Joint contractures

Joint Contractures Overview

Contracture refers to a limitation in the passive range of motion of a joint [1]. It occurs when normally elastic connective tissues are replaced by inelastic fibrous tissue, or due to shortening of skin, fascia, muscle, or joint capsule, or because of mechanical blockage within the joint [1]. This restriction prevents the joint from moving through its full, normal range.

Contractures are often classified by the direction of motion that is limited (e.g., flexion contracture - inability to fully straighten; extension contracture - inability to fully bend; adduction contracture - inability to move away from the midline; abduction contracture - inability to move towards the midline) [1].

Joint contractures can be present at birth (congenital) or develop later in life (acquired) [1].

- Congenital Contractures: Often result from abnormal development (hypoplasia) of muscles, joints, or associated tissues during gestation (e.g., congenital torticollis, clubfoot, arthrogryposis) [1].

- Acquired Contractures: Can arise from various causes [1, 2]:

- Neurogenic: Resulting from neurological disorders or injuries affecting the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves (leading to muscle imbalance, spasticity, or flaccidity).

- Post-Traumatic: Following injuries like fractures (especially intra-articular), dislocations, severe sprains, crush injuries, or burns. Scar tissue formation, muscle damage, or prolonged immobilization can contribute.

- Inflammatory: Chronic joint inflammation (arthritis) can lead to capsular thickening and restricted motion.

- Ischemic: Lack of blood supply to muscles can cause tissue death and scarring (e.g., Volkmann's ischemic contracture).

Joint Contracture Types

Acquired joint contractures can be classified based on the primary tissue involved [1, 2]:

- Dermatogenic or Cutaneous (Cicatricial): Caused by scarring and loss of elasticity in the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

- Desmogenic: Resulting from shortening or restriction in dense connective tissues like fascia, ligaments, or the joint capsule.

- Myogenic: Originating from muscle shortening, fibrosis, or pathology (e.g., injury, inflammation, ischemia).

- Tendogenic: Caused by shortening, adhesion, or disruption of tendons or their sheaths.

- Arthrogenic: Resulting from pathology within the joint itself, such as adhesions, joint surface incongruity, loose bodies, or osteophytes.

- Neurogenic: Caused by neurological conditions leading to muscle imbalance or abnormal tone (spasticity or flaccidity).

Often, contractures involve multiple tissue types (mixed contractures) [1].

Dermatogenic (Cutaneous/Cicatricial) Joint Contracture

Dermatogenic contractures (also known as cutaneous or cicatricial contractures) result from the loss of skin elasticity due to scarring [1]. This is commonly seen after significant skin loss or damage, such as deep burns (thermal or chemical) or extensive wounds that heal by secondary intention (granulation and contraction) [1].

The resulting scar tissue, particularly hypertrophic scars or keloids, can be thick, inelastic, and constricting [1]. As the scar matures and contracts, it pulls on the surrounding skin and underlying tissues, restricting joint movement across which the scar lies [1]. This can lead to significant functional limitations, such as webbing between fingers, inability to fully extend or flex joints (e.g., elbow, knee, neck), or tethering of limbs to the torso [1].

Desmogenic Joint Contracture

Desmogenic contractures arise from the shortening, thickening, or fibrosis of dense connective tissues like fascia (the sheets surrounding muscles), ligaments, or the joint capsule itself [1]. This often occurs after inflammation, trauma, or surgery involving these structures [1].

Examples include Dupuytren's contracture (fibrosis of the palmar fascia causing finger flexion), adhesive capsulitis ("frozen shoulder" involving thickening and contraction of the shoulder joint capsule), and contractures following ligamentous injury or chronic inflammation like plantar fasciitis [1]. Post-inflammatory fascial changes, for instance after infections near the neck (like peritonsillar abscess or "quinsy"), could potentially contribute to neck stiffness or torticollis, although torticollis is more commonly myogenic or neurogenic [1].

Myogenic Joint Contracture

Myogenic contractures develop due to pathological changes within the muscle tissue itself, leading to shortening or loss of elasticity [1].

Causes include [1]:

- Direct muscle trauma (contusions, tears with subsequent scarring).

- Muscle inflammation (acute or chronic myositis).

- Muscle ischemia (lack of blood supply), leading to muscle death and replacement by fibrous tissue (e.g., Volkmann's ischemic contracture, often seen after compartment syndrome following forearm fractures, especially if complicated by tight casts or swelling). Ischemic contractures are often mixed, involving significant nerve damage as well.

- Congenital muscle disorders.

- Prolonged immobilization in a shortened position can lead to adaptive muscle shortening.

Neurogenic Joint Contracture

Neurogenic contractures result from imbalances in muscle forces acting across a joint due to underlying neurological conditions affecting the central or peripheral nervous system [1].

Mechanisms include [1]:

- Spasticity (Upper Motor Neuron Lesions): Conditions like stroke, cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, or multiple sclerosis can cause increased muscle tone (hypertonicity) and spasticity. If certain muscle groups (e.g., flexors) become significantly more spastic than their antagonists (e.g., extensors), the joint can be pulled into and fixed in a flexed position over time.

- Flaccidity/Weakness (Lower Motor Neuron Lesions): Conditions like peripheral nerve injuries, poliomyelitis, or muscular dystrophies can cause weakness or paralysis of specific muscle groups. Unopposed action by the remaining intact muscles or the effects of gravity can lead to the joint adopting a fixed, contracted position.

- Functional Neurological Disorders (formerly Hysteria): In rare cases, fixed abnormal postures resembling contractures can occur without an underlying organic neurological cause.

The specific pattern depends on the neurological lesion. For example, certain spinal cord injuries might lead to extensor spasm in the lower limbs, while others might cause flexion contractures [1].

Arthrogenic & Tendogenic Joint Contractures

Arthrogenic contractures originate from problems within the joint itself [1]. Causes include intra-articular adhesions (scar tissue forming inside the joint, often after surgery or inflammation), incongruity of the joint surfaces (e.g., after a fracture), loose bodies (fragments of bone or cartilage) mechanically blocking motion, or large osteophytes (bone spurs) impinging on movement [1].

Tendogenic contractures result from issues with tendons or their surrounding sheaths, such as tendon shortening, adhesions between the tendon and its sheath (e.g., after inflammation like tenosynovitis or injury), or disruption of tendon continuity [1].

Postural Adaptations & Occupational Factors:

What might be termed "conditioned reflex" or "professional" contractures often represent adaptive shortening or postural changes rather than true fixed contractures initially [1]. For example [1]:

- A person with a shortened leg may compensate by plantarflexing the foot (equinus posture) to effectively lengthen the limb.

- Limb length discrepancies can lead to pelvic tilt and compensatory scoliosis (spinal curvature).

- A hip flexion contracture can cause compensatory lumbar hyperlordosis (increased lower back curve).

Certain occupations involving repetitive motions, awkward postures, or specific hazards can predispose individuals to developing contractures through various mechanisms (e.g., Dupuytren's in manual laborers, burn contractures in firefighters or chemical workers, tendon injuries in specific trades) [1].

Joint Contracture Diagnosis

The diagnosis of joint contracture involves identifying the limitation in passive range of motion and determining the underlying cause and involved tissues [1]. Key factors influencing the presentation include [1]:

- The underlying cause (trauma, inflammation, neurological condition, burn, etc.).

- The specific joint(s) affected.

- The patient's age (contractures can affect growth in children).

- The duration (acute vs. chronic).

Contractures developing from acute inflammatory processes or trauma may progress rapidly, while those from chronic conditions may develop slowly [1]. Severe underlying disease often leads to more pronounced contractures [1]. Associated signs may include muscle atrophy above and below the affected joint due to disuse, and in children, limb growth may be affected [1].

Diagnostic steps include [1, 3]:

- Medical History & Consultation: Understanding the onset, progression, associated symptoms, previous injuries, or underlying conditions.

- Physical Examination: Precise measurement of passive and active range of motion using a goniometer. Assessing muscle strength, tone, sensation, and palpating for scar tissue or bony blocks.

- Imaging:

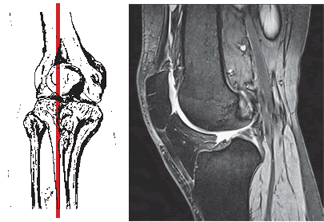

- X-rays: To evaluate bony alignment, joint space, osteophytes, or intra-articular pathology contributing to arthrogenic contracture.

- CT Scan: Provides better detail of bone structure and joint congruity.

- MRI: Best for evaluating soft tissues like muscles, tendons, ligaments, joint capsule, and identifying scar tissue or neurological causes.

- Ultrasound: Can assess tendons, muscles, and guide interventions.

- Nerve Conduction Studies / EMG: May be used to evaluate suspected neurogenic causes.

Joint Contracture Treatment

Treatment aims to restore or maximize functional range of motion, relieve pain, and address the underlying cause [1]. Options include conservative management and surgery [1].

Conservative Treatment: Often the first line, especially for less severe or developing contractures [1].

- Prevention: Crucial aspect involves early mobilization after injury/surgery, proper positioning, and managing inflammation/spasticity [1].

- Stretching: Passive range of motion (PROM) exercises, active-assisted range of motion (AAROM), prolonged static stretching [1, 4].

- Splinting/Casting [1, 4]:

- Static Splints: Hold the joint at its maximum attainable range.

- Dynamic Splints: Apply a low-load, prolonged stretch via springs or elastic bands.

- Serial Casting: Applying a series of casts, each gradually increasing the joint's range.

- Physical Therapy [1, 4]: Includes stretching protocols, strengthening exercises for antagonist muscles, joint mobilization (manual therapy), modalities like heat (to increase tissue extensibility before stretching) or ultrasound.

- Medications: Pain relievers (NSAIDs, analgesics). Muscle relaxants or botulinum toxin injections for spasticity-related contractures [1].

- Therapeutic Injections: Corticosteroids for associated inflammation; enzymatic agents (e.g., collagenase for Dupuytren's) in specific cases [1].

Operative (Surgical) Treatment: Indicated when conservative measures fail to achieve functional goals or for severe, fixed contractures [1, 4].

- Release Procedures: Cutting or lengthening the contracted tissues [1, 4].

- Tenotomy/Tendon Lengthening: Releasing or lengthening tight tendons (e.g., Z-plasty).

- Capsulotomy: Releasing a tight joint capsule.

- Myotomy/Muscle Release: Releasing tight muscles.

- Fasciectomy: Excising contracted fascia (e.g., Dupuytren's).

- Skin Release/Grafting: Releasing tight scar tissue, often requiring skin grafts or flaps for coverage (for dermatogenic contractures).

- Osteotomy: Cutting and realigning bone to improve joint position if bony deformity contributes to the contracture [1].

- Arthroplasty (Joint Replacement): Considered if the joint surface is severely damaged and contributes to the contracture (arthrogenic component) [1, 4].

- Arthrodesis (Joint Fusion): Rarely used for contracture itself, but may be an option for a severely damaged, painful joint fixed in a non-functional position [1, 4].

Post-operative rehabilitation, including intensive physical therapy and often splinting, is critical to maintain the range of motion gained surgically and prevent recurrence [1, 4].

Differential Diagnosis of Joint Stiffness/Immobility

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Joint Contracture (Fibrous/Bony Ankylosis) | Fixed limitation of passive range of motion. Develops over time after injury, inflammation, immobilization, or neurological issue. Bony: complete rigidity. Fibrous: minimal/painful motion. | Clinical exam confirms limited passive ROM. X-ray shows joint space loss/bone bridging (bony) or may be normal/narrowed (fibrous). CT/MRI defines extent. |

| Arthrofibrosis (Post-traumatic/Post-surgical Stiffness) | Significant loss of motion developing after injury or surgery, but joint is not truly fused. Due to capsular/soft tissue adhesions and scarring. | Clinical exam. X-ray usually shows preserved (though possibly narrowed) joint space. MRI may show thickened capsule/adhesions. |

| Severe Osteoarthritis | Gradual onset pain/stiffness, worse with activity. Crepitus. Reduced range of motion due to pain, osteophytes, capsular tightness, but usually not completely fixed unless end-stage. | X-ray: Joint space narrowing, osteophytes, sclerosis. MRI shows cartilage loss. |

| Active Inflammatory Arthritis (e.g., RA, Septic) | Pain, swelling, warmth, redness. Marked limitation of active and passive motion due to pain and effusion/inflammation. Fever possible (septic). | Clinical signs of inflammation. Joint aspiration (WBC, crystals, culture). Elevated ESR/CRP. Specific autoantibodies. Imaging shows effusion/synovitis. |

| Locked Joint (Mechanical Block) | Sudden inability to fully extend or flex (true locking). Often due to displaced meniscus tear or loose body. May have clicking/catching history. | Clinical history and exam. X-ray may show loose body. MRI confirms meniscus tear or loose body. |

| Muscle Spasm / Guarding | Severe pain causes involuntary muscle contraction limiting passive/active motion. Improves significantly with analgesia/anesthesia. Underlying joint allows motion when relaxed. | Clinical exam. Response to relaxation/pain relief. Imaging usually normal. |

| Heterotopic Ossification | Abnormal bone growth in soft tissues around joint after trauma/surgery/neuro injury. Causes progressive stiffness. | X-ray shows extrarticular bone formation. CT/Bone scan helpful. |

| Neurological Conditions (Spasticity/Rigidity) | Increased muscle tone resists passive movement (velocity-dependent in spasticity; constant in rigidity). May lead to fixed contracture over time. Associated neuro signs. | Neurological exam. Brain/spine imaging to identify underlying lesion. EMG. |

References

- Skinner HB, McMahon PJ. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics. 5th ed. McGraw Hill; 2014. Chapter 2: Arthritis & Related Conditions & Chapter on specific joint trauma/reconstruction.

- Brukner P, Khan K. Brukner & Khan's Clinical Sports Medicine. 5th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017. Chapters on specific joint injuries and contractures.

- Resnick D, Kransdorf MJ. Bone and Joint Imaging. 3rd ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2005. Chapters on specific joints and disease processes.

- Canale ST, Beaty JH. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2017. Chapter 4: Joint Contractures.

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone