Knee joint and patellar dislocation

Knee Joint (Tibiofemoral) Dislocation Overview

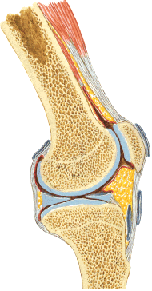

Knee dislocations generally refer to three main types of instability: dislocation or subluxation of the main tibiofemoral joint (where the tibia meets the femur), issues involving the menisci (cartilage pads), and dislocation of the patella (kneecap) [1].

Complete Tibiofemoral Dislocation: This is a severe, limb-threatening orthopedic emergency where the tibia loses all contact with the femur [1, 2]. It involves extensive ligamentous damage, typically rupture of multiple major ligaments (often including both cruciate ligaments and at least one collateral ligament) [1, 2]. These dislocations are classified based on the direction of tibial displacement relative to the femur (anterior, posterior, lateral, medial, or rotatory) [1].

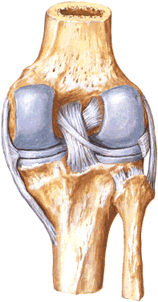

The knee's stability against front-to-back (anteroposterior) displacement primarily relies on the powerful intra-articular cruciate ligaments [2, 4]:

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL): Runs from the anterior tibia to the posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. It primarily resists anterior tibial translation and becomes taut in extension and during knee flexion.

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL): Runs from the posterior tibia to the medial femoral condyle. It is the primary restraint to posterior tibial translation and prevents hyperextension.

Mechanisms [1, 2]:

- Anterior Dislocation: Often caused by severe hyperextension, tearing the PCL first, followed by other structures including the ACL.

- Posterior Dislocation: Typically results from a direct blow to the anterior tibia with the knee flexed (e.g., dashboard injury), tearing the PCL. Complete posterior dislocation requires further ligament disruption, including the ACL.

Complete tibiofemoral dislocations require tremendous force and invariably involve rupture of multiple major ligaments (ACL, PCL, collateral ligaments) [1, 2]. Lateral dislocations are even rarer and imply disruption of both cruciate and both collateral ligaments [1].

The clinical presentation of a complete knee dislocation is usually dramatic, with gross deformity, severe pain, and instability [1, 2]. However, some dislocations may spontaneously reduce before medical evaluation, making diagnosis challenging [1]. A significant knee effusion (hemarthrosis – bleeding into the joint) is typical due to ligamentous tears [1]. The most critical concern with tibiofemoral dislocations is the high risk (up to 40-50%) of associated popliteal artery injury, which can threaten limb viability [1, 2]. Careful neurovascular assessment is mandatory [1, 2]. Peroneal nerve injury is also common [1].

Reduction: Prompt closed reduction under sedation or anesthesia is required [1, 2]. This usually involves longitudinal traction with direct pressure to guide the tibia back into alignment [1]. Post-reduction stability is assessed, and thorough vascular evaluation (including ankle-brachial index - ABI, and potentially angiography) is performed [1, 2].

Fixation/Treatment: After reduction, the knee is typically immobilized in slight flexion (e.g., with a hinged knee brace or external fixator) [1, 2]. Definitive treatment almost always involves surgical reconstruction of the torn ligaments, often performed in a staged manner once swelling subsides [1, 2].

Knee Joint (Tibiofemoral) Subluxation

Knee subluxation refers to a partial dislocation where the joint surfaces momentarily separate but then return to a near-normal position, often spontaneously [1]. It implies significant ligamentous injury but less severe than a full dislocation [1]. Anterior or posterior subluxations are more common than complete dislocations [1].

Subluxations often result from rupture of a single cruciate ligament (ACL or PCL) possibly combined with damage to collateral ligaments or the capsule, leading to knee instability [1]. Patients often report a feeling of the knee "giving way" or shifting [1].

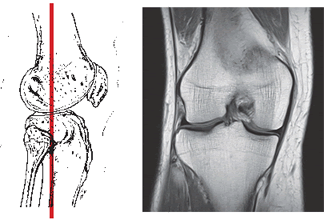

Diagnosis relies on the patient's history (mechanism of injury, sensation of instability), physical examination findings, and imaging [1]. Clinical tests assess ligament integrity [1]:

- Anterior Drawer Test / Lachman Test: Assess ACL integrity. A positive test ("drawer sign") indicates increased anterior tibial translation relative to the femur, suggesting ACL rupture.

- Posterior Drawer Test: Assesses PCL integrity. Increased posterior tibial translation suggests PCL rupture.

Tenderness may be present over the ligament attachments (e.g., below the patellar ligament for ACL tibial attachment, or in the popliteal fossa for PCL tibial attachment) [1]. Hemarthrosis is common [1].

Patients often become aware of the instability themselves, describing the "drawer" phenomenon or feeling the tibia shift forward or backward during certain movements (e.g., pivoting, stopping suddenly, walking downstairs) [1].

Acute management of subluxations often involves RICE (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) and immobilization (brace) initially, followed by rehabilitation [1]. Treatment focuses on restoring stability [1].

Due to the increased participation in sports like skiing, soccer, and others involving pivoting and cutting motions, knee subluxations and associated ligament injuries (especially ACL tears) are increasingly common [1]. Chronic instability from untreated ligament injuries can lead to recurrent subluxations, further cartilage damage, and early osteoarthritis [1].

Treatment for chronic instability often involves surgical reconstruction of the torn ligament(s), commonly using arthroscopic techniques (minimally invasive surgery) to rebuild the ACL or PCL using grafts [1].

Diagnostic methods commonly used include [1, 4]:

- Clinical Examination (history, stability tests)

- X-rays (to rule out fractures)

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the knee joint (Gold standard for visualizing ligaments, menisci, cartilage)

- Computed Tomography (CT) scan (Less common for ligaments, more for bony detail if fracture is suspected)

Meniscus Injury (Often Termed 'Dislocation')

While true "dislocation" of the entire meniscus is not anatomically precise, the term is sometimes loosely used to refer to significant meniscal tears where a fragment displaces into the joint, causing mechanical symptoms [1]. The menisci are C-shaped fibrocartilage pads (medial and lateral) that act as shock absorbers and stabilizers between the femur and tibia [4].

Meniscal tears are very common knee injuries, often occurring during twisting movements on a flexed knee with the foot planted [1]. Degenerative tears can also occur with minimal trauma in older individuals [1].

A specific type of tear that can mimic a "dislocation" is a bucket-handle tear, where a large, longitudinally torn fragment flips into the center of the joint (intercondylar notch), often causing the knee to lock (inability to fully extend) [1]. Other tear patterns can also cause catching, clicking, or locking [1].

MRI is the primary imaging modality for accurately diagnosing meniscal tears and differentiating them from ligament injuries or other causes of knee pain and mechanical symptoms [1, 4].

Treatment depends on the tear type, size, location, patient age, and activity level, ranging from conservative management (physiotherapy) to arthroscopic surgery (meniscectomy - removal of the torn part, or meniscal repair) [1].

Patellar (Kneecap) Dislocation

Patellar dislocation occurs when the kneecap (patella) slides completely out of its groove (trochlear groove) on the front of the femur [1]. It most commonly dislocates laterally (towards the outside of the knee) [1].

Several factors can predispose individuals to patellar dislocation and instability [1, 5]:

- Anatomical Factors: Genu valgum ("knock-knees"), a shallow trochlear groove, a high-riding patella (patella alta), flattened femoral condyles (especially laterally), ligamentous laxity (loose ligaments).

- Muscle Imbalance: Weakness of the medial quadriceps muscle (Vastus Medialis Obliquus - VMO).

- Trauma: A direct blow to the knee or a sudden twisting motion.

Once a primary dislocation occurs, the risk of recurrent (habitual) dislocation increases significantly due to damage to the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), the primary soft tissue restraint against lateral displacement [1, 5].

Video illustrating a reduction technique for a lateral patellar dislocation [5]. Anesthesia or sedation may be used for comfort.

The diagnosis of an acute patellar dislocation is usually obvious if the patella remains dislocated laterally [1]. Patients experience intense pain, inability to bend the knee, and a visible deformity [1]. Often, however, the patella spontaneously reduces (relocates) as the knee is straightened, either by the patient instinctively or with assistance [1]. In these cases, the patient reports a sensation of the knee "going out of place" and then "popping back in," followed by pain, swelling, and tenderness, especially along the medial (inner) edge of the patella where the MPFL may be torn or stretched [1].

Patients with recurrent dislocations often learn to self-reduce the patella by straightening the knee while applying medial pressure to the kneecap [1].

Video demonstrating reduction of a tibiofemoral (main knee joint) dislocation, a distinct and more severe injury than patellar dislocation, typically requiring significant force and procedural sedation/anesthesia [1].

Treatment for a first-time patellar dislocation usually involves closed reduction (if not already spontaneously reduced), followed by immobilization (brace or cylinder cast) for a period, and then extensive physiotherapy focusing on strengthening the quadriceps (especially VMO), improving flexibility, and proprioception [1, 5].

Recurrent dislocations often require surgical intervention to stabilize the patella [1, 5]. Numerous surgical procedures exist, aiming to repair or reconstruct the MPFL, realign the extensor mechanism (e.g., tibial tubercle osteotomy), or address underlying anatomical abnormalities (e.g., trochleoplasty) [5]. The choice of procedure depends on the specific factors contributing to the instability [5].

Conservative therapeutic options, particularly for rehabilitation after reduction or surgery, or for milder instability, include [1]:

- Physical Therapy / Therapeutic Exercises (focusing on VMO strengthening, core stability, proprioception)

- Bracing (patellar stabilizing braces)

- Activity Modification

- Pain Management (NSAIDs, ice)

- Manual Therapy (soft tissue mobilization)

- Massage (adjunctive for muscle soreness)

- Therapeutic Injections (less common for primary instability, sometimes used for associated pain/inflammation)

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Knee Injury

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Tibiofemoral Dislocation | High-energy trauma. Gross knee deformity, severe pain, instability, inability to bear weight. Large effusion (hemarthrosis). High risk of neurovascular injury (popliteal artery). | X-ray confirms gross displacement of tibia relative to femur. Urgent reduction needed. Requires thorough vascular assessment (ABI, +/- angiography). MRI later confirms multi-ligament rupture (ACL, PCL, collaterals). |

| Patellar Dislocation | Often non-contact twisting injury or direct blow. Patella visibly displaced laterally (if not spontaneously reduced). Sensation of kneecap "popping out". Medial patellar tenderness. Apprehension test positive. | Clinical diagnosis often clear if dislocated. X-ray (AP, lateral, sunrise views) confirms patellar position, rules out fracture (patella, lateral femoral condyle). MRI assesses MPFL tear, cartilage damage. |

| Cruciate Ligament Tear (ACL/PCL) | Often non-contact pivoting (ACL) or dashboard-type injury (PCL). Audible "pop" common. Hemarthrosis, feeling of instability ("giving way"). | Clinical tests (Lachman, Anterior/Posterior Drawer) show instability. X-ray usually normal (may show Segond fracture with ACL). MRI confirms ligament tear, associated injuries (meniscus, bone bruise). |

| Meniscal Tear | Twisting injury often. Joint line pain, clicking, catching, locking (esp. bucket-handle tear). Effusion may be delayed/mild. | Clinical exam (joint line tenderness, McMurray's test). X-ray usually normal. MRI confirms tear type/location. |

| Collateral Ligament Sprain/Tear (MCL/LCL) | Valgus (MCL) or Varus (LCL) force. Pain/tenderness directly over the ligament on medial (MCL) or lateral (LCL) side of knee. Instability with varus/valgus stress testing. | Clinical exam. X-ray usually normal. MRI confirms tear grade/location. |

| Patellar/Quadriceps Tendon Rupture | Sudden force during jumping/landing. Inability to actively extend the knee. Palpable defect in the tendon (above patella for quad, below for patellar). High-riding (quad) or low-riding (patellar) patella. | Clinical exam. X-ray shows abnormal patellar position. Ultrasound or MRI confirms tendon rupture. |

| Tibial Plateau Fracture / Distal Femur Fracture | Significant trauma often. Severe pain, swelling, hemarthrosis, inability to bear weight. May have associated ligamentous injury. | X-ray shows fracture line involving tibial plateau or distal femur. CT scan often needed to fully characterize articular involvement. |

References

- Skinner HB, McMahon PJ. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics. 5th ed. McGraw Hill; 2014. Chapter 7: Knee & Leg Trauma.

- Wascher DC, Dvirnak PC, DeCoster TA. Knee dislocation: initial assessment and implications for treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(7):525-9. (Or similar review on tibiofemoral dislocations).

- Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz RW, Heckman JD. Rockwood and Green's Fractures in Adults. 8th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. Volume 2, Chapter 49: Dislocations and Soft Tissue Injuries of the Knee.

- Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray's Anatomy for Students. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Chapter 6: Lower Limb (Section on Knee Joint).

- Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Stone ML, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of acute patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2004 Jul-Aug;32(5):1114-21.

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone