Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Understanding Pain in Thoracic Spine Osteochondrosis

- Understanding Intercostal Neuralgia

- Diagnosis of Thoracic Spine Pain and Intercostal Neuralgia

- Treatment of Thoracic Spine Pain and Intercostal Neuralgia

- Duration of Treatment and Prognosis

- Differential Diagnosis of Thoracic Pain

- Prevention and When to Consult a Specialist

- References

Understanding Pain in Thoracic Spine Osteochondrosis

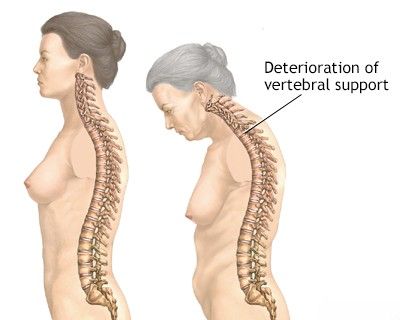

Pain in the thoracic spine is a common complaint that can affect individuals in adulthood, often closely linked to their lifestyle and daily activities. While "osteochondrosis of the thoracic spine" is a term frequently used, particularly in some regions, to describe degenerative changes in the intervertebral discs and adjacent vertebral bodies, it's important to understand that thoracic pain can have multiple origins, with muscular issues being very prevalent.

Etiology and Contributing Factors

Symptoms of back pain, including in the thoracic region, frequently trouble individuals in adulthood and are often associated with their lifestyle habits. Patients experiencing pain attributed to degenerative changes of the thoracic spine (often termed osteochondrosis) typically engage in activities or have habits that promote a sedentary lifestyle. This includes prolonged periods working at a computer, long-duration driving, extended studying, or postures adopted during activities like breastfeeding. Hypothermia (exposure to cold) can also be a trigger. Less commonly, pain symptoms might appear in individuals with physically demanding or highly mobile work, or paradoxically, in those leading an active lifestyle if improper technique or overuse leads to strain.

Common Symptoms and Pain Sources

Patients with symptoms of pain often attributed to osteochondrosis of the thoracic spine typically present with the following complaints:

- Pulling or aching pain located between the shoulder blades (interscapular pain).

- A burning sensation between the shoulder blades.

- Pain in the region of the heart (pseudoanginal pain) or under the chest (inframammary pain), which may occur with movement or even at rest, sometimes mimicking cardiac conditions.

- Girdle-like pain radiating between the ribs, often towards the axillary (armpit) line.

- Pain in the thoracic region that intensifies after prolonged sitting (e.g., at the end of a workday) or upon waking after sleep.

Pain in the thoracic spine is primarily **myofascial (muscular) in origin** in many cases. During clinical examination, specialists often identify tender trigger points in characteristic locations within the muscles of the thoracic spine and the broader chest area. The intercostal muscles (muscles between the ribs) and the erector spinae muscles (extensor muscles of the spine) are most frequently implicated as sources of pain in the context of thoracic osteochondrosis or general thoracic dysfunction. Less commonly, pain can be localized in the adductor muscles of the shoulder (e.g., rhomboids, trapezius) or the pectoral muscles, referring pain to the thoracic region.

Beyond muscular sources, pain in the thoracic spine can also originate from tendons, ligaments, joint capsules of the facet joints (zygapophyseal joints) or costovertebral joints, the vertebral bodies themselves, or their processes. Specific examples include:

- Pain in the thoracic spine originating from the intervertebral (facet) joints due to arthropathy or inflammation.

- Pain at the costovertebral joints (points of attachment of the rib heads to the vertebral bodies).

- Pain at the costosternal or costochondral junctions (points of attachment of the ribs to the sternum via cartilage).

These non-muscular sources of pain in the thoracic spine are most often associated with direct trauma to these spinal or chest structures (e.g., from falls, sudden heavy lifting, or awkward, forceful movements).

Understanding Intercostal Neuralgia

Intercostal neuralgia is characterized by neuropathic pain in the distribution of one or more intercostal nerves, which run along the intercostal spaces (between the ribs). The pain is often described as sharp, burning, aching, or stabbing, typically felt in a band-like pattern around the chest or upper abdomen, following the course of the affected rib(s).

Viral Intercostal Neuralgia (Herpes Zoster / Shingles)

A common viral cause of intercostal neuralgia is **Herpes Zoster**, also known as shingles. This condition results from the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (the same virus that causes chickenpox), which lies dormant in the dorsal root ganglia of spinal nerves. When reactivated, the virus travels along the sensory nerve (in this case, an intercostal nerve) to the skin, causing inflammation and damage to the nerve itself (neuralgia) and a characteristic vesicular rash.

Symptoms include:

- Prodromal Phase: Before the rash appears, patients often experience itching, tingling, burning, or pain along the affected dermatome (skin area supplied by the nerve) for several days. This is the incubation period where the virus is actively dividing within the myelin sheath of the intercostal nerve.

- Pain: The pain of herpetic intercostal neuralgia can be severe, often described as piercing, "dagger-like," or intensely burning, even with light contact with seemingly healthy skin in the intercostal space.

- Rash: After the prodromal pain, a characteristic rash of painful blisters (vesicles) filled with clear fluid appears on an erythematous base, strictly following the distribution of the affected intercostal nerve(s), usually unilaterally. These blisters are extremely painful upon contact with clothing or bedding. The blisters eventually crust over and heal.

- Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN): In some individuals, particularly older adults, the pain can persist for months or even years after the rash has healed, a condition known as postherpetic neuralgia.

Patients often confuse the muscular pain associated with thoracic osteochondrosis with the distinct neuropathic pain of intercostal neuralgia.

Traumatic Intercostal Neuralgia

Traumatic injuries to the chest wall, such as rib fractures, direct contusions, or surgical incisions (e.g., thoracotomy), can lead to compression, stretching, or direct damage to the intercostal nerves or their sheaths. This manifests as acute local or girdle-like pain along the affected intercostal space. The pain can be sharp, aching, or burning and may be exacerbated by movement, deep breathing, coughing, or palpation of the area. The pain can radiate along the course of the intercostal nerve, potentially involving the anterior chest wall or upper abdomen on the side of the injury.

Diagnosis of Thoracic Spine Pain and Intercostal Neuralgia

The diagnosis of pain originating from thoracic spine osteochondrosis (degenerative changes) and intercostal neuralgia is generally straightforward for experienced clinicians but requires a careful history and physical examination. Differentiating between myofascial pain, facet joint pain, discogenic pain, and true intercostal neuralgia is key.

- Clinical Examination:

- Palpation: Identifies sources of pain, such as trigger points in paraspinal or intercostal muscles, tenderness over facet joints, costovertebral joints, or along the course of an intercostal nerve.

- Functional Tests: Assessing range of motion of the thoracic spine and chest wall, and observing pain provocation with specific movements.

- Skin Examination: Crucial for identifying the characteristic vesicular rash of herpes zoster in cases of viral intercostal neuralgia.

- Neurological Examination: To assess for any sensory deficits in a dermatomal pattern (suggesting nerve root or intercostal nerve involvement) or motor weakness.

- Diagnostic Injections: In some cases, local anesthetic blocks of trigger points, facet joints, or intercostal nerves can have diagnostic value if they provide significant pain relief.

- Additional Diagnostic Procedures: If there is doubt about the diagnosis of thoracic spine osteochondrosis or intercostal neuralgia, or if "red flag" symptoms (e.g., unexplained weight loss, fever, neurological deficits, history of cancer) are present, further investigations may be prescribed:

- X-ray of the Thoracic Spine: Can show degenerative changes, fractures, or gross spinal deformities.

- CT Scan of the Thoracic Spine: Provides more detailed bony anatomy, useful for evaluating fractures, severe degenerative changes, or bony tumors. Multispiral CT (MSCT) offers high resolution.

- MRI of the Thoracic Spine: Excellent for visualizing soft tissues, including intervertebral discs (herniations, degeneration), spinal cord, nerve roots, ligaments, and detecting inflammation or tumors.

- Blood Tests for Viral Infection: If herpes zoster is suspected but the rash is atypical or absent (zoster sine herpete), viral cultures, PCR, or serological tests might be considered, though diagnosis is often clinical. Blood tests can also check for inflammatory markers.

CT and MRI of the thoracic spine is a valuable imaging technique for diagnosing various causes of pain in this region, including degenerative changes, yellow ligament ossification, fractures, or other pathologies contributing to thoracic pain or intercostal neuralgia.

Treatment of Thoracic Spine Pain and Intercostal Neuralgia

The therapeutic approach depends on the underlying cause, severity of manifestations, and specific diagnosis (e.g., myofascial pain from thoracic osteochondrosis vs. viral intercostal neuralgia).

Pharmacological Therapy

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): For musculoskeletal pain and inflammation (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac).

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen or stronger pain relievers if NSAIDs are insufficient or contraindicated.

- Muscle Relaxants: For associated muscle spasm.

- Antiviral Drugs: For acute herpes zoster (shingles), antiviral medications (e.g., acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) started early (ideally within 72 hours of rash onset) can reduce the severity and duration of the acute illness and may decrease the risk of postherpetic neuralgia.

- Neuropathic Pain Medications: For intercostal neuralgia (especially postherpetic neuralgia or chronic traumatic neuralgia), medications like gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline), or SNRIs (e.g., duloxetine) are often used.

- Topical Treatments: Lidocaine patches or capsaicin cream can provide relief for localized neuropathic pain like PHN.

- Vitamin B Complex: Sometimes prescribed as adjunctive therapy for nerve health, though evidence for significant benefit in neuralgia is limited.

- Hormones (Corticosteroids): Systemic corticosteroids may be considered for severe acute inflammation or pain in some cases of herpes zoster (to reduce acute pain and potentially risk of PHN, though controversial) or for severe inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions, but generally not for routine thoracic osteochondrosis pain. Epidural or facet joint steroid injections are more targeted.

Therapeutic Injections (Blockades)

Therapeutic injections can be very effective for specific types of thoracic pain:

- Trigger Point Injections: Injection of local anesthetic (e.g., novocaine/procaine, lidocaine) with or without a corticosteroid (e.g., cortisone, diprospan/betamethasone, kenalog/triamcinolone) directly into painful muscle trigger points (myofascial seals) in the intercostal or paravertebral muscles.

- Intercostal Nerve Blocks: Injection of local anesthetic and/or steroid around the affected intercostal nerve can provide significant relief for intercostal neuralgia.

- Facet Joint (Zygapophyseal Joint) Injections: If pain is suspected to originate from the facet joints in thoracic osteochondrosis or spondyloarthrosis, injections into or around these joints can be performed. These are generally used when conventional treatment for thoracic spine pain and intercostal neuralgia is not consistently beneficial. Low doses of anesthetic and corticosteroid injected into the lumen or near the affected joint are often sufficient.

Therapeutic injections, such as trigger point injections or nerve blocks, are utilized to alleviate pain associated with thoracic spine conditions and intercostal neuralgia by delivering anesthetic and/or anti-inflammatory medication directly to the source of pain.

Manual Therapy

Techniques such as soft tissue mobilization, myofascial release, joint mobilization, or osteopathic manipulative techniques may be beneficial for musculoskeletal pain, muscle spasm, and restricted joint mobility associated with thoracic spine dysfunction.

Manual therapy techniques, including soft tissue work and joint mobilization, are often applied to the thoracic spine to address pain, muscle tension, and restricted movement.

Physiotherapy (Physical Therapy)

Modalities like heat, cold, ultrasound, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), or UHF therapy may be used to reduce pain and inflammation.

Exercise Therapy (Therapeutic Gymnastics)

Specific exercises to improve posture, strengthen core and paraspinal muscles, and increase flexibility of the thoracic spine and chest wall are important for long-term management.

Acupuncture (Reflexotherapy)

Acupuncture can be very effective in the treatment of pain associated with thoracic spine osteochondrosis and some forms of intercostal neuralgia by modulating pain pathways and promoting muscle relaxation.

The application of acupuncture (reflexotherapy) is often highly effective in managing pain stemming from osteochondrosis of the thoracic spine and intercostal neuralgia.

Surgical Treatment (Rare)

Surgery is rarely indicated for thoracic spine pain due to osteochondrosis or uncomplicated intercostal neuralgia. It may be considered in specific situations such as severe, refractory pain from a large thoracic disc herniation causing myelopathy or intractable radiculopathy, spinal instability, or tumors compressing nerves.

Duration of Treatment and Prognosis

For pain in the muscles, ligaments, or joint capsules related to thoracic spine osteochondrosis, the duration of outpatient treatment can be around 1.5-2 weeks from the onset of acute pain, with a good prognosis for recovery with appropriate conservative management.

In cases of viral intercostal neuralgia (herpes zoster), especially in elderly or debilitated patients, outpatient treatment of the neuralgia (particularly postherpetic neuralgia) can be prolonged, potentially lasting from 0.5 to 1.5 months, or even longer for PHN. Early antiviral treatment for shingles can shorten the acute illness and may reduce the risk and severity of PHN.

Differential Diagnosis of Thoracic Pain

Thoracic pain can have many origins, and it's crucial to rule out serious conditions, especially those involving visceral organs, before attributing pain solely to musculoskeletal or neuralgic causes related to the thoracic spine.

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Thoracic Spine Osteochondrosis / Myofascial Pain | Pain often related to posture, activity; trigger points in paraspinal/interscapular muscles; may have localized tenderness over facet joints or costovertebral joints. Relieved by rest, heat, manual therapy. |

| Intercostal Neuralgia | Sharp, burning, or aching pain in a band-like distribution along an intercostal space. If herpes zoster, characteristic vesicular rash in dermatomal pattern. Tenderness along intercostal nerve. |

| Thoracic Disc Herniation | Less common than cervical/lumbar. Can cause axial pain, radicular pain (band-like), or myelopathy if large and central. MRI is diagnostic. |

| Rib Fracture / Contusion | History of trauma. Localized tenderness over rib, pain with deep inspiration or coughing. X-ray or CT can confirm fracture. |

| Costochondritis / Tietze's Syndrome | Inflammation of costochondral or costosternal junctions. Localized chest wall pain and tenderness, often sharp. Tietze's involves swelling. |

| Cardiac Pain (e.g., Angina, Myocardial Infarction) | Retrosternal or precordial pressure, tightness, or pain, may radiate to arm/jaw/neck. Associated with exertion (angina) or rest (MI). Shortness of breath, sweating, nausea. ECG, cardiac enzymes crucial. **This is an emergency.** |

| Pulmonary Conditions (e.g., Pleurisy, Pneumonia, Pulmonary Embolism) | Pleuritic chest pain (sharp, worse with breathing/coughing), cough, fever, shortness of breath. Chest X-ray, CT scan. **Pulmonary embolism is an emergency.** |

| Esophageal or Gastric Pain (e.g., GERD, Esophagitis, Peptic Ulcer) | Burning retrosternal pain (heartburn), often related to meals, lying down. May radiate to back. Dysphagia, regurgitation. |

| Gallbladder Disease (e.g., Cholecystitis) | Right upper quadrant abdominal pain, may radiate to right shoulder/scapula. Often postprandial, especially after fatty meals. Nausea, vomiting. |

| Spinal Infections (e.g., Discitis, Vertebral Osteomyelitis) or Tumors | Persistent, often severe pain, may be worse at night. Fever, weight loss, neurological symptoms possible. Requires imaging (MRI/CT) and often biopsy. |

Prevention and When to Consult a Specialist

Preventive measures for musculoskeletal thoracic pain include:

- Maintaining good posture during sitting, standing, and lifting.

- Regular exercise to strengthen core and back muscles.

- Ergonomic adjustments at the workplace.

- Avoiding prolonged static postures; taking regular breaks.

- Managing stress, which can contribute to muscle tension.

- Vaccination against shingles (for eligible adults) to prevent herpes zoster.

Consultation with a physician (e.g., general practitioner, neurologist, pain management specialist, or rheumatologist) is advisable if:

- Thoracic pain is severe, persistent, or progressively worsening.

- Pain is associated with "red flag" symptoms such as fever, unexplained weight loss, night sweats, neurological deficits (weakness, numbness, bowel/bladder dysfunction), or history of cancer.

- There is a suspicion of herpes zoster (shingles).

- Pain significantly impacts daily activities or sleep.

- Pain does not improve with self-care measures or simple analgesics.

- There are concerns about cardiac or other visceral causes of pain.

Accurate diagnosis is key to effective treatment and ruling out more serious underlying conditions.

References

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Vol. 1. Upper Half of Body. 2nd ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

- Cohen SP, Argoff CE. Management of low back pain. BMJ. 2008 Aug 28;337:a2718. (General principles applicable to spinal pain)

- Johnson RW, Rice ASC. Clinical practice. Postherpetic neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 2014 Oct 16;371(16):1526-33.

- Manchikanti L, Singh V. Interventional techniques in the management of chronic pain. Pain Physician. 2001 Jan;4(1):37-70. (Includes intercostal nerve blocks)

- Allegri M, Montella S, Salici F, et al. Mechanisms of low back pain: a guide for diagnosis and therapy. F1000Res. 2016;5:F1000 Faculty Rev-1530.

- Van Eerd M, Patijn J, Lataster A, et al. 5. Intercostal neuralgia. Pain Pract. 2010 Jan-Feb;10(1):66-72.

- Stochkendahl MJ, Christensen HW. Chest pain in musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010 May;33(4):308-16.

- Harden RN, Oaklander AL, Cruccu G, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Med. 2013 Feb;14(2):180-229. (Context for neuropathic pain)

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome