Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Cerebrovascular Diseases: Overview

- Ischemic Stroke: Causes and Mechanisms

- Ischemic Stroke: Cerebral Metabolism and Pathophysiology

- Ischemic Stroke: Pathological Brain Changes

- Ischemic Stroke: Neurological Symptoms

- Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA): Neurological Symptoms

- Diagnosis of Cerebrovascular Diseases

- Differential Diagnosis of Cerebrovascular Diseases and Stroke Mimics

- Treatment of Cerebrovascular Diseases

Cerebrovascular Diseases: Overview

Cerebrovascular diseases, encompassing conditions that affect blood flow to the brain, represent a major global health burden. In many developed countries, stroke ranks among the top causes of death, following heart disease and cancer [1]. Furthermore, stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability in adults [1]. The prevalence of cerebrovascular disease is significant, with estimates around 800 cases per 100,000 population. Approximately 5% of individuals over the age of 65 have experienced a stroke [1, 2 - Note: Specific prevalence figures vary].

The term "cerebrovascular disease" broadly includes [1]:

- Ischemic Stroke: Caused by blockage of a brain artery (approx. 85% of all strokes).

- Hemorrhagic Stroke: Caused by rupture of a brain artery, leading to intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

- Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA): Temporary stroke symptoms without permanent brain damage (often a warning sign).

- Other conditions like cerebral venous thrombosis, vascular malformations, and vasculitis.

Ischemic Stroke: Causes and Mechanisms

Ischemic stroke, also known as cerebral infarction, occurs when blood flow to a part of the brain is interrupted, leading to tissue damage due to lack of oxygen and nutrients [1]. Typically, one or more cerebral blood vessels are involved, such as the carotid or vertebral arteries or their intracranial branches [1].

The underlying pathological process can originate either within the brain's vasculature or systemically [1, 4]:

- Intrinsic Vessel Disease: Direct damage or narrowing of a cerebral artery due to:

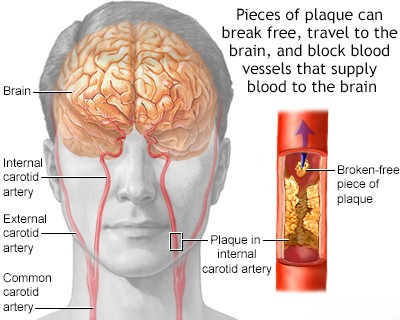

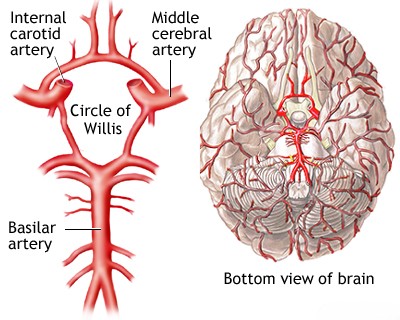

- Atherosclerosis: Buildup of fatty plaques, the most common cause, especially in large arteries (e.g., carotid bifurcation, middle cerebral artery, basilar artery).

- Small Vessel Disease (Lacunar Stroke): Damage to small penetrating arteries deep within the brain (e.g., lipohyalinosis, microatheroma), often related to hypertension and diabetes.

- Arterial Dissection: Tear in the vessel wall (e.g., carotid or vertebral artery), often spontaneous or traumatic.

- Vasculitis: Inflammation of blood vessels.

- Other Vasculopathies: Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), Moyamoya disease, radiation-induced vasculopathy, amyloid angiopathy.

- Congenital anomalies or aneurysms (though rupture causes hemorrhagic stroke, unruptured aneurysms can rarely cause ischemia via thrombosis/embolism).

- Remote Source / Systemic Issues: Blockage originating outside the affected brain artery or due to systemic problems:

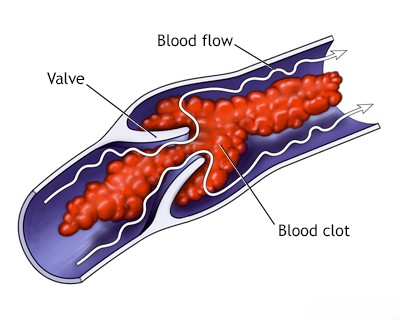

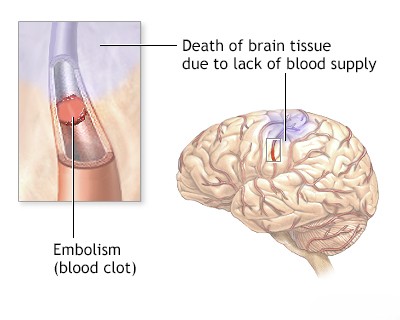

- Embolism: A clot or debris travels through the bloodstream and lodges in a cerebral artery. Sources include:

- Cardioembolism: From the heart (e.g., atrial fibrillation, valvular disease, recent myocardial infarction, intracardiac shunt like Patent Foramen Ovale [PFO]).

- Artery-to-Artery Embolism: From proximal atherosclerotic plaques (e.g., carotid artery, aortic arch).

- Other emboli: Fat, air, tumor, septic emboli (rare).

- Systemic Hypoperfusion: Generalized reduction in blood flow (e.g., due to cardiac arrest, severe hypotension, shock) causing watershed infarcts in border zones between major arterial territories.

- Hematologic Disorders: Conditions increasing blood viscosity or coagulability (e.g., polycythemia, sickle cell disease, thrombophilias).

- Embolism: A clot or debris travels through the bloodstream and lodges in a cerebral artery. Sources include:

Underlying vascular disease may remain asymptomatic until it causes a critical reduction in blood flow (stenosis leading to hypoperfusion), facilitates local clot formation (thrombosis), serves as a source for emboli, or leads to vessel rupture (hemorrhagic stroke) [1].

Stroke is the clinical manifestation resulting from these vascular events [1]. Ischemia and subsequent infarction (tissue death) occur when vessel lumen obstruction by thrombus or embolus drastically reduces or stops blood flow [1, 5]. Hemorrhagic stroke results from vessel rupture [1].

Other neurological symptoms can arise secondary to vascular issues, such as cranial nerve compression by an enlarged artery or aneurysm, vascular headaches (migraine, arteritis), or symptoms related to cerebral venous thrombosis or elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) [1].

Prevalence of Ischemic Stroke Mechanisms (Illustrative, varies by study/population) [1, 4]:

| Stroke Mechanism/Subtype | Prevalence in Younger Adults (e.g., 18-50 yrs) | Prevalence in Older Adults (e.g., >65 yrs) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardioembolism | ~20-30% | ~20-30% |

| Large Artery Atherosclerosis | ~5-10% | ~20-25% |

| Small Vessel Occlusion (Lacunar) | ~10-15% | ~20-25% |

| Other Determined Etiology (e.g., dissection, vasculitis, hematologic, specific genetic) |

~20-30% | ~5% |

| Undetermined Etiology (Cryptogenic) | ~25-35% | ~25-35% |

Ischemic Stroke: Cerebral Metabolism and Pathophysiology

The brain is highly dependent on a continuous supply of oxygen and glucose delivered by blood flow for its normal function [5]. Neurons have very limited energy reserves [5].

- Complete cessation of blood flow (e.g., cardiac arrest) leads to loss of consciousness within seconds (~10 sec) and irreversible neuronal death (infarction) within minutes (~3-5 min) under normal conditions [1, 5].

- However, if blood flow is significantly reduced but not completely stopped (ischemia), brain tissue can remain viable for a longer period before infarction occurs [5]. This state of dysfunctional but potentially salvageable tissue surrounding the core of irreversible infarction is known as the ischemic penumbra [5].

The existence of the penumbra forms the basis for acute stroke therapies aimed at restoring blood flow (reperfusion) as quickly as possible [5]. Neurons in the penumbra are functionally impaired but structurally intact [5]. If blood flow is restored within a critical time window (hours), these cells can recover, limiting the final infarct size and improving clinical outcome [5]. If ischemia persists, the penumbra progressively converts into infarcted tissue [5].

The "ischemic cascade" involves a complex series of events triggered by energy failure, including ion pump failure, release of excitatory neurotransmitters (excitotoxicity), calcium influx, inflammation, free radical production, and ultimately, cell death pathways (necrosis and apoptosis) [5]. Once infarction occurs, cell membranes lose integrity, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) breaks down (leading to vasogenic edema), and cellular metabolism ceases [5].

Ischemic Stroke: Pathological Brain Changes

The appearance of an ischemic infarct evolves over time [6]:

- Acute Stage (hours to days): Initially, the infarcted area may appear grossly normal or slightly pale and swollen (cytotoxic edema). Neurons begin to show microscopic changes (e.g., eosinophilic cytoplasm, pyknotic nuclei).

- Subacute Stage (days to weeks): The infarct becomes more clearly demarcated, often appearing pale and soft (liquefactive necrosis). Inflammatory cells (neutrophils, then macrophages) infiltrate the area to clear debris. Vasogenic edema, resulting from BBB breakdown, may peak around 3-5 days, potentially causing significant mass effect and herniation.

- Hemorrhagic Transformation: Within hours to days, especially after reperfusion (spontaneous or therapeutic), bleeding can occur into the infarcted tissue. This can range from small petechial hemorrhages to larger confluent hematomas. It is thought to result from damage to vessel walls within the ischemic zone, which become leaky upon restoration of blood flow. Embolic strokes are more prone to hemorrhagic transformation than thrombotic strokes.

- Chronic Stage (weeks to months/years): The necrotic tissue is gradually removed by macrophages, leaving behind a cystic cavity filled with CSF and surrounded by a glial scar (gliosis).

Accurate diagnosis of the stroke type (ischemic vs. hemorrhagic) and localization is crucial for appropriate treatment [7]. Determining the underlying vascular pathology (e.g., stenosis, occlusion site, dissection) and assessing collateral circulation are also vital [7].

Treatment strategies aim to [7]:

- Prevent Primary Stroke: By managing modifiable risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation).

- Treat Acute Stroke: Primarily by restoring blood flow in ischemic stroke (thrombolysis, thrombectomy) as quickly as possible ("time is brain"), or managing bleeding and pressure in hemorrhagic stroke.

- Prevent Secondary Brain Injury: By managing complications like cerebral edema, seizures, infections, and maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion pressure.

- Prevent Recurrent Stroke (Secondary Prevention): By addressing the underlying cause (e.g., antiplatelets for atherosclerosis, anticoagulation for AFib, carotid endarterectomy/stenting for severe stenosis) and continuing risk factor management.

- Promote Recovery: Through rehabilitation therapies.

Despite advances, many aspects of stroke treatment remain challenging, and evidence for some interventions is still evolving [7]. Modern management relies heavily on rapid clinical assessment and advanced neuroimaging, such as MR angiography (MRA) and CT angiography (CTA), to guide therapy [7, 8].

Ischemic Stroke: Neurological Symptoms

The specific neurological symptoms of an ischemic stroke depend entirely on the location and size of the brain area affected by the lack of blood flow [1]. The onset is typically sudden [1].

Recognizing stroke symptoms quickly is critical. The **FAST** acronym is a widely used tool [9]:

- **F**ace Drooping: Does one side of the face droop or feel numb? Ask the person to smile. Is the smile uneven?

- **A**rm Weakness: Is one arm weak or numb? Ask the person to raise both arms. Does one arm drift downward?

- **S**peech Difficulty: Is speech slurred? Is the person unable to speak or hard to understand? Ask the person to repeat a simple sentence.

- **T**ime to call emergency services (e.g., 911, 112): If someone shows any of these symptoms, even if they go away, call for help immediately and note the time symptoms first appeared.

Specific symptoms often correlate with the vascular territory involved [1]:

- Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) Territory (Most Common): Contralateral hemiparesis (weakness) and hemisensory loss (often arm and face > leg), contralateral homonymous hemianopia (visual field defect), gaze preference towards the side of the lesion. If the dominant hemisphere (usually left) is affected, aphasia (language disturbance – expressive, receptive, or global) occurs. If the non-dominant hemisphere is affected, neglect (inattention to the contralateral side of space), anosognosia (unawareness of deficit), and spatial disorientation may occur.

- Anterior Cerebral Artery (ACA) Territory: Contralateral leg > arm weakness and sensory loss, grasp reflex, frontal lobe signs (e.g., impaired judgment, abulia [lack of motivation]), urinary incontinence.

- Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA) Territory: Contralateral homonymous hemianopia is classic. Other signs can include contralateral sensory loss, memory impairment (if thalamus or temporal lobe involved), alexia without agraphia (if dominant occipital lobe/splenium involved), visual agnosia, or cortical blindness (if bilateral).

- Vertebrobasilar Territory (Brainstem/Cerebellum - see previous sections): Diverse symptoms including vertigo, dizziness, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, crossed sensory/motor signs (e.g., ipsilateral face, contralateral body), altered consciousness, quadriplegia ('locked-in syndrome' with severe pontine infarct). Specific syndromes like Wallenberg (lateral medulla) are characteristic.

- Lacunar Strokes (Small Penetrating Arteries): Often cause pure motor hemiparesis, pure sensory stroke, sensorimotor stroke, ataxic hemiparesis, or dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome, typically without cortical signs like aphasia or neglect.

The pattern of symptom evolution can provide clues: sudden maximal deficit often suggests embolism, while a stuttering or fluctuating course might suggest thrombosis or hemodynamic insufficiency [1]. However, these patterns are not entirely reliable. A sudden deep coma could result from basilar artery embolism or a large hemorrhagic stroke [1].

Obtaining an accurate history is crucial but can be difficult if the patient has cognitive impairment (e.g., aphasia, neglect, confusion) or if witnesses are unavailable [1]. Collateral circulation significantly influences the final extent of infarction and thus the severity of symptoms [1, 10]. Extensive collaterals (e.g., via the Circle of Willis or leptomeningeal anastomoses) can sometimes allow complete occlusion of a major artery with minimal or no symptoms, while poor collaterals can lead to large infarcts even with distal branch occlusions [1, 10].

"Stroke-in-evolution" or "progressive stroke" refers to neurological deficits that worsen or fluctuate after onset [1]. This may be due to thrombus propagation, worsening edema, secondary hemorrhage, or systemic factors like hypotension [1]. However, recurrent embolism or hemodynamic instability related to critical stenosis are also common causes [1].

The presence of certain risk factors increases suspicion for specific stroke mechanisms [1]. Atherosclerotic risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hyperlipidemia) suggest large artery disease or lacunar stroke [1]. Atrial fibrillation strongly suggests cardioembolism [1, 4]. Severe hypertension is a major risk factor for both ischemic (lacunar, large vessel) and hemorrhagic (deep intracerebral) stroke [1].

Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA): Neurological Symptoms

A Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) is classically defined as a transient episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischemia, without acute infarction (tissue death) [11]. Traditionally, a 24-hour time limit was used, but the modern definition emphasizes the absence of tissue injury [11]. Many TIAs last only minutes, and symptoms resolving within an hour are highly suggestive [11]. However, even brief episodes can sometimes show small infarcts on sensitive MRI sequences (DWI) [11].

TIAs are critical warning signs of an impending stroke [11]. The risk of stroke is very high in the hours and days following a TIA, necessitating urgent evaluation and treatment [11].

TIA symptoms are identical to stroke symptoms but are temporary [11]. The specific symptoms indicate the affected vascular territory [1, 11]:

- Carotid Territory (Anterior Circulation): Transient monocular blindness (amaurosis fugax), contralateral weakness or numbness (face/arm/leg), aphasia (if dominant hemisphere).

- Vertebrobasilar Territory (Posterior Circulation): Dizziness/vertigo, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, bilateral or alternating weakness/numbness, bilateral visual loss.

- Lacunar TIA: Transient pure motor, pure sensory, or sensorimotor symptoms, or dysarthria-clumsy hand, without cortical signs.

The pattern of TIAs can offer clues to the underlying mechanism [1]:

- Multiple, brief (<15 min), stereotyped (identical) episodes: Often suggest hemodynamic insufficiency due to high-grade stenosis ("low flow" TIA).

- Single, longer episode, or variable symptoms: More suggestive of an embolic source (artery-to-artery or cardioembolic).

Just like stroke, a TIA is a clinical syndrome requiring investigation to determine the underlying cause (e.g., carotid stenosis, atrial fibrillation, small vessel disease) to guide appropriate secondary prevention [11].

Diagnosis of Cerebrovascular Diseases

The diagnostic workup for suspected ischemic stroke, TIA, or chronic cerebral ischemia includes [1, 7, 8]:

- A thorough neurological examination.

- Neuroimaging: Primarily Non-Contrast CT Head (to exclude hemorrhage acutely) followed by Brain MRI (including DWI) to confirm ischemia, assess infarct size/location, and look for chronic changes.

- Vascular Imaging: To identify the cause (stenosis, occlusion, dissection, source of embolism). Includes Carotid/Vertebral Doppler Ultrasound, CTA, MRA, or sometimes DSA.

- Cardiac Evaluation: ECG, potentially prolonged cardiac monitoring (Holter, event monitor), and Echocardiogram (TTE/TEE) to screen for cardioembolic sources (especially AFib, valve disease, thrombus).

- Blood Tests: Including CBC, metabolic panel, lipids, HbA1c, coagulation studies, +/- hypercoagulable workup in selected patients.

- Other tests like REG or EEG may be considered in specific contexts but are not routine for primary diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis of Cerebrovascular Diseases and Stroke Mimics

Diagnosing vascular brain lesions relies on recognizing characteristic stroke/TIA syndromes [1]. However, other conditions can mimic these presentations ("stroke mimics") [12]. Key distinguishing features often involve the temporal profile (onset, duration, evolution), associated symptoms, and findings on neurological examination and diagnostic tests.

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Focal Neurological Deficits ("Stroke Mimics") [1, 12]

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ischemic Stroke / TIA | Sudden onset focal neurological deficit corresponding to vascular territory. Risk factors often present. TIA resolves completely (<24h, often <1h). | CT head excludes hemorrhage. MRI (DWI) confirms ischemia early. Vascular imaging identifies cause. |

| Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH) | Sudden onset focal deficit, often with headache, vomiting, decreased consciousness, severe hypertension. | Non-contrast CT head shows hemorrhage. |

| Seizure with Todd's Paralysis | Post-ictal focal weakness mimicking stroke. History of seizure. Transient (resolves <48h). | History. EEG may show abnormalities. Imaging usually normal unless underlying lesion. Transient nature. |

| Migraine with Aura (esp. Hemiplegic) | Transient neurological symptoms (often spreading gradually) followed by/accompanying headache. History of similar episodes. Full recovery. | Clinical diagnosis. Normal exam between attacks. Imaging usually normal. |

| Hypoglycemia | Can cause focal neurological deficits, confusion, seizures. History of diabetes relevant. | Low blood glucose. Symptoms improve with glucose. |

| Brain Tumor | Can present acutely (hemorrhage/seizure) causing focal signs, but often progressive symptoms precede. | MRI with contrast shows mass lesion. |

| Subdural Hematoma | Can cause focal signs due to compression. Headache, altered mental status. History of trauma (may be minor). | CT/MRI shows subdural collection. |

| Metabolic Encephalopathy / Systemic Infection | Diffuse dysfunction (confusion, lethargy). Focal signs uncommon unless superimposed issue. Identifiable systemic cause. | Specific lab abnormalities. Imaging non-specific. Signs of infection. |

| Multiple Sclerosis Relapse | Acute/subacute onset focal deficits. History of prior episodes possible. | MRI shows demyelinating lesions. |

| Peripheral Vertigo | Acute vertigo, nausea. No other brainstem signs usually. | Clinical exam (HINTS). Normal brain imaging. |

| Syncope | Brief LOC due to global hypoperfusion. Rapid recovery. | History. Cardiac evaluation. Normal exam post-event. |

| Functional Neurological Disorder | Symptoms inconsistent with organic patterns. | Diagnosis of exclusion. Normal imaging/labs. |

Accurate history taking, careful neurological examination, and appropriate, timely neuroimaging are key to distinguishing stroke from its mimics [1, 12]. Conditions like chronic VBI, with intermittent symptoms like dizziness or gait instability, also require differentiation from TIA, peripheral vestibular disorders, or other neurological conditions [1].

Treatment of Ischemic Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA), and Cerebral Ischemia

Treatment strategies are tailored to the specific diagnosis (stroke vs TIA, ischemic vs hemorrhagic), the underlying cause, the time since onset, and patient factors [1, 7]. Key approaches include:

- Acute Ischemic Stroke:

- Reperfusion Therapy: Intravenous thrombolysis (tPA/Alteplase) if within 4.5 hours and eligible [7, 13]; Mechanical thrombectomy for large vessel occlusion up to 24 hours in selected patients [7, 14].

- Supportive Care: Blood pressure management, glucose control, fever management, DVT prophylaxis, aspiration precautions [7].

- Antiplatelet Therapy: Usually started after 24 hours post-thrombolysis or earlier if no thrombolysis given [7].

- Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA):

- Urgent evaluation to determine cause and stroke risk (e.g., ABCD² score) [11].

- Antiplatelet Therapy: Often dual antiplatelets (Aspirin + Clopidogrel) for a short period (21-90 days) followed by monotherapy [15].

- Risk Factor Management: Aggressive control of BP, lipids, diabetes; smoking cessation [16].

- Addressing the Cause: Anticoagulation for AFib [17], carotid endarterectomy/stenting for symptomatic high-grade stenosis [18].

- Chronic Cerebral Ischemia / Secondary Prevention [1, 16]:

- Antiplatelet agents.

- High-intensity statin therapy.

- Aggressive risk factor management (BP, diabetes, lipids, smoking, lifestyle).

- Specific interventions based on cause (e.g., carotid surgery/stenting).

- Rehabilitation: Physiotherapy, Occupational therapy, Speech therapy.

- Other modalities: Massage, Medical gymnastics, Acupuncture may be used adjunctively for symptom management or during rehabilitation.

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases.

- Feigin VL, Roth GA, Naghavi M, et al. Global Burden of Stroke and Risk Factors in 188 Countries, during 1990-2013. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 14;375(2):198.

- Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, Hansson GK, Deanfield J, Bittencourt MS, et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019 Aug 29;5(1):56.

- Grotta JC, Albers GW, Broderick JP, et al. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2021. Chapter on Mechanisms of Ischemic Stroke.

- Grotta JC, Albers GW, Broderick JP, et al. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2021. Chapter on Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2020. Chapter 28: The Central Nervous System (Section on Vascular Diseases).

- Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019 Dec;50(12):e344-e418.

- Osborn AG, Hedlund GL, Salzman KL. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Stroke and Vascular Disease.

- American Stroke Association. Stroke Warning Signs and Symptoms. Available at: [Insert appropriate URL, e.g., https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-symptoms]

- Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases. 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates; 2010. Chapter 4: Blood Supply, Meninges, and Venous Drainage.

- Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009 Jun;40(6):2276-93.

- Caplan LR. Stroke Mimics. Semin Neurol. 2016 Apr;36(2):203-12.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al; ECASS Investigators. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359(13):1317-29.

- Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al; HERMES collaborators. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016 Apr 23;387(10029):1723-31.

- Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al; CHANCE Investigators. Clopidogrel and Aspirin in Acute Ischemic Stroke and High-Risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 4;369(1):11-9.

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014 Jul;45(7):2160-236. (Or more recent updates).

- January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2019 Jul 9;140(2):e125-e151.

- Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Stroke. 2011 Aug;42(8):e464-540. (Or more recent updates).

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis