Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral Hemorrhage after Head Injury (Traumatic Brain Injury - TBI)

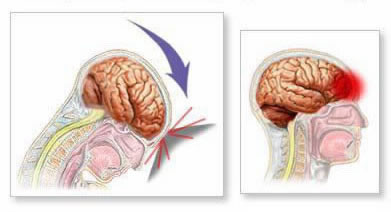

Head trauma is a common cause of intracranial bleeding [1, 2]. Depending on the mechanism and severity of injury, trauma can result in various types of hemorrhage, including intracerebral hematoma (bleeding within the brain parenchyma), posterior fossa hematomas (subtentorial, affecting cerebellum or brainstem), subarachnoid hemorrhage (bleeding into the space around the brain), acute or chronic subdural hematoma (bleeding beneath the dura mater), and acute epidural hematoma (bleeding between the dura mater and the skull) [1, 2]. Traumatic intracerebral hematomas (contusions that coalesce into larger bleeds) frequently occur in specific locations susceptible to coup-contrecoup injuries, such as the temporal lobes (particularly the tips) and the inferior frontal lobes [1, 2].

It is crucial to consider traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with acute neurological deficits of unknown origin, especially if the onset occurred after a fall or other potential injury, even if seemingly minor [1]. Symptoms like hemiparesis (weakness on one side), stupor (decreased responsiveness), or disorientation can mimic an acute stroke. Prompt brain imaging, typically starting with a non-contrast CT scan, is essential for diagnosis [2, 3]. MRI may provide more detail about associated injuries [3]. While angiography is not routinely required for simple traumatic hematomas, it may be considered if there is suspicion of an underlying vascular injury (e.g., traumatic aneurysm or dissection) contributing to the hemorrhage [1]. Rapid diagnosis is vital as surgical intervention (evacuation of the hematoma) can be life-saving in cases of significant mass effect or elevated intracranial pressure [2].

Intracerebral Hemorrhage Associated with Coagulopathy and Hematopoietic Disorders

Intracerebral hemorrhage can be a serious complication in patients with underlying hematologic disorders or coagulopathies (disorders of blood clotting) [1, 4]. Conditions such as leukemia, aplastic anemia (bone marrow failure), and thrombocytopenic purpura (conditions with severely low platelet counts, like ITP or TTP) impair the body's ability to form clots and stop bleeding [1, 4]. Hematomas associated with these systemic hematologic disorders can occur spontaneously at any location within the brain (intracranial) and may sometimes present as multiple simultaneous intracerebral hemorrhages [1]. A potential diagnostic clue in these patients is the frequent presence of visible hemorrhages elsewhere in the body, such as petechiae or purpura on the skin and bleeding from mucous membranes (e.g., gums, nosebleeds) [1].

Intracerebral hemorrhages occurring in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy (like warfarin, heparin, or direct oral anticoagulants) can also develop at any intracerebral location [1, 5]. These hemorrhages may sometimes evolve more slowly or re-bleed over the initial 24-48 hours compared to typical hypertensive hemorrhages [5]. Prompt recognition and management are critical. In patients with coagulopathy (e.g., due to anticoagulants or liver disease) complicated by intracerebral hemorrhage, emergency reversal of the coagulopathy is often indicated, potentially involving agents like vitamin K, prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs), or fresh frozen plasma (FFP), depending on the specific cause [5]. If significant intracerebral hemorrhage occurs in a patient taking antiplatelet agents like aspirin or clopidogrel, platelet transfusion may be considered in certain situations (especially if emergency neurosurgery is needed), although its benefit in improving outcomes is controversial and not routinely recommended for spontaneous ICH [5].

Hemorrhage into a Brain Tumor

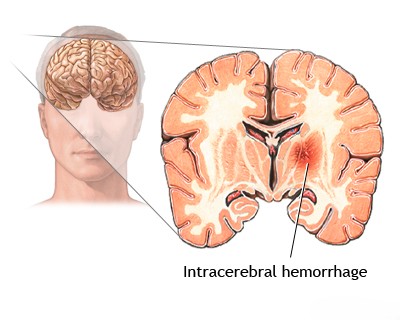

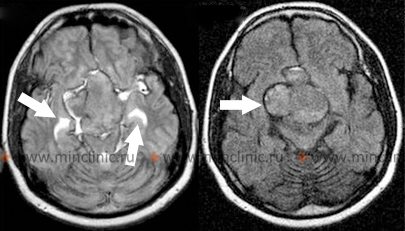

Bleeding directly within a primary or metastatic brain tumor (intratumoral hemorrhage) can sometimes be the initial clinical presentation leading to the diagnosis of an intracerebral neoplasm [1, 6]. Certain types of brain tumors are more prone to hemorrhage than others [6]. Common metastatic brain tumors associated with a relatively high risk of bleeding include choriocarcinoma, malignant melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and certain types of lung cancer (bronchogenic carcinoma) [1, 6]. Among primary brain tumors, glioblastoma multiforme (the most common malignant primary brain tumor in adults) and, less commonly, medulloblastoma (a common malignant brain tumor in children, typically located in the cerebellum) are known to occasionally present with or develop intratumoral hemorrhage [1, 6].

Other Causes of Intracerebral and Spinal Hemorrhage

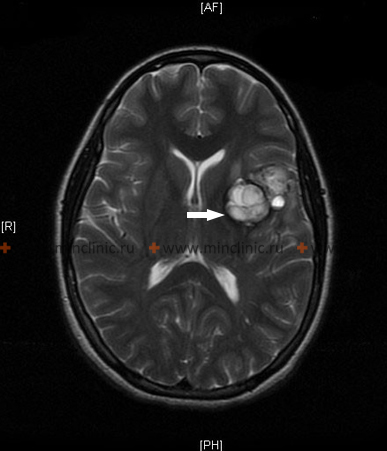

Occasionally, patients present with intracerebral hemorrhages where the underlying etiology remains initially unknown after standard investigations [1]. These cryptogenic hemorrhages may sometimes be secondary to small, underlying vascular lesions that are difficult to detect on initial imaging, such as small angiographically occult vascular malformations (e.g., cavernous malformations, developmental venous anomalies with associated hemorrhage), small arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), or microaneurysms [1, 7]. Another important cause, particularly of lobar hemorrhages in the elderly, is cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a condition where amyloid protein deposits weaken the walls of small-to-medium sized cortical and leptomeningeal arteries, making them prone to rupture [1, 7].

Primary intraventricular hemorrhage (bleeding originating solely within the ventricles) is rare in adults and often suggests an underlying intraventricular tumor, AVM, or aneurysm rupture near the ventricle [1]. More commonly, intraventricular hemorrhage is secondary to a nearby parenchymal hemorrhage (e.g., hypertensive bleed in the basal ganglia or thalamus) rupturing and extending into the ventricular system [1]. This extension into the ventricles can sometimes occur without causing the typical focal neurological symptoms expected from the parenchymal component [1].

Certain types of encephalitis can have hemorrhagic features [1]. Hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis is a severe, often fulminant, inflammatory condition characterized pathologically by numerous small, punctate hemorrhages (petechiae) predominantly in the white matter [1]. Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) typically does not reveal visible blood (gross xanthochromia or high RBC count) in this condition, helping distinguish it from larger hemorrhages [1]. This pattern of petechial hemorrhage is sometimes associated with severe systemic infections, such as gram-negative bacterial sepsis, or certain viral infections [1].

In herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis, which typically affects the temporal lobes, hemorrhagic necrosis is a common feature, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis may reveal the presence of red blood cells (erythrocytes) along with elevated white blood cells and protein [1].

Secondary brainstem hemorrhages (often called Duret hemorrhages) can occur as a consequence of severe increased intracranial pressure causing downward transtentorial herniation, leading to stretching and tearing of small perforating arteries supplying the brainstem [1]. These typically occur in patients who are already comatose due to the primary brain injury (e.g., large supratentorial hemorrhage or tumor) and do not present with the typical focal neurological signs of a primary brainstem stroke [1].

Systemic vasculitis (arteritis), particularly conditions like polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), can rarely involve cerebral vessels and lead to central nervous system hemorrhage, sometimes associated with underlying hypertension which can also be related to the systemic disease (e.g., lupus nephritis) [1].

Hemorrhage within the spinal cord (hematomyelia) or surrounding spaces (epidural or subdural hematoma) is much less common than intracranial hemorrhage [1, 8]. Spinal cord hemorrhage is typically caused by underlying spinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), cavernous malformations, or metastatic tumors [1, 8]. Spinal epidural hemorrhage (bleeding into the space outside the dura mater surrounding the spinal cord), often related to anticoagulation, trauma, or procedures like lumbar puncture, can cause rapid compression of the spinal cord, leading to severe pain and rapidly progressive neurological deficits (e.g., weakness, paralysis) [1, 8]. This represents a neurological emergency requiring immediate recognition and often urgent surgical intervention (decompression) to prevent permanent paraplegia or quadriplegia [8].

Differential Diagnosis of Intracranial Hemorrhage [1, 3, 7, 9]

| Type / Cause | Typical Location / Features | Common Associations / Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertensive ICH | Deep structures: Basal ganglia (putamen), thalamus, pons, cerebellum. | Chronic hypertension (most common overall cause). |

| Lobar ICH (Non-traumatic) | Superficial (cortical/subcortical) within cerebral lobes. | Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA) in elderly; AVM, cavernoma, tumor hemorrhage possible at any age. Anticoagulation. |

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) | Blood in subarachnoid space (cisterns, sulci). "Thunderclap" headache. | Ruptured saccular aneurysm (~85%); AVM, trauma, other vascular malformations. |

| Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH, SDH, EDH, SAH) | ICH: Frontal/temporal lobes (contusions). SDH: Crescentic, crosses sutures. EDH: Lenticular, doesn't cross sutures, often with fracture. SAH: Can occur with trauma. | History of head trauma. Location depends on impact/mechanism. |

| Hemorrhage into Tumor | Bleeding within a pre-existing mass lesion. | Primary (e.g., Glioblastoma) or metastatic tumors (e.g., melanoma, RCC, chorio, lung). |

| Vascular Malformation Hemorrhage (AVM, Cavernoma) | Location depends on malformation site. Often parenchymal +/- intraventricular/subarachnoid. | Underlying AVM or cavernoma identified on imaging (MRI/Angiography). |

| Anticoagulant-Associated ICH | Can occur anywhere. May be larger or expand more than non-anticoagulated bleeds. | Use of warfarin, heparin, DOACs. Coagulation studies (INR, PTT) abnormal. |

| Hematologic Disorder / Coagulopathy | Can occur anywhere, may be multiple. Associated systemic bleeding often present. | Leukemia, aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, liver disease, DIC. Abnormal blood counts/coagulation panel. |

| Hemorrhagic Transformation of Ischemic Stroke | Bleeding occurs within an area of prior infarction, often days later. | Imaging shows hemorrhage within established infarct territory. Often follows large embolic strokes or reperfusion therapy. |

| Cerebral Venous Thrombosis (CVT) | Can cause venous infarcts which are often hemorrhagic. Headache, seizures common. | MRV/CTV confirms sinus/vein thrombosis. MRI shows venous infarct +/- hemorrhage. |

| Vasculitis | Rare cause. May cause hemorrhage or infarction. Often systemic symptoms. | Inflammatory markers (ESR/CRP) may be high. Angiography may show vessel irregularities. Biopsy may be needed. |

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases (Section on Intracerebral Hemorrhage).

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 9th ed. Thieme; 2019. Chapter 29: Head Trauma.

- Osborn AG, Hedlund GL, Salzman KL. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Trauma.

- Hoffman R, Benz EJ Jr, Silberstein LE, et al. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2018. Section on Hemostasis and Thrombosis (or specific chapters on bleeding disorders).

- Hemphill JC 3rd, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Jul;46(7):2032-60.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 9th ed. Thieme; 2019. Chapter 20: Brain Tumors (sections on specific tumor types and complications like hemorrhage).

- Osborn AG, Hedlund GL, Salzman KL. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Vascular Malformations and Intracranial Hemorrhage.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 9th ed. Thieme; 2019. Chapter 31: Spinal Cord Injury & Chapter 40: Spinal Vascular Malformations.

- Grotta JC, Albers GW, Broderick JP, et al. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2021. Chapter on Intracerebral Hemorrhage.

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis