Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

Cerebral Arteritis (CNS Vasculitis): Overview

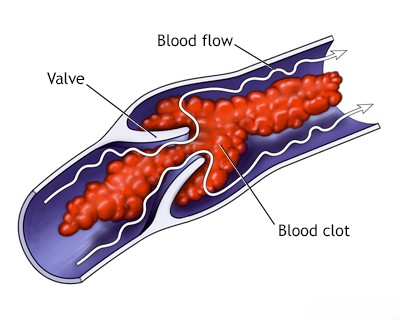

Cerebral Arteritis, more commonly known as Central Nervous System (CNS) Vasculitis, is a serious condition characterized by inflammation of the walls of blood vessels (arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, or veins) within the brain, spinal cord, and sometimes the meninges [1, 2]. This inflammation can damage the vessel walls, leading to:

- Narrowing (stenosis) or blockage (occlusion) of the vessel lumen, causing ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).

- Weakening of the vessel wall, potentially leading to aneurysm formation and hemorrhagic stroke (intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage).

- Leakage from inflamed vessels contributing to brain edema or inflammation.

CNS vasculitis is relatively rare but can cause significant neurological morbidity and mortality if not diagnosed and treated promptly [1, 2].

Causes and Classification

CNS vasculitis is broadly classified into two main categories [1, 2]:

- Primary Angiitis of the CNS (PACNS): This is vasculitis confined solely to the CNS, with no evidence of inflammation or vasculitis elsewhere in the body [1, 2]. Its cause is unknown (idiopathic), although an autoimmune mechanism is suspected [2]. Pathologically, it often shows granulomatous inflammation, but other patterns exist [1].

- Secondary CNS Vasculitis: This occurs when CNS blood vessel inflammation is part of, or a complication of, another underlying condition [1, 2]. Causes include:

- Systemic Autoimmune / Inflammatory Diseases: Vasculitis can affect the brain as part of systemic conditions such as [1, 2]:

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Sjögren's Syndrome

- Sarcoidosis

- Behçet's Disease

- ANCA-associated vasculitides (Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis [GPA], Microscopic Polyangiitis [MPA], Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis [EGPA])

- Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) / Temporal Arteritis: Primarily affects large extracranial arteries but can involve intracranial vessels, including vertebral/basilar arteries.

- Polyarteritis Nodosa (PAN)

- Infections: Various infectious agents can directly invade vessel walls or trigger an inflammatory response leading to vasculitis [1, 2]:

- Viral: Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) is a well-known cause (VZV vasculopathy), often following shingles or chickenpox (sometimes years later). HIV, Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can also be implicated.

- Bacterial: Complications of bacterial meningitis (e.g., Tuberculosis, Syphilis [historically common, now less so due to antibiotics], Lyme disease, bacterial endocarditis leading to septic emboli/mycotic aneurysms/arteritis). Pathogens like Streptococcus, Pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae were historically associated with meningitis-related vascular complications.

- Fungal: Especially in immunocompromised patients (e.g., Aspergillus, Mucor). Mucormycosis invading from sinuses can directly affect adjacent vessels like the internal carotid artery.

- Parasitic: Less common causes like neurocysticercosis, toxoplasmosis, malaria (cerebral malaria involves capillary plugging more than frank vasculitis), schistosomiasis, trichinosis (neurological symptoms often embolic/inflammatory rather than true vasculitis).

- Drug-Induced / Toxin-Related: Certain medications or illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines, phenylpropanolamine) have been associated with CNS vasculitis or vasculopathy [1].

- Neoplasm-Associated: Rarely, vasculitis can be a paraneoplastic phenomenon related to underlying cancer [1].

- Systemic Autoimmune / Inflammatory Diseases: Vasculitis can affect the brain as part of systemic conditions such as [1, 2]:

Some conditions like Moyamoya disease or reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) involve narrowing of cerebral arteries but are generally considered non-inflammatory vasculopathies, though inflammation can sometimes play a role or coexist [1].

Clinical Presentation

CNS vasculitis is often called the "great mimicker" because its symptoms are highly variable and non-specific, depending on the size, location, and number of vessels involved, as well as the tempo of inflammation [1, 2]. Presentation can be acute, subacute, or chronic [2].

Common manifestations include [1, 2]:

- Headache: Often severe, persistent, or diffuse; may be the initial symptom.

- Focal Neurological Deficits: Presenting as stroke or TIA (ischemic or hemorrhagic). Weakness (hemiparesis), numbness (hemisensory loss), visual disturbances (hemianopia, diplopia), speech problems (aphasia, dysarthria), ataxia. Multiple strokes occurring over time or in different vascular territories should raise suspicion.

- Cognitive Impairment / Encephalopathy: Ranging from mild confusion, memory problems, and personality changes to severe delirium or coma. Can be progressive.

- Seizures: Focal or generalized.

- Myelopathy: Spinal cord involvement can cause weakness, sensory level, and bowel/bladder dysfunction.

- Cranial Neuropathies: Less common, but can occur.

- Systemic Symptoms (in Secondary Vasculitis): Fever, malaise, weight loss, rash, arthritis, or symptoms related to the specific underlying systemic disease. These are typically *absent* in PACNS.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing CNS vasculitis is challenging and requires excluding other conditions that can cause similar neurological symptoms and imaging findings (e.g., infection, embolism, RCVS, genetic vasculopathies, demyelinating disease, neoplasm) [1, 2].

Differential Diagnosis of CNS Vasculitis [1, 2, 3]

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| CNS Vasculitis (Primary or Secondary) | Headache, multifocal strokes (ischemic/hemorrhagic) over time, cognitive decline, seizures. Secondary: systemic symptoms present. PACNS: isolated to CNS. | MRI: Multiple infarcts/hemorrhages/enhancing lesions. Angiography (DSA/CTA/MRA): Segmental narrowing ("beading"), stenosis, occlusion (often non-specific). CSF: Mild inflammation (pleocytosis, high protein). Brain biopsy confirms (gold standard). Elevated ESR/CRP (esp. secondary). |

| Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS) | Recurrent "thunderclap" headaches over days/weeks. Often triggered (postpartum, vasoactive drugs). Transient focal deficits possible. No systemic inflammation. | Angiography: Multifocal segmental vasoconstriction (similar to vasculitis). CSF normal. Vasoconstriction resolves spontaneously over weeks/months on follow-up imaging. MRI brain often normal or shows PRES/small infarcts. |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | Relapsing-remitting or progressive neurological deficits (optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, brainstem/cerebellar signs). Younger adults typically. | MRI: Characteristic demyelinating plaques (periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, spinal cord), often enhancing when active. CSF: Oligoclonal bands. |

| Embolic Stroke (Multiple Territories) | Multiple strokes occurring simultaneously or sequentially in different vascular territories. Requires identifying embolic source (cardiac, large artery). | MRI (DWI) shows acute infarcts in multiple territories. Cardiac workup (ECG, Echo, Holter). Vascular imaging of neck/aorta. Angiography of brain vessels usually normal (unless embolus visible). |

| Infectious Meningitis / Encephalitis | Fever, headache, altered mental status, neck stiffness. May have focal deficits or infarcts secondary to infectious vasculitis/vasospasm. | CSF analysis diagnostic (pleocytosis, protein/glucose changes, specific pathogen ID). MRI may show meningeal enhancement or parenchymal changes. |

| CADASIL / Other Genetic Vasculopathies | Inherited conditions causing small vessel disease. Recurrent strokes, migraine with aura, cognitive decline, mood disorders often starting in mid-adulthood. Family history. | MRI shows characteristic confluent white matter hyperintensities (esp. temporal poles in CADASIL), lacunar infarcts. Genetic testing confirms (e.g., NOTCH3 for CADASIL). Skin biopsy (CADASIL). |

| Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) | Hypercoagulable state causing arterial/venous thrombosis. Recurrent strokes, TIAs, other thrombotic events. Associated with autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE listed under Vasculitis) or primary. | MRI shows infarcts. Positive antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, anti-beta2-glycoprotein I). |

| Moyamoya Disease/Syndrome | Progressive stenosis/occlusion of distal ICAs and proximal MCAs/ACAs with development of extensive basal collateral vessels ("puff of smoke"). Causes stroke (ischemic/hemorrhagic), TIAs, headaches. | Angiography (MRA/CTA/DSA) shows characteristic findings. MRI shows infarcts/hemorrhages. |

The diagnostic workup typically involves [1, 2, 3]:

- Clinical Evaluation: Detailed history and neurological examination. Assessing for systemic signs/symptoms is crucial to differentiate primary vs. secondary forms.

- Laboratory Tests:

- Basic labs (CBC, electrolytes, renal/liver function).

- Inflammatory markers: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-reactive Protein (CRP) - may be elevated, especially in secondary vasculitis or GCA, but often normal in PACNS.

- Autoimmune screen: Antinuclear Antibody (ANA), Extractable Nuclear Antigens (ENA), Rheumatoid Factor (RF), Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (ANCA), complement levels, antiphospholipid antibodies.

- Infectious workup: Blood cultures, serologies for syphilis, HIV, Lyme, VZV, hepatitis B/C; testing based on exposure/risk factors.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis (via Lumbar Puncture): Often shows non-specific signs of inflammation: mild-moderate pleocytosis (increased white blood cells, usually lymphocytic), elevated protein. Essential to rule out infection (Gram stain, cultures, PCR for viruses like VZV/HSV). Oligoclonal bands may be present.

- Neuroimaging:

- MRI Brain: Often shows multiple ischemic infarcts of varying ages in different vascular territories (cortical and subcortical), sometimes with hemorrhage, T2/FLAIR white matter hyperintensities, or enhancing lesions. Gadolinium contrast may show leptomeningeal enhancement or vessel wall enhancement (using specific high-resolution vessel wall imaging sequences). MRI is highly sensitive for detecting brain abnormalities but findings are often non-specific for vasculitis.

- Vascular Imaging (MRA, CTA, DSA): May show characteristic abnormalities like segmental narrowing ("beading"), stenosis, occlusions, or occasionally aneurysms. However, findings can be non-specific (mimicking atherosclerosis or RCVS), and imaging may be normal, especially in small-vessel vasculitis. Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) is considered the gold standard for vessel morphology but is invasive and has risks.

MR venography showing left transverse sinus thrombosis. While vasculitis *can* affect veins/sinuses, it primarily targets arteries. Venous thrombosis is a distinct condition, sometimes triggered by infection or inflammation. - Brain and Leptomeningeal Biopsy: Considered the definitive diagnostic test, especially for suspected PACNS where other causes have been excluded [1, 2]. A biopsy demonstrating transmural inflammation of vessel walls confirms the diagnosis [1]. However, it is invasive with potential risks, and the yield can be limited by the patchy nature of the disease (sampling error) [1, 2]. Biopsy is usually targeted to an area showing abnormality on MRI [2].

Treatment Principles

Treatment aims to suppress the inflammation, prevent further vascular damage and neurological injury, and manage the underlying cause if secondary [1, 2].

- Immunosuppression (for non-infectious vasculitis): This is the mainstay of treatment for PACNS and autoimmune-related secondary CNS vasculitis [1, 2].

- High-Dose Corticosteroids: (e.g., intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisone) are typically the first-line induction therapy to quickly control inflammation.

- Cytotoxic Agents: Often added for induction in moderate-to-severe cases, especially PACNS, or as steroid-sparing maintenance therapy. Cyclophosphamide (oral or IV) is commonly used initially.

- Maintenance Therapy: After achieving remission, treatment is often transitioned to less toxic agents like azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), or methotrexate for long-term control (often 1-2 years or longer).

- Biologic Agents: Rituximab (anti-CD20 antibody) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors may be used in refractory cases or specific systemic vasculitides.

- Treatment of Underlying Cause (for Secondary Vasculitis):

- Infectious Vasculitis: Requires specific antimicrobial therapy (e.g., high-dose antivirals like acyclovir for VZV/HSV, appropriate antibiotics for bacterial/syphilis/TB, antifungals for fungal causes). Immunosuppression may sometimes be cautiously added for the inflammatory component once the infection is under control, but can be dangerous if infection is active.

- Systemic Autoimmune Disease: Treatment focuses on managing the underlying systemic condition, often involving corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants tailored to that disease.

- Supportive Care: Management of stroke complications, seizure control with anti-epileptic drugs, cognitive support, rehabilitation therapies.

- Risk Factor Management: Controlling traditional vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, etc.) remains important.

Prognosis is variable and depends on the underlying cause, severity at diagnosis, promptness of treatment, and response to therapy [1]. PACNS generally requires long-term immunosuppression to prevent relapse [2].

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases (Section on Vasculitis of the Nervous System).

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Hunder GG. Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis. Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380(9843):767-77. (Or similar comprehensive review).

- Osborn AG, Hedlund GL, Salzman KL. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Vasculitis and Inflammatory Vasculopathies.

- Fauci AS, Langford CA. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. McGraw Hill; 2018. Chapters on Vasculitis.

- Birnbaum J, Hellmann DB. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2009 Jun;66(6):704-9.

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis