Joint ankylosis

Joint Ankylosis Overview

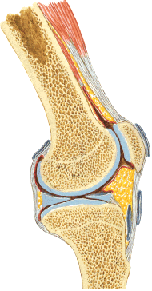

Ankylosis refers to the stiffness or immobility of a joint due to abnormal adhesion and rigidity of the bones of the joint, which may be the result of injury or disease [1]. The rigidity may be complete or partial and may be due to inflammation of the articular cartilage (true ankylosis) or surrounding tissues (false ankylosis) [1].

It develops as a consequence of pathological changes within the joint, often stemming from trauma (especially severe intra-articular fractures), inflammatory arthritis (like rheumatoid arthritis or septic arthritis), or degenerative joint disease (osteoarthritis) [1, 2]. This process leads to progressive stiffness and eventual complete loss of motion in the affected joint.

Ankylosis is classified based on the type of tissue bridging the joint space [1]:

- Fibrous Ankylosis: The joint space is filled with fibrous connective tissue, allowing minimal, often painful, residual movement.

- Bony (Osseous) Ankylosis: The joint surfaces fuse together with bone, resulting in complete immobility and often less pain than fibrous ankylosis.

Joint Ankylosis Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

The primary symptom of ankylosis is the loss of motion or significant stiffness in the affected joint [1]. The degree of functional impairment depends heavily on the position in which the joint becomes fixed [1].

For example, if the knee joint becomes ankylosed (fused) in a significantly bent position, normal walking becomes extremely difficult or impossible. However, if the knee fuses in a straight or slightly bent position, the patient might still be able to walk and perform many activities, albeit with an altered gait [1].

Causes [1, 2]:

- Inflammatory joint diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, septic arthritis, advanced osteoarthritis).

- Severe intra-articular trauma, especially fractures that disrupt the joint surface congruity.

- Open joint injuries complicated by chronic infection (suppurative arthritis), leading to cartilage destruction and replacement by fibrous or bony tissue.

- Prolonged immobilization of a joint (e.g., in a cast) can sometimes contribute to stiffness and fibrous ankylosis, although true bony ankylosis from immobilization alone is less common unless there's underlying joint damage.

Differentiating Symptoms [1]:

- Fibrous Ankylosis: Patients often complain of pain, especially with attempted movement or weight-bearing. Some minimal, "rocking" or "springy" residual motion may be present.

- Bony Ankylosis: Pain is typically absent once fusion is complete. There is a complete lack of movement at the joint.

Joint Ankylosis Diagnosis

The diagnosis of joint ankylosis typically begins with a consultation with an orthopedic surgeon or rheumatologist [1]. The process involves [1, 3]:

- Medical History: Discussing the onset of symptoms, previous injuries, history of arthritis or infections, and the degree of functional limitation.

- Physical Examination: Assessing the range of motion (or lack thereof) in the affected joint, evaluating the position of fixation, checking for pain, swelling, or deformity, and assessing the function of surrounding muscles.

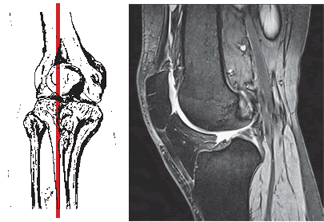

- Imaging Studies:

- X-rays: Usually the initial imaging study. Can show narrowing or complete obliteration of the joint space, bone bridging across the joint (bony ankylosis), and the position of fusion.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides more detailed bony anatomy, useful for assessing the extent of bony fusion and planning potential surgery.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Less commonly used for established bony ankylosis but can be helpful in evaluating fibrous ankylosis, assessing surrounding soft tissues, and identifying underlying inflammatory processes.

- Pneumoarthrography/Arthrography: Older techniques involving injecting air or contrast into the joint, largely replaced by CT and MRI.

Based on the evaluation, the type (fibrous or bony) and cause of ankylosis are determined, guiding the treatment plan [1].

Joint Ankylosis Treatment

Treatment for joint ankylosis aims to relieve pain and improve function, considering the type of ankylosis, the joint involved, the position of fixation, and the patient's overall health and activity level [1, 2]. Options range from conservative measures to surgery [1].

Conservative Treatment: More effective for preventing ankylosis or managing symptoms of fibrous ankylosis. Less effective for established bony ankylosis [1].

- Prevention: Early and appropriate treatment of joint injuries (fractures, dislocations) and inflammatory conditions (arthritis, infections) is key [1, 2]. Early mobilization and physical therapy after injury or surgery help maintain joint motion [1]. For patients requiring prolonged immobilization (e.g., in a cast), isometric muscle exercises (tensing muscles without moving the joint) can help maintain muscle tone [1].

- Pain Management: For painful fibrous ankylosis [1]:

- Medications: NSAIDs, analgesics.

- Therapeutic Injections: Corticosteroid injections into the joint space or surrounding tissues may provide temporary relief.

- Physical Therapy & Rehabilitation [1]:

- Physical Therapy Modalities: Heat, ultrasound (UHF), electrophoresis, electrical stimulation (SMT) may help manage pain and inflammation associated with fibrous ankylosis or post-operatively.

- Manual Therapy: Gentle mobilization techniques might provide minimal improvement in fibrous ankylosis but are ineffective for bony ankylosis.

- Massage: Can help manage surrounding muscle tightness and pain.

- Therapeutic Exercise (Gymnastics): Focuses on maintaining strength and flexibility in surrounding joints and muscles. Stretching may provide limited benefit in early fibrous ankylosis.

Operative (Surgical) Treatment: Often necessary for significant functional impairment, especially if the joint is fused in a non-functional position, or for painful fibrous ankylosis unresponsive to conservative measures [1, 2].

- Arthroplasty (Joint Replacement): Replacing the damaged joint surfaces with artificial components (prosthesis) [1, 2]. This is the most common surgical solution for restoring motion and relieving pain in joints like the hip and knee affected by ankylosis secondary to arthritis or trauma [2].

- Resection Arthroplasty: Removing bone from the joint surfaces to create a gap, allowing motion but potentially leading to instability [1]. Less commonly performed now.

- Arthrodesis (Joint Fusion): Surgically fusing the joint permanently in a functional position [1, 2]. This eliminates pain from the joint but sacrifices all motion [1]. It may be considered for joints where replacement is not feasible or has failed, or in specific joints like the wrist or ankle where stability is paramount [1, 2].

- Osteotomy: Cutting and realigning the bone near the joint to correct deformity, sometimes performed in conjunction with other procedures [1].

The choice of surgical procedure depends on the specific joint, the cause and type of ankylosis, the patient's age, activity level, and overall health [1, 2].

Differential Diagnosis of Joint Stiffness/Immobility

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ankylosis (Fibrous or Bony) | Complete or near-complete loss of joint motion. History of significant trauma, severe arthritis, or infection. Fibrous: minimal painful motion possible. Bony: complete rigidity, often painless. | X-ray shows joint space obliteration, bone bridging across joint (bony). CT confirms fusion. MRI evaluates fibrous tissue. |

| Arthrofibrosis / Joint Contracture | Stiffness and significant loss of motion, but not complete fusion. Often follows surgery, trauma, or prolonged immobilization. Due to capsular thickening/adhesions or muscle contracture. | X-ray shows intact joint space (though may be narrowed). Clinical exam demonstrates limited passive range of motion. MRI may show capsular thickening/scarring. |

| Severe Osteoarthritis | Gradual onset pain and stiffness, worse with activity, improves with rest. Crepitus, reduced range of motion, bony enlargement. Joint space still present but narrowed. | X-ray shows joint space narrowing, osteophytes (bone spurs), subchondral sclerosis/cysts. |

| Inflammatory Arthritis (e.g., RA, Spondyloarthritis - Active) | Joint pain, stiffness (often worse in morning), swelling, warmth. May have systemic symptoms. Range of motion limited by pain/inflammation/effusion. Eventually leads to joint damage/ankylosis if uncontrolled. | Clinical presentation. Elevated inflammatory markers (ESR/CRP). Specific autoantibodies (RF, anti-CCP, HLA-B27). X-ray/MRI show joint effusion, erosions, inflammation, later joint destruction. |

| Locked Joint (Mechanical Block) | Sudden inability to fully extend or flex the joint. Often due to displaced meniscus tear (bucket-handle) or loose body (cartilage/bone fragment) within the joint. May have history of clicking/catching. | Clinical history and exam suggestive. X-ray may show loose body. MRI confirms meniscus tear or loose body. |

| Heterotopic Ossification | Abnormal bone formation in soft tissues around a joint, often after trauma, surgery, or neurological injury. Causes progressive stiffness and loss of motion. | X-ray shows mature bone formation outside the joint capsule. CT/Bone scan can detect earlier stages. |

| Muscle Spasm / Guarding | Severe pain leads to involuntary muscle contraction, limiting passive and active motion. Underlying joint structure is normal. Resolves with pain relief/anesthesia. | Clinical exam findings. Imaging normal. |

References

- Canale ST, Beaty JH. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2017. Chapter 3: Arthrodesis & Chapter 8: Principles of Arthroplasty. (Covers surgical options for end-stage joint disease/ankylosis).

- Skinner HB, McMahon PJ. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics. 5th ed. McGraw Hill; 2014. Chapter 2: Arthritis & Related Conditions & Chapter on specific joint trauma.

- Resnick D, Kransdorf MJ. Bone and Joint Imaging. 3rd ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2005. Chapters on specific joints and disease processes (e.g., arthritis, trauma sequelae).

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone