Encephalopathy

Encephalopathy Overview

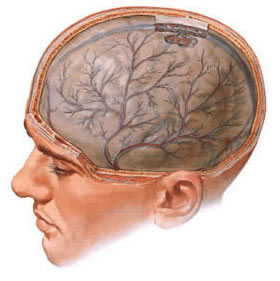

Encephalopathy is a broad term describing any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure [1]. It manifests as a global cerebral dysfunction, often characterized by altered mental status (ranging from confusion and delirium to coma), cognitive impairment, personality changes, and sometimes motor or sensory deficits like asterixis or myoclonus. Underlying causes can lead to degenerative changes in brain tissue, potentially resulting in reduced brain volume (atrophy) and impaired neurological function over time.

Encephalopathy is not a single disease but rather a syndrome resulting from various underlying conditions. Common causes include:

- Vascular Encephalopathy: Caused by impaired blood flow to the brain.

- Atherosclerosis: Narrowing of cerebral arteries due to plaque buildup, reducing blood flow (contributing to chronic vascular encephalopathy).

- Chronic Hypertension: Long-term high blood pressure damages small blood vessels (leading to lacunar infarcts, white matter disease). Hypertensive encephalopathy is an acute manifestation.

- Vascular Discirculation / Small Vessel Disease: General term for poor circulation, often related to diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia.

- Chronic Cerebral Ischemia: Persistent reduced oxygen supply to the brain due to widespread vascular disease.

- Metabolic/Systemic Encephalopathy: Resulting from systemic illness or metabolic imbalances [2].

- Hepatic Encephalopathy: Liver failure leads to accumulation of toxins (like ammonia) affecting the brain.

- Uremic Encephalopathy: Kidney failure causes buildup of uremic toxins.

- Diabetic Encephalopathy: Related to complications of diabetes mellitus, including severe hyperglycemia (hyperosmolar state) or hypoglycemia.

- Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy: Brain damage due to lack of oxygen (e.g., after cardiac arrest, drowning, asphyxia).

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Severe disturbances in sodium (hyponatremia, hypernatremia), calcium, magnesium, phosphate.

- Endocrine Disorders: Thyroid dysfunction (myxedema coma, thyrotoxic crisis), adrenal insufficiency (Addisonian crisis).

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Thiamine deficiency (Wernicke's encephalopathy).

- Infectious/Inflammatory Encephalopathy:

- Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy: Diffuse brain dysfunction related to systemic inflammatory response in sepsis.

- Viral Encephalitis (though often termed encephalitis, severe cases lead to diffuse dysfunction qualifying as encephalopathy).

- Autoimmune Encephalopathy (e.g., Hashimoto's encephalopathy, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis).

- Toxic Encephalopathy: Exposure to poisons or drugs.

- Alcohol-Related (acute intoxication, withdrawal delirium tremens, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome).

- Drug Overdose (sedatives, opioids, etc.) or Side Effects (e.g., anticholinergics).

- Heavy Metals (lead, mercury, manganese), Solvents, Pesticides, Carbon Monoxide.

- Traumatic Encephalopathy:

- Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE): Progressive tauopathy associated with repetitive head trauma (often seen in contact sport athletes, military personnel) [3].

- Acute Post-Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Global dysfunction immediately following severe TBI.

- Other Causes:

- Radiotherapy (Radiation Encephalopathy).

- Mitochondrial Diseases (e.g., MELAS).

- Prion Diseases (e.g., Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease).

- Increased Intracranial Pressure (e.g., due to large tumor, hydrocephalus, venous sinus thrombosis).

Encephalopathy Types

Encephalopathies are broadly categorized based on their underlying cause or specific clinical/pathological features. Some prominent types include:

- Metabolic Encephalopathies: Hepatic, Uremic, Hypoglycemic, Hyperglycemic (Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State - HHS, Diabetic Ketoacidosis - DKA), Hypoxic-Ischemic, Electrolyte-related (Na+, Ca++, Mg++, Phosphate), Endocrine (Thyroid, Adrenal), Nutritional (Wernicke's).

- Toxic Encephalopathies: Alcohol-related (intoxication, withdrawal, Wernicke-Korsakoff), Drug-induced (sedatives, opioids, lithium, anticholinergics, chemotherapeutics), Heavy metal poisoning (Lead, Mercury, Manganese, Arsenic), Organic solvents, Carbon Monoxide.

- Infectious/Inflammatory Encephalopathies: Sepsis-associated encephalopathy, Viral (e.g., HIV encephalopathy, post-viral syndromes), Prion diseases (Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease - CJD), Autoimmune (Hashimoto's encephalopathy, Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, Limbic encephalitis).

- Traumatic Encephalopathies: Acute post-TBI encephalopathy, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

- Vascular Encephalopathies:

- Chronic Vascular Encephalopathy / Vascular Cognitive Impairment (often related to small vessel disease, atherosclerosis, multiple lacunar infarcts).

- Subcortical Ischemic Vascular Disease (Binswanger's disease).

- Hypertensive Encephalopathy / Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES).

- CADASIL (Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy).

- Other Specific Types:

- Radiation Encephalopathy (acute, early-delayed, late-delayed).

- Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy with Lactic Acidosis and Stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome.

- Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML - caused by JC virus reactivation in immunocompromised individuals).

- Neonatal Encephalopathy (often hypoxic-ischemic).

Hypertensive Encephalopathy

Hypertensive encephalopathy (HE) is an acute neurological syndrome caused by a sudden, severe elevation in blood pressure that overwhelms the brain's cerebrovascular autoregulatory capacity. This leads to breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, resulting in vasogenic edema (fluid leakage into the interstitial space of the brain), and potentially microhemorrhages or petechiae [5]. It typically occurs with markedly elevated blood pressure (e.g., mean arterial pressure >150 mmHg or diastolic >120-130 mmHg), often in the context of malignant hypertension or rapid rises in blood pressure.

Clinical presentation is characterized by the relatively rapid onset (hours to days) of neurological symptoms, including:

- Severe, diffuse headache (often described as throbbing).

- Altered mental status: Confusion, agitation, restlessness, irritability, lethargy, progressing to stupor or coma if untreated.

- Visual disturbances: Blurred vision, scotomata, cortical blindness, hemianopia. These are often associated with papilledema (optic disc swelling) seen on funduscopy.

- Seizures: Generalized tonic-clonic seizures are common.

- Nausea and vomiting (often related to increased intracranial pressure).

- Focal neurological signs: Less common than diffuse symptoms, but transient hemiparesis, aphasia, or ataxia can occur, potentially mimicking stroke (hemorrhage, embolism, or thrombosis).

The underlying hypertension may be essential (primary) or secondary to conditions like chronic kidney disease, acute glomerulonephritis, renal artery stenosis, preeclampsia/eclampsia, pheochromocytoma, Cushing’s syndrome, connective tissue diseases (like scleroderma), or abrupt withdrawal from antihypertensive medications (e.g., clonidine). Examination reveals markedly elevated blood pressure and often signs of end-organ damage, particularly grade III or IV hypertensive retinopathy (retinal hemorrhages, flame hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, papilledema).

Lumbar puncture (LP), if performed (use cautiously due to risk of herniation if significant edema/mass effect is present), often shows elevated opening pressure and increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein content (sometimes exceeding 1 g/L or 100 mg/dL, reflecting blood-brain barrier breakdown), with usually normal or near-normal cell counts and glucose [1]. (Note: CSF protein reference range typically up to ~45 mg/dL or 0.45 g/L).

Neuroimaging, particularly MRI, typically shows characteristic bilateral, often symmetric vasogenic edema (T2/FLAIR hyperintensity) predominantly affecting the white matter of the posterior cerebral regions (parietal, occipital lobes), but also potentially involving the brainstem, cerebellum, basal ganglia, and frontal lobes – a pattern now widely recognized as **Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES)** [6, 7]. Prompt and controlled reduction of blood pressure (typically lowering mean arterial pressure by 10-20% in the first hour, then gradually further towards target over 24-48 hours) with appropriate intravenous antihypertensive medications (e.g., labetalol, nicardipine, clevidipine) is the cornerstone of treatment and usually leads to reversal of neurological symptoms and imaging findings within days to weeks. Failure to control hypertension promptly can lead to irreversible brain damage (infarction, hemorrhage), coma, and death.

Postmortem studies in historical fatal cases often revealed cerebral edema, petechial hemorrhages, fibrinoid necrosis of arterioles, and sometimes larger intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhages. Signs of herniation (e.g., cerebellar tonsillar herniation through the foramen magnum) might be present due to increased brain volume from severe edema.

It is important to differentiate hypertensive encephalopathy/PRES from other conditions associated with hypertension, such as chronic headaches, chronic dizziness related to vertebral-basilar insufficiency (VBI), hypertensive strokes (ischemic or hemorrhagic), or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). Hypertensive encephalopathy specifically refers to the acute syndrome of neurological dysfunction directly caused by severely elevated blood pressure and typically reversed by lowering it.

Encephalopathy Diagnosis

Diagnosing encephalopathy involves recognizing the characteristic clinical syndrome of diffuse brain dysfunction and systematically determining its underlying cause. The diagnostic process typically includes:

Differential Diagnosis of Encephalopathy / Altered Mental Status

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Encephalopathy (Hepatic, Uremic, Hypoglycemic, Electrolyte, etc.) | Fluctuating consciousness, confusion, delirium, inattention. Often global neurological signs (asterixis, myoclonus). Identifiable underlying systemic illness/metabolic derangement. Usually symmetric findings. | Specific lab abnormalities (Ammonia, BUN/Cr, Glucose, Lytes, LFTs, TSH). EEG often shows diffuse slowing +/- triphasic waves (hepatic, uremic). Imaging usually non-specific initially but may show basal ganglia changes (hepatic). |

| Toxic Encephalopathy (Drugs, Alcohol, Toxins) | Altered mental status, confusion, ataxia, slurred speech, nystagmus. History of exposure/ingestion crucial. Specific toxidrome may be present (e.g., pupillary changes, vital sign abnormalities). | Toxicology screen positive. Blood alcohol level. Specific toxin levels if suspected (e.g., COHb, heavy metals). Clinical signs of intoxication/withdrawal. Brain MRI may show specific patterns (e.g., Wernicke's). |

| Infectious (Meningitis, Encephalitis, Sepsis) | Fever, headache, neck stiffness (meningismus), altered mental status. Focal signs/seizures more common with encephalitis. Signs of systemic infection in sepsis (hypotension, tachycardia). | LP shows CSF pleocytosis, altered protein/glucose (if safe to perform). MRI may show meningeal enhancement or parenchymal changes (encephalitis - e.g., temporal lobes in HSE). Blood cultures (sepsis). Inflammatory markers elevated. |

| Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy | History of cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, severe hypotension, CO poisoning. Diffuse brain dysfunction, coma, seizures, postanoxic myoclonus common. | MRI shows characteristic pattern of injury (watershed cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum). History of hypoxic event critical. EEG shows diffuse slowing, burst suppression, or seizures. |

| Hypertensive Encephalopathy / PRES | Acute onset with severely elevated BP. Headache, confusion, visual changes, seizures. | Markedly elevated BP. Funduscopy shows hypertensive retinopathy/papilledema. MRI shows characteristic posterior white matter vasogenic edema (PRES). Symptoms improve rapidly with BP control. |

| Stroke (Large Ischemic/Hemorrhagic) | Sudden onset of *focal* neurological deficits usually predominates. Altered mental status more common with large territory strokes, brainstem strokes, or significant hemorrhage/edema. | CT/MRI confirms stroke type and location. Focal neurological signs correlate with vascular territory. MRA/CTA may show vessel occlusion/stenosis. |

| Seizure (Non-convulsive status epilepticus or Prolonged Post-ictal state) | Persistent confusion/altered awareness after a known seizure (post-ictal, usually resolves <24-48h). Or ongoing altered mental status without clear convulsions (NCSE - diagnosis of exclusion). | EEG is diagnostic, showing seizure activity (NCSE) or post-ictal slowing. Response to IV anti-epileptic drugs may be diagnostic/therapeutic for NCSE. |

| Intracranial Hemorrhage (SDH, SAH, ICH) | Can present with altered mental status, headache, focal deficits depending on type/location/size. History of trauma (SDH, ICH) or sudden severe "thunderclap" headache (SAH). | Head CT scan is primary diagnostic tool for acute hemorrhage. MRI provides more detail later. LP may show blood/xanthochromia in SAH if CT negative. |

| Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) | Clear history of significant head trauma usually present. Range of symptoms from confusion to coma. | CT/MRI shows traumatic lesions (contusion, hematoma, fracture, diffuse axonal injury). GCS score quantifies acute severity. |

| Delirium Superimposed on Dementia | Dementia: Chronic, progressive cognitive decline baseline. Delirium: Acute, fluctuating disturbance of attention and awareness, often triggered by underlying illness (UTI, pneumonia), medication change, or hospitalization in vulnerable patients (elderly, demented). | Clinical history & cognitive assessment (e.g., CAM assessment for delirium) key. Need to identify and treat underlying trigger for delirium. Brain imaging may show atrophy (dementia) or be normal/non-specific for delirium. |

| Brain Tumor (Large or Multifocal) | Subacute/progressive headache, focal deficits, seizures, cognitive/personality changes depending on location/size/type. Can cause raised ICP. | MRI with contrast is diagnostic, showing mass lesion(s) +/- edema. Biopsy confirms histology. |

| Autoimmune/Paraneoplastic Encephalopathy | Subacute onset cognitive changes, psychiatric symptoms, seizures, movement disorders. May have history of cancer (paraneoplastic) or autoimmune disease. | MRI may show limbic encephalitis (temporal lobe T2/FLAIR signal). CSF may show mild pleocytosis/protein elevation. Specific autoantibody testing (serum/CSF) is key (e.g., anti-NMDA, LGI1, GAD65, Hu, Yo, Ri). PET scan for occult malignancy. |

Neuroimaging techniques like Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) play a crucial role in evaluating suspected encephalopathy, helping to identify structural changes, edema, ischemia, inflammation, or specific patterns associated with various causes.

Diagnosing encephalopathy involves identifying the characteristic clinical syndrome of diffuse brain dysfunction and determining its underlying cause. The diagnostic process typically includes:

- Clinical History and Examination: Gathering detailed information about the onset and progression of symptoms (altered mental status, memory problems, personality changes, headaches, dizziness, seizures, motor deficits), potential exposures (toxins, drugs, alcohol), underlying medical conditions (liver, kidney, heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, infections, autoimmune disorders), recent trauma, or family history. A thorough neurological examination assesses mental status (orientation, attention via tasks like serial 7s or months backwards, memory recall, executive function), cranial nerves, motor system (tone, strength, reflexes, presence of asterixis or myoclonus), sensory systems, coordination, and gait.

- Laboratory Investigations: Blood tests are essential to identify metabolic, toxic, infectious, or systemic causes. Key tests often include:

- Complete blood count (CBC with differential)

- Comprehensive metabolic panel (Electrolytes - sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, calcium, magnesium, phosphate; Glucose; Renal function tests - BUN, creatinine; Liver function tests - bilirubin, transaminases, albumin, PT/INR)

- Ammonia level (if hepatic encephalopathy suspected)

- Thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4)

- Vitamin levels (especially B1/thiamine if Wernicke's suspected, B12)

- Arterial blood gas (ABG - for oxygenation, ventilation PaCO2, and acid-base status)

- Toxicology screen (urine and/or serum for drugs of abuse, specific drug levels like acetaminophen, salicylates, anticonvulsants if relevant)

- Blood alcohol level

- Infectious workup (blood cultures, inflammatory markers like C-Reactive Protein (CRP)/Procalcitonin, urinalysis, chest X-ray, specific serologies if indicated like HIV)

- Autoimmune markers (ANA, specific neuronal antibodies if autoimmune encephalitis suspected).

- Consider Creatine Kinase (CK) for rhabdomyolysis, lactate for tissue hypoperfusion/mitochondrial disease.

- Neuroimaging:

- Brain MRI (with and without contrast, including DWI/ADC): Often the preferred imaging modality as it provides detailed anatomical information and is sensitive to changes like edema (vasogenic vs. cytotoxic), inflammation, ischemia, atrophy, white matter changes (leukoencephalopathy), microhemorrhages (using susceptibility-weighted sequences like SWI/GRE), or specific patterns seen in certain encephalopathies (e.g., PRES, Wernicke's, CJD, hepatic, hypoxic-ischemic, MELAS).

- Brain CT (non-contrast): Useful primarily in acute settings to rapidly exclude significant intracranial hemorrhage, large tumors, hydrocephalus, or obvious stroke. Less sensitive than MRI for subtle parenchymal changes typical of many metabolic, toxic, or inflammatory encephalopathies. Contrast may be added if mass/infection suspected.

- MR Angiography (MRA) or CT Angiography (CTA): Evaluate cerebral vasculature if a primary vascular cause (e.g., vasculitis, dissection, large vessel occlusion) is suspected.

- Electroencephalography (EEG): Measures brain electrical activity. Very useful in assessing diffuse cerebral dysfunction. Often shows background slowing (theta/delta activity) proportionate to the severity of encephalopathy. Can help detect non-convulsive seizures (which can present as unexplained altered mental status), assess prognosis (e.g., after hypoxia), and sometimes show specific patterns suggestive of certain etiologies (e.g., triphasic waves in moderate-severe metabolic/hepatic encephalopathy; periodic discharges in CJD or anoxia).

- Lumbar Puncture (LP) for CSF Analysis: Crucial if infection (meningitis, encephalitis) or specific inflammatory/autoimmune conditions (e.g., autoimmune encephalitis, paraneoplastic syndromes) are suspected, *provided neuroimaging has excluded significantly raised ICP or mass effect that would make LP unsafe*. CSF is analyzed for opening pressure, cell count and differential, protein, glucose, Gram stain and cultures (bacterial, fungal, AFB), viral PCRs (e.g., HSV, VZV), cytology (for malignancy), specific proteins (e.g., 14-3-3 for CJD), oligoclonal bands/IgG index (for inflammation), and specific autoantibodies if indicated.

- Other Tests: Depending on clinical suspicion, tests like Doppler ultrasonography of cerebral vessels, echocardiogram (for cardioembolic sources or endocarditis), specific genetic testing (e.g., for mitochondrial diseases, CADASIL), heavy metal testing, or neuropsychological testing (to formally quantify cognitive deficits, especially in chronic cases) may be indicated.

Common clinical manifestations observed during examination include apathy, psychomotor slowing or agitation, disorientation (time, place, person), memory impairment (especially recent memory), reduced attention span/distractibility, slurred speech (dysarthria), impaired judgment, emotional lability (irritability, tearfulness, apathy), sleep-wake cycle disturbances, and sometimes abnormal movements (asterixis - "flapping tremor", myoclonus, tremor), gait abnormalities, or motor deficits.

Vascular causes of encephalopathy, sometimes termed dyscirculatory or vascular cognitive impairment, can be evaluated using techniques like computed tomography (CT) angiography to visualize cerebral blood vessels for stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysms.

Encephalopathy Treatment

The treatment of encephalopathy is fundamentally directed at **identifying and managing the underlying cause**. Specific therapies vary widely depending on the etiology [8]. General principles include supportive care and addressing the primary condition:

- Addressing the Underlying Cause: This is the most crucial step and dictates specific treatment. Examples include:

- Metabolic: Correcting electrolyte imbalances (e.g., slow correction of severe hyponatremia), managing blood glucose (treating hypoglycemia emergently, managing DKA/HHS), treating liver failure (e.g., lactulose and rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy), dialysis for severe uremic encephalopathy, prompt reoxygenation/reperfusion for hypoxic-ischemic injury, thiamine replacement *before* glucose for suspected Wernicke's.

- Toxic: Stopping exposure, enhancing elimination (e.g., activated charcoal, dialysis), administering specific antidotes if available (e.g., naloxone for opioids, fomepizole for methanol/ethylene glycol).

- Infectious: Appropriate antimicrobial therapy (antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals) based on likely/confirmed pathogen.

- Hypertensive (HE/PRES): Controlled, prompt lowering of blood pressure using intravenous agents.

- Autoimmune: Immunosuppressive therapy (high-dose corticosteroids, IVIg, plasma exchange, rituximab, cyclophosphamide depending on specific diagnosis).

- Vascular: Managing vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia), antiplatelet agents if appropriate (for chronic ischemic disease, not typically for acute PRES), anticoagulation for venous thrombosis.

- Nutritional: Correcting deficiencies (e.g., thiamine, B12).

- Supportive Care: Critical for managing acutely ill patients. This includes:

- Maintaining airway patency (intubation if necessary), ensuring adequate breathing and oxygenation, and supporting circulation (managing blood pressure).

- Ensuring adequate nutrition and hydration (often via NG tube or IV fluids initially).

- Preventing complications like aspiration pneumonia, pressure ulcers, deep vein thrombosis (DVT prophylaxis), and stress ulcers.

- Managing agitation safely (often with non-pharmacological measures first, then short-acting sedatives like lorazepam or antipsychotics like haloperidol if needed, avoiding agents that worsen confusion like benzodiazepines long-term).

- Environmental modifications to reduce delirium (reorientation, minimizing stimuli at night, encouraging mobility).

- Symptomatic Treatment: Medications may be used to manage specific symptoms like seizures (antiepileptics), myoclonus, or severe agitation, but the primary treatment should always focus on reversing the underlying cause. Cognitive enhancers (e.g., cholinesterase inhibitors) have limited proven efficacy in most encephalopathies except potentially specific dementias.

- Rehabilitation: For patients with residual cognitive, motor, or functional deficits after the acute phase resolves, comprehensive rehabilitation involving physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy (including cognitive-linguistic therapy), and neuropsychological rehabilitation is often essential for maximizing recovery.

Chronic encephalopathies, particularly neurodegenerative or progressive vascular types, often require long-term management focusing on slowing progression where possible (e.g., strict vascular risk factor control), managing symptoms (cognitive, behavioral, motor), providing caregiver support, and maximizing patient function and quality of life. This may involve regular follow-up and potentially periodic intensive therapy courses.

Specific therapeutic modalities that might be employed depending on the type and symptoms of encephalopathy include:

- Drug Therapy: Including medications targeting the underlying cause (see above), controlling symptoms (e.g., anti-seizure drugs like levetiracetam, valproate), potentially attempting to improve cognition (nootropics - efficacy often debated/limited), managing vascular risk factors (statins, antihypertensives), vitamin supplementation (thiamine, B12).

- Epidural Injections: Generally not indicated for encephalopathy itself, but might be used for unrelated associated spinal pain syndromes.

- Lumbar Puncture: Primarily diagnostic, but large volume LP can temporarily relieve symptoms in normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), which presents with cognitive impairment, gait disturbance, and incontinence and can sometimes be considered in the differential of chronic encephalopathy in the elderly.

- Physical Therapy Modalities: Heat, cold, ultrasound, electrical stimulation (TENS) used as adjuncts for pain or muscle issues.

- Therapeutic Exercise (Physical Therapy): Crucial component of rehabilitation for maintaining mobility, strength, balance, and function, preventing complications of immobility.

- Reflexotherapy (Acupuncture): May be used by some patients as a complementary therapy for symptom management (e.g., pain, nausea, fatigue), though high-quality evidence for efficacy in encephalopathy itself is generally lacking.

- Surgical Treatment: Rarely indicated for encephalopathy itself, but may be necessary for treating specific underlying causes (e.g., tumor removal, CSF shunting for hydrocephalus causing chronic symptoms, carotid endarterectomy/stenting for severe carotid stenosis potentially contributing to vascular encephalopathy, liver transplant for hepatic encephalopathy).

Acupuncture is sometimes explored as a complementary therapy for managing symptoms such as pain or fatigue that can accompany certain types of encephalopathy.

![]() Attention! Encephalopathy, particularly if acute in onset, represents a serious medical condition requiring prompt evaluation to determine the underlying cause. Changes in mental status, severe headaches, seizures, or rapid neurological decline warrant immediate medical attention. Diagnosis and treatment require expert medical assessment, often involving neurologists and specialists in related fields (e.g., hepatology, nephrology, infectious disease). Self-diagnosis is dangerous.

Attention! Encephalopathy, particularly if acute in onset, represents a serious medical condition requiring prompt evaluation to determine the underlying cause. Changes in mental status, severe headaches, seizures, or rapid neurological decline warrant immediate medical attention. Diagnosis and treatment require expert medical assessment, often involving neurologists and specialists in related fields (e.g., hepatology, nephrology, infectious disease). Self-diagnosis is dangerous.

References

- Chapter 5: Confusion, Delirium, and Acute Encephalopathy. In: Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Plum F, Posner JB. The Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma. 3rd ed. FA Davis; 1980.

- McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009 Jul;68(7):709-35. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503

- Pavlakis SG, Phillips PC, DiMauro S, De Vivo DC, Rowland LP. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: a distinctive clinical syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1984;16(4):481-8. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160409

- Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Hypertensive emergencies. Lancet. 2000;356(9227):411-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02539-3

- Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):494-500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602223340803

- Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Sep;14(9):914-25. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00111-8

- Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, Plum F. Plum and Posner's Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2007.

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)