Malignant bone disease (osteosarcoma)

Malignant Bone Disease & Osteosarcoma: Overview

Understanding the fundamental structure of bone tissue is crucial for comprehending the mechanisms underlying malignant bone diseases, including primary tumors like osteosarcoma and metastatic disease [1].

Bone is a specialized connective tissue comprising cells and an extracellular matrix [1]. The extracellular matrix consists of:

- Organic component (Osteoid): Primarily Type I collagen (~90-95%), providing tensile strength, along with non-collagenous proteins (e.g., osteocalcin, osteonectin) involved in mineralization and regulation [1].

- Inorganic component: Mainly calcium phosphate crystals (hydroxyapatite), providing hardness and rigidity [1].

Bone cells include osteoblasts (bone-forming), osteocytes (mature cells sensing mechanical load), and osteoclasts (bone-resorbing) [1].

Pathophysiology of Bone Involvement by Tumors

Normal bone undergoes continuous remodeling, a balance between resorption by osteoclasts and formation by osteoblasts [1, 2]. Malignant processes disrupt this balance [2, 3].

- Direct Invasion/Destruction: Primary bone tumors (like osteosarcoma) or metastatic tumors directly destroy bone tissue [3].

- Stimulation of Osteoclasts: Many tumors (especially metastases from breast, lung, kidney cancer; multiple myeloma; lymphomas) secrete factors like cytokines (e.g., RANKL, interleukins) or growth factors that stimulate osteoclast activity [2, 3]. This leads to excessive local bone resorption (osteolysis), weakening the bone.

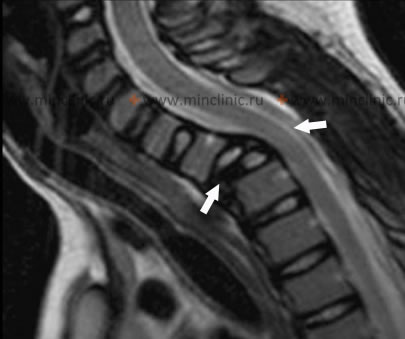

This accelerated bone resorption is a key mechanism leading to complications like pathological fractures (fractures occurring with minimal or no trauma due to weakened bone) and pain [2, 3]. Vertebral bodies are common sites for metastases and myeloma, and pathological compression fractures here can cause spinal cord or nerve root compression, representing neurological emergencies [3].

Multiple myeloma, a cancer of plasma cells, is a frequent cause of osteolytic lesions and pathological fractures, sometimes requiring urgent surgical stabilization [3].

Hypercalcemia of Malignancy

Hypercalcemia (high blood calcium) is a common metabolic complication of malignancy [2, 3]. There are two main mechanisms:

- Osteolytic Hypercalcemia: Caused by extensive bone destruction from metastases or myeloma releasing calcium into the blood. Cytokines released by tumor cells stimulate local osteoclast activity [2, 3].

- Humoral Hypercalcemia of Malignancy (HHM): Certain solid tumors (e.g., squamous cell carcinomas of lung, head/neck; renal, bladder, ovarian cancers; less commonly osteosarcoma itself, though some sarcomas can produce it) secrete Parathyroid Hormone-related Peptide (PTHrP) [2, 3]. PTHrP mimics the action of PTH on bone (increasing resorption) and kidney (increasing calcium reabsorption), leading to hypercalcemia [2]. Importantly, PTHrP is structurally different from PTH and is not detected by standard PTH immunoassays; thus, in HHM, PTH levels are appropriately suppressed by the high calcium [2]. Other humoral factors like cytokines can also contribute [2].

Differential Diagnosis of Destructive Bone Lesions / Hypercalcemia

| Condition | Typical Bone Findings | Key Features / Lab Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma (Primary Malignant) | Aggressive destructive lesion, often mixed lytic/sclerotic, periosteal reaction (Codman's triangle, sunburst), soft tissue mass. Typically metaphysis of long bones (knee common). | Typically adolescents/young adults. Bone pain, swelling. Alk Phos often elevated. Biopsy confirms malignant osteoid production. Hypercalcemia less common (unless HHM variant). |

| Bone Metastases | Often multiple lesions. Can be lytic (e.g., lung, kidney, thyroid), blastic (e.g., prostate, breast [can be mixed]), or mixed. Common in spine, pelvis, ribs, proximal long bones. | Older adults usually. History of primary cancer. Bone pain, pathological fractures. Hypercalcemia common (osteolytic or HHM). PTH suppressed if hypercalcemic. Bone scan often positive (except myeloma). Biopsy confirms metastatic carcinoma. |

| Multiple Myeloma | Multiple "punched-out" lytic lesions (skull, spine, long bones). Diffuse osteopenia. Pathological fractures common. | Bone pain, fatigue, anemia, renal failure. Hypercalcemia common (osteolytic). PTH suppressed. Serum/urine protein electrophoresis (M-spike), free light chains abnormal. Bone marrow biopsy diagnostic (plasma cells). Bone scan often *negative*. |

| Primary Hyperparathyroidism | Generalized osteopenia, subperiosteal resorption (esp. phalanges), "salt & pepper" skull, brown tumors (osteitis fibrosa cystica - rare now). Pathological fractures possible. | High PTH, High Calcium, Low/Normal Phosphate. Often asymptomatic hypercalcemia, kidney stones. Parathyroid imaging identifies source. |

| Paget's Disease of Bone | Focal areas of disordered remodeling: lytic phase (osteoporosis circumscripta), mixed phase, sclerotic phase. Bone expansion, bowing deformities, cortical thickening. | Often asymptomatic. Bone pain, fractures, deafness possible. Markedly elevated Alk Phos. Normal Ca, Phos, PTH. X-ray/Bone scan characteristic. |

| Osteomyelitis | Focal bone destruction (lysis), periosteal reaction, sequestrum/involucrum (chronic). Often localized pain, swelling, fever. | Elevated WBC, ESR/CRP. Blood/bone cultures positive. MRI most sensitive early. X-ray changes lag. Bone scan positive. |

| Other Primary Bone Tumors (Benign/Malignant) | Variable appearances (e.g., giant cell tumor - lytic; chondrosarcoma - lytic with calcification; Ewing sarcoma - permeative/moth-eaten). | Presentation varies (pain, mass, fracture). Imaging characteristics help narrow differential. Biopsy essential for definitive diagnosis. |

References

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2020. Chapter 26: Bones, Joints, and Soft Tissue Tumors.

- Favus MJ, ed. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 8th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. (Sections on Bone Remodeling, Hypercalcemia of Malignancy).

- Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Oct 15;12(20 Pt 2):6243s-6249s.

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone