Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Overview and Pathophysiology

- Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA) in SLE

- Antibodies to Double-Stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA)

- Antibodies to Single-Stranded DNA (anti-ssDNA)

- Anti-Histone Antibodies

- Anti-Nucleosome Antibodies

- Anti-Smith (Anti-Sm) Antibodies

- Anti-Ribosomal P Protein Antibodies

- Differential Diagnosis of SLE

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Overview and Pathophysiology

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease belonging to the group of systemic connective tissue diseases [1]. Its exact etiology (cause) is unknown, but it involves genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and hormonal influences [1, 2]. SLE is characterized by a loss of immune tolerance, leading to the overproduction (hyperproduction) of a wide spectrum of autoantibodies, particularly those directed against components of the cell nucleus (antinuclear antibodies - ANA) [1, 2].

These autoantibodies form immune complexes with their target antigens. These complexes circulate and deposit in various tissues and organs, including small blood vessel walls and kidney glomeruli [1, 2]. Deposition activates the complement system and triggers inflammation, leading to tissue damage [1]. This systemic inflammation can affect multiple organ systems [1, 2].

SLE manifests in various forms [1]:

- Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (CLE): Primarily affects the skin (e.g., discoid lupus), often with a benign course and favorable prognosis.

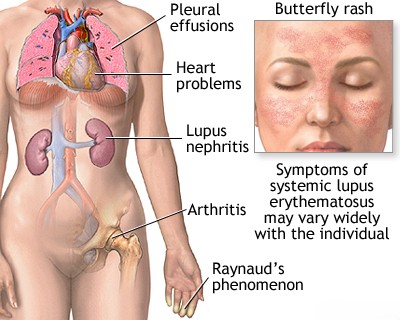

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Involves widespread inflammation affecting connective tissues, blood vessels, and potentially any internal organ system (e.g., kidneys [lupus nephritis], brain [neuropsychiatric lupus], heart, lungs, joints, blood cells). The course can range from mild to life-threatening.

The deposition of autoantibodies and immune complexes, particularly those targeting nucleic acids (like DNA) and associated proteins (like histones), is central to the widespread inflammation and organ damage seen in SLE, especially affecting kidneys and potentially the brain [1, 2].

Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA)

Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA) represent a large, heterogeneous group of autoantibodies that react with various components within the cell nucleus [1, 2]. More than 100 specific ANA targets have been described, including nucleic acids (DNA, RNA), histones, nuclear membrane proteins, components of the spliceosome (involved in mRNA processing), ribonucleoproteins, nucleolar structures, and centromere proteins [1]. Some ANA tests also detect antibodies against cytoplasmic structures [1].

Nuclear antigens targeted by ANA can be grouped [1]:

- True Nuclear Antigens: Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), histones, nuclear RNA.

- Extractable Nuclear Antigens (ENA): A group of proteins/RNA complexes extractable from the nucleus, including Smith (Sm), nuclear Ribonucleoprotein (n-RNP or U1-RNP), Scl-70 (topoisomerase I), SS-A (Ro), SS-B (La), Jo-1 (histidyl tRNA synthetase), and others.

- Cytoplasmic Antigens: Although technically not *nuclear*, antibodies against cytoplasmic targets like SS-A (Ro) - which can be cytoplasmic or nuclear, SS-B (La), and Jo-1 are often included in ANA/ENA testing panels because of their clinical relevance in systemic autoimmune diseases.

Screening tests for ANA often use techniques like indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) on HEp-2 cells or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) using mixtures of common antigens [1, 2]. A positive screening ANA test indicates the presence of one or more autoantibodies reacting with nuclear components but is not specific for SLE [1, 2]. ANA can be positive in many other autoimmune diseases, some infections, certain cancers, and even in healthy individuals (especially at low titers) [1].

Therefore, in patients with a positive ANA screen and clinical suspicion of SLE or another autoimmune disease, confirmatory testing for specific autoantibodies against individual nuclear and cytoplasmic antigens (like anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm, anti-RNP, anti-SSA/SSB, etc.) is recommended to aid in diagnosis and classification [1, 2].

Antibodies to Double-Stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA)

Antibodies targeting native, double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) are considered a highly specific marker for SLE [1, 2]. While present in only about 60-80% of SLE patients, their presence strongly supports the diagnosis [1]. Anti-dsDNA levels often correlate with disease activity, particularly with lupus nephritis (kidney involvement) [1, 2]. Titers frequently rise during disease flares and decrease with effective treatment, making them useful for monitoring disease activity and response to therapy [1, 2]. The presence of IgG-containing circulating immune complexes (CIC) often correlates with anti-dsDNA antibody levels in SLE [1].

Antibodies to Single-Stranded DNA (anti-ssDNA)

Antibodies to single-stranded (denatured) DNA (anti-ssDNA) are less specific for SLE than anti-dsDNA antibodies [1]. They are found in approximately 70% or more of SLE patients but can also occur in various other connective tissue diseases (like RA, Sjögren's, scleroderma), drug-induced lupus, chronic infections (like hepatitis, mononucleosis), and some leukemias [1]. While less specific for diagnosis, IgM class anti-ssDNA antibodies might be more common in discoid lupus erythematosus [1].

Anti-Histone Antibodies

Histones are basic proteins that package DNA within the cell nucleus [1]. Antibodies against histones are found in about 50-70% of patients with idiopathic SLE [1, 2]. However, they are particularly characteristic of drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE), being present in over 95% of cases caused by certain medications like procainamide and hydralazine [1, 2]. Anti-histone antibodies can also be detected less frequently in other conditions like primary biliary cirrhosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma [1]. In idiopathic SLE, their presence does not strongly correlate with specific clinical features [1].

Anti-Nucleosome Antibodies

Nucleosomes are the fundamental repeating units of chromatin, consisting of DNA wrapped around histone proteins [1]. Antibodies to nucleosomes are found in a high percentage (up to 85% or more) of patients with SLE and may appear earlier in the disease course than anti-dsDNA antibodies [1, 2]. While highly associated with SLE, they are not entirely specific and can occasionally be seen in scleroderma and mixed connective tissue disease [1]. Their presence is strongly linked to disease activity, particularly lupus nephritis [2].

Anti-Smith (Anti-Sm) Antibodies

The Smith (Sm) antigen is part of a complex of proteins (small nuclear ribonucleoproteins or snRNPs) involved in mRNA splicing within the spliceosome [1, 2]. Antibodies to the Sm component (Anti-Sm) are found in only about 20-30% of SLE patients, but they are considered highly specific for the disease and are included in the classification criteria [1, 2]. Unlike anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm antibody levels generally do not fluctuate significantly with disease activity or treatment [1]. Some studies suggest an association between anti-Sm antibodies and certain clinical features like lupus psychosis or a lower risk of severe nephritis, but these associations are not consistent across all populations [1].

Anti-Ribosomal P Protein Antibodies

These antibodies target specific phosphoproteins (P0, P1, P2) associated with the ribosome [1, 2]. Antibodies to ribosomal P protein (Anti-Rib P) are found almost exclusively in patients with SLE (present in about 10-20%) [1, 2]. Their presence has been strongly associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations of SLE, particularly lupus psychosis, although they can also be seen in patients without CNS involvement [1, 2].

Differential Diagnosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Antibody Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | Multisystemic: Rash (malar, discoid), photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis (non-erosive), serositis, renal (nephritis), neurological, hematologic (cytopenias). | ANA often high titer, speckled/homogeneous pattern. Anti-dsDNA & Anti-Sm highly specific. Anti-Ro, Anti-La, Anti-RNP, Anti-histone possible. Low complement (C3/C4) common in active disease. |

| Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus (DILE) | Exposure to causative drug (e.g., procainamide, hydralazine, TNF inhibitors). Symptoms often milder (arthralgia, myalgia, serositis, rash). Renal/CNS involvement rare. Resolves on drug withdrawal. | ANA positive (often homogeneous). Anti-Histone positive (>95%). Anti-dsDNA usually negative. Complement normal. |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | Symmetric polyarthritis, primarily small joints (hands, wrists, feet). Morning stiffness >1 hr. Erosive changes on X-ray. Extra-articular features possible (nodules, vasculitis). | RF positive (~70-80%). Anti-CCP highly specific (~70-80%). ANA positive in ~30-50% but non-specific. |

| Sjögren's Syndrome | Dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca), dry mouth (xerostomia). Can have fatigue, arthralgia, extraglandular features (lung, kidney, nerve). Often associated with RA or SLE (secondary). | Anti-SSA (Ro) and/or Anti-SSB (La) positive (high %). RF positive (~70%). ANA positive (~80+%). Schirmer test, salivary gland biopsy helpful. |

| Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma) | Skin thickening/hardening (sclerodactyly, progressing proximally). Raynaud's phenomenon universal. Internal organ involvement common (GI tract, lungs, heart, kidneys). | ANA positive (>90%, often nucleolar/centromere pattern). Anti-Scl-70 (diffuse), Anti-centromere (limited), Anti-RNA polymerase III specific subtypes. RF may be positive. |

| Mixed Connective Tissue Disease (MCTD) | Overlapping features of SLE, scleroderma, and polymyositis (Raynaud's, swollen hands, arthritis, myositis, esophageal dysmotility). | High titer Anti-U1-RNP antibodies (hallmark). ANA positive (speckled). RF may be positive. Other specific antibodies usually absent. |

| Undifferentiated Connective Tissue Disease (UCTD) | Signs/symptoms suggestive of systemic autoimmune disease but do not meet criteria for a specific diagnosis. May evolve over time. | ANA often positive. Other specific antibodies usually negative or low titer. |

| Chronic Infections (e.g., Viral Hepatitis, HIV, Endocarditis) | Can cause arthralgia, fatigue, rash, cytopenias, sometimes low-titer autoantibodies (ANA, RF). | Specific infectious serologies/cultures positive. Autoantibodies non-specific or low titer. |

| Fibromyalgia | Widespread pain, fatigue, sleep issues. Multiple tender points. No objective signs of inflammation or organ damage. | Labs (ANA, ESR/CRP) typically normal. Diagnosis clinical. |

References

- Wallace DJ, Hahn BH, eds. Dubois' Lupus Erythematosus and Related Syndromes. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR. Kelley & Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2017. Chapter on SLE and Antinuclear Antibodies.

- Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982 Nov;25(11):1271-7. (Historical reference for criteria, newer criteria exist - Aringer et al. 2019 EULAR/ACR).

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone