Vertebro-basilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

VBI and Vertigo: Overview

Vertigo is the sensation of spinning or rotation – either of oneself or the surroundings – often accompanied by a disturbance in spatial orientation [1]. It is a common symptom encountered in medical practice.

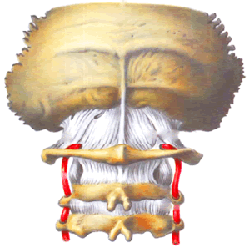

Vertebro-Basilar Insufficiency (VBI) refers to reduced blood flow within the vertebral and basilar arteries, the vessels supplying the posterior part of the brain (brainstem, cerebellum, occipital lobes) [2]. VBI can cause various neurological symptoms due to transient or permanent ischemia in this territory [2].

While vertigo is a frequent symptom associated with VBI, it is crucial to understand that isolated vertigo (vertigo as the only symptom) is RARELY caused by VBI [1, 2]. When vertigo results from ischemia in the vertebrobasilar system (a central cause), it is almost always accompanied by other signs of brainstem or cerebellar dysfunction [1, 2].

Patients experiencing VBI may present with a constellation of symptoms, often described in various ways: "dizziness," "lightheadedness," "unsteadiness," "spinning," potentially associated with nausea, vomiting, weakness, visual changes, headache, or changes in blood pressure [1].

Causes of Vertigo in VBI

Vertigo in the context of VBI arises from ischemia affecting the vestibular nuclei in the brainstem or their connections with the cerebellum and inner ear pathways, all supplied by the vertebrobasilar system [1, 2].

The underlying causes of VBI leading to such ischemia include [2, 3]:

- Atherosclerosis: Narrowing or blockage of the vertebral or basilar arteries due to plaque buildup is a common cause, particularly in older adults.

- Arterial Dissection: A tear in the wall of a vertebral artery, often occurring spontaneously or after minor neck trauma/manipulation, especially in younger individuals.

- Embolism: Clots traveling from the heart or proximal arteries lodging in the vertebrobasilar system.

- Subclavian Steal Syndrome: Reversal of blood flow in the vertebral artery due to severe stenosis or occlusion of the subclavian artery proximal to the VA origin, sometimes triggered by arm exercise.

- Less Common Causes: Vasculitis, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), external compression (rarely, by cervical osteophytes or tumors).

While cervical spondylosis (osteoarthritis/osteochondrosis) is common, its role in directly causing VBI solely through reflex spasm is debatable and likely less significant than structural causes like stenosis or dissection [1]. However, severe degenerative changes can potentially contribute to VBI by causing dynamic compression of the vertebral artery during certain neck movements or predisposing to dissection [1].

It's important to differentiate VBI-related vertigo from other common causes of vertigo, which are often peripheral (inner ear related) [1]:

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

- Vestibular Neuritis / Labyrinthitis

- Meniere's Disease

- Other potential central causes not directly related to VBI: Multiple sclerosis, acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma), cerebellar tumors, migraine-associated vertigo, intoxication, head injury.

Differentiating Central vs. Peripheral Vertigo

Distinguishing vertigo originating from the central nervous system (CNS - brainstem/cerebellum, as in VBI) from vertigo originating in the peripheral vestibular system (inner ear) is critical [1, 5]. The following table summarizes key differentiating features [1, 5]:

| Sign or Symptom | Manifestation in Central Vertigo (e.g., VBI) | Manifestation in Peripheral Vertigo (e.g., BPPV, Vestibular Neuritis) |

|---|---|---|

| Associated Neurological Symptoms | Commonly PRESENT (e.g., diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, limb weakness/numbness, ataxia disproportionate to vertigo) | Typically ABSENT (May have hearing loss/tinnitus with specific inner ear conditions) |

| Nystagmus | Often vertical, purely torsional, or direction-changing gaze-evoked; May not suppress with visual fixation. | Usually horizontal or mixed horizontal-torsional; Unidirectional (fast phase away from affected ear); Suppresses with visual fixation. |

| Severity of Vertigo | Often less intense, more constant sense of imbalance. | Can be very intense, often episodic or positional. |

| Nausea/Vomiting | Variable. | Often severe, especially acutely. |

| Ataxia / Gait Imbalance | Often severe, patient may be unable to stand or walk. | Present, but patient often still able to stand/walk with support (unless very acute/severe). |

| Positional Testing (e.g., Dix-Hallpike) | Nystagmus may persist, not fatigue, have no latency, or be atypical (e.g., vertical). | Classic BPPV: Latency (few seconds), fatigues with repetition, characteristic torsional-upbeating nystagmus. |

| Hearing Loss / Tinnitus | Usually absent (unless AICA territory stroke). | May be present (e.g., Meniere's disease, labyrinthitis). |

The HINTS exam (Head Impulse, Nystagmus, Test of Skew) is a valuable bedside tool for acutely differentiating central (stroke) from peripheral causes in patients with continuous vertigo and nystagmus [5].

Diagnosing Vertigo and VBI

Diagnosing VBI as the cause of vertigo requires demonstrating evidence of posterior circulation ischemia or the underlying vascular pathology, typically in the presence of accompanying neurological symptoms [1, 2].

The diagnostic process includes [1, 2, 4]:

- Detailed History: Characterizing the vertigo (timing, duration, triggers, severity), and crucially, inquiring about associated symptoms like double vision (diplopia), slurred speech (dysarthria), swallowing difficulty (dysphagia), weakness or numbness (especially bilateral or alternating), clumsiness (ataxia), visual field loss, or drop attacks (sudden falls without loss of consciousness). History of vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation) is essential.

- Neurological Examination: A thorough exam focusing on cranial nerves (eye movements, facial sensation/movement, hearing, palate/tongue function), motor strength, sensation, coordination (cerebellar testing), gait, and reflexes. Specific tests like the HINTS exam may be performed if applicable.

- Vascular Imaging: To assess the vertebral and basilar arteries for stenosis, occlusion, or dissection.

- Carotid and Vertebral Artery Doppler Ultrasound: Non-invasive screening for extracranial VA stenosis or abnormal flow patterns (e.g., suggesting subclavian steal or distal occlusion).

- CT Angiography (CTA) Head and Neck: Provides detailed images of arteries from the aortic arch through the Circle of Willis. Good for detecting stenosis, occlusion, dissection.

- MR Angiography (MRA) Head and Neck: Alternative non-invasive imaging, particularly useful for detecting dissection when combined with vessel wall imaging sequences.

- Brain Imaging:

- MRI Brain: Essential to look for evidence of acute or chronic ischemic stroke in the brainstem, cerebellum, thalamus, or occipital lobes. DWI sequences are critical for detecting acute ischemia. Also helps rule out other central causes (tumor, MS plaques).

- CT Brain: Primarily used initially to exclude hemorrhage, less sensitive for posterior fossa ischemia.

- Other Tests (as indicated): ECG (for atrial fibrillation), Holter monitoring, Echocardiography (to rule out cardioembolic source), blood tests (glucose, lipids, hematology). (Rheoencephalography [REG] is an outdated technique with limited diagnostic value for VBI).

Differential Diagnosis of Vertigo [1, 5, 6]

| Category | Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Vestibular (Inner Ear / Vestibular Nerve) |

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) | Brief episodes (seconds) triggered by specific head movements (e.g., rolling over in bed). No hearing loss. Positive Dix-Hallpike test. |

| Vestibular Neuritis | Acute onset, severe continuous vertigo lasting days, nausea/vomiting, gait instability. NO hearing loss. Often post-viral. Abnormal head impulse test. | |

| Labyrinthitis | Similar to vestibular neuritis BUT includes hearing loss and/or tinnitus. Often post-viral or otitis media complication. | |

| Meniere's Disease | Episodic vertigo (minutes to hours) accompanied by fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and ear fullness. | |

| Central Vestibular (Brainstem / Cerebellum) |

Vertebrobasilar Ischemia (TIA/Stroke) | Vertigo ALMOST ALWAYS accompanied by other CNS symptoms (diplopia, dysarthria, weakness, numbness, ataxia). Sudden onset. Risk factors present. Abnormal HINTS exam possible. |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | Acute/subacute onset vertigo, often with other neurological signs (e.g., INO, ataxia, sensory changes). History of prior episodes possible. | |

| Cerebellar Tumor / Stroke | Vertigo, prominent ataxia/gait instability often out of proportion to vertigo severity. Headache, nausea/vomiting common. May have signs of increased ICP if large. | |

| Vestibular Migraine (Migraine-associated Vertigo) | Episodic vertigo (minutes to days), often associated with headache (but can occur without), photophobia, phonophobia. History of migraine common. | |

| Brainstem Tumor | Progressive vertigo/dizziness, often with multiple cranial nerve palsies and long tract signs. | |

| Other | Medication Side Effect | Many drugs can cause dizziness/vertigo (e.g., anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, aminoglycosides, sedatives). Related to drug initiation/dose change. |

| Anxiety / Panic Disorder / PPPD | Feeling of dizziness/lightheadedness/unsteadiness, often situational. Associated anxiety symptoms. PPPD: Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. | |

| Systemic Causes (e.g., Hypotension, Hypoglycemia, Anemia) | Usually causes lightheadedness or presyncope rather than true rotational vertigo. Associated systemic symptoms. |

The patient's age and vascular risk profile are important factors when considering VBI [1].

Treatment of Vertigo and VBI

Treatment must address both the symptomatic vertigo (if present and severe) and, more importantly, the underlying cause of the Vertebro-Basilar Insufficiency to prevent future Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIAs) and potentially devastating strokes [1, 7].

1. Management of Underlying VBI Cause (Secondary Stroke Prevention) [7]:

- Medical Therapy: This is the mainstay.

- Antiplatelet Agents: Standard for VBI caused by atherosclerosis (e.g., Aspirin, Clopidogrel).

- Anticoagulation: Used primarily for VBI caused by cardioembolism (atrial fibrillation) or arterial dissection.

- Statin Therapy: High-intensity statins for patients with atherosclerotic disease.

- Aggressive Risk Factor Control: Strict management of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking cessation.

- Endovascular/Surgical Intervention (Selected Cases):

- Vertebral artery stenting (extracranial or intracranial) may be considered for severe symptomatic stenosis refractory to medical therapy, but risks must be weighed carefully, especially for intracranial lesions.

- Surgical bypass is rarely indicated.

- Treatment for subclavian steal syndrome (e.g., stenting or bypass of the subclavian artery).

2. Symptomatic Treatment of Vertigo [1]:

- Medications like antihistamines (e.g., meclizine), benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam), or antiemetics (e.g., prochlorperazine) can help suppress acute vertigo and nausea, but should generally be used short-term as they can impede long-term central compensation. These do not treat the underlying VBI.

- Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy: Physical therapy exercises can help the brain adapt and compensate for chronic dizziness or imbalance.

Lifestyle measures such as wearing a cervical collar are generally not indicated for VBI itself, unless specifically recommended for a condition like recent dissection or severe instability [1].

![]() Attention! VBI symptoms, including vertigo accompanied by other neurological signs, can be warning signs of an impending stroke. Prompt medical evaluation is essential if you or someone you know experiences these symptoms.

Attention! VBI symptoms, including vertigo accompanied by other neurological signs, can be warning signs of an impending stroke. Prompt medical evaluation is essential if you or someone you know experiences these symptoms.

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 15: Dizziness and Vertigo & Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases.

- Caplan LR. Caplan's Stroke: A Clinical Approach. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2016. Chapter on Posterior Circulation Stroke Syndromes.

- Grotta JC, Albers GW, Broderick JP, et al. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2021. Chapter on Mechanisms of Ischemic Stroke & Chapter on Vertebrobasilar Disease.

- Osborn AG, Hedlund GL, Salzman KL. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Stroke and Vascular Disease (Posterior Circulation).

- Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, Hsieh YH, et al. HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Oct;20(10):987-96.

- Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, et al; Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Mar;156(3_suppl):S1-S47. (Example guideline for peripheral vertigo diagnosis).

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014 Jul;45(7):2160-236. (Or more recent updates).

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis