Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis with Bruit ("Noise") Overview

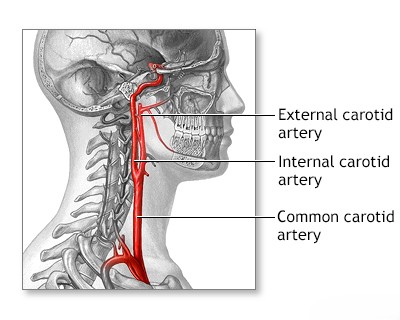

The precise etiology (cause) and origin of a carotid bruit – a "whooshing" sound heard with a stethoscope over the carotid artery bifurcation in the neck – remain subjects of discussion, especially when it occurs in the presence of atherosclerotic lesions that have not yet caused symptoms like a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke (i.e., asymptomatic stenosis) [1, 2]. Historically, many published studies investigating this phenomenon, often based on small patient groups, had limitations in accurately determining the exact location and severity (degree) of the underlying carotid bifurcation stenosis responsible for the bruit [1].

Studies examining patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis and an audible cervical bruit, particularly those focusing on outcomes after vascular surgery, often share similar methodological limitations from the past [1]. It is generally accepted that patients with a cervical bruit have an increased overall risk of cardiovascular disease, subsequent stroke (not necessarily related to the bruit itself), and mortality [1, 4]. Importantly, a stroke, when it occurs in these patients, may not necessarily originate from the vascular territory supplied by the stenotic artery causing the bruit (it could be from the other carotid artery, the heart, or elsewhere) [1, 4]. Therefore, the mere presence of an asymptomatic carotid bruit is not, by itself, a universal indication for carotid artery intervention (like surgery or stenting) [1, 5].

However, specific subgroups are at higher risk. Patients identified as having severe stenosis specifically at the proximal internal carotid artery (often defined by imaging as a residual lumen ≤ 1.5 mm), which may result in reduced distal cerebral blood flow, face an increased risk of subsequent thrombotic occlusion (complete blockage) of the artery [1, 6].

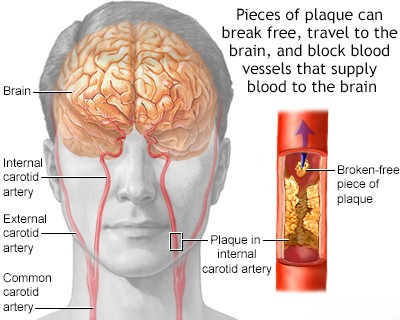

Although these patients with severe stenosis may experience reduced blood flow distal to the lesion, they often remain asymptomatic initially [1]. This is frequently due to adequate collateral blood flow compensating via the Circle of Willis, particularly through the ipsilateral (same side) anterior communicating artery or posterior communicating artery, supplying the middle and anterior cerebral artery territories [1, 7]. Therefore, even with severe stenosis, a stroke (cerebral infarction), when it occurs, might develop later due to arterio-arterial embolism (fragments breaking off the plaque) rather than purely low flow [1, 6]. The characteristics of the bruit associated with stenosis at the proximal internal carotid artery can sometimes offer clues: when high-pitched and prolonged, extending into diastole (the heart's resting phase), it often suggests significant stenosis [1, 2]. As the stenosis progresses towards complete occlusion, reducing cerebral blood flow further, the turbulent flow diminishes, causing the bruit to lessen and eventually disappear when the artery fully occludes [1, 2].

Modern non-invasive carotid artery studies are essential for identifying and quantifying significant stenosis [5]. These include B-mode ultrasound (visualizing the plaque), Doppler ultrasound (USDG) to measure blood flow velocities distal to the stenosis, quantitative spectral analysis of the bruit itself (less common now), and historically, techniques like oculoplethysmography for determining relative eye artery pressures (rarely used today) [1, 8]. Carotid Duplex ultrasound, combining B-mode and Doppler, is the primary screening and surveillance tool [5, 8].

Regarding treatment, large randomized controlled trials (like ACAS [9] and ACST [10]) have compared outcomes for carotid endarterectomy (surgical removal of plaque) plus medical therapy versus medical therapy alone (including antiplatelet agents like aspirin, statins, and blood pressure control) in patients with significant asymptomatic carotid stenosis. While these trials showed a modest benefit for surgery in reducing long-term stroke risk for carefully selected patients with high-grade stenosis (typically >60-70% depending on the trial and measurement method) treated at centers with low complication rates, the absolute risk reduction is small, meaning many patients undergo surgery without deriving benefit [5, 9, 10]. Therefore, treatment decisions must be highly individualized [5]. Antiplatelet agents (like aspirin) and optimal medical management (statins, BP control, lifestyle changes) are fundamental for all patients [5, 11]. If significant, progressive stenosis is documented via serial imaging (Doppler ultrasound, CT angiography, or MR angiography), particularly if the residual arterial lumen narrows to ≤ 1.5 mm (indicating very severe stenosis), surgical intervention (endarterectomy) or possibly carotid artery stenting may be considered in appropriate candidates after careful risk/benefit discussion [1, 5, 12].

The procedural complication rate (stroke or death) for asymptomatic carotid endarterectomy should ideally be very low (e.g., ≤ 2-3% as per trial standards) for the potential benefits to outweigh the risks [5, 9, 10]. Similarly, carotid stenting also carries procedural risks [12, 13]. Despite trial data, there remains ongoing debate and a need for personalized assessment regarding the superiority of intervention over modern optimal medical management alone for many patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis, emphasizing the need for shared decision-making between physician and patient [5, 13].

Differential Diagnosis of Cervical Bruit [1, 2, 14]

While a carotid bruit often indicates underlying carotid artery stenosis due to atherosclerosis, other conditions can also produce similar sounds in the neck. Differentiating the cause is important for assessing stroke risk and determining appropriate management.

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Carotid Artery Stenosis (Internal/Bifurcation) | Systolic bruit, often high-pitched, loudest over bifurcation/angle of jaw. May radiate up neck. Associated with atherosclerotic risk factors. May be asymptomatic or cause TIA/stroke. | Carotid Duplex Ultrasound (shows plaque, measures stenosis). CTA/MRA confirms degree/location of stenosis. |

| External Carotid Artery (ECA) Stenosis | Systolic bruit, may be higher in neck, radiate towards ear/jaw. Less commonly associated with stroke than ICA stenosis. | Carotid Duplex Ultrasound can identify ECA origin disease. CTA/MRA confirms. |

| Transmitted Cardiac Murmur (e.g., Aortic Stenosis) | Systolic bruit heard over carotids, but loudest over precordium (heart). Often radiates widely into neck. Associated cardiac symptoms/signs may be present. | Cardiac auscultation reveals primary murmur. Echocardiogram confirms valvular disease. Carotid Duplex may be normal or show unrelated atherosclerosis. |

| Arteriovenous Fistula/Malformation (AVF/AVM) | Rare cause. Continuous bruit (systolic & diastolic). May have palpable thrill or associated pulsatile mass/swelling in neck or head. | Clinical exam. Duplex US may show high flow/turbulence. CTA/MRA/DSA confirms abnormal vascular connection. |

| Thyrotoxicosis / Severe Anemia / High Output States | Systolic flow murmur over carotids or thyroid gland due to increased blood flow/turbulence. Not localized stenosis bruit. Associated systemic symptoms (tachycardia, palpitations, fatigue, weight loss, goiter). | Clinical signs of underlying condition. Thyroid function tests (TFTs), Complete Blood Count (CBC). Cardiac evaluation. Carotid Duplex usually normal. |

| Venous Hum | Continuous, low-pitched humming sound. Changes significantly or disappears with head rotation or light compression of jugular vein. Common in children, usually benign. | Clinical auscultation with maneuvers is key. Usually no further investigation needed if typical. |

| Subclavian/Vertebral Artery Stenosis | Bruit may be heard lower in neck/supraclavicular fossa. May radiate. Can cause subclavian steal syndrome (arm claudication, posterior circulation symptoms with arm use, differential arm BPs). | Clinical exam (arm BPs). Duplex US of subclavian/vertebral arteries. CTA/MRA of neck/chest vessels. |

| Fibromuscular Dysplasia (FMD) | Non-atherosclerotic cause of stenosis, often affecting mid-ICA or vertebral arteries. Younger patients typically (esp. women). May have bruits, headache, dissection risk. | CTA/MRA/DSA shows characteristic "string of beads" appearance or focal stenosis. |

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases (Section on Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis and Bruit).

- Swartz RH, Gladstone DJ, Hachinski V. Auscultation for carotid bruits. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on [Date of Access - replace this]). Or a similar review article/textbook section on physical examination.

- Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases. 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates; 2010. Chapter 4: Blood Supply, Meninges, and Venous Drainage.

- Pickett CA, Jackson JL, Hemann BA, Atwood JE. Carotid bruit as a predictor of cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2010 Aug;211(2):365-71.

- Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Stroke Association; American Association of Neuroscience Nurses; American Association of Neurological Surgeons; American College of Radiology; American Society of Neuroradiology; Congress of Neurological Surgeons; Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Interventional Radiology; Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery; Society for Vascular Medicine; Society for Vascular Surgery. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Stroke. 2011 Aug;42(8):e464-540. (Or more recent updates/guidelines).

- Caplan LR. Caplan's Stroke: A Clinical Approach. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2016. Chapter on Large Artery Atherosclerosis.

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases, section on Collateral Circulation.

- Grant EG, Benson CB, Moneta GL, et al. Carotid artery stenosis: gray-scale and Doppler US diagnosis--Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference. Radiology. 2003 Nov;229(2):340-6. (Or more recent SRU guidelines).

- Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995 May 10;273(18):1421-8.

- Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, Thomas D; MRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) Collaborative Group. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004 May 8;363(9420):1491-502. (And subsequent long-term follow-up publications).

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014 Jul;45(7):2160-236.

- Naylor AR. Time to Rethink Management of Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis. Stroke. 2012 Jan;43(1):290-4. (Example of review discussing intervention choices).

- Brott TG, Howard G, Roubin GS, et al; CREST Investigators. Long-Term Results of Stenting versus Endarterectomy for Carotid-Artery Stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 17;374(11):1021-31. (And other relevant CAS vs CEA trials like ICSS, SPACE).

- Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG, Hoffman RM. Bates' Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 13th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2021. Chapter on Peripheral Vascular System.

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis