropathies | Inflammatory back pain (morning stiffness, improves with exercise), sacroiliitis, enthesitis, peripheral arthritis, uveitis. HLA-B27 often positive. No infectious agent identified. Primarily autoimmune. |

| Degenerative Disc Disease / Spondylosis | Chronic pain, often age-related, may have radicular symptoms. X-ray/MRI show osteophytes, disc space narrowing, facet arthropathy. Inflammatory markers usually normal unless acute discitis (rarely non-infectious). |

| Intervertebral Disc Herniation | Often acute onset of radicular pain, numbness, weakness. MRI confirms disc herniation impinging on nerve root. |

| Spinal Tumors (Primary or Metastatic) | Persistent pain, often worse at night, not relieved by rest. May have neurological deficits, constitutional symptoms (weight loss). Imaging (MRI, CT, bone scan) and biopsy are key. |

| Vertebral Compression Fracture (e.g., Osteoporotic) | Acute onset of pain, often after minimal trauma in osteoporotic individuals. X-ray/CT/MRI show vertebral body height loss. |

| Mechanical Back Pain (Strain/Sprain) | Acute onset, often related to activity/injury. Pain localized to muscles/ligaments. Usually improves with rest and conservative measures. No systemic signs of infection. |

Potential Complications of Spondylitis

If not diagnosed and treated effectively, spondylitis can lead to severe complications:

- Spinal Deformity: Kyphosis (e.g., gibbus in Pott's disease), scoliosis.

- Spinal Instability: Due to bone destruction and ligamentous laxity.

- Neurological Deficits: Spinal cord compression or nerve root compression leading to paralysis (paraplegia, quadriplegia), sensory loss, bowel/bladder dysfunction.

- Epidural or Paraspinal Abscess Formation.

- Chronic Pain and Disability.

- Sepsis: Systemic spread of infection, particularly with acute pyogenic spondylitis.

- Sinus Tract Formation: Draining sinuses to the skin or other organs (common in tuberculosis and actinomycosis).

Prevention and When to Seek Specialist Care

Prevention of infectious spondylitis involves:

- Early and effective treatment of systemic infections (e.g., tuberculosis, brucellosis).

- Aseptic techniques during spinal procedures.

- Good hygiene and public health measures to control infectious diseases.

- Vaccination (e.g., BCG for tuberculosis in endemic areas, though its efficacy for preventing spinal TB is variable).

Urgent consultation with a spine specialist (orthopedic or neurosurgeon) and an infectious disease specialist is crucial if spondylitis is suspected, particularly if there are:

- Severe, unremitting back pain, especially if associated with fever or constitutional symptoms.

- New or progressive neurological symptoms (weakness, numbness, bowel/bladder changes).

- Known risk factors for spinal infection (e.g., recent surgery, IV drug use, immunosuppression) and new-onset back pain.

- Signs of spinal deformity.

Prompt diagnosis and multidisciplinary management are essential for optimizing outcomes in patients with spondylitis.

References

- Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010 Nov;65 Suppl 3:iii11-24.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Native Vertebral Osteomyelitis in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Sep 15;61(6):e26-46.

- Turgut M. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease): its clinical presentation, surgical management, and outcome. A survey study on 694 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2001 Apr;24(1):8-13.

- Colmenero JD, Ruiz-Mesa JD, Plata A, et al. Clinical findings, therapeutic approach, and outcome of brucellar spondylitis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008 Jan;60(1):61-7.

- Hadid MS, Sharif S, Ali M, et al. Salmonella Spondylodiscitis: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015 Oct;28(8):E481-7.

- Lifeso RM. Pyogenic Spondylitis. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2017:chap 41.

- Rajasekaran S, Kanna RM, Shetty AP. Management of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Indian J Orthop. 2014 Jan;48(1):31-8. (Context for vertebral body reconstruction, though different etiology).

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome