Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Understanding Lumbago: Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Understanding Lumbodynia (Chronic Low Back Pain): Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Understanding Lumboischialgia (Sciatica): Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Treatment of Lumbago, Lumbodynia, and Lumboischialgia (Sciatica)

- Differential Diagnosis of Low Back Pain and Sciatica

- Complications and Prevention

- When to Consult a Specialist

- References

Understanding Lumbago: Symptoms and Diagnosis

Definition and Mechanisms of Lumbago

Lumbago refers to a sudden onset of paroxysmal, intense pain in the lower back (lumbar region), typically caused by an acute pathological process affecting the structures of the lumbar spine, including intervertebral discs, facet joints, ligaments, or muscles. Lumbago is almost exclusively vertebrogenic (originating from the spine) in nature. While intense lower back pain can also occur during pathological processes in the abdominal cavity (e.g., urolithiasis/kidney stones, appendicitis, peritonitis), these conditions are not classified as lumbago. However, differential diagnosis is crucial, and this is usually achieved through a distinct clinical presentation and findings from a thorough somatic examination by a physician.

The underlying mechanisms of lumbago can involve several factors:

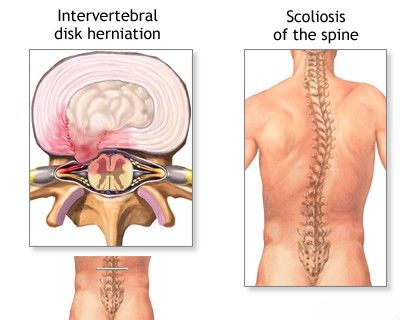

- Acute Discogenic Pain: Rapid movement or displacement of the nucleus pulposus (the inner part of the intervertebral disc), which has been altered by a dystrophic (degenerative) process, towards the annulus fibrosus (the outer ring of the disc). This can cause irritation of pain receptors within the annulus or the sinuvertebral nerve of Luschka, which innervates the posterior aspect of the disc and posterior longitudinal ligament.

- Facet Joint (Zygapophyseal Joint) Dysfunction: Stretching or pinching of the capsular-ligamentous apparatus of the intervertebral (facet) joints, often in the context of underlying spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis).

- Acute Muscular-Tonic Syndrome (Myofascial Pain / Fibromyalgia): An acute attack of severe muscle spasm, often involving the psoas muscle or paraspinal muscles, which can radiate pain to the lower back. This pain can sometimes be described as having a "shingles-like" (herpetiform) quality due to its intensity or distribution, or present as a "lumbago in the legs" if there is referred pain or radicular irritation.

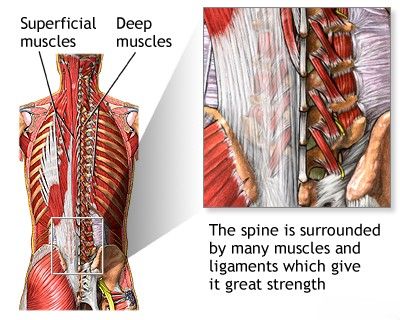

The spine is encased in a network of numerous muscles and ligaments that provide it with substantial strength and mobility. Back pain is often the result of damage to these supportive tissues.

Clinical Manifestations and Examination Findings

Lumbago typically occurs abruptly during or immediately after an awkward movement, bending, lifting a heavy weight, minor injury, or sometimes even spontaneously. Patients often vividly describe the onset of pain as:

- A sudden "push," "rupture," or "crunch" in the lower back.

- A piercing, stabbing pain felt in deep tissues.

- An "electric shock" or "lightning bolt" sensation.

- A compressing ("as if grabbed by ticks"), bursting, boring, or "cerebral" (intense, deep) pain, sometimes with a burning tinge or a feeling of cold, spreading throughout the lower back or localized to its lower parts, often symmetrically.

A patient experiencing an acute lumbago attack often "freezes" in a forced, antalgic (pain-avoiding) posture, as any movement significantly increases the pain. Resting in a horizontal position, particularly with knees flexed, sometimes decreases the pain syndrome. The intense pain of lumbago usually lasts up to 30 minutes initially, but can sometimes persist longer, gradually subsiding into a less severe but still limiting ache.

When attempting to get up from a lying or sitting position, the patient with lumbago carefully "spares" the lower back, often using their arms for support. For example, they might first rest their hands behind their back, then get onto all fours, and slowly rise by "climbing up" their own hips and thighs with their hands (Gowers' sign, though more classically associated with myopathy, can be seen in severe lumbago due to paraspinal muscle inhibition).

Physical examination of a patient with lumbago reveals significant tension and spasm of the paravertebral muscles in the lumbar region. Deep tendon reflexes (knee and Achilles) are usually not changed or may be symmetrically increased due to pain and muscle guarding. True paresis or paralysis is absent, and sensation is typically not impaired in uncomplicated lumbago. However, provocative tests for nerve root tension, such as Lasegue's sign (pain on straight leg raise), Neri's sign (pain on neck flexion), and Dejerine's sign (pain on coughing/sneezing/straining), can be positive due to irritation of pain-sensitive structures or reflex muscle spasm.

After a few hours or days, lumbago pain usually decreases and gradually resolves. However, repeated exacerbations of pain or transformation into other reflex or radicular syndromes associated with lumbar osteochondrosis are possible.

The opinions of various authors regarding the occurrence of lumbago in different age groups are somewhat contradictory. While isolated cases of lumbago are not excluded in adolescence and childhood, it is predominantly a condition of adulthood. In any specific case, particularly in younger individuals, a thorough differential diagnosis is necessary to exclude primary pathological processes of a different nature (e.g., spondylitis, tumor, fracture).

Stenosalgia and Krumpy (Related Calf Pain Syndromes)

By analogy with lumbago, the term "stenosalgia" (from Greek: *stenosis* - narrowing, constriction; *algos* - pain; possibly referring to pain from soleus muscle ischemia or compartment syndrome, though the term is not standard) is described here as an excruciating, compressing, "cerebral," burning pain deep within the triceps surae muscle (calf muscle). Stenosalgia is said to occur paroxysmally and immediately exhibits a very intense character. By the nature of the pain syndrome, it somewhat resembles compressive pain in the region of the heart (angina-like). During the Lasegue test, pain may occur in the buttock and the calf area. This condition must be distinguished from "cramps" (krumpy) – painful tonic contractions of the triceps surae muscles. Isolated cases of muscle cramps are observed in childhood and adolescence, often related to electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, or overuse.

Understanding Lumbodynia (Chronic Low Back Pain): Symptoms and Diagnosis

Etiology and Clinical Features in Children and Adults

Lumbodynia refers to subacute or chronic low back pain that arises as a result of diseases or degenerative processes affecting the structures of the spine. It most commonly occurs in the context of osteochondrosis of the lumbar intervertebral discs. Lumbodynia can affect adults, children, and adolescents with approximately equal frequency in both males and females. However, some studies suggest age-related onset differences: girls may experience it mainly around 11-12 years old (average 11.7 years), while boys might present more commonly at 13-17 years old (average 13.7 years). This could potentially be linked to earlier physical and sexual development in girls, or different patterns of physical activity and growth spurts.

Clinically, lumbodynia is manifested by the presence of moderate or mild persistent pain in the lower back, often accompanied by signs of reflex-tonic muscular protection of the spine (paraspinal muscle spasm and stiffness).

Lumbodynia, or chronic low back pain, often develops as a result of degenerative diseases affecting spinal structures, such as osteoporosis or osteochondrosis.

The onset of pain in lumbodynia is usually preceded or precipitated by various external influences or stresses on the spinal structures:

- Lower back injury (often minor or cumulative).

- Systematic physical fatigue or excessive physical effort.

- Jerky, unguarded movements.

- Prolonged work in an uncomfortable or static position.

- Hypothermia (exposure to cold).

- Acute respiratory diseases or other infections that may trigger inflammatory responses.

- Exacerbation of foci of chronic focal infection elsewhere in the body.

It has also been found that the onset of pain in lumbodynia in children and adolescents often coincides with periods of intense height increase (growth spurts, e.g., up to 8-10 cm per year) and corresponding changes in body weight. These rapid growth phases can contribute to the development of relative spinal instability or biomechanical imbalances. In approximately 20% of patients with lumbodynia, primarily adolescents, transverse whitish stripes (stretch marks or striae distensae) are detected in the lumbosacral region. This can be an indirect confirmation of musculoskeletal inadequacy or rapid tissue stretching during periods of intensive skeletal growth.

When examining children with lumbodynia, tenderness of the paravertebral points and spinous processes is determined in most cases. Significant tension of the lumbar muscles in children with lumbodynia is established in about 25% of cases, which is much less common than in adults with similar complaints. The less frequent occurrence of this muscular-tonic syndrome in pediatric lumbodynia might be explained by the fact that the tension of paravertebral muscles largely depends on the severity of pain and acts as a protective reflex to immobilize the affected part of the spine; children may have different pain perception or muscular responses.

Symptoms of pain provocation or "tension signs" (like Lasegue's sign) with lumbodynia are often moderately or weakly expressed and are determined in approximately one-third of patients. The most common is a mild Lasegue's sign, and in isolated cases, Neri's, Dejerine's, Wasserman's, or Matskevich's signs may be positive. Frank motor disturbances (weakness) and significant changes in tendon-periosteal reflexes are typically absent in pure lumbodynia. Similarly, violations of sensitivity are usually not present.

Radiographic Findings and Associated Anomalies

On radiographs of the spine in children and adolescents with lumbodynia, flattening or smoothness of the lumbar lordosis and the presence of Schmorl's hernias (intraspongy disc herniations into the vertebral body endplates) were often found (in approximately 50% of cases in some series). Schmorl's hernias are usually multiple, can be large in size, and are often located in the anterior areas of the endplates of the upper lumbar vertebrae. They can sometimes cause deformation and a decrease in the height of one or two vertebrae. In the lower lumbar vertebrae, discs usually prolapse (herniate) into the posterior halves of the vertebral body endplates. Small, single Schmorl's hernias are probably of no direct clinical significance in causing lumbodynia. However, in some cases, they differ significantly from the classic mushroom-shaped Schmorl's cartilaginous nodules and may reflect a more widespread degenerative lesion of the intervertebral discs.

Pain syndrome (lumbodynia) in the presence of multiple or large Schmorl's hernias is, in most cases, persistent and can be difficult to manage with conservative therapy. Somewhat less often with lumbodynia, small antalgic scoliosis of the lumbar spine is determined, frequently combined with the smoothness of lumbar lordosis. A decrease in the height of the intervertebral spaces was an extremely rare isolated finding in some historical pediatric series of lumbodynia.

In addition to these degenerative changes, patients with lumbodynia may also have underlying congenital anomalies of the lumbosacral spine revealed on imaging:

- Splitting of the vertebral arch (spina bifida occulta).

- Transitional lumbosacral vertebra (lumbarization of S1 or sacralization of L5).

Course and Prognosis of Lumbodynia

The course of lumbodynia can be long and chronic, characterized by periods of remission alternating with recurrences of back pain. Even after the acute pain syndrome subsides, a feeling of discomfort or stiffness in the lower back may persist for a long time. This indicates that the patient's treatment and rehabilitation may not have been fully completed or that underlying predisposing factors remain unaddressed, leading to a risk of future exacerbations.

Understanding Lumboischialgia (Sciatica): Symptoms and Diagnosis

Definition and Contributing Factors

Lumboischialgia, commonly known as sciatica, is defined as acute, subacute, or chronic low back pain that radiates into one or both legs, typically along the distribution of the sciatic nerve or its contributing nerve roots (L4, L5, S1, S2, S3). Similar to lumbodynia, lumboischialgia encompasses pain symptoms and syndromes of corresponding localization caused by pathology of the spine, predominantly osteochondrosis of the lumbar intervertebral discs leading to nerve root irritation or compression (radiculopathy). The onset of lumboischialgia is usually facilitated by the influence of the same factors that contribute to lumbodynia, such as trauma, physical strain, degenerative changes, and inflammatory processes.

Lumboischialgia (sciatica) is defined as subacute or chronic low back pain that radiates down into one or both legs, often due to irritation or compression of the sciatic nerve or its roots.

Clinical Differences from Lumbodynia

In terms of clinical manifestations and symptoms, lumboischialgia shares some common features with lumbodynia:

- Both conditions can present with moderate or mild pain syndrome in the lower back as a primary component.

- Lumboischialgia and lumbodynia have a similar frequency of occurrence across different age groups and sexes in children and adults, although specific onset patterns may vary.

- Both are generally considered as reflex or compressive syndromes affecting the peripheral nervous system as a result of underlying spinal diseases.

However, there are several quantitative and qualitative differences between lumboischialgia and pure lumbodynia:

- Nerve Root Tension Signs: In lumboischialgia, symptoms of nerve root tension (e.g., Lasegue's sign, Bragard's sign) are determined in almost all cases and are often more pronounced than in lumbodynia.

- Muscle Tension: Tension of the lumbar (paravertebral) muscles is detected much less frequently in children with lumboischialgia compared to adults with this pathology or children with pure lumbodynia.

- Sensory Deficits: Unlike lumbodynia, patients with lumboischialgia sometimes exhibit mild hypalgesia (reduced pain sensation) or other sensory changes (paresthesia like numbness, tingling) in the feet or along a specific dermatomal distribution in the leg corresponding to the affected nerve root.

- Motor and Reflex Changes: On the side of pain localization, there may be slight muscle weakness (hypotonia) and/or hypotrophy (muscle wasting) of the thigh or lower leg muscles. Additionally, with lumboischialgia, knee (L4 root) and Achilles (S1 root) reflexes may be diminished or absent on the affected side.

- Autonomic Disturbances: Vegetative disorders such as hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating) or a sensation of chilliness in the affected leg(s) can be noted.

Clinical Variants and Radiographic Correlates

Several clinical variants of lumboischialgia are recognized, depending on the predominant pathophysiological mechanism:

- Lumboischialgia with leading

muscular-tonic manifestations

(significant muscle spasm and trigger points). - Lumboischialgia with

vegetative-vascular manifestations

(changes in skin temperature, color, sweating). - Lumboischialgia with

neurodystrophic manifestations

(trophic changes in skin, nails, or subcutaneous tissue due to chronic nerve irritation – rare in children).

In childhood, lumboischialgia predominantly features muscular-tonic disorders. Vegetative-vascular disorders are much less common, and the neurodystrophic form of lumbar ischialgia has historically not been frequently detected in children and adolescents, although this does not exclude the possibility of its existence at this age in severe or chronic cases.

On radiographs of the spine, scoliosis of the lumbar spine is found with the same frequency in lumboischialgia as in lumbodynia, often combined with smoothness (loss) of the normal lumbar lordosis. However, Schmorl's hernias are found much less often with lumboischialgia compared to lumbodynia. Instead, other indirect signs of lumbar osteochondrosis are more frequently observed, such as a decrease in the height of intervertebral spaces, "fish vertebrae" (biconcave vertebral bodies), or lateral displacement of a vertebral body (laterolisthesis).

Congenital malformations of the lumbosacral spine (e.g., spina bifida occulta, transitional vertebrae) are much more common in patients with lumboischialgia (found in up to 50% in some series) than in other clinical manifestations of lumbar osteochondrosis. These anomalies, by themselves, do not directly lead to lumbosacral pain. However, they can contribute to a decrease in the static stability of the spine and may accelerate the development of degenerative changes in the intervertebral discs adjacent to the anomaly, especially with increased physical exertion. It can be assumed that lumboischialgia in children, in contrast to lumbodynia, may occur with less significant external influences but against the background of more pronounced congenital structural changes in the spine. This ultimately contributes to the subsequent development of true radicular syndromes of lumbar osteochondrosis due to nerve root compression.

Treatment of Lumbago (Low Back Pain) and Sciatica

The management of acute lumbago, chronic lumbodynia, and lumboischialgia (sciatica) involves a multifaceted approach aimed at relieving pain, reducing inflammation, restoring function, and preventing recurrence. The specific treatment plan depends on the underlying cause, severity, and duration of symptoms.

Lumbago is characterized by a sudden onset of paroxysmal, intense low back pain, often triggered by pathological processes within the structures of the lumbar spine and intervertebral discs, leading to significant functional limitation.

Initial Management and Lifestyle Adjustments

For acute episodes of lumbago or severe sciatica, initial management often includes:

- Relative Rest: A patient with lumbago or acute sciatica should generally remain in bed for 3-5 days during the most acute phase. If possible, lying on a firm, hard surface is recommended.

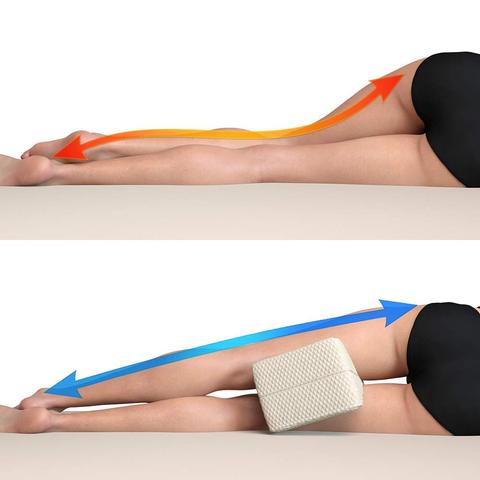

- In the supine position (lying on the back), placing a rolled blanket or pillow under the knees can help relieve tension in the muscles of the lower back.

- In the lateral (side-lying) position, a pillow or cushion placed between the knees can provide pain relief and help maintain spinal alignment.

- Activity Modification: Avoid activities that aggravate pain, such as heavy lifting, prolonged sitting or standing, and bending or twisting movements.

- Lumbar Brace/Support: When moving or in a sitting position, a patient may benefit from using a lumbar brace or corset to provide support and limit painful motion.

Wearing a lumbosacral corset can help relieve pain associated with lumbago, lumbodynia, and lumboischialgia, particularly when these conditions arise from spinal osteochondrosis with herniated intervertebral disc or disc protrusion.

When sleeping on your side, using a pillow between the knees that is just thick enough to keep the upper knee elevated helps maintain a level spine and can reduce strain on the lower back and hips.

Benefits of sleeping with a pillow between the legs when side-lying include:

- Reduced or prevented low back pain by maintaining neutral spinal alignment.

- Alleviation of sciatica pain by reducing tension on the sciatic nerve.

- Reduced knee pain by preventing the upper knee from dropping and stressing the hip/knee.

- Reduced hip pain by aligning the hip joint.

A pillow that is relatively flat and appropriately sized (not too big or too small) often works well. The goal is to elevate the upper knee just enough so that the spine remains relatively straight and level.

Pharmacological Therapy

Medications for lumbago, lumbodynia, and lumbar ischialgia include:

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen or stronger pain relievers.

- Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Such as ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac (Voltaren), or Xefo (lornoxicam - this name, Xefedamicam, seems like a typo for Lornoxicam or similar). These help reduce pain and inflammation. Analgin (metamizole) and Rheopyrin (a combination of phenylbutazone and aminophenazone) are older drugs with significant potential side effects and are less commonly used in many regions now.

- Muscle Relaxants: To alleviate painful muscle spasms.

- Neuropathic Pain Medications: For sciatica or radicular pain, drugs like gabapentin, pregabalin, or tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) may be effective.

- Dehydrating Drugs (Diuretics - Historical/Uncommon for this purpose now): Historically, drugs like furosemide, Diacarb (acetazolamide), or Lasix (furosemide) were sometimes prescribed, possibly with the intent to reduce edema around nerve roots, but this is not standard practice for lumbago/sciatica today.

- Antidepressants (e.g., Nialamide - a MAOI, historical): Some antidepressants, particularly tricyclics or SNRIs, are used for chronic pain and neuropathic pain. MAOIs like nialamide are rarely used now due to dietary restrictions and drug interactions.

- Carbamazepine Analogs (e.g., Finlepsin/carbamazepine): Can be effective for neuropathic pain in some cases of lumbago or radiculopathy.

Interventional Pain Management (Therapeutic Injections)

Therapeutic injections (blockades) into or around the intervertebral (facet) joints of the lumbar spine, epidural space, or trigger points can be performed if conventional treatment does not provide sufficient relief. These injections, often containing a local anesthetic (e.g., novocaine/procaine, lidocaine) and a corticosteroid (e.g., cortisone, Diprospan/betamethasone, Kenalog/triamcinolone), aim to rapidly reduce pain and inflammation at the source. Low doses are typically sufficient. When combined with a properly selected physiotherapy regimen, these blockades can have a good and long-term positive effect for the patient.

Manual Therapy, Physiotherapy, and Acupuncture

- Manual Therapy: Techniques such as spinal mobilization/manipulation, soft tissue mobilization, and specific muscle energy or radicular techniques may be employed to restore joint mobility, reduce muscle spasm, and alleviate nerve irritation. Some practitioners may attempt non-surgical "reduction" of a vertebral disc herniation using these methods.

- Physiotherapy (Physical Therapy): Essential for recovery and prevention. Includes:

- Exercises to strengthen core muscles, improve flexibility, and promote proper posture.

- Modalities like heat, cold, TENS, ultrasound, or UHF therapy.

- Education on body mechanics and self-management.

- Acupuncture (Reflexotherapy): Can be effective in treating lumbago, lumbodynia, and lumbar ischialgia by modulating pain pathways and promoting muscle relaxation.

Physiotherapy plays a key role in the treatment of lumbago, lumbodynia, and lumbar ischialgia by helping to eliminate inflammation and pain, and by restoring movement in the joints and muscles of the lower back.

Acupuncture is often an effective complementary therapy in treating lumbago, lumbodynia, and lumbar ischialgia, helping to alleviate pain and muscle tension.

Surgical Treatment (When Indicated)

Surgical intervention is considered if conservative treatments fail after an adequate period (typically 6-12 weeks), or if there are "red flag" signs such as progressive neurological deficits or cauda equina syndrome (a surgical emergency). Surgical options depend on the underlying pathology and may include microdiscectomy, laminectomy, or spinal fusion.

In the future, the patient who has experienced lumbago, lumbodynia, or lumbar ischialgia should, whenever possible, choose professions or modify work activities to avoid increased physical exertion on the spine, exposure to significant temperature drops, prolonged vibration, and long-term work in forced, monotonous positions.

Differential Diagnosis of Low Back Pain and Sciatica

It's important to differentiate these common spinal syndromes from other potential causes of low back and leg pain:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Lumbago (Acute Low Back Pain) | Sudden onset, severe localized low back pain, often after movement/lifting. Marked muscle spasm, limited mobility. No significant leg radiation typically. |

| Lumbodynia (Chronic Low Back Pain) | Persistent or recurrent low back pain (>3 months), often aching. May have stiffness. Usually no significant radicular symptoms. |

| Lumboischialgia (Sciatica) | Low back pain radiating down the leg along sciatic nerve distribution (buttock, posterior/lateral thigh, calf, foot). May have numbness, tingling, weakness. Positive nerve tension signs (SLR). |

| Lumbar Spinal Stenosis | Neurogenic claudication (leg pain/numbness with walking/standing, relieved by sitting/flexion). Often bilateral. Older age group typical. |

| Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction/Sacroiliitis | Pain over SI joint, buttock, groin, may refer to posterior thigh (pseudo-sciatica). Positive SI joint provocative tests. |

| Piriformis Syndrome | Buttock pain, may mimic sciatica due to sciatic nerve irritation by piriformis muscle. Tenderness over piriformis. |

| Hip Pathology (e.g., Osteoarthritis) | Groin pain, pain with hip movement. Can refer to buttock or thigh. |

| Vascular Claudication | Leg pain/cramping with exercise, relieved by rest (not necessarily position change). Diminished peripheral pulses, skin changes. |

| "Red Flag" Conditions (e.g., Tumor, Infection, Fracture) | Persistent night pain, unexplained weight loss, fever, history of cancer/trauma, immunosuppression, rapidly progressive neurological deficits. Require urgent investigation. |

Complications and Prevention

Potential complications of untreated or severe lumbago and sciatica include:

- Chronic pain and disability.

- Progressive neurological deficits (weakness, sensory loss).

- Cauda equina syndrome (rare but serious).

- Reduced quality of life and functional impairment.

- Psychological distress (anxiety, depression).

Prevention involves:

- Maintaining good posture and body mechanics.

- Regular exercise to strengthen core and back muscles.

- Avoiding prolonged static positions and taking regular breaks.

- Using proper lifting techniques.

- Maintaining a healthy weight.

When to Consult a Specialist

While mild low back pain often resolves with self-care, consultation with a neurologist, neurosurgeon, orthopedic spine specialist, or pain management physician is recommended if:

- Pain is severe, persistent (beyond a few weeks), or disabling.

- There is radiating leg pain (sciatica), especially if associated with numbness, tingling, or weakness.

- "Red flag" symptoms are present (see Differential Diagnosis table).

- Symptoms significantly impact daily life or sleep.

- Conservative measures fail to provide relief.

A specialist can provide an accurate diagnosis and develop an appropriate, individualized treatment plan.

References

- Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001 Feb 1;344(5):363-70.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Oct 2;147(7):478-91.

- Valat JP, Genevay S, Marty M, Rozenberg S, Koes B. Sciatica. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010 Apr;24(2):241-52.

- Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 2009 Dec 15;147(1-3):17-9.

- Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 2007 Jun 23;334(7607):1313-7.

- Wheeler AH. Diagnosis and management of low back pain and sciatica. Am Fam Physician. 1995 Oct;52(5):1333-41, 1345-6.

- Stafford MA, Peng P, Hill DA. Sciatica: a review of history, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and the role of epidural steroid injection in management. Br J Anaesth. 2007 Oct;99(4):461-73.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Vol. 2. The Lower Extremities. Williams & Wilkins; 1992.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome