Achilles tendon injury and inflammation

- Achilles Tendon Anatomy & Overview

- Achilles Tendon Pain & Inflammation (Achillodynia, Paratenonitis, Retrocalcaneal Bursitis)

- Achilles Tendon Pain & Inflammation Treatment

- Achilles Tendon Injury (Rupture, Tear/Sprain)

- Achilles Tendon Injury (Rupture, Tear/Sprain) Treatment

- Differential Diagnosis of Achilles/Heel Pain

Achilles Tendon Anatomy & Overview

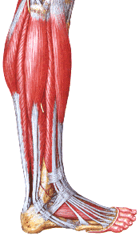

The Achilles tendon (also known as the calcaneal tendon) is the large, cord-like structure connecting the calf muscles to the heel bone (calcaneus) [1]. It is the thickest and strongest tendon in the human body, designed to withstand significant forces during walking, running, and jumping [1].

It is primarily formed by the merging of the tendons from the two main calf muscles: the gastrocnemius (superficial, two-headed muscle) and the soleus (deeper muscle) [1]. Sometimes, the tendon of the small plantaris muscle also contributes [1]. The Achilles tendon inserts onto the posterior (back) surface of the calcaneal tuberosity [1].

Proximally (higher up), the tendon is wide and relatively flat. As it descends towards the heel, it typically narrows and becomes thicker, reaching its narrowest point about 3.5-4 cm above its insertion, before widening again slightly at the attachment site [1]. This narrower region is a common site for injuries due to relatively poorer blood supply [1, 2].

Near the insertion point, between the tendon and the calcaneus, lies the retrocalcaneal bursa, a fluid-filled sac that reduces friction [1]. Another bursa, the subcutaneous calcaneal bursa, lies between the tendon and the skin [1]. The specific twisting arrangement of fibers within the tendon (fibers from the medial gastrocnemius head tend to rotate laterally as they descend) may also influence stress distribution [1].

The robust nature of the human calcaneus and Achilles tendon reflects their crucial role in bipedal locomotion, transmitting the powerful forces generated by the calf muscles to lift the body weight during walking and running (plantarflexion) [1].

Achilles Tendon Pain & Inflammation (Achillodynia, Paratenonitis, Retrocalcaneal Bursitis)

Pain around the Achilles tendon, often broadly termed Achillodynia, can arise from several conditions affecting the tendon itself or surrounding structures [1, 2]:

- Achilles Tendinopathy: This is a general term for painful conditions arising from the tendon itself, usually due to overuse and subsequent degeneration (tendinosis) rather than acute inflammation (tendonitis) [2]. It can affect the main body of the tendon (mid-portion tendinopathy, 2-6 cm above insertion) or the insertion point onto the calcaneus (insertional tendinopathy) [2].

- Paratenonitis: Inflammation of the paratenon, the sheath surrounding the Achilles tendon [1, 2]. This often presents with crepitus (a crackling sensation) during movement [1].

- Retrocalcaneal Bursitis: Inflammation of the bursa located between the Achilles tendon and the calcaneus [1, 2] (also called Morbus Alberti or Haglund's syndrome when associated with a bony prominence on the calcaneus) [1].

- Subcutaneous Calcaneal Bursitis: Inflammation of the bursa between the tendon and the skin, often caused by friction from footwear ("pump bump") [1].

Causes of these conditions are often multifactorial, including [1, 2]:

- Overuse: Sudden increase in activity level, intensity, or duration (common in runners).

- Improper Footwear: Shoes providing poor support or rubbing against the heel.

- Biomechanical Factors: Tight calf muscles, foot misalignment (e.g., excessive pronation).

- Trauma: Direct blow or repetitive minor irritation.

- Systemic Conditions: Inflammatory arthropathies (like rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies), infections (historically, gonorrhea was a recognized cause of bursitis), or metabolic conditions.

Symptoms typically include pain and stiffness around the back of the heel, especially worse in the morning or after periods of inactivity, and aggravated by exercise [1, 2]. Swelling or thickening of the tendon or surrounding area may be present [1]. Pain with dorsiflexion (pulling the foot upwards) is common, particularly with retrocalcaneal bursitis as the tendon compresses the inflamed bursa [1].

Differential diagnosis is important, distinguishing these conditions from Achilles tendon tears/ruptures, calcaneal stress fractures, or avulsion fractures (where the tendon pulls off a piece of bone, sometimes seen in athletes or adolescents - Sever's disease involves the growth plate) [1].

Achilles Tendon Pain & Inflammation Treatment

Treatment for Achillodynia (tendinopathy, paratenonitis, bursitis) is primarily conservative initially and focuses on reducing pain and inflammation, and addressing underlying causes [1, 2]:

- Rest & Activity Modification: Avoiding activities that aggravate the pain is crucial.

- Ice Application: Applying ice packs can help reduce pain and inflammation.

- Footwear Modification: Wearing supportive shoes, potentially with a heel lift to reduce tension on the tendon. Avoiding shoes that rub the affected area.

- Stretching & Strengthening: Gentle stretching exercises for the calf muscles and eccentric strengthening exercises (controlled lengthening of the muscle/tendon unit) are often key components of rehabilitation, particularly for tendinopathy.

- Medications: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may provide temporary pain relief, but their long-term benefit for tendinopathy is debated.

- Physical Therapy: Can guide appropriate exercises, provide manual therapy (massage, mobilization), and utilize modalities like ultrasound or iontophoresis.

- Orthotics: Custom or over-the-counter arch supports may help correct biomechanical issues.

- Injections: Corticosteroid injections directly into the tendon are generally avoided due to the risk of tendon rupture. Injections into the retrocalcaneal bursa may be considered for persistent bursitis, but carry some risk.

- Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy (ESWT): Can be effective for chronic tendinopathy.

- Nitroglycerin Patches: Sometimes used off-label to improve blood flow and healing.

If conservative measures fail after several months (typically 3-6 months), surgical options may be considered [1, 2]:

- For Tendinopathy: Surgical debridement (removing damaged tissue), potentially with tendon repair or transfer if significant degeneration exists.

- For Retrocalcaneal Bursitis/Haglund's Deformity: Surgical excision (removal) of the inflamed bursa and resection (shaving down) of the bony prominence on the calcaneus.

Full recovery after surgery can take several months [1].

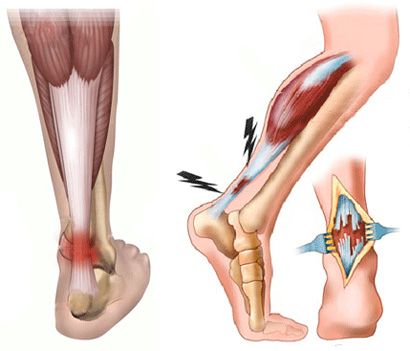

Achilles Tendon Injury (Rupture, Tear/Sprain)

Acute injuries to the Achilles tendon range from mild strains (sprains) involving microscopic fiber damage to partial tears or complete ruptures [1, 2].

Achilles Tendon Rupture: This typically occurs in middle-aged individuals (30-50 years), often during recreational sports ("weekend warriors") [2]. The rupture usually happens in the area of reduced blood supply, about 2-6 cm above the calcaneal insertion [1, 2].

Causes [1, 2]:

- Indirect Trauma (Most Common): Sudden, forceful plantarflexion against resistance (pushing off) or violent dorsiflexion of a plantarflexed foot (e.g., landing awkwardly from a jump, stumbling into a hole).

- Direct Trauma: A direct blow or laceration to the tendon.

- Underlying Tendinopathy: Pre-existing degeneration can weaken the tendon, making it more susceptible to rupture.

- Medications: Fluoroquinolone antibiotics and long-term corticosteroid use can increase rupture risk.

Symptoms of Rupture [1, 2]:

- Sudden, sharp pain in the back of the ankle, often described as feeling like being kicked or shot.

- An audible "pop" or snapping sensation at the time of injury.

- Difficulty walking, especially pushing off the toes (weak or absent plantarflexion).

- Swelling and bruising around the ankle and heel.

- A palpable defect or gap in the tendon may be felt a few centimeters above the heel bone.

- Positive Thompson Test: When the patient lies prone with feet hanging off the table, squeezing the calf muscle should normally cause passive plantarflexion of the foot. Absence of this movement suggests a complete rupture.

Diagnosis: Often clinical based on history and physical exam (Thompson test, palpable gap) [1, 2]. Ultrasound or MRI can confirm the diagnosis, assess the extent of the tear (partial vs. complete), and evaluate tendon quality, especially if the diagnosis is unclear or surgery is planned [1, 3].

Standard X-rays are usually normal in cases of pure tendon rupture but can help rule out associated bony injuries like calcaneal fractures [1].

Achilles Tendon Injury (Rupture, Tear/Sprain) Treatment

Treatment options for Achilles tendon ruptures include surgical repair and non-surgical (conservative) management [1, 2, 4].

- Surgical Repair: This involves stitching the torn ends of the tendon back together [1, 2, 4].

- Open Repair: A traditional incision is made over the tendon to directly visualize and suture the ends.

- Percutaneous/Minimally Invasive Repair: Smaller incisions are used with specialized instruments to pass sutures across the tear. This may reduce wound complications but carries a slightly higher risk of nerve injury (sural nerve).

- Non-Surgical (Conservative) Management: This involves immobilizing the foot and ankle in a cast or boot, typically with the foot initially in plantarflexion (to bring the tendon ends closer) and gradually progressing towards a neutral position over several weeks (e.g., 6-12 weeks total immobilization) [1, 4]. This avoids surgical risks but may have a slightly higher re-rupture rate and potentially less strength compared to surgical repair [4]. It is a viable option, particularly for less active individuals, those with medical comorbidities increasing surgical risk, or those who present acutely [4].

Regardless of the initial treatment (surgical or non-surgical), a prolonged period of rehabilitation is required, involving gradual progression of weight-bearing, range-of-motion exercises, and strengthening [1, 4]. Full recovery and return to sports can take 6-12 months [1].

Partial tears or strains (sprains) are usually treated conservatively with rest, ice, immobilization (boot or brace), and progressive rehabilitation similar to tendinopathy treatment [1].

Differential Diagnosis of Achilles/Heel Pain

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Achilles Tendon Rupture (Complete) | Sudden sharp pain ("kick" sensation), audible "pop", inability to stand on toes, palpable gap in tendon, positive Thompson test. Often middle-aged recreational athlete. | Clinical diagnosis often clear. Ultrasound or MRI confirms complete tear and gap size. X-ray rules out fracture. |

| Achilles Tendinopathy (Mid-portion or Insertional) | Gradual onset pain and stiffness, worse with activity/morning. Tendon thickening/nodule palpable 2-6 cm above insertion (mid-portion) or pain directly at insertion. Thompson test negative. | Clinical diagnosis. Ultrasound or MRI shows tendon thickening, degeneration (tendinosis), +/- partial tears, calcification (insertional). |

| Achilles Paratenonitis | Pain, swelling, tenderness surrounding the tendon (not just the tendon itself). Often palpable or audible crepitus with ankle movement. | Clinical diagnosis. Ultrasound may show fluid/thickening around the tendon sheath (paratenon). MRI can also confirm. Tendon itself may be normal. |

| Retrocalcaneal Bursitis | Pain localized deep between the Achilles tendon and the calcaneus. Tenderness anterior to the tendon insertion. Pain often worse with dorsiflexion. May be associated with Haglund's deformity (bony bump). | Clinical diagnosis. Ultrasound or MRI shows inflamed/fluid-filled retrocalcaneal bursa. X-ray may show Haglund's deformity. |

| Subcutaneous Calcaneal Bursitis ("Pump Bump") | Pain, redness, swelling superficial to the Achilles insertion, often irritated by shoe wear. | Clinical diagnosis. Imaging usually not needed unless ruling out other pathology. |

| Sever's Disease (Calcaneal Apophysitis) | Heel pain in active children/adolescents (typically 8-14 yrs). Pain localized to the posterior calcaneus growth plate, aggravated by activity. | Clinical diagnosis based on age, location of tenderness. X-rays may show fragmentation/sclerosis of the apophysis but can be normal. |

| Plantar Fasciitis | Pain typically on the *underside* of the heel, worse with first steps in the morning or after rest. Achilles area usually not tender. | Clinical diagnosis. Imaging usually not needed initially. Ultrasound/MRI can show thickened fascia. |

| Calcaneal Stress Fracture | Gradual onset heel pain, worse with weight-bearing activity. Tenderness directly over calcaneus bone (positive squeeze test). | X-rays often initially normal. Bone scan or MRI confirms stress fracture. |

| Sural Nerve Entrapment/Irritation | Burning pain, numbness, tingling along the lateral aspect of the ankle/foot. May have positive Tinel's sign over nerve pathway. | Clinical diagnosis. Nerve conduction studies may help. Ultrasound/MRI might show nerve course/irritation source. |

| Systemic Inflammatory Arthritis (e.g., Spondyloarthropathy) | Can cause enthesitis (inflammation at tendon/ligament insertion) at Achilles insertion. Often bilateral or associated with other joint/systemic symptoms. | Clinical picture. Inflammatory markers (ESR/CRP) may be high. HLA-B27 testing. Imaging shows enthesitis/erosions. |

References

- Maffulli N, Longo UG. How I manage chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2008 Dec;42(12):959-61. (Or similar review on tendinopathy/bursitis).

- Skinner HB, McMahon PJ. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics. 5th ed. McGraw Hill; 2014. Chapter 9: Foot & Ankle Trauma & Chapter 14: Foot & Ankle Reconstruction (Sections on Achilles disorders).

- Hess GW. Achilles tendon rupture: a review of etiology, population, diagnosis, and treatment. Foot Ankle Spec. 2010 Apr;3(2):70-3.

- Soroceanu A, Sidhwa F, Aarabi S, Kaufman A, Glazebrook M. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012 Dec 5;94(23):2136-43.

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone