Compression fracture of the spine

- Understanding Spinal Compression Fractures

- Symptoms of Spinal Compression Fractures

- Diagnosis of Spinal Compression Fractures

- Complications of Spinal Compression Fractures

- Treatment of Spinal Compression Fractures

- Differential Diagnosis of Acute Back Pain

- Prevention and Long-Term Outlook

- When to Seek Medical Attention

- References

Understanding Spinal Compression Fractures

Definition and Common Causes

A compression fracture of the spine (vertebral compression fracture - VCF) is a common type of spinal injury where one or more vertebral bodies collapse or become wedged, leading to a decrease in their height. This pathology is quite prevalent in modern society and can be caused by a variety of factors, primarily:

- Trauma:

- High-energy trauma: Such as car accidents, falls from a significant height, or sports injuries.

- Axial loading injuries: For example, diving into shallow water and hitting the head can transmit strong compressive forces to the cervical or thoracic spine.

- Osteoporosis: Weakening of the bones due to decreased bone density makes vertebrae susceptible to fracture even with minor trauma or sometimes spontaneously during routine activities like bending or coughing. This is the most common cause of VCFs, especially in older adults and postmenopausal women.

- Pathological Fractures: Underlying bone diseases such as primary bone tumors, metastatic cancer to the spine, infections (spondylitis), or certain metabolic bone disorders can weaken the vertebrae and lead to fractures with minimal or no trauma.

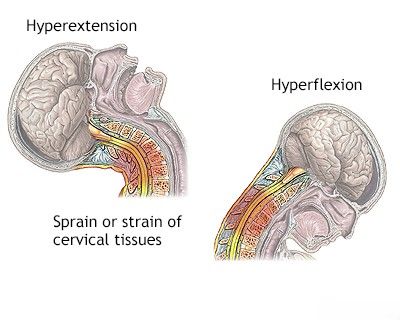

This illustration depicts the mechanism of a compression fracture of vertebral bodies, often accompanied by a concomitant whiplash-type stretching injury to the muscles and ligaments of the cervical spine, especially in traumatic events.

Complicated vs. Uncomplicated Fractures

Spinal compression fractures can be classified as complicated or uncomplicated:

- Uncomplicated Compression Fracture: In this scenario, the vertebral body collapses, but there is no significant displacement of bone fragments into the spinal canal, and thus no direct injury or compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots. The primary symptom is usually local back pain or a feeling of discomfort in the acute period of the injury. Radiographic examination typically reveals a decrease in the height of the vertebral body (often a wedge shape). Occasionally, free bone fragments, a fracture line involving the vertebral arch, or a fracture of the spinous process may be detected. The pain in uncomplicated fractures arises from irritation of sensitive nerve endings in the damaged bone, periosteum, and surrounding soft tissues. During the course of the disease (healing), these pains usually subside and disappear as the patient fully recovers, although some residual deformity may remain.

- Complicated Compression Fracture: This type involves displacement of bone fragments posteriorly into the spinal canal, leading to compression of the spinal cord or cauda equina. This results in neurological symptoms in addition to back pain (see Complications section). Burst fractures, where the vertebral body shatters and fragments are retropulsed, are a common type of complicated fracture.

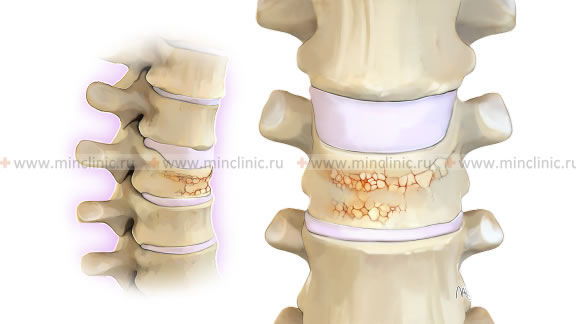

This image illustrates compression fractures of the vertebral bodies in the cervical spine, complicated by compression of the spinal cord due to posterior displacement of bone fragments.

Osteoporosis-Related Compression Fractures

Compression fractures of the spine often occur in individuals with osteoporosis, particularly elderly people. In such cases, even minimal trauma, such as falling from a small height, bending, lifting a light object, or even forceful coughing or sneezing, can be sufficient for a vertebral body to flatten and decrease in height. These fractures may not always be diagnosed immediately, as they might not cause severe acute pain or significant inconvenience to the patient initially. They are sometimes detected accidentally during X-ray examinations performed for other reasons. However, multiple osteoporotic VCFs can lead to progressive kyphosis (dowager's hump), height loss, chronic pain, and impaired pulmonary function.

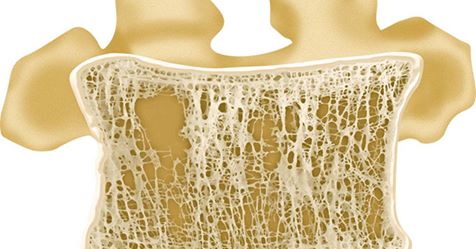

A frontal section of a vertebral body revealing osteoporosis of the spongy (trabecular) bone substance, which weakens the vertebra and predisposes it to compression fractures.

An X-ray image demonstrating a compression fracture of a thoracic vertebral body, visible as a decrease in its anterior height (wedging).

Symptoms of Spinal Compression Fractures

The symptoms of a spinal compression fracture can vary widely depending on the cause, severity, and location of the fracture, and whether neural elements are involved.

- Back Pain: This is the most common symptom. The pain can range from mild to severe and is often localized to the area of the fracture. It may be sudden in onset after trauma or gradual in osteoporotic fractures. The pain is typically worse with weight-bearing activities (standing, walking) and axial loading, and may be relieved by lying down.

- Tenderness: Palpation or percussion over the spinous process of the fractured vertebra usually elicits tenderness.

- Limited Spinal Mobility: Stiffness and reduced range of motion in the affected spinal segment due to pain and muscle spasm.

- Deformity: Multiple compression fractures can lead to progressive height loss and the development of kyphosis (forward curvature of the spine), often seen as a "dowager's hump" in the thoracic spine in elderly individuals with osteoporosis.

- Neurological Symptoms (if complicated): If the fracture causes compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots, symptoms may include:

- Radiating pain (radiculopathy) into the arms or legs.

- Numbness, tingling (paresthesia).

- Muscle weakness.

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction (in severe cases, indicating cauda equina syndrome or significant cord compression – a neurological emergency).

- Gait disturbance or balance problems.

- Asymptomatic Fractures: Some osteoporotic compression fractures, especially if mild, may cause minimal or no pain and are discovered incidentally on imaging.

Diagnosis of Spinal Compression Fractures

The diagnosis of a spinal compression fracture with a decrease in vertebral body height typically begins with a clinical evaluation by a physician, followed by imaging studies.

Clinical Examination

A thorough neurological and orthopedic examination is performed. This includes assessing for localized spinal tenderness, evaluating range of motion, checking for any neurological deficits (motor strength, sensation, reflexes), and observing for spinal deformities.

Imaging Studies

Based on the results of the consultation and clinical examination, the following additional diagnostic procedures may be prescribed:

- Radiography (X-ray) of the Spine: Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views are standard initial imaging tests. X-rays can readily identify most compression fractures, showing a decrease in vertebral body height (often wedge-shaped anteriorly) and assessing overall spinal alignment.

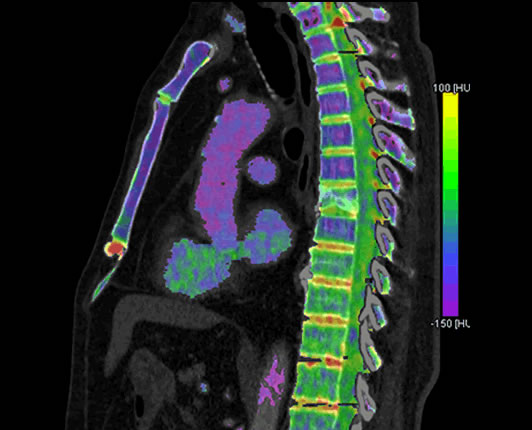

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan of the Spine: Provides more detailed images of bony structures than X-rays. CT is particularly useful for:

- Evaluating the extent and comminution of the fracture.

- Assessing for involvement of the posterior vertebral wall and potential encroachment on the spinal canal (retropulsion of fragments).

- Detecting fractures of the posterior elements (pedicles, lamina, facets).

- A dual-energy CT scan of the spine can sometimes provide additional information by virtually "subtracting" calcium, which may help in distinguishing an old (healed) compression fracture from a new (acute) one by highlighting bone marrow edema in acute fractures. For example, in a patient with a history of small cell lung cancer (a risk factor for metastases), detecting signal amplification at the site of bone marrow edema could suggest an acute or pathological fracture.

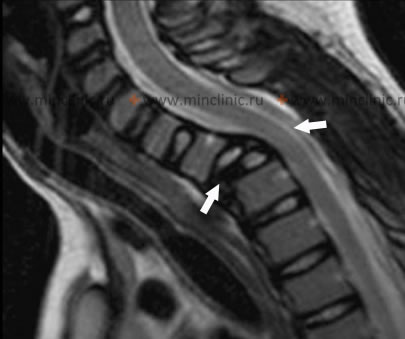

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Spine: MRI is the best modality for visualizing soft tissues, including the spinal cord, nerve roots, intervertebral discs, and ligaments. It is crucial for:

- Assessing for spinal cord or nerve root compression.

- Detecting ligamentous injury.

- Evaluating the acuity of the fracture (bone marrow edema on STIR or T2-weighted fat-suppressed sequences indicates an acute or subacute fracture).

- Differentiating osteoporotic fractures from pathological fractures due to tumor (metastasis, myeloma), as tumors often have characteristic signal intensities and enhancement patterns.

On this MRI of the cervical spine, a compression fracture of a vertebral body is visible, which is complicated by compression of the spinal cord (indicated by arrows).

Bone Density Measurement (Densitometry)

If an osteoporotic fracture is suspected, or in individuals at risk for osteoporosis, a bone mineral density (BMD) test, most commonly Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA or DEXA scan), is performed. This procedure measures bone density, typically at the hip and lumbar spine, to diagnose osteoporosis and assess fracture risk.

Complications of Spinal Compression Fractures

Neurological Complications

Complicated compression fractures of the spine, where bone fragments are displaced into the spinal canal causing compression of the spinal cord or cauda equina, are accompanied by neurological disorders in addition to local pain at the fracture site. These can include:

- Motor Deficits: Weakness (paresis) or paralysis (plegia) in the limbs below the level of injury.

- Sensory Deficits: Numbness, tingling, or loss of sensation below the level of injury.

- Bowel and Bladder Dysfunction: Urinary retention or incontinence, fecal incontinence (particularly with cauda equina syndrome or severe cord compression).

- Impaired Conducting and Regulating Functions of the Spinal Cord.

These are particularly difficult cases that can lead to severe disability and, in some instances with very high cervical injuries or severe systemic compromise, can even be life-threatening.

Pressure Sores (Decubitus Ulcers)

Pressure sores are a significant secondary consequence of spinal compression fractures that lead to spinal cord compression and resultant immobility. They occur as a result of prolonged pressure on the skin and underlying tissues, typically over bony prominences, in immobilized patients (e.g., those lying on their back for extended periods). Neurotrophic dysfunction (impaired tissue nutrition and healing due to nerve damage) below the level of spinal cord injury greatly slows down the healing process in areas of necrosis, making bedsores difficult to treat and prone to infection.

Neurotrophic pressure sores (bedsores) are a serious consequence of impaired innervation and immobility following a compression fracture of the spine that results in compression of the spinal cord.

Chronic Pain and Deformity

- Chronic Pain: Persistent pain at the fracture site or radicular pain can become chronic.

- Spinal Deformity: Progressive kyphosis (forward rounding of the back), particularly with multiple thoracic compression fractures, can lead to height loss, restrictive lung disease, and altered body mechanics.

- Spinal Stenosis: Narrowing of the spinal canal can develop over time due to fracture healing or progressive deformity.

- Pseudoarthrosis: Non-union of the fracture, leading to persistent pain and instability.

Treatment of Spinal Compression Fractures

The treatment approach for spinal compression fractures depends on the cause, severity, stability of the fracture, presence of neurological deficits, and the patient's overall health.

Conservative Treatment

Conservative treatment is often appropriate for stable, uncomplicated compression fractures, particularly those due to osteoporosis, with minimal pain or deformity and no neurological compromise. It includes:

- Pain Management: Analgesics (acetaminophen, NSAIDs), muscle relaxants. Calcitonin (e.g., intranasal spray "Miakaltsik") is sometimes recommended, especially for osteoporotic VCFs, as it may have an analgesic effect and can inhibit osteoclast activity.

- Rest: A period of bed rest or activity modification during the acute painful period.

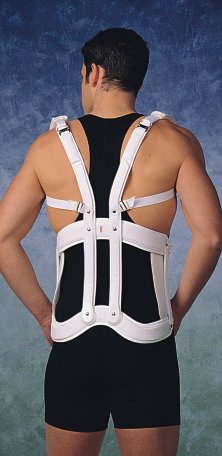

- Bracing: Wearing a special spinal brace (orthosis) to provide support, limit motion, and reduce pain. Extension braces (hyperextension braces) are often used for thoracic or lumbar compression fractures to help straighten the spine at the fracture site and provide axial fixation. The duration of brace wear averages from 1.5 to 2 months from the moment of the spinal fracture, depending on healing and symptoms.

- Physiotherapy (Physical Therapy): Once acute pain subsides, a carefully graded exercise program is initiated to improve posture, strengthen paraspinal and core muscles, and increase mobility. Modalities like UHF, SMT (Segmental Myofascial Therapy, or other specific regional techniques), TENS, etc., may be used for pain relief.

- Treatment of Underlying Osteoporosis: Essential for osteoporotic VCFs. Includes calcium and vitamin D supplementation, and antiresorptive or anabolic medications (e.g., bisphosphonates, denosumab, teriparatide).

Wearing an extensor (hyperextension) brace is a common component in the conservative treatment of a compression fracture of the spine, particularly when there is a decrease in the height of the vertebral body, to promote alignment and stability.

This image shows another perspective of an extensor (hyperextension) brace used in the treatment of a compression fracture of the spine involving a reduction in vertebral body height, aiming to support healing and maintain spinal alignment.

Surgical Treatment (Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty)

Surgical treatment for compression fractures of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae (typically Th5 to L5) with a significant decrease in vertebral body height and persistent pain may involve minimally invasive procedures aimed at restoring vertebral body height (partially or fully) and stabilizing the fracture. These are primarily used for painful osteoporotic or some pathological VCFs unresponsive to conservative care.

- Vertebroplasty: Involves injecting medical-grade bone cement (polymethylmethacrylate - PMMA) under imaging guidance (fluoroscopy or CT) directly into the fractured vertebral body to stabilize it and relieve pain. It does not aim to restore vertebral height.

- Kyphoplasty (Balloon Vertebroplasty): A balloon catheter is first inserted into the fractured vertebra and inflated to create a cavity and potentially restore some vertebral body height. The balloon is then removed, and the cavity is filled with bone cement. This procedure aims to stabilize the fracture, relieve pain, and correct some deformity.

More extensive surgical intervention (e.g., decompression with fusion and instrumentation) may be required for:

- Complicated fractures with neurological deficits due to spinal cord or nerve root compression.

- Gross spinal instability.

- Significant progressive deformity.

- Pathological fractures due to tumors requiring excision and stabilization.

Pharmacological Management

In addition to analgesics, specific medications may be used:

- Calcitonin: As mentioned (e.g., "Miakaltsik" intranasal spray), it can have an analgesic effect in acute osteoporotic VCFs and may inhibit bone resorption.

- Bisphosphonates and other anti-osteoporotic drugs: Essential for treating underlying osteoporosis to prevent further fractures.

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Back Pain

Sudden onset of back pain, especially after minor trauma or in at-risk individuals, should prompt consideration of a compression fracture. However, other conditions can cause acute back pain:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Spinal Compression Fracture | Often history of trauma (can be minor in osteoporosis), sudden onset of localized back pain, tenderness over spinous process. X-ray/CT/MRI confirms vertebral body height loss. |

| Acute Lumbar Disc Herniation | Sudden onset of low back pain, often with radiating leg pain (sciatica), numbness, weakness. Pain often worse with sitting, bending, coughing. MRI diagnostic. |

| Musculoskeletal Strain/Sprain (Acute Lumbago) | Often related to lifting or twisting. Diffuse muscle pain and spasm. Neurological exam usually normal. No fracture on imaging. |

| Facet Joint Syndrome (Acute Flare) | Localized back pain, often worse with extension or twisting. May refer pain to buttock/thigh. |

| Spinal Metastasis / Pathological Fracture | History of cancer. Pain often insidious, worse at night, not relieved by rest. May have constitutional symptoms. Imaging shows lytic or blastic lesion with fracture. |

| Spinal Infection (e.g., Discitis, Vertebral Osteomyelitis) | Severe localized pain, fever, elevated inflammatory markers. MRI diagnostic. |

Prevention and Long-Term Outlook

Prevention of osteoporotic compression fractures involves:

- Screening for and treating osteoporosis.

- Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake.

- Regular weight-bearing exercise.

- Fall prevention strategies in the elderly.

Prevention of traumatic VCFs involves safety measures to avoid high-impact injuries.

The long-term outlook for uncomplicated VCFs treated conservatively is generally good in terms of pain relief, although some vertebral deformity may persist. For fractures treated with vertebroplasty/kyphoplasty, pain relief is often rapid and significant. Complicated fractures with neurological deficits have a more variable prognosis depending on the severity of neural injury and the success of decompression and stabilization.

When to Seek Medical Attention

Medical attention should be sought if:

- Severe back pain occurs after a fall or trauma, however minor (especially in individuals with osteoporosis or known cancer).

- Back pain is sudden, severe, and incapacitating.

- There are any neurological symptoms such as radiating pain, numbness, weakness in the legs, or bowel/bladder dysfunction.

- Back pain is accompanied by unexplained fever or weight loss.

- The individual has known osteoporosis and develops new, significant back pain.

Prompt evaluation and diagnosis are important to ensure appropriate treatment and prevent long-term complications.

References

- Old JL, Calvert M. Vertebral compression fractures in the elderly. Am Fam Physician. 2004 Jan 1;69(1):111-6.

- Alexandru D, So W. Evaluation and Management of Vertebral Compression Fractures. Perm J. 2012 Fall;16(4):46-51.

- Gold DT, Silverman SL. The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a review of the literature. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2004 Jun;2(2):47-51.

- Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 6;361(6):569-79.

- Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 6;361(6):557-68.

- Denis F. The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983 Nov-Dec;8(8):817-31.

- Vaccaro AR, Lehman RA Jr, Hurlbert RJ, et al. A new classification of thoracolumbar injuries: the importance of injury morphology, the integrity of the posterior ligamentous complex, and neurologic status. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005 Oct 15;30(20):2325-33.

- Kim DH, Vaccaro AR. Osteoporotic compression fractures of the spine; current options and considerations for treatment. Spine J. 2006 Sep-Oct;6(5):479-87.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome