Metabolic bone disease

Metabolic Bone Disease: Overview and Bone Structure

To understand metabolic bone diseases, it's essential to first examine the structure and function of bone itself [1].

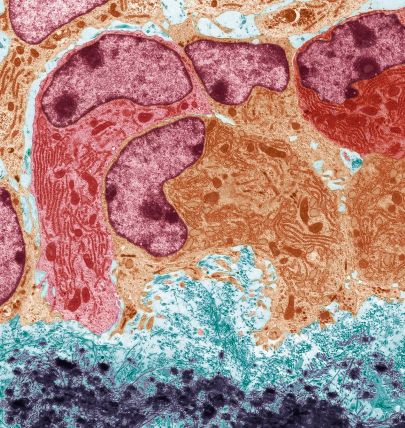

Bone is a dynamic, specialized connective tissue. Like other connective tissues, it comprises cells embedded within an extracellular matrix [1]. This matrix has two main components:

- Organic Matrix (Osteoid): Makes up about 30-35% of bone mass. It primarily consists of proteins, with Type I collagen accounting for about 90-95% of the organic component, forming the structural fibrillar framework [1]. Other important non-collagenous proteins include osteocalcin, osteonectin, osteopontin, and various growth factors, which play roles in mineralization and cell regulation [1].

- Inorganic (Mineral) Component: Comprises about 65-70% of bone mass. This is primarily composed of calcium phosphate crystals in the form of hydroxyapatite [Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂], which provides bone its hardness and rigidity [1]. Magnesium and other trace minerals are also present [1].

The cellular components of bone are responsible for its formation, maintenance, and resorption [1]:

- Osteoblasts: Bone-forming cells that synthesize and secrete the organic osteoid matrix and regulate its mineralization.

- Osteocytes: Mature osteoblasts that become embedded within the mineralized bone matrix. They are interconnected by cellular processes (canaliculi) and act as mechanosensors, playing a crucial role in regulating bone remodeling in response to mechanical stress and hormonal signals.

- Osteoclasts: Large, multinucleated cells responsible for bone resorption (breakdown). They secrete acids and enzymes that dissolve the mineral and degrade the organic matrix.

Bone Remodeling and Metabolic Bone Diseases

The calcified bone matrix is not inert; it undergoes continuous remodeling throughout life [1, 2]. This process involves the coordinated action of osteoclasts resorbing old or damaged bone and osteoblasts forming new bone in its place [1]. This constant turnover, known as "bone remodeling" or "bone turnover," allows bone to adapt to mechanical stresses, repair microdamage, and serve as a crucial reservoir for calcium and phosphate, maintaining mineral homeostasis in the body [1, 2].

Metabolic Bone Diseases arise when there is an imbalance in this tightly regulated cycle of bone remodeling or disruptions in mineral metabolism (calcium, phosphate, vitamin D) [1, 2]. Impaired regulation or activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts leads to abnormalities in bone mass, structure, mineralization, or strength [1]. Common examples of metabolic bone diseases include:

- Osteoporosis: Characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration, leading to increased fragility and fracture risk. Results from an imbalance where bone resorption exceeds formation [1, 2].

- Osteomalacia (Rickets in children): Defective mineralization of newly formed bone matrix (osteoid), usually due to severe vitamin D deficiency or phosphate depletion, resulting in soft, weak bones [1, 2].

- Hyperparathyroidism: Excessive parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion (primary, secondary, or tertiary) leads to increased bone resorption, potentially causing bone pain, fractures, and characteristic bone changes (osteitis fibrosa cystica in severe primary hyperparathyroidism; renal osteodystrophy in secondary hyperparathyroidism due to kidney disease) [1, 2].

- Paget's Disease of Bone: A focal disorder of accelerated and disorganized bone remodeling, leading to enlarged, structurally weak, and deformed bones susceptible to fracture, pain, and arthritis [1, 2].

- Neoplastic Processes: Bone tumors (primary or metastatic) or hematologic malignancies (like multiple myeloma) can disrupt normal bone structure and metabolism, causing bone pain, fractures, and hypercalcemia [1].

Differential Diagnosis of Bone Pain / Fragility

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Lab / Imaging Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoporosis | Usually asymptomatic until fracture occurs (vertebral compression, hip, wrist). Loss of height, kyphosis possible. Low bone mass. | Labs (Calcium, Phosphate, PTH, Vit D, Alk Phos) usually normal. DXA scan confirms low bone density (T-score ≤ -2.5). X-rays show osteopenia, fractures. |

| Osteomalacia / Rickets | Bone pain (often diffuse), muscle weakness, difficulty walking, fractures (esp. pseudofractures/Looser zones). Bowing deformities in children (rickets). Due to defective mineralization. | Low/normal Calcium, low Phosphate, high Alk Phos, low 25(OH)Vit D, often high PTH (secondary hyperpara). X-rays show osteopenia, pseudofractures, characteristic changes in growth plates (rickets). |

| Primary Hyperparathyroidism | Often asymptomatic, discovered via routine hypercalcemia. Can cause bone pain, fractures, kidney stones, constipation, fatigue, depression ("stones, bones, groans..."). | High Calcium, low/normal Phosphate, high PTH. High urine calcium. X-rays may show subperiosteal resorption, osteopenia, brown tumors (rarely). Parathyroid imaging (US, Sestamibi) identifies adenoma/hyperplasia. |

| Secondary/Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism (Renal Osteodystrophy) | History of chronic kidney disease. Bone pain, fractures, muscle weakness. Secondary: Ca low/normal, Phos high, PTH high. Tertiary: Ca high, Phos high/normal, PTH very high. | Lab pattern as above. X-rays show features of renal osteodystrophy (resorption, sclerosis - e.g., "rugger jersey spine", "salt & pepper skull"). |

| Paget's Disease of Bone | Often asymptomatic, found incidentally on X-ray or via high Alk Phos. Can cause bone pain (often deep, aching), deformity (bowing), fractures, arthritis in adjacent joints, warmth over affected bone, hearing loss (skull involvement). Focal disorder. | Markedly elevated Alkaline Phosphatase (bone-specific). Normal Calcium, Phosphate, PTH. X-rays show characteristic mixed lytic/sclerotic lesions, bone expansion, cortical thickening. Bone scan shows increased uptake in affected areas. |

| Bone Metastases / Multiple Myeloma | Bone pain (often worse at night), pathological fractures, hypercalcemia (esp. with extensive mets or myeloma). History of primary cancer (for mets). Fatigue, anemia, renal failure (myeloma). | X-rays show lytic or blastic lesions. Bone scan usually positive (except myeloma). MRI sensitive. Serum/urine protein electrophoresis, free light chains (myeloma). PSA (prostate). Biopsy confirms malignancy. High Calcium, suppressed PTH (if hypercalcemia of malignancy). |

| Osteomyelitis | Localized bone pain, fever, swelling, redness, tenderness. History of recent infection, surgery, trauma, or IV drug use possible. | Elevated WBC, ESR/CRP. Blood cultures may be positive. X-ray changes lag (periosteal reaction, destruction). MRI most sensitive early. Bone scan positive. Biopsy/culture confirms infection. |

| Fibromyalgia | Widespread musculoskeletal pain (not truly bone pain), fatigue, sleep disturbance. Multiple tender points. No objective signs of bone/joint disease. | Clinical diagnosis. Labs and imaging typically normal. |

References

- Favus MJ, ed. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 8th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- Rosen CJ, ed. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 9th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2019. (More recent edition if citing specific newer details).

- Bilezikian JP, ed. The Parathyroids: Basic and Clinical Concepts. 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2015.

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone