Cerebrovascular atherosclerotic thrombosis

Cerebrovascular Atherosclerotic Thrombosis Overview

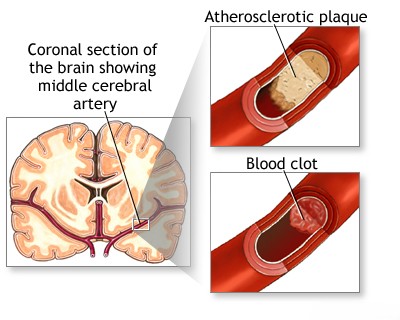

Atherosclerotic thrombosis is the most common cause of cerebral vessel thrombosis, as listed in the table below [1]. Atherosclerosis preferentially affects specific locations within extracranial and intracranial arteries. Atheromatous plaques are more likely to develop at the origins and bifurcations of large vessels, and thrombosis typically occurs where the plaque significantly narrows the artery (stenosis) [2].

The precise mechanisms underlying thrombosis development are complex. Atheromatous lesions develop within the intima (inner layer) and can extend into the tunica media (middle layer), potentially disrupting the vessel wall. Plaques consist of hyalinized connective tissue, fibroblasts, macrophages, smooth muscle cells, and interspersed cholesterol crystals [3].

Thrombosis is believed to initiate when the atherosclerotic process damages the endothelium (the inner lining of the vessel), leading to platelet aggregation and the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) on the vessel wall [4].

Occasionally, blood flow can dissect underneath the atheromatous plaque, lifting it into the vessel lumen. This dissection can create ulcerations on the plaque surface, which become sites for thrombus formation. Less frequently, hemorrhage within the plaque itself (intraplaque hemorrhage) can further narrow the lumen [5].

Atheromatous narrowing often creates an hourglass-like configuration, with the stenotic (narrowed) segment typically being only 1-2 mm long. Intravascular thrombosis can develop within, proximal (before), or distal (after) to this stenotic segment. Thrombotic occlusion (complete blockage) usually occurs when the atherosclerotic plaque severely obstructs blood flow [6].

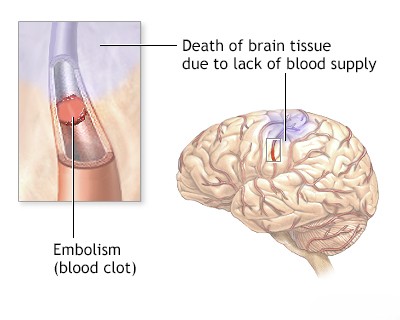

Predicting the extent of brain damage resulting from atherosclerotic thrombosis is challenging. The clinical outcome depends on factors such as the availability of collateral blood flow (alternative blood supply routes), the speed at which the thrombotic occlusion develops, and the potential for fragments of the thrombus to break off and travel downstream (distal embolization) [8].

The clinical presentation of cerebral artery obstruction varies significantly among patients, and most syndromes represent partial deficits rather than complete ones. The described symptoms are characteristic of ischemic events (lack of blood flow) within specific arterial territories. However, similar presentations can also occur following embolization from another source (like the heart). In some instances, intracerebral hemorrhage (bleeding within the brain) in a vascular territory can mimic these ischemic symptoms [9].

Causes of Cerebrovascular Occlusion (Including Thrombosis) [11]

| Cause | Features |

|---|---|

| Cerebral atherosclerosis | |

| Thrombophlebitis of cerebral vessels |

|

| Arteritis of cerebral vessels |

|

| Hematological disorders |

|

| Injury of the carotid artery | |

| Dissecting aortic aneurysm | |

| Systemic hypotension |

|

| Complications of arteriography (angiography with contrast) | |

| Migraine aura with persistent deficits | |

| Cerebral herniation syndromes (brainstem, hemispheres, or cerebellum): | |

|

|

| Hypoxia | |

| Various causes of thrombosis of cerebral vessels |

|

| Unexplained causes of thrombosis of cerebral vessels | For example, in childhood |

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Focal Neurological Deficits (Stroke Symptoms) [12]

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ischemic Stroke (Thrombotic / Embolic) | Sudden onset focal neurological deficit corresponding to vascular territory. Risk factors (atherosclerosis, AFib, HTN, DM). TIA may precede thrombotic stroke. | Non-contrast CT head initially to rule out hemorrhage. MRI (esp. DWI) confirms ischemia early. CTA/MRA identifies vessel occlusion/stenosis. Cardiac workup (ECG, Echo) for embolism source. |

| Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH) | Sudden onset focal neurological deficit. Often associated with headache, vomiting, decreased consciousness, severely elevated BP. | Non-contrast CT head definitively shows hemorrhage. MRI can provide more detail later. Control BP. |

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) | Sudden severe "thunderclap" headache. Often decreased consciousness, nausea/vomiting, neck stiffness. Focal signs less common initially unless associated ICH or vasospasm. | Non-contrast CT head shows subarachnoid blood. LP if CT negative but suspicion high. CTA/DSA identifies aneurysm. |

| Seizure with Todd's Paralysis | Post-ictal (after seizure) focal weakness or paralysis mimicking stroke. History of seizure (witnessed or suspected). Usually resolves within minutes to 48 hours. | History of seizure event. EEG may show post-ictal slowing or epileptiform activity. Brain imaging often normal or shows underlying cause of seizure. Transient nature. |

| Migraine with Aura (esp. Hemiplegic) | Transient neurological symptoms (visual, sensory, motor - hemiparesis) precede or accompany migraine headache. Often history of similar episodes. Symptoms typically spread gradually and resolve completely. | Clinical diagnosis based on characteristic history and pattern. Neurological exam normal between attacks. Imaging usually normal (to exclude stroke). |

| Hypoglycemia | Can present with focal neurological deficits mimicking stroke, seizures, or altered mental status. History of diabetes (esp. on insulin/sulfonylureas). | Low blood glucose level on fingerstick/lab test. Symptoms resolve rapidly with glucose administration. |

| Brain Tumor | Usually progressive focal deficits, headache, seizures over weeks/months. Can present acutely due to hemorrhage into tumor or seizure. | MRI with contrast shows mass lesion. CT may show mass +/- hemorrhage. |

| Brain Abscess / Infection | Focal deficits, headache, fever, seizures. Usually subacute onset. History of infection source (sinus, ear, dental, endocarditis). | MRI shows ring-enhancing lesion with central restricted diffusion. CT less sensitive. Elevated inflammatory markers (WBC, CRP). LP may show infection (if safe). |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Relapse | Acute/subacute onset of focal neurological deficits (optic neuritis, sensory changes, weakness, ataxia). Typically younger adults. History of prior neurological episodes possible. | MRI shows characteristic demyelinating lesions (T2/FLAIR hyperintense) in typical locations, +/- contrast enhancement in active lesions. Evoked potentials may be abnormal. |

| Functional Neurological Disorder (Conversion Disorder) | Neurological symptoms (weakness, sensory loss, tremor, gait disturbance) inconsistent with known neurological pathways. Often associated with psychological stressors. Positive clinical signs (e.g., Hoover's sign). | Diagnosis of exclusion based on inconsistency of signs/symptoms with organic disease after thorough workup. Normal imaging and labs. |

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2020. Chapter 11: Blood Vessels.

- Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, Hansson GK, Deanfield J, Bittencourt MS, et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019 Aug 29;5(1):56.

- Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011 Jan;42(1):227-76. (Or relevant section in Adams/Victor or Grotta).

- Grotta JC, Albers GW, Broderick JP, et al. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2021. Chapter on Atherosclerosis and Stroke.

- Caplan LR. Caplan's Stroke: A Clinical Approach. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2016. Chapter on Large Artery Atherosclerosis.

- Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Stroke. 2011 Aug;42(8):e464-540..

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases.

- Caplan LR. Caplan's Stroke: A Clinical Approach. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2016. Chapter on Clinical Manifestations of Stroke (General Principles).

- Grotta JC, Albers GW, Broderick JP, et al. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2021. Chapter on Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke.

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases. (Also see Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, Chapter on Stroke).

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases, section on Differential Diagnosis.

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 27: Coma and Related Disorders of Consciousness, section on Herniation Syndromes.

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis