Shoulder dislocation (shoulder slip)

Shoulder Dislocation (Glenohumeral Joint) Overview

Shoulder dislocation, specifically of the glenohumeral joint, is the most common major joint dislocation [1]. This high frequency is due to several factors: 1) the shoulder's extensive range of motion required for various activities, and 2) the anatomical structure, where the large humeral head articulates with the relatively small and shallow glenoid fossa (socket) of the scapula [1, 2]. The joint capsule and surrounding ligaments, particularly the anteroinferior portion, are relatively weak compared to the forces they can experience [1].

Mechanism of Anterior Dislocation (Most Common Type): The most frequent mechanism involves a fall onto an outstretched arm or a force applied to the arm when it is abducted (raised away from the body), extended, and externally rotated [1, 2]. This position creates leverage, forcing the humeral head against the weaker anteroinferior aspect of the joint capsule and the glenoid labrum (cartilaginous rim) [1]. Tearing these structures allows the humeral head to displace out of the glenoid fossa, typically moving anteriorly and inferiorly initially [1].

The tension from ligaments and muscle spasm might initially hold the humeral head in an inferior position (luxatio erecta - arm held straight up), but more commonly, the weight of the arm and muscle pull (especially pectoralis major and subscapularis) cause the arm to adduct (fall towards the body) [1]. This pulls the humeral head medially (inwards) and often slightly superiorly, where it comes to rest anterior to the glenoid, usually under the coracoid process of the scapula [1]. This position places it near the brachial plexus nerves and axillary artery [1].

Anterior shoulder dislocations are subclassified based on the final position of the humeral head [1]:

- Subglenoid: Head rests inferior to the glenoid fossa.

- Subcoracoid: Head rests anterior to the glenoid and inferior to the coracoid process (most common type).

- Subclavicular: Head rests medial to the coracoid process and inferior to the clavicle (less common, higher energy).

Other mechanisms include direct blows to the posterior shoulder or forceful muscle contractions (e.g., during seizures or electric shocks) [1].

Posterior Shoulder Dislocation: This is much less common (2-4% of shoulder dislocations) [1, 2]. It typically results from a direct blow to the anterior shoulder, pushing the humeral head backward, or from forceful internal rotation and adduction (e.g., during a seizure) [1]. The humeral head comes to rest posterior to the glenoid fossa, often in the subacromial or subspinous space [1]. The clinical presentation can be subtle and easily missed [1, 2].

Because anterior dislocations are overwhelmingly more common, the following descriptions primarily refer to this type [1].

Diagnostic Symptoms of Shoulder Joint Dislocation

Anterior Dislocation Symptoms [1, 2]:

- Severe pain and inability to move the affected arm.

- The patient typically supports the injured arm with the opposite hand, holding it slightly abducted and externally rotated.

- Visible deformity: Loss of the normal rounded contour of the shoulder ("squared-off" appearance).

- Prominence of the acromion laterally.

- A palpable gap or hollow beneath the acromion where the humeral head should be.

- The axis of the humerus points towards the axilla (armpit) or medially towards the coracoid process.

- Attempts at passive movement, especially adduction and internal rotation, are met with significant pain and resistance (muscle guarding/spasm).

- The displaced humeral head may be palpable anteriorly in the axilla or below the coracoid process.

Associated Complications & Findings [1, 2]:

- Neurovascular Injury: Damage or compression of the axillary nerve (supplies the deltoid muscle and sensation over the lateral shoulder) is common (up to 40%). Less frequently, other parts of the brachial plexus or the axillary artery can be injured. A thorough neurovascular exam is essential. Axillary nerve injury can manifest as deltoid weakness (difficulty abducting the arm) or numbness over the "regimental badge" area.

- Bony Injuries:

- Bankart Lesion: Avulsion (tear) of the anteroinferior glenoid labrum, often with a small fragment of the glenoid bone (Bony Bankart). This destabilizes the joint and increases the risk of recurrence.

- Hill-Sachs Lesion: A compression fracture or defect on the posterolateral aspect of the humeral head, caused by impaction against the anterior glenoid rim during dislocation.

- Greater Tuberosity Fracture: The greater tuberosity (attachment site for rotator cuff muscles) can fracture and displace, especially in older patients.

- Rotator Cuff Tears: Can occur concurrently, particularly in older individuals.

- Hemarthrosis: Bleeding into the joint causes swelling and bruising, which may track down the arm.

These associated injuries, particularly Bankart lesions and significant Hill-Sachs defects, contribute to the high rate of recurrent shoulder dislocations (shoulder instability), especially in younger, active individuals [1, 2]. Early or strenuous activity after inadequate healing also increases recurrence risk [1].

The prognosis after a first-time shoulder dislocation is generally good with appropriate treatment, but the risk of recurrence and potential long-term issues like instability or arthritis increases with associated injuries and patient age/activity level [1, 2].

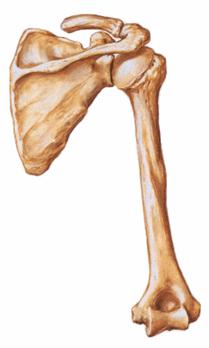

Anatomy of the shoulder joint (posterior view), showing the relationship between the humerus, scapula (shoulder blade), and clavicle [3].

Treatment of Shoulder (Glenohumeral Joint) Dislocation: Reduction & Surgery

Acute, uncomplicated shoulder dislocations should be reduced (relocated) as soon as possible, ideally within hours [1, 2]. Delay makes reduction more difficult due to increasing muscle spasm and swelling [1]. Reduction becomes very difficult or impossible after several weeks to a month [1].

Video demonstrating a technique for shoulder joint reduction, often performed under procedural sedation or with intra-articular local anesthetic injection [2].

Numerous techniques exist for closed reduction (without surgery) [1, 2]. The choice depends on clinician preference, patient condition, and available resources [1]. Adequate analgesia and muscle relaxation are key to success [1, 2]. Common methods include [1, 2]:

- Traction-Countertraction (e.g., Hippocratic/Cooper Modification): The classic method involves applying steady longitudinal traction to the arm while an assistant provides counter-traction (e.g., with a sheet around the chest). Gentle rotation or leverage (historically, the physician's heel in the axilla, though less common now due to potential risks) may be used.

- Stimson Technique: Patient lies prone with the affected arm hanging off the table, weights attached to the wrist to provide gentle, sustained traction.

- External Rotation Method (Kocher - modified): While historically described with forceful maneuvers, modern modifications emphasize gentle external rotation with the arm adducted, followed by abduction/forward elevation, and then internal rotation to guide the head back into the glenoid. *Caution: Original Kocher maneuver had higher fracture/nerve injury risk.*

- Scapular Manipulation: With the patient prone or seated, an assistant applies traction while the clinician manipulates the scapula (rotating the inferior tip medially) to help reposition the glenoid relative to the humeral head.

- Milch Technique: Slow abduction and external rotation of the arm overhead, often with direct pressure on the humeral head.

- FARES Method (Fast, Reliable, and Safe): Continuous gentle longitudinal traction with slow, oscillating abduction/adduction and external/internal rotation movements.

- Janelidze Technique: Similar to Stimson, patient prone with arm hanging, allowing gravity and muscle relaxation to aid reduction, potentially with gentle rotation applied by the clinician.

Successful reduction is usually indicated by a palpable or audible "clunk" and immediate pain relief, with restoration of the shoulder's rounded contour [1]. Post-reduction X-rays are mandatory to confirm concentric reduction and rule out associated fractures [1, 2]. A thorough neurovascular re-assessment is performed [1, 2].

Post-Reduction Management: The shoulder is typically immobilized in a sling (often in slight internal rotation) for a period (ranging from 1 to 4 weeks, depending on age and injury severity) to allow soft tissues to heal [1, 2]. Early, gentle range-of-motion exercises are started progressively, followed by strengthening exercises (especially for the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers) under the guidance of a physical therapist [1, 2].

Chronic/Irreducible Dislocations: Dislocations unreduced for several weeks (e.g., up to 3 months) become increasingly difficult to manage [1]. Fibrous tissue fills the glenoid, and muscles contract [1]. Attempts at closed reduction may still be made, sometimes after prolonged traction [1]. If closed reduction fails or if there are associated issues (like large fractures), open surgical reduction may be required [1]. However, surgery on chronic dislocations carries higher risks of neurovascular injury and stiffness [1]. Sometimes, if a stable pseudo-joint (neartrosis) forms and provides acceptable function, surgery may be avoided [1].

Recurrent Dislocations (Shoulder Instability): Patients experiencing multiple dislocations often have underlying anatomical damage (Bankart lesion, Hill-Sachs defect, capsular laxity) [1, 2]. While they may learn to self-reduce, recurrent instability is problematic and increases the risk of arthritis [1]. Surgical intervention is often recommended, especially for young, active individuals [1, 2]. Common surgical approaches aim to restore stability by [1, 4]:

- Arthroscopic or Open Bankart Repair: Reattaching the torn labrum and tightening the stretched capsule/ligaments.

- Capsular Shift/Plication: Surgically tightening the loose joint capsule.

- Remplissage Procedure: Filling a large Hill-Sachs defect with soft tissue (infraspinatus tendon) to prevent engagement.

- Latarjet Procedure (Coracoid Transfer): A bone block procedure for significant glenoid bone loss, transferring the coracoid process to the anterior glenoid rim to provide a bony buttress.

- Other Procedures: Including muscle/tendon transfers or fascial reconstructions in specific situations.

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Shoulder Injury

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Glenohumeral Dislocation (Anterior/Posterior) | Obvious deformity (squared-off shoulder), arm held fixed, severe pain, inability to move shoulder. History of trauma/fall. | X-ray (AP and axillary/scapular Y views) confirms humeral head displaced from glenoid. Check neurovascular status. CT may show associated fractures (Hill-Sachs, Bankart). |

| Proximal Humerus Fracture | Often fall in elderly. Severe pain, swelling, extensive bruising (ecchymosis) tracking down arm. Inability to move arm. Shoulder contour may be preserved unless significantly displaced. Crepitus possible. | X-ray (shoulder series) shows fracture of humeral head, neck, or tuberosities. Glenohumeral joint congruent. CT defines fracture complexity. |

| Clavicle Fracture | Direct blow or fall onto shoulder. Pain, deformity, tenderness directly over clavicle. Patient supports arm. | X-ray confirms clavicle fracture. Glenohumeral joint normal. |

| Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint Separation | Fall onto point of shoulder. Pain localized to top of shoulder (AC joint). Visible step-off deformity in higher grades. | X-ray (AP +/- weighted views) shows widening/displacement at AC joint. |

| Rotator Cuff Tear (Acute Large Tear) | Often significant trauma or fall in older adult. Severe pain, significant weakness especially with abduction and external rotation. May have felt a tear/pop. Unable to lift arm (pseudoparalysis). | Clinical exam shows profound weakness. X-ray usually normal or shows chronic changes. Ultrasound or MRI confirms large rotator cuff tendon tear(s). |

| Shoulder Impingement / Bursitis (Acute) | Sudden onset pain often after overuse or minor trauma. Pain with overhead activities, typically localized anterolaterally. Painful arc of motion. Usually no gross deformity. | Clinical exam (positive impingement tests). X-ray usually normal. Ultrasound/MRI may show bursitis or minor cuff tendinopathy. |

| Calcific Tendinitis (Acute Phase) | Excrutiating, sudden onset pain, often waking patient from sleep. Severe limitation of motion due to pain. Usually involves supraspinatus tendon. | X-ray may show fluffy calcium deposit within rotator cuff tendon. Ultrasound confirms deposit and associated inflammation/bursitis. |

References

- Rockwood CA, Matsen FA III, Wirth MA, Lippitt SB, eds. The Shoulder. 4th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2009. Chapters on Shoulder Instability and Dislocations.

- Skinner HB, McMahon PJ. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics. 5th ed. McGraw Hill; 2014. Chapter 5: Shoulder & Humerus Trauma.

- Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray's Anatomy for Students. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Chapter 7: Upper Limb.

- Hovelius L, Josefsson PO, Sandström B, et al. Nonoperative treatment of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in patients forty years of age and younger. A prospective twenty-five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 May;90(5):945-52. (Example study on outcomes/recurrence).

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone