Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

Communicating Hydrocephalus After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Overview

Communicating hydrocephalus is a frequent and significant complication that can arise following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [1, 2]. Unlike obstructive hydrocephalus where there is a physical blockage within the ventricular system, communicating hydrocephalus involves impaired absorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) back into the bloodstream, despite CSF being able to flow freely between the ventricles and into the subarachnoid space [1, 2]. This leads to an accumulation of CSF, ventricular enlargement, and increased intracranial pressure (ICP) [1].

Pathophysiology and Definition

Following the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm, which typically causes subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (bleeding into the space surrounding the brain), communicating hydrocephalus is a common and significant complication [1, 2]. "Communicating" means that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can still flow freely between the ventricles and out into the subarachnoid space; the problem lies outside the ventricular system [1].

The primary cause is impaired CSF absorption [1, 2]. Blood products from the SAH circulate within the CSF and can inflame, scar, or physically clog the arachnoid granulations – specialized structures primarily located along the superior sagittal sinus that are responsible for reabsorbing CSF back into the bloodstream [1]. When absorption is reduced but CSF production continues at a normal rate, CSF accumulates, leading to increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and enlargement (dilation) of the brain's ventricles (lateral, third, and fourth) [1].

This is distinct from *obstructive* (non-communicating) hydrocephalus, where a blockage *within* the ventricular pathways (e.g., by a blood clot from associated intracerebral or intraventricular hemorrhage, or by a mass) prevents CSF flow between ventricles [1].

Timing and Risk Factors

Communicating hydrocephalus can develop at different time points after SAH [1]:

- Acute Hydrocephalus: May occur within the first few days, often related to the initial mass effect of blood clots obstructing CSF pathways or early impairment of absorption.

- Subacute/Chronic Hydrocephalus: More typically develops days to weeks (commonly within the first 3 weeks, but can be later) after the initial hemorrhage, as inflammatory and scarring processes affect the arachnoid granulations.

The main risk factor is the amount and location of subarachnoid blood [1, 2]. Patients with a large volume of blood on initial CT scan, particularly concentrated in the basal cisterns (like the ambient and suprasellar cisterns) where CSF pathways are critical, are at higher risk for developing hydrocephalus [1, 2].

Clinical Presentation

The symptoms of communicating hydrocephalus after SAH can vary depending on the acuity and severity [1]:

- Acute Presentation: Often manifests as neurological deterioration in a patient already being monitored for SAH. This can include:

- Decreased level of consciousness (drowsiness progressing to stupor or coma).

- Worsening headache.

- Nausea/vomiting.

- Changes in vital signs or pupillary responses indicating rising ICP.

- Subacute/Chronic Presentation: May develop more gradually, sometimes weeks after the initial bleed, and can resemble Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH). The classic (though not always complete) "Hakim Triad" includes:

- Gait Disturbance: Often the first and most prominent symptom; characterized by difficulty initiating steps, shuffling, magnetic gait (feet stuck to the floor), and instability.

- Cognitive Decline: Problems with memory, attention, executive function, apathy, slowed thinking.

- Urinary Incontinence: Typically urgency or frequency initially, progressing to frank incontinence.

Importantly, some degree of ventricular enlargement on imaging may occur without causing clear symptoms initially, requiring careful clinical correlation [1].

Diagnosis and Imaging

Diagnosis relies on clinical suspicion combined with neuroimaging [1, 2, 3]:

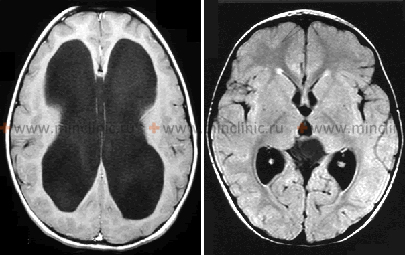

- Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Brain: These imaging studies are essential to visualize the ventricles. Key findings include:

- Ventriculomegaly: Enlargement of the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles, often out of proportion to any associated cerebral atrophy.

- Features suggesting impaired CSF flow/absorption: Periventricular lucency/edema (transependymal CSF seepage), effacement of cortical sulci over the convexity, rounding of the frontal horns.

- The Evans' index (ratio of maximum frontal horn width to maximum inner skull diameter) > 0.3 is often used as a quantitative indicator.

- Correlation with Clinical Symptoms: Imaging findings must be interpreted in the context of the patient's clinical presentation. Ventricular enlargement alone is not sufficient for diagnosis; symptomatic hydrocephalus requires both imaging evidence and relevant clinical signs.

- Lumbar Puncture (LP): Can measure opening pressure (may be elevated, normal, or low depending on the stage and compliance) and allows for CSF removal (diagnostic "tap test," where temporary symptom improvement after removing 30-50cc CSF supports the diagnosis, especially for chronic hydrocephalus). CSF analysis also rules out infection. *Caution is needed if there's any suspicion of non-communicating hydrocephalus or mass effect, where LP could risk herniation.*

Differential Diagnosis of Ventriculomegaly/Hydrocephalus Symptoms After SAH [1, 3]

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Imaging / CSF Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Communicating Hydrocephalus (Post-SAH) | Develops days/weeks after SAH. Gait disturbance, cognitive decline, incontinence (chronic triad). Or acute decline in LOC. Due to impaired CSF absorption. | CT/MRI: Ventriculomegaly (all ventricles enlarged) disproportionate to atrophy. Normal/patent CSF pathways. LP: Pressure variable (high/normal/low), CSF composition usually normal (unless recent bleed). Positive response to CSF drainage. |

| Obstructive Hydrocephalus (Acute Post-SAH) | Sudden decline in LOC, headache, vomiting. Often due to IVH or large ICH blocking aqueduct or 4th ventricle outlets. | CT/MRI: Enlargement of ventricles *proximal* to obstruction (e.g., lateral & 3rd ventricles enlarged, 4th ventricle normal/small). Obstructing lesion (clot, mass) visible. LP contraindicated. |

| Delayed Cerebral Ischemia (DCI) due to Vasospasm | Typically 4-14 days post-SAH. New focal neurological deficit (hemiparesis, aphasia) or decline in LOC. May have associated headache. | CT head often normal initially (no new bleed/hydrocephalus). CT Perfusion/MRI may show ischemia. Angiography confirms vasospasm. TCD shows high velocities. |

| Aneurysmal Rerupture | Sudden, catastrophic decline in LOC, often severe headache increase, new deficits. Highest risk early. | Repeat Head CT shows new/increased hemorrhage (SAH, IVH, ICH). |

| Cerebral Edema | Swelling around initial hemorrhage site or due to vasospasm-related infarction. Can cause increased ICP, decline in LOC, herniation. | CT/MRI shows edema (low density/T2 bright), mass effect, midline shift. Ventricles may be compressed initially, not enlarged. |

| Seizures / Status Epilepticus | Can cause altered LOC or transient focal deficits (Todd's). | EEG confirms seizure activity. Imaging excludes new structural cause. |

| Systemic Complications (e.g., Sepsis, Hyponatremia) | Altered mental status may be due to infection, electrolyte imbalance, hypoxia, etc. | Relevant systemic workup (labs, cultures). Normal head imaging usually. |

| Cerebral Atrophy (Ex Vacuo Ventriculomegaly) | Enlarged ventricles due to loss of brain tissue (e.g., prior stroke, neurodegeneration), not impaired CSF dynamics. Often associated with cognitive decline but usually not gait/incontinence triad. | CT/MRI shows ventriculomegaly proportional to sulcal enlargement/atrophy. LP pressure normal. No response to CSF drainage. |

Treatment Approaches

Management depends on the severity of symptoms and the acuity of the presentation [1, 2].

- Conservative Management / Monitoring: Mild ventricular enlargement without significant symptoms might be monitored with serial imaging and clinical assessments, as some cases may stabilize or resolve, particularly if the initial SAH burden was low [1].

- Temporary CSF Diversion: For acute symptomatic hydrocephalus causing neurological decline, temporary CSF drainage is often necessary [1, 2]:

- External Ventricular Drain (EVD): A catheter placed into one of the lateral ventricles and connected to an external drainage system to remove CSF and monitor ICP. Accurate knowledge of the ruptured aneurysm's location (if not yet secured) is crucial to avoid injury during EVD placement.

- Lumbar Drain (LD): A catheter placed in the lumbar subarachnoid space for drainage. Can only be used if hydrocephalus is confirmed to be communicating and there is no significant intracranial mass effect.

- Permanent CSF Diversion (Shunting): If hydrocephalus persists and remains symptomatic, or for chronic hydrocephalus, a permanent shunt is typically required [1, 2]. This involves surgically implanting a system to divert excess CSF to another body cavity where it can be absorbed [4]:

- Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) Shunt: Most common type; drains CSF from a ventricle to the peritoneal cavity in the abdomen.

- Lumboperitoneal (LP) Shunt: Drains CSF from the lumbar subarachnoid space to the peritoneal cavity; only suitable for communicating hydrocephalus with normal or low pressure.

- Other types (e.g., ventriculoatrial, ventriculopleural) are less common.

- Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy (ETV): A procedure sometimes used for *obstructive* hydrocephalus, creating a hole in the floor of the third ventricle to bypass a blockage [4]. It is generally *not* effective for communicating hydrocephalus where the primary problem is absorption [1].

The decision to place a permanent shunt is based on persistent symptoms and imaging findings, often aided by the response to temporary drainage (EVD or LP tap test) [1, 2].

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases (Section on Complications of SAH, including Hydrocephalus).

- Connolly ES Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012 Jun;43(6):1711-37.

- Osborn AG, Hedlund GL, Salzman KL. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Hydrocephalus.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 9th ed. Thieme; 2019. Chapter 17: Hydrocephalus & Chapter 18: Cerebrospinal Fluid Shunts.

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis