Headache and migraine symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

Headache Symptom, Migraine Overview

Headache, medically termed cephalalgia, is a highly common symptom characterized by pain perceived in the head or upper neck region. It is not a single disease entity but can arise from a vast array of underlying causes. These etiologies are broadly categorized into primary headache disorders, such as migraine, tension-type headache, and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs), where the headache itself is the principal disorder, and secondary headaches, which are symptomatic of another condition [1]. Secondary causes involve diseases of the brain and its protective layers (meninges), such as infections (meningitis, arachnoiditis, encephalitis), bleeding (subarachnoid hemorrhage, subdural hematoma), space-occupying lesions (tumors, abscesses), traumatic brain injury, or disorders affecting cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics leading to increased intracranial pressure (ICP) (e.g., hydrocephalus, idiopathic intracranial hypertension) or low CSF pressure (e.g., post-LP headache, spontaneous CSF leak). Headaches can also stem from extracranial issues like disorders of the neck muscles and joints (cervicogenic headache), paranasal sinus diseases (sinusitis), eye conditions (acute glaucoma, refractive errors), dental problems, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction, or systemic conditions including vascular disorders (giant cell arteritis, hypertension, cerebral venous thrombosis), infections, metabolic disturbances, and substance use or withdrawal.

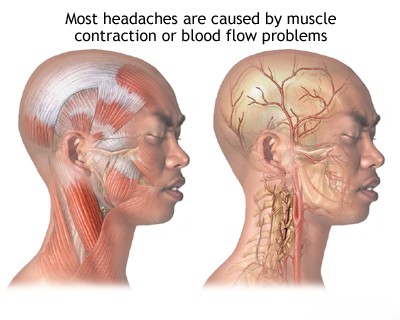

The pain associated with intracranial processes like meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or rapidly expanding tumors often results from irritation or mechanical distortion (stretching, traction) of pain-sensitive intracranial structures. These primarily include the dura mater lining the skull base and parts of the falx/tentorium, and the large arteries (e.g., circle of Willis), veins, and venous sinuses at the base of the brain [2]. These structures are innervated mainly by branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V - supratentorially) and upper cervical spinal nerves (C1-C3 - infratentorially and posterior fossa dura). Mechanical stimulation (pressure, traction) or chemical irritation (e.g., by blood breakdown products in SAH, inflammatory mediators in meningitis) of these nerve endings triggers the headache. Elevated ICP can cause headache by stretching the dura and blood vessels, and potentially by direct pressure effects, though the correlation between absolute ICP level and headache severity is not always direct. Impaired CSF circulation is a key factor in headaches associated with hydrocephalus or mass lesions obstructing CSF pathways.

Vascular factors are strongly implicated in certain headache types. In migraine, complex neurovascular mechanisms involve neuronal hyperexcitability, cortical spreading depression (underlying aura), activation of the trigeminovascular system (release of neuropeptides like CGRP causing vasodilation and neurogenic inflammation), and central pain pathway sensitization [3]. Fluctuations in vascular tone may contribute to pain perception by activating perivascular trigeminal nerve endings. Headaches related to severe hypertension (hypertensive crisis/encephalopathy) or hypotension can also occur due to direct vascular effects or altered autoregulation.

Neuralgia involves irritation, inflammation, or damage to specific nerves supplying the head and neck structures (trigeminal nerve - CN V, glossopharyngeal nerve - CN IX, occipital nerves derived from C2-C3 roots, nervus intermedius). This typically leads to characteristic sharp, shooting, stabbing, electric shock-like, or burning pain confined to the nerve's distribution.

A meticulous description of the headache characteristics (headache history) is fundamental for diagnosis. Key features include:

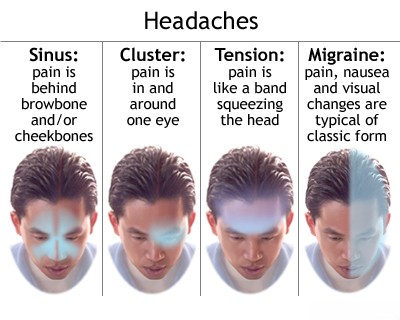

- Quality: How the pain feels (e.g., pressing, tightening like a band, throbbing/pulsating, stabbing, piercing, shooting, burning, dull ache, pressure).

- Location: Where the pain is felt (e.g., unilateral or bilateral, frontal, temporal, occipital, vertex, periorbital, facial). Precise location and radiation pattern are important.

- Intensity: Severity of pain, usually rated on a numerical scale (e.g., 0-10), ranging from mild to severe/incapacitating.

- Onset and Duration: How quickly the headache starts (abrupt/sudden onset like a "thunderclap" raises concern for serious pathology like SAH) versus gradual onset. Duration of individual attacks (seconds, minutes, hours, days) and overall temporal pattern (episodic vs. chronic/constant).

- Frequency: How often headaches occur (e.g., number of headache days per month). Used to classify episodic vs. chronic forms.

- Timing: Relationship to time of day (e.g., waking with headache, worse in afternoon/evening), menstrual cycle, weekends, specific activities or triggers.

- Associated Symptoms: Nausea, vomiting, photophobia (light sensitivity), phonophobia (sound sensitivity), osmophobia (smell sensitivity); aura symptoms (transient visual, sensory, or motor disturbances preceding or accompanying headache, typical of migraine with aura); cranial autonomic symptoms (ipsilateral tearing, conjunctival injection, nasal congestion/rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, forehead/facial sweating, miosis/ptosis, typical of TACs); dizziness, vertigo, neck stiffness, fever.

- Aggravating/Relieving Factors: Effect of routine physical activity, position changes (worse lying down suggests high ICP; worse upright suggests low CSF pressure), coughing/straining (Valsalva), stress, specific foods or drinks (triggers), sleep (often relieves migraine), specific medications.

Headache character provides diagnostic clues: meningeal irritation (meningitis, SAH) often causes severe, constant, diffuse pain with neck stiffness. Trigeminal neuralgia causes brief (< seconds), excruciating, electric shock-like facial pain attacks triggered by innocuous stimuli. Migraine is typically pulsating/throbbing and often unilateral. Tension-type headache is classically described as a bilateral, non-pulsating pressing or tightening sensation ("band-like"). Cluster headache involves excruciatingly severe, unilateral orbital/temporal pain.

Headaches can be persistent (continuous for days or longer) or paroxysmal (occurring in distinct attacks with pain-free intervals). Severe, persistent pain is characteristic of meningeal irritation (though SAH often presents as sudden severe pain initially). Headaches from raised ICP may initially be intermittent or worse in the mornings, becoming more constant and severe as pressure rises.

The presence of meningeal signs (neck stiffness, Kernig's sign, Brudzinski's sign) alongside headache strongly suggests meningeal irritation from infection or blood. Associated focal neurological deficits (weakness, numbness, visual changes, speech difficulty, coordination problems) point towards a structural brain lesion (tumor, stroke, abscess) or specific neurological event.

Diagnostic evaluation often involves considering associated findings: hypertensive retinopathy on fundoscopy suggests hypertension as a factor; focal signs on neurological exam or specific EEG abnormalities might help localize a lesion; CSF analysis confirms infection or bleeding.

Headaches due to increased intracranial pressure (e.g., from hydrocephalus, tumor, IIH) are classically worse with Valsalva maneuvers (coughing, sneezing, straining), bending over, or lying flat, and may be most prominent upon waking in the morning.

Arterial hypertension itself is generally not considered a cause of chronic headache unless BP is severely elevated (hypertensive crisis/encephalopathy). However, poor BP control is a risk factor for stroke and vascular changes that can lead to headache.

Hypotension, particularly postural hypotension, can cause headaches, usually less intense, often dull or diffuse, typically accompanied by lightheadedness, fatigue, and weakness upon standing.

Ocular causes include acute angle-closure glaucoma (sudden, severe unilateral eye pain radiating to head, blurred vision, halos, nausea/vomiting, red eye, fixed mid-dilated pupil - an emergency), uveitis/iritis (eye pain, redness, photophobia), and occasionally uncorrected refractive errors (often causing frontal headache or eye strain ('asthenopia'), typically related to prolonged near work).

Rhinosinusitis causes headache or facial pain/pressure overlying the affected sinus(es), often worse with bending forward, typically associated with nasal symptoms (congestion, discharge, decreased smell). Otitis media can cause ear pain radiating to the ipsilateral head.

Systemic conditions like acute febrile illnesses (influenza, systemic infections), certain endocrine disorders (hypothyroidism), and even severe anemia can be associated with headaches.

Headache and Migraine Classification

Headaches are systematically classified by the International Headache Society (IHS) using the International Classification of Headache Disorders, currently in its 3rd edition (ICHD-3) [1]. This classification is essential for accurate diagnosis, research, and management. The primary division is between:

- Primary Headaches: Where the headache itself is the disorder, not caused by another underlying condition.

- Secondary Headaches: Where the headache is a symptom attributed to another disorder known to cause headache.

- Cranial Neuralgias, Central and Primary Facial Pain, and Other Headaches: Includes facial pain syndromes and headaches not fitting the primary/secondary model neatly.

Correct classification based on detailed history and adherence to ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria is fundamental.

The Primary Headaches (ICHD-3 Classification - Major Categories)

- 1.1 Migraine without aura

- 1.2 Migraine with aura

- 1.2.1 Migraine with typical aura

- 1.2.2 Migraine with brainstem aura (formerly basilar-type)

- 1.2.3 Hemiplegic migraine (Familial/Sporadic)

- 1.2.4 Retinal migraine

- 1.3 Chronic migraine (≥15 headache days/month for >3 months, with ≥8 days having migraine features)

- 1.4 Complications of migraine

- 1.4.1 Status migrainosus (debilitating attack >72 hours)

- 1.4.2 Persistent aura without infarction

- 1.4.3 Migrainous infarction

- 1.4.4 Migraine aura-triggered seizure (Migralepsy)

- 1.5 Probable migraine

- 1.6 Episodic syndromes that may be associated with migraine (Infancy/Childhood precursors)

- 1.6.1 Recurrent gastrointestinal disturbance (Cyclical vomiting syndrome, Abdominal migraine)

- 1.6.2 Benign paroxysmal vertigo

- 1.6.3 Benign paroxysmal torticollis

- 2.1 Infrequent episodic tension-type headache (< 1 day/month)

- 2.2 Frequent episodic tension-type headache (1-14 days/month)

- 2.3 Chronic tension-type headache (≥15 days/month)

- 2.4 Probable tension-type headache

- (Each can be sub-classified based on presence/absence of pericranial tenderness)

- 3.1 Cluster headache (Episodic/Chronic)

- 3.2 Paroxysmal hemicrania (Episodic/Chronic)

- 3.3 Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache attacks (SUNCT/SUNA)

- 3.4 Hemicrania continua

- 3.5 Probable trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia

- 4.1 Primary cough headache

- 4.2 Primary exercise headache

- 4.3 Primary headache associated with sexual activity

- 4.4 Primary thunderclap headache

- 4.5 Cold-stimulus headache

- 4.6 External-pressure headache

- 4.7 Primary stabbing headache

- 4.8 Nummular headache

- 4.9 Hypnic headache

- 4.10 New daily persistent headache (NDPH)

The Secondary Headaches (ICHD-3 Classification - Major Categories)

- 5.1 Acute headache attributed to traumatic injury to the head

- 5.2 Persistent headache attributed to traumatic injury to the head

- 5.3 Acute headache attributed to whiplash

- 5.4 Persistent headache attributed to whiplash

- 5.5 Acute headache attributed to craniotomy

- 5.6 Persistent headache attributed to craniotomy

- 6.1 Headache attributed to ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

- 6.2 Headache attributed to non-traumatic intracranial haemorrhage (ICH, SAH, SDH)

- 6.3 Headache attributed to unruptured vascular malformation (aneurysm, AVM, dural AV fistula, cavernous angioma)

- 6.4 Headache attributed to arteritis (Giant cell arteritis - GCA, Primary angiitis of the CNS - PACNS)

- 6.5 Carotid or vertebral artery pain (attributed to dissection, post-endarterectomy, angioplasty)

- 6.6 Headache attributed to cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT)

- 6.7 Headache attributed to other intracranial arterial process (e.g., RCVS, vasospasm)

- 6.8 Headache attributed to pituitary apoplexy

- 7.1 Headache attributed to high cerebrospinal fluid pressure (Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension - IIH, secondary causes)

- 7.2 Headache attributed to low cerebrospinal fluid pressure (Post-dural puncture, CSF fistula leak, spontaneous intracranial hypotension - SIH)

- 7.3 Headache attributed to non-infectious inflammatory disease (Neurosarcoidosis, aseptic meningitis, lymphocytic hypophysitis, IgG4-related disease)

- 7.4 Headache attributed to intracranial neoplasm (primary brain tumor, metastasis)

- 7.5 Headache attributed to intrathecal injection

- 7.6 Headache attributed to epileptic seizure (ictal, post-ictal)

- 7.7 Headache attributed to Chiari malformation type I (CM1)

- 7.8 Headache attributed to other non-vascular intracranial disorder

- 8.1 Headache induced by acute substance use or exposure (e.g., NO donors, alcohol, cocaine, histamine, CGRP)

- 8.2 Medication-overuse headache (MOH) (resulting from chronic overuse of acute headache medications - analgesics, triptans, opioids, ergots, combination analgesics)

- 8.3 Headache as an adverse event attributed to chronic medication

- 8.4 Headache attributed to substance withdrawal (e.g., caffeine, opioids, estrogen)

- 9.1 Headache attributed to intracranial infection (e.g., bacterial/viral/fungal meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess, subdural empyema)

- 9.2 Headache attributed to systemic infection (e.g., influenza, sepsis, COVID-19)

- 10.1 Headache attributed to hypoxia and/or hypercapnia (e.g., high altitude headache, diving headache, sleep apnoea headache)

- 10.2 Dialysis headache

- 10.3 Headache attributed to arterial hypertension (associated with hypertensive crisis, pheochromocytoma, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia)

- 10.4 Headache attributed to hypothyroidism

- 10.5 Headache attributed to fasting

- 10.6 Cardiac cephalalgia (rare, precipitated by myocardial ischaemia)

- 10.7 Headache attributed to other disorder of homoeostasis

- 11.1 Headache attributed to disorder of cranial bone

- 11.2 Headache attributed to disorder of the neck (Cervicogenic headache)

- 11.3 Headache attributed to disorder of the eyes (e.g., acute glaucoma, refractive errors, eye inflammation)

- 11.4 Headache attributed to disorder of the ears

- 11.5 Headache attributed to rhinosinusitis

- 11.6 Headache attributed to disorder of the teeth or jaws

- 11.7 Headache attributed to temporomandibular disorder (TMD)

- 11.8 Headache or facial pain attributed to inflammation of stylohyoid ligament (Eagle syndrome)

- 12.1 Headache attributed to somatization disorder

- 12.2 Headache attributed to psychotic disorder

Cranial Neuralgias, Central and Primary Facial Pain, and Other Headaches (ICHD-3 Part 3 & Appendix)

- 13.1 Trigeminal neuralgia (Classical, Secondary, Idiopathic)

- 13.2 Glossopharyngeal neuralgia (Classical, Secondary, Idiopathic)

- 13.3 Nervus intermedius neuralgia

- 13.4 Occipital neuralgia

- 13.5 Neck-tongue syndrome

- 13.6 Optic neuritis (Pain associated with)

- 13.7 Headache attributed to ischaemic ocular motor nerve palsy

- 13.8 Tolosa–Hunt syndrome

- 13.9 Paratrigeminal oculosympathetic (Raeder’s) syndrome - & Note: Often considered secondary

- 13.10 Recurrent painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy (RPON)

- 13.11 Burning mouth syndrome (BMS)

- 13.12 Persistent idiopathic facial pain (PIFP)

- 13.13 Central neuropathic pain (e.g., Central post-stroke pain, facial pain attributed to MS)

Note: The Appendix in ICHD-3 lists conditions requiring further research or validation, or whose classification is uncertain. Examples might include concepts previously under "Other Headache Disorders".

Headache and Migraine Diagnosis

The diagnostic approach to headache begins with a comprehensive patient history and neurological examination. For many primary headaches like typical migraine or tension-type headache, a diagnosis can often be made confidently based on the clinical presentation conforming to established diagnostic criteria (e.g., ICHD-3 criteria) [4]. Patients presenting with prolonged, chronic, or acutely severe headaches, or headaches with atypical features or associated neurological signs ("red flags"), warrant further investigation to rule out secondary causes, typically involving consultation with a neurologist or headache specialist.

Differential Diagnosis of Headache

| Category / Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Headaches | ||

| Migraine (with/without aura) | Episodic attacks (4-72h). Usually unilateral, pulsating, moderate/severe pain, aggravated by routine physical activity. Associated nausea and/or vomiting, photophobia AND phonophobia. Aura: transient, reversible neurological symptoms (visual most common) preceding or accompanying headache. | Clinical diagnosis based on ICHD-3 criteria. Normal neurological exam between attacks. Neuroimaging usually normal (only indicated if atypical features or red flags present). |

| Tension-Type Headache (TTH) | Lasts 30min-7days. Bilateral location, pressing/tightening (non-pulsating) quality, mild/moderate intensity. Not aggravated by routine physical activity. EITHER photophobia OR phonophobia may be present, but NOT both; no nausea/vomiting (or mild nausea only). Pericranial tenderness may be present. | Clinical diagnosis based on ICHD-3 criteria. Normal neurological exam. Imaging not usually indicated unless features are atypical. |

| Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (TACs - e.g., Cluster Headache, Paroxysmal Hemicrania, SUNCT/SUNA, Hemicrania Continua) | Group of disorders with strictly unilateral, severe pain (often orbital/supraorbital/temporal). Accompanied by mandatory ipsilateral cranial autonomic symptoms (conjunctival injection, tearing, nasal congestion/rhinorrhea, eyelid oedema, forehead/facial sweating/flushing, sensation of fullness in the ear, miosis/ptosis). Distinct attack duration/frequency patterns differentiate subtypes (see specific table below). | Clinical diagnosis based on specific ICHD-3 criteria for each TAC. MRI needed primarily to rule out secondary causes mimicking TACs (e.g., pituitary adenoma, structural lesions affecting trigeminal pathway/cavernous sinus). Specific treatment responses critical for diagnosis (e.g., oxygen/triptans for CH; indomethacin absolute response for PH & HC). |

| Secondary Headaches (Selected "Red Flag" Examples Requiring Urgent Evaluation) | ||

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) | Sudden onset, severe "thunderclap" headache (reaching maximal intensity within seconds to a minute, "worst headache of life"). Often associated loss/alteration of consciousness, nausea/vomiting, neck stiffness, photophobia. | Urgent non-contrast CT head (high sensitivity within first 6-12 hours). If CT negative but clinical suspicion remains high, Lumbar Puncture (LP) after 6-12 hours shows blood (RBCs) or xanthochromia (bilirubin). CTA/DSA needed to identify source (usually ruptured aneurysm). |

| Meningitis / Encephalitis | Headache (often severe, generalized), fever, neck stiffness (meningismus), photophobia, altered mental status (confusion, lethargy, coma). May have seizures, focal neurological deficits (more common in encephalitis). | LP essential (if safe after imaging excludes major mass effect): CSF analysis shows inflammation (WBC pleocytosis - neutrophils in bacterial, lymphocytes in viral/TB/fungal), altered protein/glucose levels. Gram stain/culture/PCR identifies pathogen. Brain imaging (MRI preferred) may show meningeal enhancement or parenchymal changes (encephalitis). |

| Intracranial Mass (Tumor, Abscess, Large Hematoma) | Headache often progressive, worse in morning or with Valsalva, may awaken from sleep. Nausea/vomiting (signs of raised ICP). Development of focal neurological deficits (weakness, sensory loss, visual changes, aphasia), seizures, personality/cognitive changes depending on location/size. Papilledema on funduscopy. | MRI with contrast is imaging modality of choice, clearly delineates mass lesion, edema, mass effect. CT useful initially in emergencies. Biopsy may be needed for definitive diagnosis of tumor type. |

| Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (IIH) / Secondary Causes of High ICP | Headache (often diffuse, pressure-like, worse with straining/bending), pulsatile tinnitus ("whooshing" sound), transient visual obscurations (vision dims briefly), diplopia (due to CN VI palsy), papilledema on exam. Risk factors for IIH: young, obese women. Can be secondary to CVT, medications (tetracyclines, vitamin A). | Funduscopy confirms papilledema. Neuroimaging (MRI/MRV preferred) needed to exclude structural mass/hydrocephalus/CVT; may show specific signs (empty sella, optic nerve sheath distension/tortuosity, transverse sinus stenosis). LP (performed carefully) confirms elevated opening pressure (>25 cmH2O in adults), with normal CSF composition. |

| Low CSF Pressure Headache (Post-LP, Spontaneous Leak - SIH) | Orthostatic headache: Develops or worsens significantly within minutes of assuming upright posture (sitting/standing), relieved rapidly by lying flat. Often occipital/neck pain. May have nausea, muffled hearing, tinnitus, dizziness. History of recent LP or trauma, or can be spontaneous. | Brain MRI with contrast may show characteristic signs: diffuse pachymeningeal (dural) enhancement, sagging of brainstem/tonsils, subdural fluid collections/hygromas, pituitary enlargement. LP (if performed) shows low opening pressure (<6 cmH2O or even unmeasurable). Spinal imaging (MRI myelography, CT myelography, digital subtraction myelography) may identify the site of CSF leak. |

| Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) / Temporal Arteritis | Age ≥50 usually. New-onset headache (often temporal, can be diffuse), scalp tenderness (esp. temporal arteries - may be thickened/tender/non-pulsatile), jaw claudication (pain with chewing), abrupt visual symptoms (amaurosis fugax - transient monocular blindness, diplopia, permanent vision loss - ophthalmologic emergency!). Systemic symptoms common (fever, malaise, weight loss, polymyalgia rheumatica - shoulder/hip girdle pain/stiffness). | Markedly elevated ESR (>50 mm/hr) and/or CRP are highly suggestive. Temporal artery biopsy showing vasculitis is gold standard (but may be negative due to skip lesions). Prompt initiation of high-dose corticosteroids is essential to prevent irreversible blindness, often started based on clinical suspicion before biopsy results. |

| Cerebral Venous Thrombosis (CVT) | Variable presentation. Headache is most common symptom (often severe, progressive, may mimic migraine or IIH). Seizures, focal neurological deficits (related to venous infarcts/hemorrhage), papilledema, altered consciousness possible. Risk factors often present (prothrombotic states, pregnancy/postpartum, oral contraceptives, infection, dehydration, malignancy). | MR Venography (MRV) or CT Venography (CTV) is diagnostic, confirms lack of flow / thrombus ("empty delta sign" on contrast CT/MRI for superior sagittal sinus) in dural sinuses or cortical veins. D-dimer may be elevated but not specific. Brain MRI/CT may show venous infarcts (often hemorrhagic) or edema. |

| Cervicogenic Headache (related to Neck Pain) | Headache referred from a source in the cervical spine (joints, muscles, ligaments, discs). Usually unilateral pain starting in neck/occiput, radiating forward to temporal/frontal/orbital regions. Provoked or aggravated by specific neck movements or sustained awkward neck postures. Reduced cervical range of motion common. Ipsilateral neck/shoulder/arm pain may co-exist. | Clinical diagnosis based on ICHD-3 criteria, requiring evidence of a cervical source linked to headache onset/remission and demonstration of provocation by neck exam. Imaging (X-ray, MRI) may show cervical spine pathology (e.g., arthritis, disc disease) but these findings are common and often non-specific causal links. Diagnostic anesthetic blocks of cervical structures (e.g., C2/3 facet joints, C2/3 nerve roots, greater occipital nerve) can help confirm the diagnosis if they abolish the headache temporarily. |

| Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma | Sudden onset severe unilateral eye pain, often radiating to ipsilateral forehead/temple. Associated blurred vision ("steamy" vision), seeing halos around lights, nausea/vomiting. Eye appears red (conjunctival injection, ciliary flush), cornea may be hazy, pupil often mid-dilated and poorly reactive. | Ophthalmologic emergency. Requires urgent ophthalmology consult. Tonometry shows markedly elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). Gonioscopy confirms closure of the anterior chamber angle. Immediate treatment needed to lower IOP. |

Key elements of the diagnostic process include:

- Detailed Headache History: This is the most critical component. Use the characteristics described earlier (Quality, Location, Intensity, Onset, Duration, Frequency, Timing, Associated Symptoms, Aggravating/Relieving factors - often remembered by mnemonics like PQRST or SOCRATES). Also inquire about past headache history, response to previous treatments, family history of headaches (especially migraine), medication use (including over-the-counter drugs, supplements, caffeine), comorbidities (medical, psychiatric), sleep patterns, and lifestyle factors (stress, diet, exercise). Headache diaries kept prospectively are very valuable for tracking patterns and triggers.

- Neurological Examination: A thorough examination is essential primarily to screen for signs suggestive of a secondary cause ("red flags"). This includes assessment of mental status, cranial nerves (especially visual acuity, visual fields by confrontation, funduscopy for papilledema, pupillary reactions, eye movements), motor function (strength, tone, reflexes), sensation, coordination (finger-nose, heel-shin), and gait.

- Physical Examination: Includes vital signs (BP, temperature), examination of the head and neck for tenderness (palpation of pericranial muscles, sinuses, temporal arteries, TMJ, cervical spine range of motion and tenderness), auscultation for bruits (carotid, orbital), and examination relevant to suspected systemic causes.

- Identifying "Red Flags" (SNOOPP mnemonic is helpful): Certain features suggest a potentially serious underlying cause requiring urgent investigation (usually neuroimaging) [5]:

- Systemic Symptoms (fever, weight loss, chills, myalgias) or Secondary Risk Factors (HIV, cancer, immunosuppression)

- Neurologic Signs or Symptoms (focal deficits like weakness, numbness, diplopia; altered consciousness; papilledema; seizures)

- Onset: Sudden, abrupt, or split-second ("thunderclap" headache)

- Older Age: New onset or progressive headache after age 50 (risk of GCA, tumor, etc.)

- Pattern Change: Significant change in frequency, severity, or clinical features of pre-existing headaches

- Positional Worsening (suggests ICP changes), Precipitated by Valsalva/Exertion, Progressive headache despite treatment.

- Diagnostic Testing (Guided by history and exam findings, especially red flags):

- Neuroimaging: Brain MRI (with/without contrast) is generally preferred for evaluating non-acute headache with red flags due to higher sensitivity for most structural lesions (tumors, inflammation, prior infarcts, Chiari) and lack of radiation. Brain CT (non-contrast) is the first choice in acute/emergency settings to rapidly exclude hemorrhage (SAH, ICH, SDH), hydrocephalus, or large masses. Vascular imaging (MR Angiography/Venography, CT Angiography/Venography) is added if vascular pathology (aneurysm, dissection, vasculitis, CVT) is suspected. Cervical spine MRI may be needed for suspected cervicogenic headache or upper cervical pathology referring pain.

- Lumbar Puncture (LP) for CSF Analysis: Essential if meningitis, encephalitis, or SAH (with negative early CT) is suspected, or sometimes to measure opening pressure (for IIH or low CSF pressure). Must be performed only after neuroimaging has excluded a mass lesion or significant hydrocephalus that could cause herniation. Analysis includes opening pressure, cell count/differential, protein, glucose, Gram stain, cultures, and potentially specific tests (viral PCR, cytology, oligoclonal bands, etc.).

- Blood Tests: Guided by suspicion. Common tests include CBC, ESR, CRP (for infection/inflammation like GCA), basic metabolic panel, thyroid function tests. Specific tests for systemic diseases if indicated.

- Other Tests: Temporal artery biopsy (if GCA suspected). Ophthalmology consult for suspected ocular causes or papilledema. ENT consult for suspected sinus disease. Polysomnography for sleep apnea headache.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated for headache evaluation when clinical features ("red flags") suggest a possible secondary cause, such as structural lesions, vascular abnormalities, or conditions causing abnormal intracranial pressure or hydrocephalus.

Important considerations in headache diagnosis:

- Neuroimaging is generally not required for patients with a long history of stable headaches meeting clear diagnostic criteria for primary headache disorders like typical migraine or typical episodic TTH, especially if the neurological examination is normal [6]. Unnecessary imaging can be costly and may lead to anxiety over incidental findings (e.g., nonspecific white matter spots, pineal cysts) that are usually unrelated to the headache.

- When imaging is indicated for headache evaluation, MRI (without and often with contrast) is generally preferred over CT for most non-acute situations due to its superior ability to detect a wider range of potential underlying pathologies (tumors, inflammation, ischemia, Chiari, pituitary issues, etc.). CT is faster and better for acute hemorrhage and bone detail.

- Surgical procedures targeting supposed "migraine trigger points" (e.g., nerve decompression, muscle resection) are considered controversial and experimental by major headache societies and are generally not recommended as standard practice outside of clinical trials. Evidence-based pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments should be prioritized [7].

- Opioid and barbiturate-containing medications (e.g., codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, butalbital combinations) should generally be avoided or used very sparingly for the routine management of recurring primary headaches (like migraine or TTH) due to high risks of tolerance, dependence, addiction, worsening headache frequency, and development of medication-overuse headache (MOH) [8]. Their use should be limited to rare, specific rescue situations under careful supervision.

- Frequent or prolonged use (e.g., >10-15 days/month depending on class) of any acute headache medication, including simple analgesics (paracetamol/acetaminophen, NSAIDs) and triptans, can lead to Medication-Overuse Headache (MOH), characterized by worsening headache frequency and development of chronic headache. Patients experiencing frequent headaches (>4 per month or debilitating attacks) should consult a physician for an accurate diagnosis and discussion of appropriate preventive strategies, rather than solely relying on escalating acute self-treatment [9].

The Management of Rare Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (TACs)

Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (TACs) are a group of primary headache disorders characterized by severe, strictly unilateral head pain localized in the trigeminal distribution (often orbital, supraorbital, or temporal), accompanied by mandatory ipsilateral cranial autonomic symptoms (such as conjunctival injection, tearing, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, forehead/facial sweating/flushing, miosis, ptosis, sensation of fullness in the ear) [1]. Differentiating between the TACs is crucial as treatment responses vary significantly, with some being exquisitely responsive to specific agents [10].

Key differentiating features based on attack duration, frequency, and response to indomethacin:

TAC Type (ICHD-3) |

Typical Attack Characteristics |

Key Differentiating Feature / Treatment Response |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster Headache (CH) | Duration: 15-180 minutes Frequency: 1 every other day to 8 per day Pain: Excruciating, boring/stabbing, orbital/temporal. Associated restlessness/agitation common during attacks. Autonomic features mandatory. |

Longer duration attacks compared to other TACs (except HC). Often occurs in cyclical "clusters" (episodic CH) or continuously (chronic CH). Responds acutely to high-flow oxygen, subcutaneous/nasal sumatriptan. Preventive options: Verapamil (first-line), lithium, topiramate, galcanezumab. |

| Paroxysmal Hemicrania (PH) | Duration: 2-30 minutes Frequency: Usually ≥5 per day (often very frequent, >10-20/day) Pain: Severe, unilateral orbital/temporal/frontal. Autonomic features mandatory. Less agitation than CH. |

Shorter, very frequent attacks compared to CH. Absolute and rapid response to therapeutic doses of indomethacin is pathognomonic/diagnostic [11]. |

| Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache attacks (SUN) - SUNCT - SUNA |

Duration: 1-600 seconds (often very brief stabs, spikes, or saw-tooth pattern) Frequency: At least 1 attack/day up to hundreds per day (often very frequent bursts). Pain: Moderate/severe, stabbing/burning, orbital/temporal. Autonomic features mandatory. SUNCT: Both conjunctival injection AND tearing prominent. SUNA: Only one or neither of conjunctival injection/tearing. Other autonomic features may be present. |

Very short (seconds), very frequent attacks; often triggered by cutaneous stimuli. Generally refractory to indomethacin and standard CH treatments. Lamotrigine often first-line preventive. Other options: topiramate, gabapentin, IV lidocaine (acute). |

| Hemicrania Continua (HC) | Continuous, moderate-intensity, strictly unilateral background headache present daily for >3 months. Superimposed exacerbations of severe pain occur, during which ipsilateral autonomic features +/- migraine-like features (nausea, photo/phonophobia) are present. | Presence of continuous background unilateral pain. Absolute and rapid response to therapeutic doses of indomethacin is pathognomonic/diagnostic [12]. |

Note: Neuroimaging (MRI Brain) is recommended for all suspected TACs, especially at first presentation, to rule out secondary causes (e.g., pituitary tumors, vascular lesions, posterior fossa pathology) that can mimic TAC phenomenology.

Understanding the presumed pathophysiology involving the trigeminovascular system activation, parasympathetic reflex activation (via the superior salivatory nucleus and sphenopalatine ganglion leading to autonomic symptoms), and potential central modulation/dysfunction (e.g., posterior hypothalamus implicated in cluster headache periodicity) helps guide targeted therapies [13].

Therapeutic approaches targeting different structures/mechanisms in TACs:

Potential Target / Mechanism |

Example Therapy Options (Specific choice depends critically on TAC diagnosis) |

|---|---|

| Acute Attack Abortives | - Oxygen: High-flow (12-15 L/min) 100% oxygen via non-rebreather mask (First-line for Cluster Headache). - Triptans: Subcutaneous or nasal sumatriptan (Effective for Cluster Headache, less so for other TACs). - Lidocaine: Intranasal or IV (May help SUNCT/SUNA acutely). - Indomethacin: Oral or rectal (diagnostic/therapeutic for PH & HC, not effective for CH or SUNCT/SUNA). |

| Preventive Therapy - Channel Modulators | - Verapamil: Calcium channel blocker (First-line preventive for Cluster Headache, requires high doses & ECG monitoring). - Lamotrigine: Sodium channel blocker (Often first-line preventive for SUNCT/SUNA). - Topiramate: Multiple mechanisms including channel modulation (Preventive option for CH, PH, SUNCT/SUNA, HC). - Carbamazepine/Oxcarbazepine: Sodium channel blockers (May help SUNCT/SUNA). - Gabapentin/Pregabalin: Calcium channel modulators (May help SUNCT/SUNA, sometimes CH). |

| Preventive Therapy - Other Pharmacological | - Indomethacin: NSAID (First-line, diagnostic for Paroxysmal Hemicrania & Hemicrania Continua). - Lithium: Mood stabilizer (Preventive option for Cluster Headache, esp. chronic). - Melatonin: May help Cluster Headache prevention. - Corticosteroids: (e.g., Prednisone) Used for short-term transitional therapy to break cluster cycles or induce remission while long-term preventives take effect (CH, sometimes other TACs). |

| Preventive Therapy - Neuromodulation/Interventional | - Greater Occipital Nerve (GON) Block: Injection of local anesthetic +/- steroid (Can provide temporary relief/abort cluster cycles in CH, sometimes helpful in other TACs). - Occipital Nerve Stimulation (ONS): Implanted device (Considered for medically refractory chronic Cluster Headache). - Sphenopalatine Ganglion (SPG) Stimulation: Implanted device (Investigational/approved in some regions for refractory chronic Cluster Headache). - Vagal Nerve Stimulation (VNS): Non-invasive device applied to neck (Approved in some regions for episodic/chronic Cluster Headache). - Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): Targeting posterior hypothalamus (Experimental, for highly refractory chronic Cluster Headache). |

| Preventive Therapy - Biologics | - CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies: (e.g., Galcanezumab approved for episodic Cluster Headache prevention). Erenumab, Fremanezumab studied with variable results in CH. Role in other TACs less clear. |

Note: Choice of therapy must be based on accurate ICHD-3 diagnosis, patient factors, and careful consideration of efficacy and side effects. Indomethacin trial is mandatory if PH or HC is suspected.

Headache and Migraine Treatment

Treatment strategies for headache are highly dependent on the specific diagnosis (primary vs. secondary headache type) and individual patient factors (frequency, severity, duration of attacks, presence of aura, impact on quality of life, comorbidities, patient preferences, previous treatment responses). Accurate diagnosis according to ICHD-3 criteria is paramount before initiating therapy.

General approaches include:

- Acute (Abortive/Rescue) Treatment: Aims to stop or significantly reduce the severity and associated symptoms of a headache attack once it has started. Should be taken as early as possible in the attack for best effect. Examples include:

- Simple Analgesics: Acetaminophen (paracetamol), NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen sodium, diclofenac, aspirin).

- Combination Analgesics: Often contain caffeine, aspirin/acetaminophen +/- butalbital (use limited due to MOH/dependence risk).

- Migraine-Specific Acute Treatments:

- Triptans: Serotonin 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists (sumatriptan, rizatriptan, zolmitriptan, eletriptan, almotriptan, frovatriptan, naratriptan) available in various formulations (oral, nasal spray, injection). First-line for moderate/severe migraine attacks. Contraindicated in uncontrolled hypertension, ischemic heart/vascular disease.

- Gepants: Small molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (ubrogepant, rimegepant for acute treatment). Offer alternative for those who cannot take or do not respond to triptans.

- Ditans: Selective 5-HT1F receptor agonist (lasmiditan). Alternative for acute migraine, lacks vasoconstrictive effects but can cause CNS side effects (dizziness, sedation - driving restrictions).

- Ergots: Dihydroergotamine (DHE - nasal spray, injection), ergotamine tartrate (oral, suppository - use limited by side effects/vasoconstriction).

- Cluster Headache Specific: High-flow Oxygen (100% at 12-15 L/min via non-rebreather mask), subcutaneous or nasal sumatriptan.

- Adjunctive: Antiemetics (metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, ondansetron) for nausea/vomiting, often given with acute treatment.

- Preventive (Prophylactic) Treatment: Aims to reduce the frequency, severity, and/or duration of headache attacks, improve responsiveness to acute treatments, and reduce disability. Considered when attacks are frequent (e.g., ≥4 headache days/month or ≥8 for chronic migraine), severe, prolonged, debilitating, cause significant disability despite optimal acute treatment, or if acute treatments are poorly tolerated/contraindicated/overused. Options vary by headache type and include:

- Migraine Prevention:

- Oral Medications: Beta-blockers (propranolol, metoprolol, timolol), Antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine), Anticonvulsants (topiramate, valproate).

- Injectable Biologics: CGRP monoclonal antibodies (erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, eptinezumab).

- Injectable Neurotoxin: OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox®) for Chronic Migraine only.

- Oral Gepants: Rimegepant, atogepant approved for migraine prevention.

- Other: Candesartan, Lisinopril, certain supplements (magnesium, riboflavin, CoQ10) may have benefit.

- Tension-Type Headache Prevention: Amitriptyline is first-line for chronic TTH. Other options less established (mirtazapine, venlafaxine, topiramate, gabapentin, physical therapy, CBT).

- Cluster Headache Prevention: Verapamil (first-line, requires high dose, ECG monitoring), Lithium (esp. chronic CH), Galcanezumab, Topiramate, Melatonin. Transitional therapy (corticosteroids, GON block).

- Other TACs Prevention: Indomethacin (absolute response defines PH, HC), Lamotrigine (SUNCT/SUNA).

- Migraine Prevention:

- Treatment of Secondary Headaches: Primarily focuses on addressing the underlying cause (e.g., treating infection with antibiotics, managing ICP with medication/shunting, stopping offending medication in MOH, treating sinus disease, managing hypertension, surgical removal of tumor, treating GCA with steroids). Symptomatic headache relief may also be needed concurrently.

- Non-Pharmacological Approaches: Important adjuncts or sometimes primary therapy. Include:

- Lifestyle Modifications: Maintaining regular sleep schedules, regular meals, adequate hydration, regular aerobic exercise, managing stress.

- Identification and Avoidance of Triggers: If specific, consistent triggers are identified (e.g., certain foods, alcohol, sensory stimuli, stress let-down) - though evidence is variable and over-restriction should be avoided.

- Behavioral Therapies: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Biofeedback, Relaxation training (progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery). Strong evidence base, particularly for migraine and TTH.

- Physical Therapies: Exercise, manual therapy (massage, mobilization), posture correction, especially for TTH and cervicogenic headache.

- Acupuncture: Evidence supports efficacy comparable to some pharmacological preventives for migraine and potentially TTH [15].

- Neuromodulation Devices: Various devices targeting trigeminal nerve, vagus nerve, or occipital nerves are available or under investigation (e.g., supraorbital transcutaneous stimulation, non-invasive VNS, single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation).

Management requires individualized treatment plans, realistic expectations, patient education, and regular follow-up to assess efficacy, tolerability, and adjust therapy as needed. Addressing comorbid conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, sleep disorders) is also crucial for optimal headache management.

Specific treatment modalities that might be employed include:

- Pharmacological Therapy (Acute and preventive medications tailored to specific headache diagnosis and patient profile).

- Peripheral Nerve Blocks / Trigger Point Injections (e.g., Greater Occipital Nerve (GON) blocks for occipital neuralgia, cluster headache, migraine; trigger point injections for myofascial pain contributing to tension-type or cervicogenic headache).

- Lumbar Puncture (Primarily diagnostic; therapeutic only in specific circumstances like IIH symptom relief or post-LP headache treatment with epidural blood patch).

- Physiotherapy Modalities (Heat, cold, TENS, ultrasound - often used adjunctively for symptom relief).

- Physical Therapy / Therapeutic Exercise (Essential for cervicogenic headache, helpful for TTH, adjunct for migraine focusing on posture, strength, relaxation).

- Reflexotherapy (Acupuncture) (Evidence supports efficacy for prevention of migraine and tension-type headache).

- Surgical Intervention (Rarely indicated for primary headaches themselves; necessary for certain secondary causes like tumors, aneurysms, Chiari malformation, or refractory trigeminal neuralgia - e.g., microvascular decompression, radiosurgery). Migraine "trigger site" surgery remains controversial.

![]() Attention! While most headaches are benign primary types, sudden severe headaches or headaches with neurological symptoms ("red flags") require immediate medical evaluation to rule out serious underlying causes. Self-treating frequent or severe headaches without a proper diagnosis can be ineffective and potentially delay treatment for a serious condition or lead to medication-overuse headache. Consult a healthcare professional for accurate diagnosis and management.

Attention! While most headaches are benign primary types, sudden severe headaches or headaches with neurological symptoms ("red flags") require immediate medical evaluation to rule out serious underlying causes. Self-treating frequent or severe headaches without a proper diagnosis can be ineffective and potentially delay treatment for a serious condition or lead to medication-overuse headache. Consult a healthcare professional for accurate diagnosis and management.

References

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018 Jan;38(1):1-211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202

- Ray BS, Wolff HG. Experimental studies on headache; pain-sensitive structures of the head and their significance in headache. Arch Surg. 1940;41(4):813–57. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1940.01210040002001

- Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, Hoffmann J, Schankin C, Akerman S. Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing. Physiol Rev. 2017 Apr;97(2):553-622. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2015

- Dodick DW. Diagnosing headache: a crucial step toward effective treatment. Postgrad Med. 2000;107(4):33-4, 37-40. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2000.04.1023

- Dodick DW. Clinical Practice. Chronic daily headache. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jan 12;354(2):158-65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp052855

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Headache. Revised 2019. Available from: https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69483/Narrative/

- American Headache Society Position Statement on Surgical Decompression of Migraine Headache Trigger Sites. Headache. 2020;60(8):1740-1742. doi: 10.1111/head.13968

- American Headache Society Consensus Statement: Integrating New Migraine Treatments Into Clinical Practice. Headache. 2019 Jan;59(1):1-18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456

- Diener HC, et al. Medication-overuse headache: a worldwide problem. Lancet Neurol. 2004 Nov;3(11):725-7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00932-3

- Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB. A review of paroxysmal hemicranias, SUNCT syndrome and other short-lasting headaches with autonomic feature, including new cases. Brain. 1997 Jan;120 ( Pt 1):193-209. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.1.193

- Antonaci F, Sjaastad O. Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (CPH): a review of the clinical manifestations. Headache. 1989 Nov;29(10):648-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1989.hed2910648.x

- Cittadini E, Goadsby PJ. Hemicrania continua: a clinical study of 39 patients with diagnostic implications. Brain. 2010 Jul;133(7):1973-86. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq138

- Goadsby PJ. Pathophysiology of cluster headache: a trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia. Lancet Neurol. 2002 Aug;1(4):251-7. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00068-6

- Wei DY, Yuan Ong JJ, Goadsby PJ. Cluster Headache: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2018;21(Suppl 1):S3-S8. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_349_17

- Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jun 28;(6):CD001218. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub3

- Chaibi A, Russell MB. Manual therapies for primary chronic headaches: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:67. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-67

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)