Hip dislocation

Hip dislocation Overview

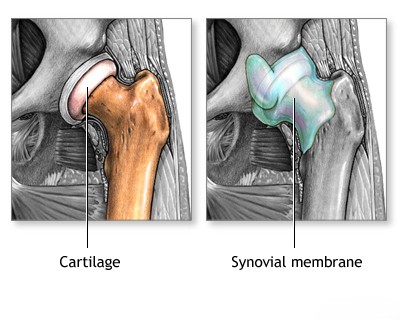

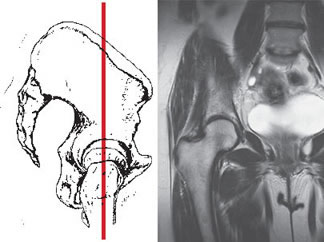

Hip dislocations account for a significant portion of major joint dislocations [1]. They occur when the head of the femur (thigh bone) is forced out of its socket, the acetabulum, in the pelvis [1, 2]. Depending on whether the femoral head is displaced forward (anteriorly) or backward (posteriorly) relative to the acetabulum, hip dislocations are classified as anterior or posterior [1].

Further classification depends on the precise final position of the displaced femoral head (e.g., superior/inferior, or specific anatomical locations like obturator, iliac, pubic) [1].

Mechanisms of hip dislocation often involve significant force, such as [1]:

- Flexion and adduction (most common mechanism for posterior dislocations, e.g., dashboard injury)

- Extension and external rotation (often associated with anterior dislocations)

- Flexion and abduction (less common mechanism)

Instrumental diagnostic methods for confirming hip dislocation and assessing associated injuries may include [1, 4]:

- X-rays of the hip and pelvis (Standard initial imaging)

- Computed tomography (CT) scan of the hip joint (Excellent for detecting associated fractures of the femoral head or acetabulum)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hip joint (Best for evaluating soft tissue damage like labral tears, ligament injuries, and assessing the risk of avascular necrosis)

Posterior hip dislocation

Posterior dislocations are the most common type, accounting for approximately 80-90% of all hip dislocations [1, 2]. The typical mechanism involves significant force applied to a flexed knee with the hip also flexed and adducted (e.g., a 'dashboard injury' in a motor vehicle accident) [1]. This force drives the femoral head posteriorly out of the acetabulum, often tearing the posterior joint capsule and associated ligaments (like the ischiofemoral ligament) [1]. The exact position of the dislocated head (e.g., iliac - superiorly, or ischial - inferiorly) depends on the degree of hip flexion and rotation at the time of impact [1].

Posterior hip dislocation symptoms

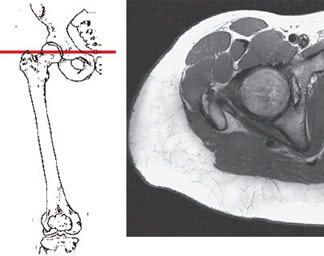

Symptoms of a posterior hip dislocation typically include severe pain and inability to move the affected leg [1]. The limb is classically held in a characteristic position: flexed at the hip, adducted (drawn towards the midline), and internally rotated [1]. The leg often appears shortened compared to the uninjured side [1]. Attempts at passive movement, especially abduction and external rotation, meet with palpable resistance ('springy block') [1].

The greater trochanter may be palpable more posteriorly than usual and positioned superior to the Roser-Nélaton line (an imaginary line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the ischial tuberosity) [1]. In thin individuals, the displaced femoral head may sometimes be palpable in the gluteal region [1].

Sciatic nerve injury (ranging from temporary neuropraxia to more severe damage) can occur in up to 20% of posterior hip dislocations [1, 5]. This results from stretching or compression of the nerve by the displaced femoral head and can lead to symptoms like foot drop (inability to lift the front of the foot) or sensory changes in the leg and foot [1, 5].

Anterior hip dislocation

Anterior hip dislocations are less common than posterior ones [1]. They typically result from forceful abduction (moving the leg away from the body), often combined with extension and external rotation of the hip (e.g., a fall that forces the leg outward and backward) [1]. The femoral head tears through the anterior capsule and comes to rest anteriorly, often classified by its location: inferior (obturator type, near the obturator foramen) or superior (pubic or iliac type, near the pubic bone or iliac wing) [1].

Neurovascular structures located anteriorly, particularly the femoral nerve, artery, and vein, are at risk of compression or direct injury by the displaced femoral head in anterior dislocations [1].

Anterior hip dislocation symptoms

Symptoms of an anterior hip dislocation include severe pain and inability to move the affected leg [1]. The characteristic position depends on the subtype: superior (pubic/iliac) dislocations often present with the hip in extension, slight abduction, and external rotation [1]. Inferior (obturator) dislocations typically present with marked flexion, abduction, and external rotation [1]. The limb may appear longer than the unaffected side [1]. Active movement is impossible due to pain and the mechanical block [1].

The displaced femoral head may be palpable anteriorly, often in the groin region near the inguinal ligament [1]. The femoral artery pulse, normally felt just inferior to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament, may be difficult to palpate or feel displaced by the femoral head [1]. The femoral nerve (N. femoralis) is vulnerable to compression, potentially causing weakness in the quadriceps muscle or numbness over the anterior thigh [1].

Inferior (obturator) anterior dislocations typically occur with mechanisms involving hyperabduction and flexion, forcing the head through the anteroinferior capsule near the obturator foramen [1]. The position of marked flexion, abduction, and external rotation is highly characteristic [1].

A distinct, though related, injury is a central fracture-dislocation [1]. In this case, the femoral head is driven medially through a fractured acetabulum into the pelvic cavity [1]. This severe injury typically results from a high-energy direct blow to the side of the hip (greater trochanter), such as in a fall from height or a side-impact collision [1]. Hip motion, particularly abduction, is severely restricted and painful [1]. The greater trochanter may appear less prominent laterally [1]. In some instances, the displaced femoral head might be palpable via rectal examination [1]. Pelvic X-rays clearly demonstrate the medial displacement of the femoral head into the pelvis along with the associated acetabular fracture [1].

Hip dislocation reduction and Treatment

Reduction (relocating the femoral head back into the acetabulum) of a hip dislocation is an orthopedic emergency [1, 2]. Prompt reduction, ideally within 6 hours of the injury, is crucial to minimize the risk of avascular necrosis (AVN) – death of bone tissue due to interrupted blood supply – of the femoral head [1, 2].

Closed reduction (without surgery) typically requires adequate pain control and muscle relaxation, often achieved with procedural sedation in the emergency department or under general/spinal anesthesia in the operating room [1, 2]. Older methods involving simple longitudinal traction are often ineffective due to powerful muscle spasms and tension in intact ligaments (like the strong iliofemoral ligament) [1].

Several closed reduction techniques exist [1, 2]:

- Posterior Dislocation Reduction:

- Allis Maneuver: The patient lies supine (on their back). An assistant stabilizes the pelvis. The physician flexes the patient's hip and knee to 90 degrees, applies steady upward traction in line with the femur, and gently internally/externally rotates the hip to guide the femoral head over the acetabular rim and back into the socket. A palpable 'clunk' often signifies successful reduction.

- Stimson Maneuver: The patient is positioned prone (face down) with the affected leg hanging off the edge of the table. Downward traction (potentially with added weights) is applied at the ankle or calf, with gentle rotation, allowing gravity and muscle relaxation to assist reduction. The Janelidze maneuver is similar.

- Anterior Dislocation Reduction: Techniques often involve traction generally in line with the limb's deformed position, followed by gentle adduction and internal rotation (for superior types) or extension (for inferior types) to lever the head back into the socket.

Closed reduction of a hip dislocation, often performed under sedation or anesthesia [2]. Post-reduction imaging (X-ray, possibly CT) is essential to confirm concentric reduction and rule out associated fractures or interposed soft tissue [1, 2].

After successful reduction, confirmed by X-ray, management includes [1, 2]:

- Assessment for Associated Injuries: Careful examination for nerve injuries (especially sciatic) and CT scan if fractures are suspected.

- Stability Assessment: Checking the hip's stability through a gentle range of motion.

- Immobilization/Protected Weight-Bearing: Depending on stability and associated injuries, this may involve a period of bed rest, a hip brace, abduction pillow, or crutches (toe-touch or non-weight bearing), often for several weeks.

- Pain Management: Analgesics (e.g., NSAIDs, opioids initially) are essential for comfort.

- Rehabilitation: Physical therapy is crucial. It begins with gentle range-of-motion exercises once pain allows and progresses to strengthening exercises for the hip and thigh muscles as healing progresses, aiming to restore function and stability.

- Follow-up: Long-term follow-up, potentially including MRI, is necessary to monitor for complications like AVN or post-traumatic arthritis.

- Adjunctive Treatments: Specific treatments like acupuncture might be considered for associated complications like persistent pain or nerve symptoms, but are generally adjunctive to standard care.

Open reduction (surgery) may be necessary if closed reduction fails, if there are associated fractures requiring fixation, or if soft tissue is blocking reduction [1, 2].

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Hip Pain / Immobility After Trauma

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Hip Dislocation (Posterior/Anterior) | High-energy trauma mechanism. Severe pain, inability to bear weight, characteristic limb deformity (e.g., posterior: flexed, adducted, internally rotated, shortened; anterior: abducted, externally rotated). | X-ray confirms femoral head out of acetabulum. CT evaluates for associated fractures (femoral head, acetabulum). MRI assesses soft tissues, AVN risk later. |

| Femoral Neck Fracture | Often lower energy trauma in elderly (fall), high energy in younger. Severe groin/hip pain, inability to bear weight. Leg often shortened and externally rotated (if displaced). | X-ray shows fracture line at femoral neck. MRI/CT may be needed for occult fractures. Femoral head remains in acetabulum. |

| Intertrochanteric Fracture | Trauma (often fall in elderly). Pain often more lateral over greater trochanter. Inability to bear weight. Leg usually shortened and externally rotated. | X-ray shows fracture line between greater and lesser trochanters. Femoral head in acetabulum. |

| Pelvic Ring Fracture / Acetabular Fracture (without central dislocation) | High-energy trauma usually. Severe pain, instability, inability to bear weight. May have associated internal injuries. Hip joint itself may or may not be directly involved. | Pelvic X-rays (AP, inlet, outlet views) and CT scan essential to define fracture pattern. Hip joint may be congruent unless acetabulum fractured. |

| Hip Subluxation | Partial displacement of femoral head from acetabulum. May occur with trauma or underlying instability (e.g., dysplasia). Pain, feeling of instability, clicking. May spontaneously reduce. | Stress X-rays or MRI may show joint incongruity or labral/ligamentous injury. CT can assess bony morphology. |

| Severe Hip Sprain / Soft Tissue Injury | Significant trauma but without dislocation or major fracture. Pain, swelling, limited motion, difficulty weight-bearing. No gross deformity. | X-rays negative for dislocation/fracture. MRI shows soft tissue edema, muscle/ligament tears, effusion. |

References

- Tornetta P III, Mostafavi HR, Riina J, et al. Hip Dislocation: Current Treatment Regimens. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999 Jan-Feb;7(1):1-8. (Or a more recent review article on hip dislocations).

- Skinner HB, McMahon PJ. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics. 5th ed. McGraw Hill; 2014. Chapter 6: Hip & Femur Trauma.

- Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz RW, Heckman JD. Rockwood and Green's Fractures in Adults. 8th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. Volume 2, Chapter 43: Dislocations and Fracture-Dislocations of the Hip.

- Steinberg ME, Hayken GD, Steinberg DR. Avascular Necrosis of the Femoral Head. In: Chapman's Comprehensive Orthopaedic Surgery. 4th ed. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2019. (Discusses imaging for AVN).

- Nerve Injuries Associated with Hip Dislocations. Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics. Available at: [Insert appropriate URL if available, e.g., from Duke Orthopaedics website, but requires checking for a specific citeable section]. Or cite the relevant section in Rockwood/Skinner.

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone