Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction and osteoarthritis

What are Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)?

Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD), often commonly referred to as "TMJ" after the joint itself, encompass a group of conditions causing pain and dysfunction in the jaw joint (temporomandibular joint - TMJ) and the muscles responsible for jaw movement (masticatory muscles) (1, 2).

These disorders can affect a person's ability to speak, eat, chew, swallow, make facial expressions, and even breathe. TMD is multifactorial, often involving issues with the joint itself, the muscles of mastication, or both (1, 3).

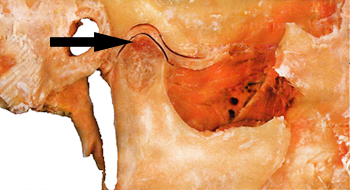

One specific type of TMD involves degenerative changes within the joint, known as Temporomandibular Joint Osteoarthritis (TMJ OA) or arthrosis. This involves the breakdown of the cartilage covering the articular surfaces and potential changes in the underlying bone and the articular disc (meniscus) (4).

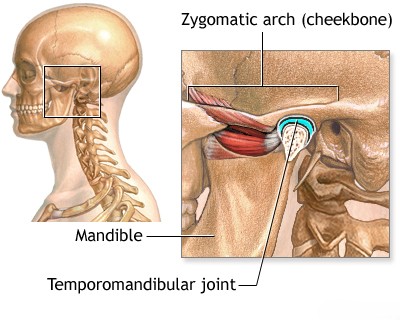

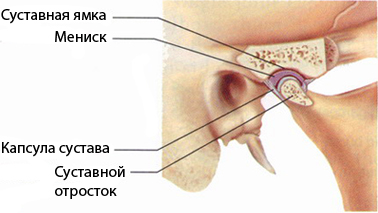

Anatomy of the TMJ

The TMJ is a complex joint connecting the lower jaw (mandible) to the temporal bone of the skull, located just in front of each ear. It allows for hinge-like opening and closing movements as well as sliding motions forward, backward, and side-to-side (1).

Key components include:

- The mandibular condyle (the rounded end of the lower jaw).

- The articular fossa and eminence of the temporal bone (the socket).

- An articular disc (meniscus) made of cartilage, situated between the condyle and fossa, facilitating smooth movement and absorbing shock.

- Ligaments that stabilize the joint.

- Surrounding muscles of mastication (e.g., masseter, temporalis, pterygoids) that power jaw movements.

Types of TMD

TMDs are commonly categorized into three main groups, which can occur alone or in combination (1, 2, 3):

- Myofascial Pain Disorders: Characterized by pain and dysfunction originating primarily from the muscles of mastication. Features include muscle tenderness, fatigue, pain referred to other areas (like the temples, neck, or ears), and sometimes limited jaw opening due to muscle tightness or spasm. Myofascial trigger points (sensitive spots in muscles) can be a significant source of pain (3). This aligns somewhat with the historical "MBD syndrome" concept mentioned in older literature.

- Internal Derangements (Disc Disorders): Involve problems with the position or function of the articular disc within the TMJ. Common examples include:

- Disc Displacement with Reduction: The disc is displaced (usually forward) when the mouth is closed but returns ("reduces") to its normal position upon opening, often causing a clicking or popping sound (1).

- Disc Displacement without Reduction: The disc is displaced and does not return to its normal position upon opening, often leading to limited jaw opening ("closed lock") and pain (1).

- Degenerative Joint Disease (Arthritis): Involves deterioration of the joint structures.

- Osteoarthritis (OA) / Arthrosis: The most common form. Characterized by breakdown of articular cartilage, changes in the underlying bone (e.g., flattening of the condyle, osteophytes), and sometimes secondary inflammation (synovitis). Often associated with joint crepitus (grating sounds), pain, and limited function (4).

- Inflammatory Arthritis: Conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis can also affect the TMJ, causing inflammation and potential erosion.

Causes and Risk Factors

TMD is generally considered multifactorial, with no single cause identified for most cases. Contributing factors may include (1, 2, 3):

- Bruxism: Clenching or grinding of teeth, especially during sleep, can overload the joints and muscles.

- Trauma: Direct injury to the jaw, TMJ, or head/neck muscles (e.g., whiplash, impact).

- Malocclusion: While debated, significant issues with how teeth fit together may contribute in some individuals, potentially altering joint loading or muscle activity.

- Arthritis: Osteoarthritis or systemic inflammatory arthritis affecting the TMJ.

- Stress and Psychosocial Factors: Can lead to increased muscle tension and parafunctional habits (like clenching).

- Postural Factors: Poor head and neck posture may contribute to muscle strain.

- Joint Hypermobility: Increased laxity in ligaments may predispose some individuals.

Symptoms

Symptoms can vary widely but often include (1, 2, 4):

- Pain or tenderness in the jaw joint area, face, neck, shoulders, or in/around the ear, especially when chewing, speaking, or opening the mouth wide.

- Jaw muscle stiffness or fatigue.

- Limited ability to open the mouth wide or locking ("getting stuck") of the jaw.

- Clicking, popping, or grating sounds (crepitus) in the jaw joint when opening or closing the mouth (may or may not be painful).

- Difficulty chewing or a sudden uncomfortable bite, feeling as though the upper and lower teeth are not fitting together properly.

- Headaches (often resembling tension headaches), earaches, or neck aches.

- Facial swelling on the affected side.

Historically, criteria like Laskin's (pain, muscle tenderness, joint sounds, limited/deviated opening) were used for diagnosis of related syndromes (3), but current diagnosis considers a broader range of factors.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis involves a comprehensive evaluation (1, 2, 7):

- Detailed History: Understanding the nature, location, onset, duration, and triggers of pain; presence of joint sounds, locking, limited opening, headaches, ear symptoms, parafunctional habits (clenching/grinding), stress levels, and previous trauma or dental work.

- Clinical Examination:

- Palpation: Assessing tenderness in the TMJs (laterally and sometimes through the ear canal, though direct palpation pain is more common in inflammatory conditions) and the muscles of mastication (masseter, temporalis, pterygoids).

- Range of Motion: Measuring the extent of jaw opening (normal is typically >40mm), lateral movements, and protrusion, noting any pain or deviation.

- Joint Sounds: Listening for clicks, pops, or crepitus during jaw movement.

- Occlusal Assessment: Examining how the teeth fit together, although its direct causal link to TMD is complex.

- Cervical Spine Examination: Assessing neck posture and muscle tenderness, as neck issues can contribute to or mimic TMD symptoms.

- Imaging Studies: Not always necessary but used to evaluate joint structures, especially if internal derangement or osteoarthritis is suspected, or if symptoms are severe or unresponsive to initial treatment (1, 7).

- Panoramic Radiograph (OPG): Provides a general overview of teeth, mandible, and TMJs, but detail of the joint itself is limited. Useful for screening for gross pathology.

- Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT): Offers detailed 3D images of the bony components of the TMJ, excellent for assessing degenerative changes (OA), fractures, or bony abnormalities (7).

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The best modality for visualizing soft tissues, particularly the position and condition of the articular disc, joint effusion (inflammation), and surrounding tissues (7). Essential for diagnosing disc displacements accurately.

- Standard X-rays of the TMJ have limited utility compared to CBCT or MRI.

- Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD): Standardized criteria used by researchers and clinicians to classify TMD into specific diagnostic categories based on history and clinical findings (2).

Treatment

Treatment aims to relieve pain, restore function, and reduce contributing factors. A conservative, reversible approach is typically recommended first (1, 8).

- Patient Education and Self-Care:

- Understanding the condition and its multifactorial nature.

- Eating soft foods, avoiding wide yawning, gum chewing, and hard/chewy foods.

- Applying moist heat or cold packs to affected areas.

- Stress management and relaxation techniques.

- Awareness and reduction of parafunctional habits (clenching/grinding).

- Physical Therapy:

- Exercises (gymnastics) to improve jaw mobility, coordination, and muscle strength/relaxation.

- Postural training for the head and neck.

- Manual therapy techniques (muscle manipulation) for joint mobilization and muscle release.

- Modalities like ultrasound, heat/cold, or TENS for pain relief (though evidence varies).

- Oral Appliances (Splints or Occlusal Guards): Custom-fitted devices worn over the teeth (usually at night) to protect against bruxism, reduce muscle tension, and sometimes reposition the jaw or unload the joint (1, 8). Their effectiveness and mechanism are debated for different TMD types.

- Medications:

- NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) for pain and inflammation.

- Analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen).

- Muscle relaxants (short-term) for acute muscle spasm.

- Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) for chronic pain and sleep disturbance.

- Sometimes anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin) for neuropathic pain components.

- Injections (Drug Injection):

- Trigger point injections (local anesthetic, sometimes with steroid) into tender muscle points for myofascial pain (3).

- Intra-articular injections (corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid) into the TMJ space for inflammation or osteoarthritis (1, 4).

- Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections into masticatory muscles (e.g., masseter, temporalis) for severe myofascial pain or bruxism (use is often off-label and requires expertise) (1).

- Surgery (Surgical Treatment): Considered only for a small percentage of patients with specific structural joint problems (e.g., severe internal derangement, advanced osteoarthritis) who have failed extensive conservative management. Procedures range from minimally invasive arthrocentesis (joint lavage) and arthroscopy to more complex open joint surgery or joint replacement (1).

Management often involves collaboration between dentists, physicians, physical therapists, and sometimes pain specialists or psychologists.

Differential Diagnosis

Pain in the TMJ region can arise from various sources (1, 9):

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Dental Problems | Toothache (pulpitis, abscess), periodontal disease, impacted wisdom teeth. Pain often localized to a tooth, sensitive to temperature or pressure. Dental examination is key. |

| Ear Problems | Otitis media/externa (ear infection), Eustachian tube dysfunction. Associated hearing changes, discharge, fullness. Otoscopic examination needed. |

| Sinusitis | Inflammation of paranasal sinuses. Facial pressure/pain (often cheeks, forehead), nasal congestion/discharge, sometimes toothache. |

| Salivary Gland Disorders | Parotitis (inflammation/infection of parotid gland), sialolithiasis (stones). Swelling/pain over the gland, often related to meals. |

| Neuropathic Pain / Neuralgias | Trigeminal neuralgia (sharp, electric shock-like pain in nerve distribution), glossopharyngeal neuralgia, atypical facial pain. Pain quality and triggers differ from typical TMD. |

| Giant Cell Arteritis (Temporal Arteritis) | Inflammation of large/medium arteries, typically >50 yrs old. Headache (temporal), scalp tenderness, jaw claudication (pain with chewing), visual symptoms. Requires urgent diagnosis/treatment. Elevated ESR/CRP common. |

| Cervical Spine Disorders | Neck pain/stiffness, headaches (cervicogenic), referred pain to the face or jaw region. |

| Tumors/Neoplasms | Rare causes of pain/dysfunction in the TMJ region. Persistent, progressive symptoms, neurological deficits, or bony changes on imaging may raise suspicion. |

References

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). TMJ (Temporomandibular Joint and Muscle Disorders). Updated March 2023. Available from: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/health-info/tmj

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28(1):6-27. doi:10.11607/jop.1151

- Graff-Radford SB, Bassiur JP. Temporomandibular Disorders and Headaches. Neurol Clin. 2016;34(2):525-537. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2015.12.003 (Discusses myofascial component)

- Tanaka E, Detamore MS, Mercuri LG. Degenerative disorders of the temporomandibular joint: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dent Res. 2008;87(4):296-307. doi:10.1177/154405910808700406

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Vol 1. Upper Half of Body. 2nd ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1999. (Classic reference on trigger points, including pterygoids - cited for context of original text)

- Okeson JP. Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019. (Standard textbook)

- Ahmad M, Hollender L, Anderson Q, et al. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD): development of image analysis criteria and examiner reliability for image analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(6):844-860. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.023

- List T, Axelsson S. Management of TMD: evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(6):430-451. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02089.x

- Scrivani SJ, Keith DA, Kaban LB. Temporomandibular disorders. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(25):2693-2705. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0802472 (Includes differential diagnosis)

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone