Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

Understanding Coccygodynia (Tailbone Pain)

Coccygodynia, commonly referred to as tailbone pain, is a medical term describing persistent or paroxysmal (occurring in episodes) pain localized to the coccyx (the small triangular bone at the very end of the spine). This condition can be quite debilitating, significantly affecting daily activities like sitting and standing up.

Definition and Prevalence

Coccyx pain occurs more frequently in females than in males. This gender predilection is partly attributed to anatomical differences: the coccyx in women is generally more mobile relative to the sacrum compared to men, and it is more exposed and susceptible to injury, particularly during childbirth. The increased mobility in women is linked to its role in facilitating the birthing process.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Coccygodynia can arise from a variety of causes, primarily involving traumatic or inflammatory damage to the coccyx itself, or to the surrounding sacral and coccygeal nerve plexuses. Potential etiological factors include:

- Direct Trauma: This is the most common cause. A fall directly onto the buttocks (impacting the coccyx), a direct blow to the tailbone, or injuries sustained during contact sports can lead to bruising, fracture, or dislocation of the coccyx.

- Repetitive Strain or Pressure: Prolonged sitting on hard or poorly designed surfaces, or activities like cycling or horseback riding, can cause chronic irritation and inflammation of the coccyx and surrounding tissues.

- Childbirth: The passage of the baby through the birth canal can strain or injure the coccyx, particularly during difficult deliveries or if forceps or vacuum extraction are used.

- Degenerative Joint Disease: Osteoarthritis of the sacrococcygeal joint.

- Inflammatory Conditions: Less commonly, inflammatory arthritis or infections can affect the coccyx.

- Nerve Plexus Irritation: Inflammation or irritation of the sacral and coccygeal nerve plexuses that supply sensation to the region.

- Referred Pain: Pain in the coccyx region can sometimes be referred from diseases of nearby organs or structures, including:

- Pelvic bones

- Rectum (e.g., proctitis, hemorrhoids, anal fissures)

- Pelvic soft tissues and pelvic floor muscles (e.g., levator ani syndrome, myofascial pain)

- Lumbosacral spine disorders (e.g., disc herniation affecting lower sacral nerves)

- Neoplasms: Rarely, tumors (benign or malignant) in the sacrococcygeal region, such as chordomas, can cause coccyx pain.

- Idiopathic Coccygodynia: In some cases, no clear cause can be identified.

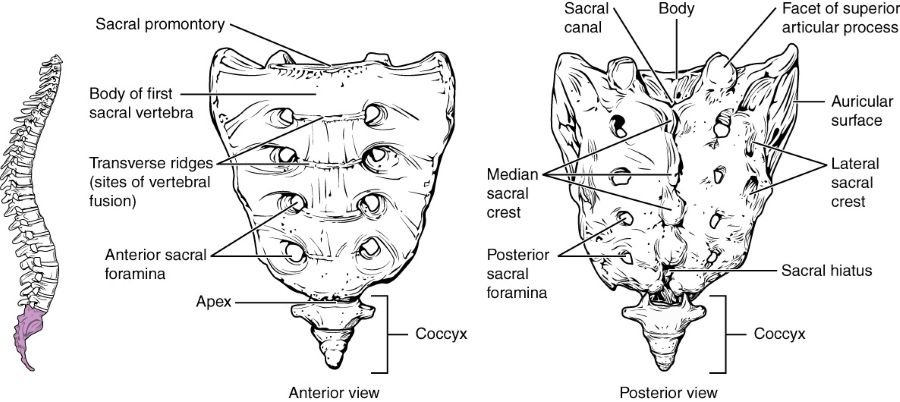

The sacrum is formed from the fusion of five sacral vertebrae, whose lines of fusion are indicated by the transverse ridges. The fused spinous processes form the median sacral crest, while the lateral sacral crest arises from the fused transverse processes. The coccyx is formed by the fusion of four small coccygeal vertebrae.

Clinical Picture and Emotional Impact

The clinical picture of coccygodynia is characterized by pain that is either constant or occurs in episodes (paroxysmal), localized directly to the coccyx region. The pain typically intensifies with:

- Sitting, especially on hard surfaces or for prolonged periods.

- Transitioning from a sitting to a standing position.

- Defecation, due to pressure on the coccyx from the rectum.

- Sexual intercourse (in some cases).

The pain often radiates to the perineum, gluteal (buttock) region, genitals, or the inner aspects of the thighs. The character of the pain in the tailbone can be aching, burning, or boring (a deep, gnawing sensation). It sharply limits the physical activity of patients and makes sitting particularly uncomfortable or unbearable.

Upon examination, direct pressure on the coccyx or movement of the coccyx (e.g., during a digital rectal examination) usually elicits significant tenderness. In some instances of traumatic coccygodynia, the pain may resolve spontaneously over time, which can be explained by the resorption of a hematoma and the healing of minor scar tissue. However, in most cases, coccygodynia tends to be a persistent and long-standing condition, with periods of remission often replaced by exacerbations.

Wearing a sacral belt can sometimes help in the treatment of pain in the sacrum associated with sacroiliitis or sacroiliac joint arthrosis, particularly noted in pregnant women where pelvic girdle pain can sometimes be confused with or coexist with coccygodynia.

It is possible that patients suffering from coccygodynia represent a significant portion of individuals patiently seeking an effective diagnosis and treatment, often visiting multiple specialists and sometimes finding temporary "comfort" or misdirection after consulting psychiatrists or alternative practitioners if the organic cause is not clearly identified. The diagnostic challenge arises because representatives of various medical specialties, when focusing on the zone of pain radiation, may identify incidental or minor pathological changes in organs within the pelvic cavity (e.g., minor coccygeal deviation or hypermobility, hemorrhoids, uterine retroversion, residual effects of pelvic inflammatory disease, mild pelvic organ prolapse) which may or may not be the true source of the coccygeal pain.

Given that the condition of the pelvic organs and chronic pelvic pain can significantly influence a patient's emotional background, depressive reactions, anxiety, and frustration are often obligatory companions of persistent coccygodynia syndrome.

Diagnosis of Coccygodynia (Tailbone Pain)

A thorough diagnostic evaluation is essential for coccygodynia to identify the underlying cause and rule out other conditions. This typically involves:

Physical Examination

- External Palpation: Direct pressure over the coccyx externally will usually reproduce the patient's pain. The physician will assess for tenderness, swelling, or any deformity.

- Digital Rectal Examination (DRE): The presence of pain in the coccyx area often necessitates a digital examination of the rectum. Objectively, when examining with a finger through the rectum (per rectum), significant tenderness in the coccyx area is almost always found. Painful compaction, sometimes in the form of a radial cord-like structure, may be palpated along the posterior sector during the examination. Pressure on this cord typically results in a significant increase in pain in the coccyx. Patients often describe this pain as deep, "acting on the nerves," or "boring." Sometimes it is possible to palpate the painful sacrospinous ligament, which may feel like a very tight cord. Movement of the coccyx during DRE (gentle flexion and extension) can also reproduce the pain and assess for hypermobility or instability of the sacrococcygeal joint.

- Pelvic Floor Muscle Assessment: Palpation of the pelvic floor muscles (e.g., levator ani, coccygeus) may reveal hypertonicity, spasm, or trigger points, which can contribute to or result from coccygodynia.

- Neurological Examination: To rule out lumbosacral radiculopathy or other neurological causes of referred pain.

The pathogenesis of some forms of coccygodynia syndrome is thought to be caused by local spasm of a part of the perineal musculature (e.g., coccygeus muscle, levator ani) and shortening or tension in the pelvic ligaments (e.g., sacrospinous, sacrotuberous ligaments). Local hypertonicity of these perineal muscles does not necessarily represent a unique feature in its origin; it often arises according to the general principles of trigger point formation in skeletal muscles due to trauma, overuse, or chronic strain. In an isolated form, hypertonicity of these muscles can create the appearance of an independent disease that may not fit neatly into the framework of classical diseases of the pelvic organs.

Imaging and Other Investigations

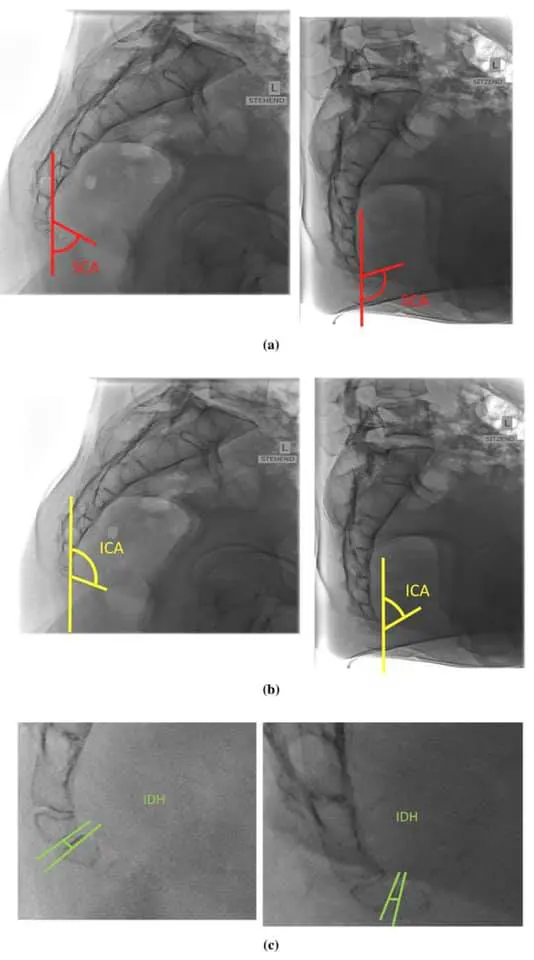

- X-ray of the Sacrococcygeal Spine: Anteroposterior and lateral views of the sacrum and coccyx are performed. Dynamic X-rays, taken in both standing and sitting positions, can be particularly useful to assess for coccygeal instability (hypermobility or subluxation) or abnormal angulation during weight-bearing. X-rays can also reveal fractures, dislocations, arthritic changes, or bony spicules.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: These may be indicated if X-rays are inconclusive, if a tumor or infection is suspected, or to evaluate surrounding soft tissues, nerve plexuses, or lumbosacral spine pathology that might refer pain to the coccyx.

- Local Anesthetic Injection: Injecting a small amount of local anesthetic into the painful area around the coccyx (e.g., sacrococcygeal joint, pericoccygeal tissues, or specific trigger points) can be diagnostic. Significant pain relief after the injection supports the coccyx as the source of pain.

- Other Examinations (to rule out referred pain): If indicated by history or examination, further investigations such as sigmoidoscopy (to examine the rectum and lower colon), orthopedic evaluation of the lumbosacral spine and pelvis, urological assessment, or gynecological examination may be necessary to exclude diseases of nearby organs that could be causing or contributing to the pain.

In addition to a digital rectal examination for coccygodynia (pain in the coccyx), an X-ray of the sacrococcygeal spine is also commonly performed to evaluate for fractures, dislocations, or degenerative changes.

Dynamic X-rays taken in both standing and sitting positions can be valuable in assessing patients with coccygodynia, as they may reveal instability or abnormal movement of the coccyx during weight-bearing that contributes to pain.

Treatment of Coccygodynia (Tailbone Pain)

The treatment for coccygodynia is primarily conservative and aims to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, and improve function. A multimodal approach is often most effective.

Conservative Management

- Activity Modification: Avoiding activities that exacerbate pain, such as prolonged sitting or sitting on hard surfaces.

- Cushions: Using specialized coccyx cushions (wedge-shaped or donut-shaped with a cutout for the tailbone) can significantly relieve pressure on the coccyx when sitting.

- Postural Advice: Maintaining good posture while sitting (e.g., sitting upright with lumbar support, feet flat on the floor).

- Heat and Cold Therapy: Applying ice packs to reduce acute inflammation and pain, or warm compresses to relax muscles and soothe chronic discomfort.

Pharmacological Therapy

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Oral NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) or topical NSAID creams/gels can help reduce pain and inflammation.

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen (paracetamol) for pain relief.

- Muscle Relaxants: If significant pelvic floor muscle spasm is present.

- Neuropathic Pain Medications: If nerve irritation is a component (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants).

- Stool Softeners: To prevent constipation and straining during defecation, which can aggravate coccyx pain.

- Neuropsychotropic Drugs: In cases where pain in the coccyx is significantly impacting the patient's emotional well-being, or if a strong psychosomatic component (like depression or anxiety) is contributing to pain perception, neuropsychotropic medications (e.g., antidepressants, anxiolytics) may be prescribed by a psychiatrist or appropriate specialist to help weaken the negative emotional background and improve coping.

In the treatment of pain in the coccyx (coccygodynia), physiotherapy modalities can help accelerate the elimination of swelling (puffiness) and inflammation, alleviate soreness, and restore range of motion in the sacrococcygeal region and surrounding pelvic floor muscles.

Interventional Pain Management (Injections/Blockades)

If pain is severe or unresponsive to conservative measures, therapeutic injections may be considered:

- Local Anesthetic and Corticosteroid Injections: Injections into the sacrococcygeal joint, around the coccyx, into pericoccygeal ligaments, or into specific trigger points in the pelvic floor muscles (e.g., with lidocaine/novocaine and a corticosteroid like hydrocortisone, diprospan/betamethasone, or Kenalog/triamcinolone) can provide significant pain relief by reducing inflammation and blocking pain signals. These are often performed under imaging guidance (fluoroscopy or ultrasound).

- Ganglion Impar Block: A nerve block targeting the ganglion impar (a sympathetic ganglion located anterior to the sacrococcygeal junction) can be effective for some types of chronic coccygeal pain.

- Radiofrequency Ablation: In refractory cases, radiofrequency ablation of nerves supplying the coccyx has been explored.

Manual Therapy and Physiotherapy

- Manual Therapy: Techniques performed by a qualified physical therapist, osteopath, or chiropractor are mandatory if there are no contraindications. This can include:

- Mobilization or manipulation of the coccyx (externally or internally via the rectum) to correct malalignment or improve mobility of the sacrococcygeal joint.

- Soft tissue mobilization and myofascial release of tight pelvic floor muscles (e.g., levator ani, coccygeus) and surrounding ligaments.

- Post-isometric relaxation (PIR) techniques for pelvic floor muscles, which serve not only as a therapeutic but also as a diagnostic technique, often relieving the patient's fear of the unknown by demonstrating a non-pharmacological way to influence their pain.

- Physiotherapy Modalities: Application of heat, cold, ultrasound, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), UHF (Ultra-High Frequency) therapy, CMT (Sinusoidal Modulated Currents), or infrared radiation therapy to the coccygeal region can help reduce pain and inflammation.

- Exercise Therapy: Stretching and strengthening exercises for the pelvic floor, gluteal, and core muscles. Postural correction exercises.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture may be used as an adjunctive therapy to help manage pain in some individuals with coccygodynia.

Surgical Treatment (Coccygectomy - Rare)

Surgical removal of the coccyx (coccygectomy) is considered a last resort and is reserved for a small percentage of patients with severe, intractable coccygodynia that has failed to respond to all forms of comprehensive conservative and interventional management for an extended period (e.g., >6 months). The decision for surgery requires careful patient selection and thorough preoperative evaluation to confirm that the coccyx is indeed the primary source of pain. While it can provide relief for some, success rates vary, and potential complications exist.

Depending on the severity of pain manifestations, a combination of the following therapeutic actions is often employed: drug therapy (NSAIDs, analgesics, hormones if indicated for underlying conditions), therapeutic injections (into sacroiliac joints, spinal canal if related to referred pain, or trigger points in muscles), manual therapy (muscle, articular, and radicular techniques), physiotherapy, and acupuncture.

Differential Diagnosis of Coccydynia

Pain in the coccygeal region is not always due to direct coccyx pathology. A thorough differential diagnosis is important:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Coccygodynia (Primary) | Pain localized to coccyx, worse with sitting, rising, defecation. Tenderness on palpation of coccyx externally or via DRE. Dynamic X-rays may show instability/hypermobility. |

| Lumbosacral Radiculopathy (e.g., S2-S4 roots) | Pain may radiate to perineum/coccyx but often associated with low back pain and other neurological signs (sensory changes, reflex loss) in a dermatomal pattern. SLR may be positive. |

| Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction/Arthritis | Pain often over SI joint, buttock, may refer to groin or posterior thigh, but typically not directly over coccyx tip. Positive SI joint provocative tests. |

| Piriformis Syndrome | Buttock pain, may radiate down leg (sciatica-like). Tenderness over piriformis muscle. Pain with specific hip movements. Coccyx usually not primary tender point. |

| Pelvic Floor Myofascial Pain / Levator Ani Syndrome | Deep pelvic ache, rectal pressure, pain with sitting. Tender trigger points in pelvic floor muscles on DRE or vaginal exam. Coccyx may be secondarily tender. |

| Pilonidal Sinus/Cyst (infected) | Pain, swelling, redness, drainage in the sacrococcygeal cleft (natal cleft). Visible sinus opening or abscess. |

| Proctalgia Fugax | Sudden, severe, episodic rectal pain lasting seconds to minutes, then resolves completely. Coccyx not typically tender between episodes. |

| Perianal Conditions (e.g., Anal Fissure, Hemorrhoids, Perianal Abscess) | Pain often related to defecation, bleeding, itching. Specific findings on anoscopy/proctoscopy. |

| Gynecological Conditions (in females) | Endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian cysts. Pain often cyclical or associated with other gynecological symptoms. Pelvic exam findings. |

| Urological Conditions (in males) | Prostatitis. Pain often in perineum, pelvis, with urinary symptoms. |

| Tumors (rare - e.g., Chordoma, Sacrococcygeal Teratoma) | Persistent, progressive pain, may have palpable mass. Neurological deficits if advanced. Requires imaging (MRI/CT) and biopsy. |

Prognosis and Prevention

The prognosis for coccygodynia is generally good with conservative treatment, with many patients experiencing significant relief. However, it can sometimes become a chronic and frustrating condition.

Preventive measures include:

- Using appropriate cushioning when sitting for long periods, especially on hard surfaces.

- Avoiding direct trauma to the tailbone.

- Maintaining good posture.

- Strengthening core and pelvic floor muscles.

When to Seek Medical Attention

It is advisable to seek medical attention for tailbone pain if:

- The pain is severe or does not improve with self-care measures after a few days/weeks.

- The pain started after a significant trauma or fall.

- There are associated symptoms like fever, unexplained weight loss, persistent numbness or weakness in the legs, or changes in bowel/bladder function (which could indicate a more serious underlying condition).

- The pain significantly interferes with daily activities and quality of life.

A healthcare professional can help determine the cause of the pain and recommend an appropriate treatment plan.

References

- Lirette LS, Chaiban G, Tolba R, Christo PJ. Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner J. 2014 Spring;14(1):84-7.

- Foye PM. Coccydynia: a comprehensive review. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2011 Aug;22(3):505-20.

- Nathan ST, Fisher BE, Roberts CS. Coccydynia: a review of pathoanatomy, etiology, treatment and outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Dec;92(12):1622-7.

- Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000 Dec 1;25(23):3072-9.

- Foye PM, Buttaci CJ, Stitik TP, Yonclas PP. Successful injection for coccydynia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006 Sep;85(9):783-8.

- Hodges SD, Eck JC, Humphreys SC. A treatment and outcomes analysis of patients with coccydynia. Spine J. 2004 Mar-Apr;4(2):138-40.

- Patel R, Appannagari A, Whang PG. Coccydynia. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008 Dec;1(3-4):223-6.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome