Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis

Overview: Suppurative Sigmoid Sinus Thrombosis

Suppurative Sigmoid Sinus Thrombophlebitis with Thrombosis is a serious intracranial complication, most commonly arising from infections of the middle ear and mastoid air cells (otogenic origin) [1, 2]. It can also, less frequently, result from facial infections (e.g., furuncles) spreading via venous pathways [1].

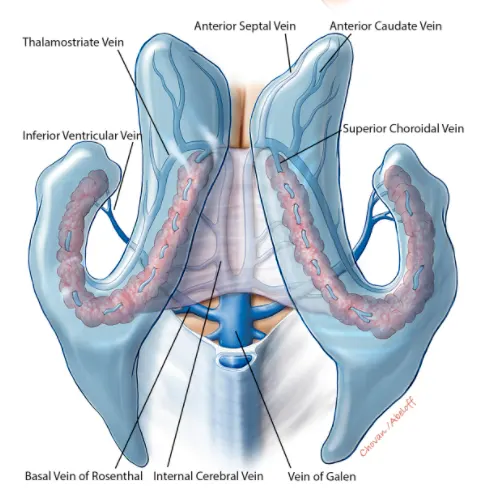

The sigmoid sinus, a large dural venous sinus, is vulnerable due to its close proximity to the mastoid bone; inflammation can spread directly, or via small emissary veins draining the mastoid into the sinus [1]. While other sinuses like the transverse, cavernous, or superior/inferior petrosal sinuses can be involved (often by extension), the sigmoid sinus is frequently the primary site in otogenic cases [1, 2]. This complication occurs with roughly equal frequency in acute and chronic suppurative otitis media (especially when complicated by cholesteatoma) [1].

Imaging techniques like Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) are crucial when sigmoid sinus thrombophlebitis or thrombosis is suspected.

Causes and Pathogenesis

The infectious agents are typically bacteria commonly found in ear infections, including Streptococcus species (especially S. pneumoniae), Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, anaerobic bacteria, and often a mixed bacterial flora [1, 2].

The process usually begins with the spread of infection from the middle ear or mastoid to the adjacent sigmoid sinus wall (periphlebitis) [1]. This may occur through direct extension via bone erosion or through thrombophlebitis of small communicating veins [1]. A perisinus abscess (pus collection adjacent to the sinus wall) may form [1].

Inflammation causes the outer sinus wall (dura) to thicken and change color (from blue to yellowish-gray) [1]. If untreated, the inflammation progresses to involve the inner endothelial lining of the sinus [1]. Damage to the endothelium, combined with inflammatory changes in blood composition and slowed blood flow within the sinus, promotes the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) – initially often mural (attached to the wall) and potentially progressing to become occlusive (blocking the sinus) [1, 2].

While thrombus formation can initially be a protective mechanism attempting to wall off the infection, it becomes a dangerous complication [1]. The thrombus often becomes infected (septic thrombus), potentially breaking off into infected emboli or serving as a persistent source of bacteria entering the bloodstream [1, 2].

Thrombosis can remain localized to the sigmoid sinus or propagate [1, 2]:

- Retrograde: Extending backwards into the transverse sinus, potentially to the confluence of sinuses or even the contralateral side.

- Antegrade: Spreading downwards into the jugular bulb and internal jugular vein (IJV), potentially as far as the innominate vein.

- Into connecting sinuses: Such as the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses, potentially reaching the cavernous sinus.

Complications arise from the infected thrombus [1, 2]:

- Sepsis: Bacteria or infected emboli entering the systemic circulation. Metastatic infections can occur, commonly affecting the lungs (septic pulmonary emboli, especially with chronic otitis), joints, muscles, or subcutaneous tissue.

- Intracranial Spread: Retrograde thrombosis into cortical or cerebellar veins can lead to venous infarction or brain abscess formation (cerebellum or temporal/occipital lobes). Direct extension through the sinus wall can also cause meningitis or brain abscess.

Rarely, sepsis (termed osteophlebitic pyemia) can arise from infection spreading from multiple small thrombosed veins within the mastoid bone itself, even without large sinus thrombosis [1].

Sepsis and Systemic Inflammatory Response

Otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis is a potent cause of sepsis, a life-threatening condition characterized by the body's dysregulated response to infection, leading to organ dysfunction [1]. Historically, this was often described in terms of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), which involves criteria like altered temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and white blood cell count [1]. While SIRS criteria help identify inflammation, the modern definition of sepsis emphasizes infection plus evidence of organ dysfunction [5].

Otogenic sepsis classically presents with [1]:

- High, spiking fevers: Temperatures rising sharply (e.g., to 40–41°C), often followed by rapid drops to normal or subnormal levels, frequently accompanied by drenching sweats. This pattern may occur once or multiple times daily.

- Rigors/Chills: Intense shaking chills often precede or accompany the temperature spikes.

- Metastatic Infections: Abscesses forming in distant sites like the lungs (septic pneumonia/emboli), joints (septic arthritis), muscles, or subcutaneous tissue.

Less commonly, sepsis may present as a more continuous fever without dramatic spikes or chills, but with evidence of septic organ damage (e.g., endocarditis, kidney injury, liver dysfunction, altered mental status due to severe systemic intoxication) [1].

The clinical presentation can vary [1]:

- In children, chills may be less common, and fever may be more constant.

- Adults may exhibit excitement/euphoria or lethargy/apathy.

- Pulse is typically rapid (tachycardia); persistent tachycardia after fever resolves is a poor prognostic sign.

- Appearance may be pale, sometimes with a jaundiced or grayish hue.

Blood tests in sepsis typically show [1]:

- Anemia (decreased hemoglobin), potentially with abnormal red blood cell forms (erythrocytes).

- High leukocyte count (leukocytosis) with a "left shift" (increased immature neutrophils), though leukopenia can occur in severe sepsis. Toxic granulation may be seen.

- Markedly elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP).

- Evidence of organ dysfunction (e.g., elevated creatinine, bilirubin, lactate; altered coagulation).

Monitoring trends in blood counts and inflammatory markers is important for assessing response to treatment [1].

Metastatic complications depend on the site: pulmonary abscesses can rupture into bronchi or pleura (empyema); joint infections can lead to destruction and ankylosis [1].

Clinical Symptoms

Symptoms of sigmoid sinus thrombosis can be subtle or dramatic, often overlapping with symptoms of the underlying ear infection, sepsis, or increased intracranial pressure (ICP) [1, 2].

Local Signs (often subtle or absent) [1]:

- Ear pain (otalgia), ear discharge (otorrhea) related to the primary otitis/mastoiditis.

- Pain, tenderness, or swelling over the mastoid process (behind the ear). Griesinger's sign (edema/tenderness over the mastoid emissary vein) is suggestive but uncommon and non-specific (can also occur with perisinus abscess).

- Tenderness or a palpable cord along the internal jugular vein in the neck (suggests IJV extension) is also uncommon and non-specific.

Signs of Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP) [1, 2]:

- Headache: Often severe, diffuse, and persistent.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Papilledema: Swelling of the optic disc seen on funduscopic examination (may take time to develop).

- Sixth Cranial Nerve (Abducens) Palsy: Causes double vision (diplopia), worse on looking towards the affected side. This is a non-localizing sign of increased ICP.

- Altered mental status: Drowsiness, confusion, lethargy, coma.

Focal Neurological Deficits [1, 2]:

- Seizures.

- Weakness or sensory loss (hemiparesis/hemisensory deficit) if venous infarction occurs.

- Other cranial nerve palsies (e.g., IX-XII at the jugular foramen - Vernet's syndrome) are rare, suggesting thrombosis extension to the jugular bulb or periphlebitis.

Signs of Sepsis (as described in Section 3) [1]:

- High spiking fevers, chills, tachycardia, altered mental status, signs of metastatic infection.

The classic, florid presentation of otogenic sepsis with obvious localizing signs is now less common due to the widespread use of antibiotics, which can mask or attenuate symptoms [1]. Diagnosis can be challenging, particularly if the underlying ear infection is chronic or partially treated. Patients may present primarily with headache, fever of unknown origin, or non-specific neurological decline [1].

Furthermore, complications like cerebral edema, venous infarction, meningitis, or brain/cerebellar abscess can dominate the clinical picture [1, 2].

Diagnosis

Diagnosing sigmoid sinus thrombosis requires a high index of suspicion, particularly in patients with a history of ear infections presenting with headache, fever, or neurological changes [1, 2].

- Clinical History and Examination: Focus on ear symptoms, fever pattern, headache characteristics, neurological deficits, and signs of sepsis or increased ICP [1]. Careful ear examination (otoscopy) is essential.

- Laboratory Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with differential (leukocytosis/left shift?).

- Inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP - usually elevated).

- Blood Cultures: Crucial to identify the causative organism and guide antibiotic therapy. Should be drawn ideally before starting antibiotics, preferably during fever spikes [1].

- Coagulation studies (if anticoagulation is considered or non-infectious causes suspected).

- Lumbar Puncture (LP): May be performed cautiously *after* ruling out significant mass effect or severely elevated ICP on imaging [1]. CSF analysis helps diagnose or exclude meningitis (elevated white cells, protein; low glucose; Gram stain/culture) [1]. Opening pressure measurement assesses ICP [1].

- Neuroimaging: Essential for confirming the diagnosis [1, 2, 3].

- MRI with MR Venography (MRV): The preferred imaging modality. MRI can show associated mastoiditis, brain abscesses, or venous infarcts. MRV directly visualizes the venous sinuses, demonstrating lack of flow signal within the thrombosed sinus. Contrast-enhanced MRI/MRV can help visualize the clot ("empty delta sign" on post-contrast axial images for superior sagittal sinus thrombosis, similar signs may apply) and assess sinus wall enhancement (thrombophlebitis).

- CT with CT Venography (CTV): An alternative, especially if MRI is unavailable or contraindicated. Contrast-enhanced CT can show the filling defect within the sinus ("empty delta sign"). CT is also excellent for evaluating the bony anatomy of the mastoid and middle ear for the source infection. Non-contrast CT is less sensitive for thrombosis but important initially to rule out hemorrhage or large mass lesions.

- Care must be taken to differentiate thrombosis from congenital sinus hypoplasia or atresia, which can appear similar (lack of flow) on venography. Evaluating the bony grooves for the sinuses on CT can help distinguish these (Figure A vs. B in the image below).

Differential Diagnosis of Sigmoid Sinus Thrombosis [1, 2, 3]

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Septic Sigmoid Sinus Thrombosis | History of otitis/mastoiditis (Otogenic complications). Headache, fever (often spiking/septic), +/- signs of increased ICP (papilledema, CN VI palsy), +/- focal deficits/seizures (if venous infarct/abscess). | MRI/MRV or CT/CTV shows thrombosis (filling defect/no flow) in sigmoid sinus +/- extension. CT Temporal Bone shows source. Blood cultures may be positive. Inflammatory markers high. |

| Aseptic Cerebral Venous Thrombosis (CVT) | Can affect any sinus. Headache common. Seizures, focal deficits, increased ICP possible. No clear infectious source. Risk factors (prothrombotic state, dehydration, pregnancy/postpartum, OCPs). | MRI/MRV or CT/CTV confirms thrombosis. No evidence of local infection source (e.g., mastoiditis). Workup for prothrombotic state. |

| Meningitis (Otogenic or other) | Headache, fever, neck stiffness, altered mental status. May have otitis history. Sinuses usually patent on venography unless co-existing thrombosis. | LP shows CSF evidence of meningitis. MRI may show leptomeningeal enhancement. Venography normal (unless thrombosis is also present). |

| Brain Abscess (Otogenic) | Headache, focal deficits (temporal lobe or cerebellar), +/- fever, seizures. Signs of increased ICP. May occur with or without sinus thrombosis. | MRI shows ring-enhancing parenchymal lesion with restricted diffusion. CT less sensitive. Venography may be normal or show concurrent thrombosis. |

| Epidural Abscess / Subdural Empyema (Otogenic) | Epidural: often subtle headache/fever. Subdural: rapid decline, high fever, meningismus, focal deficits, seizures. | MRI/CT with contrast shows epidural (lenticular) or subdural (crescentic) collection with dural/meningeal enhancement. Pus restricts diffusion (DWI). Venography may be normal or show concurrent thrombosis. |

| Otitic Hydrocephalus / Secondary IIH | Symptoms of increased ICP (headache, papilledema, CN VI palsy) in setting of otitis/mastoiditis. Normal/small ventricles. Often associated with sinus thrombosis. | MRI brain excludes mass/hydrocephalus. MRV often shows sinus thrombosis. LP shows elevated opening pressure, normal CSF composition. |

| Acute Mastoiditis (uncomplicated) | Postauricular pain, swelling, erythema; protruding auricle. Fever, otorrhea. No neurological signs or signs of increased ICP. | CT Temporal Bone shows mastoid opacification +/- bone destruction. Normal brain imaging/venography. |

Differential diagnosis includes other causes of headache and fever (e.g., meningitis, brain abscess unrelated to sinus thrombosis), other causes of increased ICP (e.g., tumor, idiopathic intracranial hypertension), malaria, typhoid fever, pneumonia, or tuberculosis if systemic symptoms predominate and the otogenic source is not obvious [1].

Treatment Strategies

Treatment of suppurative sigmoid sinus thrombosis requires a multidisciplinary approach involving neurologists, neurosurgeons, otolaryngologists (ENT), and infectious disease specialists [1, 2].

Core Components [1, 2]:

- Antibiotics: Prompt administration of high-dose, broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics is essential. Initial choices should cover common otogenic pathogens (Gram-positives, Gram-negatives, anaerobes). Therapy is then tailored based on culture results (blood or surgical specimens) and sensitivities. Duration is typically prolonged (e.g., 4-6 weeks or longer), guided by clinical and radiological response.

- Source Control: Surgical management of the underlying infection source is critical. This usually involves mastoidectomy (simple or radical, depending on the extent of disease) to drain infection from the middle ear and mastoid air cells. During surgery, the sigmoid sinus wall is typically exposed. If pus or granulation tissue is present (perisinus abscess/thrombophlebitis), drainage is performed. Sinusotomy (opening the sinus) and thrombectomy (removing the clot) were performed more routinely in the past but are less common now, reserved for specific situations like failure of medical management or associated abscess formation.

- Anticoagulation: The role of anticoagulation (e.g., heparin followed by warfarin or DOACs) in septic CVST is controversial and decided on a case-by-case basis [2, 6].

- Arguments For: May prevent thrombus propagation, promote recanalization, and potentially reduce the risk of venous infarction or pulmonary embolism (if thrombus extends down the IJV).

- Arguments Against: Risk of hemorrhagic transformation of venous infarcts, potential for bleeding into infected areas or surgical sites, theoretical concern about disseminating infection (though evidence is limited).

- Current Practice: Often considered, especially if there is significant thrombus burden, evidence of propagation, neurological worsening attributed to thrombosis (rather than infection/ICP), or co-existing risk factors for thrombosis. It is generally *avoided* if there is significant associated intracranial hemorrhage or uncontrolled infection/abscess requiring imminent drainage. Careful monitoring (prothrombin time/INR for warfarin, anti-Xa levels for some DOACs/heparin) is required if used.

- Supportive Care: Management of sepsis (fluid resuscitation, vasopressors if needed), management of increased ICP (head elevation, osmotic agents like mannitol/hypertonic saline, potentially CSF drainage via EVD/LP if safe), seizure prophylaxis/treatment if seizures occur.

Close monitoring of neurological status, vital signs, and inflammatory markers is essential [1]. Repeat imaging (MRI/MRV or CT/CTV) may be performed to assess thrombus evolution and response to treatment [1, 3].

With timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment combining antibiotics, often source control surgery, and potentially anticoagulation, the prognosis has significantly improved compared to the pre-antibiotic era, although mortality and long-term neurological sequelae can still occur, especially if diagnosis is delayed or complications like large venous infarcts or uncontrolled sepsis develop [1, 2].

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases (Section on Cerebral Venous Thrombosis).

- Ferro JM, Bousser MG, Canhão P, et al; ISCVT Investigators. European Stroke Organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis - endorsed by the European Academy of Neurology. Eur J Neurol. 2017 Oct;24(10):1203-1213.

- Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council and the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011 Apr;42(4):1158-92.

- Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases. 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates; 2010. Chapter 4: Blood Supply, Meninges, and Venous Drainage.

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

- Coutinho JM, Zuurbier SM, Stam J. Declining mortality in cerebral venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Stroke. 2014 Mar;45(3):e48-51. (Discusses outcomes and potentially anticoagulation).

- Osborn AG, Hedlund GL, Salzman KL. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Venous Thrombosis and Infarction.

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis