Mandibular (jaw) dislocation

Mandibular (Jaw) Dislocation Overview

Mandibular (jaw) dislocations account for approximately 2.5% of all joint dislocations [1]. They can be unilateral (affecting one side) or bilateral (affecting both sides), with bilateral dislocations being more common [1, 2].

Mandibular dislocations typically occur due to excessive opening of the mouth, such as during yawning, vomiting, dental procedures (like tooth extraction), intubation (insertion of a gastric or endotracheal tube), or less commonly, from a direct downward blow to the chin when the mouth is open [1, 2].

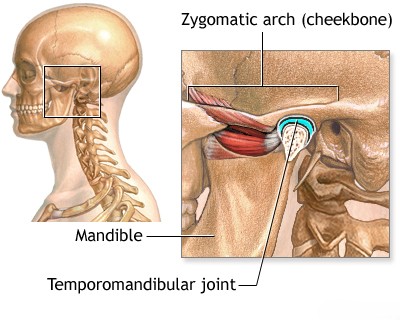

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) connects the mandible (lower jaw) to the temporal bone of the skull [2]. Within the joint, an articular disc (meniscus) divides the joint cavity into upper and lower compartments [2].

During normal mouth opening, the head of the mandible (condyle) rotates and then slides forward along the articular eminence (tuberculum articulare), a bony prominence on the temporal bone just anterior to the joint socket (glenoid fossa) [2]. Usually, this forward movement is limited by ligaments and muscle action [2].

A predisposing factor for dislocation can be a naturally flatter or underdeveloped articular eminence, which provides less of a barrier to forward condylar movement [1]. This anatomical variation is sometimes seen more often in women, potentially contributing to a higher incidence of dislocation in females [1].

The mechanism of dislocation involves the mandibular condyle(s) sliding too far forward, over the peak of the articular eminence, and becoming lodged in the space anterior to it [1, 2]. The tension in the surrounding ligaments (like the stylomandibular and sphenomandibular ligaments) and the spasm of the powerful masticatory (chewing) muscles (particularly the masseter and pterygoids) then pull the jaw upwards and forwards, effectively locking the condyle(s) in the dislocated position and preventing them from sliding back into the fossa [1, 2].

Mandible Bilateral Dislocation Symptoms

The characteristic symptoms of a bilateral mandibular dislocation include [1, 2]:

- Inability to close the mouth (mouth is held open).

- Jaw protruding forward (prognathic appearance) and feeling "locked".

- Inability to bring the teeth together (malocclusion).

- Excessive drooling (salivation) due to difficulty swallowing.

- Difficulty speaking clearly.

- Cheeks may appear flattened or hollowed.

- A palpable depression or pit may be felt just in front of the tragus of the ear (where the condyle normally sits).

- The displaced mandibular condyle(s) may be palpable anteriorly, often under the zygomatic arch (cheekbone).

- Pain and muscle spasm in the jaw area.

In a unilateral dislocation, these symptoms are present primarily on the affected side [1]. The jaw is less rigidly fixed, and the chin typically deviates towards the unaffected (healthy) side [1]. This deviation towards the unaffected side helps distinguish it from a condylar fracture, where the chin usually deviates towards the fractured side due to muscle pull [1].

Mandibular (Jaw) Dislocation Reduction Technique

Reduction (relocation) of an acute mandibular dislocation is often straightforward and can frequently be performed without anesthesia, although local anesthesia or conscious sedation may be beneficial for patient comfort and muscle relaxation [1, 2].

The most common method is the Hippocratic technique [1, 2]:

- The patient sits upright, preferably with head support.

- The clinician stands facing the patient.

- The clinician wraps their thumbs (protected with gauze or tape to prevent accidental biting) and places them on the occlusal (biting) surfaces of the patient's lower molars bilaterally.

- The fingers of both hands curl under the mandible externally for grip and leverage.

- The clinician applies firm, steady downward pressure on the molars with the thumbs, while simultaneously applying upward pressure on the chin with the fingers.

- This downward pressure aims to disengage the condyles from their position anterior to the articular eminence, overcoming muscle spasm.

- Once downward movement is achieved, the jaw is gently guided posteriorly (backward) and then allowed to glide upward into its normal position within the glenoid fossa.

- A palpable 'clunk' often signifies successful reduction as the condyles relocate.

Demonstration of a common technique (similar to the Hippocratic method) for reducing a mandibular dislocation [2]. Note the clinician's thumb placement on the molars and finger placement under the chin for leverage. Protecting the thumbs is crucial.

If bilateral reduction is difficult, reducing one side at a time may be attempted [1]. If manual reduction fails, general anesthesia may be required to achieve adequate muscle relaxation [1].

After successful reduction [1, 2]:

- Confirm reduction by asking the patient to gently close their mouth and checking occlusion.

- Apply a supportive dressing (e.g., Barton bandage or soft cervical collar worn backwards) for a short period (days to 1-2 weeks) to limit wide mouth opening and prevent immediate recurrence.

- Advise the patient to avoid wide yawning, large bites of food, and other activities that stress the TMJ for several weeks. A soft diet is recommended initially.

- Pain relief with NSAIDs may be helpful.

Chronic or recurrent dislocations may occur [1]. Management options range from conservative measures (limiting jaw opening, physiotherapy) to interventions like sclerotherapy (injecting irritating solutions to tighten tissues) or surgical procedures to address anatomical issues or tighten ligaments [1]. Irreducible dislocations, although rare, may require open surgical reduction [1].

Posterior mandibular dislocation is extremely rare and typically results from a direct, forceful blow to the chin while the mouth is closed, driving the condyles backward [1]. This can potentially damage the external auditory canal [1].

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Jaw Locking / Pain

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Mandibular Dislocation (Anterior) | Inability to close mouth, jaw locked open/forward. Often after wide opening (yawn, dental procedure). Palpable preauricular depression, condyle palpable anteriorly. | Clinical diagnosis usually sufficient. X-ray (e.g., panoramic, Towne's view) confirms condyle anterior to articular eminence. CT rarely needed unless fracture suspected. |

| Mandibular Fracture (esp. Condylar) | History of trauma (direct blow). Pain, swelling, malocclusion, difficulty opening *or* closing depending on fracture type/displacement. Chin may deviate towards fractured side. Preauricular pain/tenderness. | X-ray (panoramic, mandibular series) shows fracture line. CT scan provides better detail of condylar/complex fractures. |

| Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Dysfunction / Internal Derangement | Pain (often preauricular), clicking, popping, limited opening ("closed lock" if disc displaced without reduction), or deviation. May have history of bruxism or trauma. Usually less acute/dramatic locking than dislocation. | Clinical exam often reveals clicking/tenderness. X-rays usually normal. MRI is best for evaluating TMJ disc position and integrity. |

| Tetanus / Severe Muscle Spasm (Trismus) | Inability to OPEN the mouth (trismus), not locked open. Generalized muscle rigidity, spasms (e.g., risus sardonicus). History of wound/lack of immunization (for tetanus). | Clinical diagnosis based on characteristic spasms/rigidity. Wound culture may identify C. tetani (often negative). Imaging usually normal. |

| Dental Abscess / Severe Odontogenic Infection | Severe tooth/jaw pain, facial swelling, fever. May cause reactive muscle spasm (trismus - difficulty opening), but not typically locked open dislocation. | Dental exam identifies infected tooth. X-rays/CT may show abscess or osteomyelitis. Elevated inflammatory markers. |

| Peritonsillar Abscess / Deep Neck Space Infection | Sore throat, fever, muffled voice, dysphagia, often significant trismus (difficulty opening). | Clinical exam shows pharyngeal/tonsillar swelling/deviation. CT neck confirms abscess location. |

References

- Laskin DM, Abubaker AO. Diagnosis and Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation. In: Fonseca RJ, ed. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2nd ed. Saunders; 2009. Vol 3, Chapter 35. (Or a similar OMFS textbook chapter).

- Thomsen TW, Benjamin B, Setnik GS. Procedures Consult: Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Dislocation Reduction. Elsevier; 2008. (Or similar Emergency Medicine procedure reference).

- White SC, Pharoah MJ. Oral Radiology: Principles and Interpretation. 7th ed. Mosby; 2014. Chapter 24: Temporomandibular Joint Imaging.

- Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2018. Chapter 41: Maxillofacial Trauma.

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone