Nerve blocks and trigger point injection

- Introduction: Injection Therapies for Pain

- What are Nerve Blocks?

- What are Trigger Point Injections (TPIs)?

- Common Types and Examples

- Indications for Injections

- Procedure Overview & Medications Used

- Contraindications

- Potential Risks and Side Effects

- Focus on Lidocaine (Common Local Anesthetic)

- Differential Diagnosis (Pain Mimicking Conditions)

- References

Introduction: Injection Therapies for Pain

Nerve blocks and trigger point injections are common interventional procedures used to diagnose and manage various pain conditions. They involve injecting medication, typically a local anesthetic often combined with a corticosteroid, into specific target locations to alleviate pain and sometimes break cycles of inflammation or muscle spasm (1, 2).

What are Nerve Blocks?

A Nerve Block involves injecting medication very close to a specific nerve or group of nerves (plexus) (1, 3). The primary goal is to interrupt pain signals traveling along that nerve pathway.

- Purpose: Can be diagnostic (to identify if a specific nerve is the source of pain by seeing if numbing it provides relief) or therapeutic (to provide prolonged pain relief, reduce inflammation around the nerve, or facilitate physical therapy) (1, 3).

- Mechanism: Local anesthetics (like lidocaine or bupivacaine) temporarily block nerve conduction. Corticosteroids may be added to reduce inflammation around the nerve (1).

What are Trigger Point Injections (TPIs)?

A Trigger Point Injection (TPI) involves injecting medication directly into a myofascial trigger point (2, 4). A trigger point is a hyperirritable spot within a taut band of skeletal muscle that is painful upon compression and can give rise to characteristic referred pain, tenderness, and sometimes autonomic phenomena.

- Purpose: Therapeutic; aims to inactivate the trigger point, relieve localized and referred pain, and release muscle tightness (2, 4).

- Mechanism: The injection itself (using just anesthetic, sometimes called "wet needling", or even just the needle without medication, "dry needling") can mechanically disrupt the trigger point. The local anesthetic helps reduce immediate pain and may help break the pain-spasm cycle. Corticosteroids are sometimes added, though their benefit directly into muscle trigger points is debated (2, 4).

The temporary pain relief from the anesthetic (often 20-60 minutes, depending on the agent) can allow muscles to relax and may initiate a process of restoring normal muscle tone and reducing pain long-term (4).

The intended effect of these therapeutic injections is often to relieve muscle spasm, increase range of motion in nearby joints (by reducing pain and muscle guarding), and decrease the intensity of pain both locally and in areas of referred or radicular pain (1, 4).

Common Types and Examples

Injection therapies encompass a wide range of procedures:

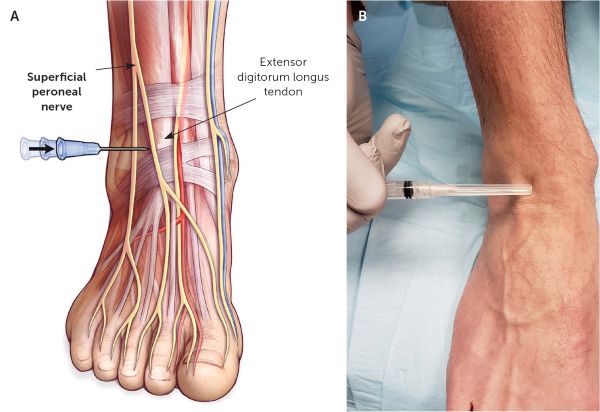

- Peripheral Nerve Blocks: Targeting specific nerves in the limbs or trunk (e.g., median nerve block for carpal tunnel, occipital nerve block for headaches, intercostal nerve block for chest wall pain) (1, 3).

- Neuraxial Blocks (Spinal Area):

- Epidural Steroid Injections: Medication injected into the epidural space around the spinal cord/nerve roots, commonly used for radicular pain (sciatica) from disc herniation or spinal stenosis (1, 5).

- Selective Nerve Root Blocks (Transforaminal): More targeted injection around a specific exiting nerve root, often used diagnostically and therapeutically for radiculopathy (1, 5).

- Facet Joint Injections / Medial Branch Blocks: Targeting the small joints of the spine (facet joints) or the nerves supplying them (medial branches), used for axial back/neck pain related to facet joint arthritis/inflammation (1, 5).

- Joint Injections: Injecting medication (often corticosteroid) directly into a joint space (e.g., knee, shoulder, hip, sacroiliac joint, TMJ) to treat arthritis or inflammation (1).

- Trigger Point Injections (TPIs): Targeting myofascial trigger points in muscles throughout the body (e.g., trapezius, gluteals, neck muscles) associated with myofascial pain syndromes or fibromyalgia-related tender points (2, 4).

- Sympathetic Blocks: Targeting parts of the sympathetic nervous system (ganglia, plexuses) for certain chronic pain conditions like Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) (1).

Indications for Injections

These procedures may be considered as part of a comprehensive treatment plan for various conditions, including (1, 2, 3, 4, 5):

- Nerve Entrapment Syndromes (e.g., Carpal Tunnel Syndrome)

- Radiculopathy (Nerve root pain, e.g., sciatica from disc herniation)

- Certain types of Headaches (e.g., occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic headache)

- Neuralgias (e.g., Intercostal Neuralgia, post-herpetic neuralgia)

- Myofascial Pain Syndromes / Fibromyalgia (TPIs)

- Joint Pain (e.g., Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis - intra-articular injections)

- Bursitis / Tendinopathies (e.g., Shoulder Impingement/Periarthrosis - subacromial injection)

- Facet Joint Syndrome (Axial neck or back pain)

- Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

- Temporomandibular Joint Disorders (TMJ arthrosis/dysfunction - intra-articular or muscle injections)

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) (Sympathetic blocks)

Procedure Overview & Medications Used

The specific technique varies greatly depending on the target structure. General steps often include:

- Patient positioning for optimal access and comfort.

- Identifying the target site using anatomical landmarks, ultrasound guidance, or fluoroscopy (X-ray guidance), especially for deeper or more precise blocks (1, 3, 5).

- Cleaning the skin with an antiseptic solution.

- Injecting the medication(s) using an appropriate needle and syringe.

- Commonly used medications include:

- Local Anesthetics: Lidocaine (Xylocaine, Lignocaine), Bupivacaine, Ropivacaine. Provide temporary numbness and pain relief (1).

- Corticosteroids: Methylprednisolone, Triamcinolone, Betamethasone, Dexamethasone. Provide anti-inflammatory effects that may last weeks to months (1). Often mixed with local anesthetic.

- Saline: Sometimes used for TPIs or hydrodissection.

Contraindications

Contraindications depend on the specific procedure and medications used, but general ones include (1, 6):

- Patient refusal.

- Infection at the injection site or systemic infection (sepsis).

- Allergy to the medications being used (local anesthetics, corticosteroids, contrast dye if used).

- Bleeding disorders or therapeutic anticoagulation (relative contraindication, requires careful consideration and management, especially for deeper blocks or neuraxial procedures).

- Severe systemic illness or instability.

- Specific contraindications for neuraxial blocks: Increased intracranial pressure, certain neurological conditions.

- Specific contraindications for certain local anesthetics: Severe heart block (e.g., AV block grade 2 or 3 without pacemaker), severe bradycardia, severe hypotension, certain cardiac conditions (cardiogenic shock), history of malignant hyperthermia (for some agents), severe liver dysfunction (for amide anesthetics like lidocaine), myasthenia gravis (can be exacerbated).

Potential Risks and Side Effects

While generally safe when performed by trained professionals, potential risks exist (1, 6):

- Common/Minor: Pain or soreness at the injection site, bruising, temporary numbness or weakness from the local anesthetic.

- Less Common: Infection (superficial or deep), bleeding (hematoma), nerve injury (temporary or rarely permanent), vasovagal reaction (fainting), allergic reaction to medication.

- Medication-Specific (Corticosteroids): Facial flushing, temporary increase in blood sugar, mood changes, insomnia, fluid retention, potential tissue atrophy or skin discoloration at injection site (especially superficial), rare risk of adrenal suppression with frequent/high doses.

- Medication-Specific (Local Anesthetics): Systemic toxicity (if accidentally injected into a blood vessel or excessive dose used) causing CNS effects (dizziness, metallic taste, tinnitus, seizures) or cardiovascular effects (arrhythmias, hypotension, cardiac arrest). This is rare with proper technique and dosing.

- Procedure-Specific Risks: For deeper blocks or neuraxial procedures, risks include pneumothorax (lung collapse), dural puncture headache (spinal headache), epidural hematoma or abscess, injury to adjacent structures.

Focus on Lidocaine (Common Local Anesthetic)

Lidocaine (also known as Lignocaine or Xylocaine) is a widely used amide local anesthetic.

- Usage: Employed in various concentrations (commonly 0.5%, 1%, or 2%) for infiltration, peripheral nerve blocks, trigger point injections, and sometimes epidural anesthesia (1). Its onset is relatively rapid, and duration is intermediate (typically 60-120 minutes, longer if mixed with epinephrine).

- Epinephrine Addition: Sometimes added to lidocaine solutions (e.g., 1:200,000) to cause local vasoconstriction. This decreases systemic absorption, prolongs the duration of the block, and reduces bleeding (1). Caution is needed in areas with end-arteries (fingers, toes, nose, penis).

- Dosing Considerations: The maximum safe dose depends on the concentration, site of injection (vascularity affects absorption), use of epinephrine, and patient factors (age, weight, liver function). Exceeding maximum doses increases the risk of systemic toxicity (1, 6). *Specific dosing regimens should always be determined by the performing clinician based on the specific procedure and patient.*

- Side Effects/Toxicity: Local effects include temporary numbness/tingling. Systemic toxicity (rare with proper use) primarily affects the CNS (early signs: perioral numbness, metallic taste, dizziness, tinnitus; severe: seizures, coma) and cardiovascular system (bradycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias, cardiac arrest) (1, 6). Severe liver dysfunction impairs lidocaine metabolism, increasing risk.

- Contraindications: Known hypersensitivity, severe heart block (unless paced), severe liver disease (relative).

Note: The detailed dosing provided in the original text for various types of anesthesia (terminal, antiarrhythmic, etc.) is outside the scope of a general overview of nerve blocks/TPIs and is omitted here for clarity and safety.

Differential Diagnosis (Pain Mimicking Conditions)

Pain conditions that might lead to consideration of blocks/injections often need to be differentiated from other sources:

| Pain Location/Type | Potential Differential Diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Neck/Shoulder/Arm Pain | Cervical Radiculopathy (requires nerve root block evaluation), Cervical Facet Arthropathy (requires facet/medial branch block evaluation), Rotator Cuff Disease, Adhesive Capsulitis, Myofascial Pain (TPIs), Thoracic Outlet Syndrome, Peripheral Nerve Entrapment (e.g., carpal tunnel). |

| Low Back/Leg Pain | Lumbar Radiculopathy (Sciatica) (requires epidural/selective nerve root block evaluation), Lumbar Facet Arthropathy, Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction, Piriformis Syndrome, Myofascial Pain (TPIs), Hip Pathology (arthritis, bursitis), Spinal Stenosis. |

| Headache | Migraine, Tension-Type Headache, Cluster Headache, Occipital Neuralgia (requires occipital nerve block evaluation), Cervicogenic Headache (may involve facet/nerve blocks or TPIs), TMJ Disorders. |

| Joint Pain | Osteoarthritis, Inflammatory Arthritis (RA, PsA, Gout), Tendinopathy, Bursitis, Ligament Sprain, Internal Derangement (e.g., meniscus tear). Intra-articular or periarticular injections may be considered. |

| Widespread/Muscle Pain | Fibromyalgia (TPIs sometimes used for tender points), Myofascial Pain Syndrome (TPIs are a key treatment), Polymyalgia Rheumatica, Systemic Inflammatory Disease, Vitamin D Deficiency. |

References

- Waldman SD. Atlas of Interventional Pain Management. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2014. (Comprehensive reference for block techniques)

- Alvarez DJ, Rockwell PG. Trigger points: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(4):653-660. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2002/0215/p653.html

- Neal JM, Barrington MJ, Fettiplace MR, et al. The Third American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Practice Advisory on Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity: Executive Summary 2017. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(2):113-123. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000720 (Focuses on anesthetic safety)

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Vol 1. Upper Half of Body. 2nd ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1999. (Classic text on trigger points)

- Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, et al. Comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in the management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12(4):699-802. (Covers spinal injections)

- Management of Chronic Pain Guideline Development Group. NICE guideline [NG193]: Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain. Published April 2021. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193 (Includes discussion on limitations/contraindications for some injections)