Knee joint osteoarthritis (gonarthrosis)

Knee Osteoarthritis (Gonarthrosis): Overview and Causes

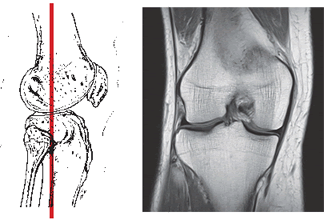

Knee Osteoarthritis (OA), also known as gonarthrosis or degenerative joint disease of the knee, is a common condition characterized primarily by the progressive degeneration and loss of articular cartilage within the knee joint [1, 2]. This cartilage breakdown leads to subsequent changes in the underlying bone, including the formation of bone spurs (osteophytes) at the joint margins, joint space narrowing, and changes in bone density (subchondral sclerosis). These structural alterations result in joint pain, stiffness, deformation, and impaired knee motion [1, 2].

Joint diseases are broadly grouped into inflammatory (like rheumatoid arthritis, gout) and degenerative conditions [1]. Osteoarthritis is the most common degenerative type [2]. While secondary inflammation can occur in OA, the primary process is wear and tear and degeneration, distinct from primary inflammatory or autoimmune arthropathies where inflammation drives the joint damage [1]. Causes and risk factors for knee OA include:

- Age (risk increases significantly with age)

- Obesity (increased load on joints)

- Previous knee injury (e.g., meniscus tears, ligament injuries, fractures involving the joint)

- Genetics / Family history

- Female gender (higher prevalence, especially after menopause)

- Occupational or recreational activities involving repetitive stress on the knees

- Certain metabolic diseases (less common)

Knee Osteoarthritis (Gonarthrosis): Diagnosis

In osteoarthritis, degenerative processes lead to the breakdown of articular cartilage. Enzymes and inflammatory mediators can contribute to this degradation [1]. As cartilage wears away, the underlying bone becomes exposed and stressed, leading to pain, thickening (sclerosis), cyst formation, and the development of osteophytes (bone spurs) at the joint margins [1, 2]. These structural changes contribute to joint stiffness, pain, and reduced function.

To clarify the nature and extent of the changes in the knee joint, the following diagnostic steps are usually required [1, 2]:

- Clinical Evaluation: Includes a detailed medical history (symptoms like pain type/timing, stiffness duration, mechanical symptoms, impact on function, risk factors) and a physical examination (assessing range of motion, tenderness, swelling/effusion, crepitus, alignment, stability, gait).

- Imaging Studies:

- X-rays: Weight-bearing views are standard. Key findings include joint space narrowing (especially medial or lateral compartment), osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts. Essential for assessing severity and alignment.

- MRI of the knee joint: Not routinely needed for typical OA diagnosis but useful for evaluating associated soft tissue pathology (meniscal tears, ligament injuries), assessing cartilage status in more detail, identifying bone marrow lesions, or ruling out other conditions (like avascular necrosis).

- CT of the knee joint: Less common for OA diagnosis; primarily used for assessing complex bony anatomy or fractures.

- Laboratory Tests: Generally not helpful for diagnosing primary OA. Blood tests (like ESR, CRP, RF, Anti-CCP) are usually normal but may be ordered to rule out inflammatory arthritis if suspected.

- Joint Aspiration (Arthrocentesis): May be performed if there is significant effusion or suspicion of infection or crystal arthropathy (gout/pseudogout). OA synovial fluid is typically non-inflammatory (low white cell count, no crystals).

Differential Diagnosis of Knee Pain

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis (Gonarthrosis) | Gradual onset pain, worse with activity, brief morning stiffness (<30 min). Crepitus, bony enlargement. Older age, obesity, prior injury common risk factors. | X-ray: Joint space narrowing, osteophytes, sclerosis. Labs usually normal. Synovial fluid non-inflammatory. |

| Inflammatory Arthritis (e.g., Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriatic Arthritis, Gout, Pseudogout, Reactive Arthritis) | Pain often present at rest, prolonged morning stiffness (>30-60 min). Joint swelling, warmth, redness. May affect other joints or have systemic symptoms. Gout/Pseudogout: Acute, severe flares. | Elevated ESR/CRP. Specific autoantibodies (RF, anti-CCP). Synovial fluid inflammatory (+/- crystals for gout/pseudogout). X-ray may show erosions. |

| Meniscal Tear | Often history of twisting injury. Joint line pain, clicking, catching, locking, giving way. Effusion common. | Clinical exam (joint line tenderness, McMurray's test). MRI confirms tear. X-ray usually normal unless associated OA. |

| Ligament Sprain/Tear (ACL, PCL, MCL, LCL) | History of specific trauma (e.g., pivot, hyperextension, valgus/varus force). Feeling of instability, "pop" at injury. Effusion (often large hemarthrosis with ACL). | Clinical stability tests (Lachman, Drawer, Varus/Valgus stress). X-ray usually normal (may show avulsion). MRI confirms ligament tear. |

| Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome | Anterior knee pain, worse with stairs, squatting, prolonged sitting ("theater sign"). Often in younger, active individuals. May have clicking/grinding under kneecap. | Clinical exam (patellar tracking, compression tests). Imaging often normal. |

| Bursitis (Prepatellar, Pes Anserine) | Localized swelling, tenderness, warmth over the bursa (anterior kneecap for prepatellar; medial aspect below joint line for pes anserine). Often related to kneeling or overuse. | Clinical diagnosis based on location of findings. Ultrasound can confirm bursal fluid/inflammation. |

| Septic Arthritis | Acute onset severe pain, swelling, warmth, redness. Fever common. Marked inability to move joint or bear weight. Medical emergency. | Joint aspiration diagnostic (high WBC, positive Gram stain/culture). Elevated blood inflammatory markers. |

Knee Joint Osteoarthritis (Gonarthrosis): Treatment

Treatment for knee osteoarthritis is tailored to the severity of cartilage degeneration and symptoms, aiming to reduce pain, improve function, and slow progression. Options include [1, 2]:

- Drug therapy: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain and inflammation; simple analgesics like acetaminophen; topical agents (NSAIDs, capsaicin).

- Intra-articular injections: Corticosteroids for short-term inflammation/pain relief; hyaluronic acid (viscosupplementation) to improve joint lubrication; platelet-rich plasma (PRP) (effectiveness still under investigation).

- Manual therapy: Including myofascial release and gentle joint mobilization techniques to improve mobility and reduce pain.

- Physiotherapy: Modalities like Ultrasound (UHF), Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), heat/cold therapy for symptom relief.

- Therapeutic Exercise: Crucial for strengthening quadriceps, hamstrings, and hip muscles; improving range of motion and flexibility; low-impact aerobic conditioning.

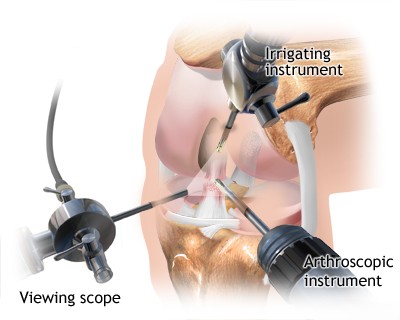

- Surgery: Considered for severe OA unresponsive to conservative treatment. Options include [4]:

- Arthroscopy: Limited role for primary OA; mainly for mechanical symptoms from associated meniscal tears or loose bodies.

- Osteotomy: Realigning the knee joint (usually for younger patients with unicompartmental OA).

- Arthroplasty (Knee Replacement): Partial or total knee replacement is highly effective for end-stage OA.

In cases with associated mechanical symptoms from significant meniscal tears or ligamentous instability (though ligament rupture is not typical of primary OA), arthroscopic surgery may be indicated to address those specific issues [4].

In the acute phase of arthritis or post-injury, managing swelling and inflammation is key (e.g., RICE, NSAIDs, physiotherapy modalities like UHF) [1]. Maintaining muscle strength and joint mobility through appropriate exercise and physical therapy is crucial throughout the treatment course [1].

Bracing or splinting can provide support and reduce stress on the affected joint during activity [1].

References

- Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR. Kelley & Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2017. Chapters on Osteoarthritis and Principles of Therapy.

- Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014 Jun;43(6):701-12. (Or cite specific guidelines like ACR/EULAR).

- Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray's Anatomy for Students. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Chapter 6: Lower Limb (Section on Knee Joint).

- Resnick D, Kransdorf MJ. Bone and Joint Imaging. 3rd ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2005. Chapter on Knee Imaging.

- Canale ST, Beaty JH. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Arthritis and Arthroplasty.

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone