Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

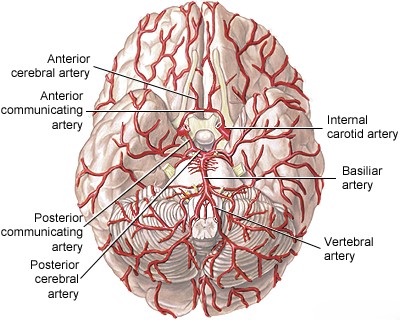

PCA Stroke: Anatomy and Pathophysiology

The Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA) is a major artery supplying the posterior regions of the brain [1, 2]. Its anatomy and the structures it supplies are key to understanding stroke symptoms.

Origin and Segments [1, 2]:

- In most individuals (~70%), both PCAs arise from the bifurcation of the basilar artery at its apex ("top of the basilar").

- In a significant minority (~20-25%), one PCA arises primarily from the ipsilateral internal carotid artery via a large posterior communicating artery (PComm), known as a "fetal PCA".

- Rarely (~5-8%), both PCAs have a fetal origin.

- The PCA is typically divided into segments:

- P1 Segment (Pre-communicating/Peduncular): From the basilar bifurcation to the junction with the PComm artery. It gives off crucial penetrating branches (thalamoperforators, posterior choroidal arteries).

- P2 Segment (Ambient): Courses around the midbrain in the ambient cistern, giving off temporal lobe branches.

- P3 Segment (Quadrigeminal): Located within the quadrigeminal cistern.

- P4 Segment (Cortical): Branches supplying the occipital and inferior/medial temporal cortex.

Supplied Structures [1, 2]:

- P1 Branches (Thalamoperforators, Posterior Choroidal): Supply critical deep structures including:

- Midbrain: Cerebral peduncles, substantia nigra, red nucleus, oculomotor nerve (CN III) nucleus/fascicles, reticular formation, superior cerebellar peduncle decussation, medial longitudinal fasciculus, medial lemniscus.

- Thalamus: Multiple nuclei (anterior, medial, posterior, ventral groups), medial and lateral geniculate bodies.

- Subthalamus: Subthalamic nucleus.

- Choroid plexus of the third and lateral ventricles.

- P2-P4 Branches (Cortical): Supply:

- Occipital Lobe: Including the primary visual cortex (calcarine cortex) and visual association areas.

- Inferior and Medial Temporal Lobe: Including the hippocampus (memory) and parahippocampal gyrus.

- Splenium of the Corpus Callosum.

- Posterior Thalamus (via distal branches).

Pathophysiology of Occlusion [1, 3]:

- Embolism: This is the most common mechanism, especially for distal PCA territory infarcts. Emboli often originate from the heart (cardioembolism) or proximal vertebrobasilar atherosclerosis (artery-to-artery embolism). Emboli lodging at the basilar bifurcation can affect both PCAs and superior cerebellar arteries ("Top of the Basilar" syndrome).

- Atherothrombosis: Atherosclerotic plaque within the PCA itself (often P1 or P2 segments) or the distal basilar artery can lead to local thrombosis or artery-to-artery embolism into distal branches. This is less common than embolism as the primary PCA stroke cause.

- Less Common Causes: Dissection, vasculitis, hypercoagulable states.

Occlusion of the P1 segment or its penetrating branches typically causes "central" infarcts affecting the midbrain, thalamus, and subthalamus. Occlusion of the P2 segment or beyond primarily causes "peripheral" or cortical infarcts affecting the occipital and temporal lobes [1].

PCA Stroke: Clinical Symptoms Overview

The clinical presentation of PCA stroke varies greatly depending on the location of the occlusion (proximal vs. distal), the specific branches involved, whether the occlusion is unilateral or bilateral, and the adequacy of collateral circulation (e.g., via the PComm artery) [1, 3].

Symptoms generally fall into two broad categories based on the territory affected [1, 3]:

- Central Syndromes: Affecting deep structures (thalamus, midbrain, subthalamus) due to occlusion of P1 or its penetrating branches.

- Peripheral/Cortical Syndromes: Affecting the occipital and temporal lobes due to occlusion of P2 or its cortical branches.

"Top of the Basilar" syndrome, often caused by embolism to the basilar bifurcation, frequently involves bilateral PCA territories and potentially superior cerebellar artery territories, leading to a combination of central and peripheral signs, often with significant disturbance of consciousness and eye movements [1, 3].

Proximal/Central PCA Syndromes (P1 Segment / Penetrating Branches)

Occlusion here affects deep structures, leading to [1, 3]:

- Midbrain Syndromes:

- Weber's Syndrome: Ipsilateral CN III palsy + contralateral hemiplegia (infarction of cerebral peduncle and CN III fascicles).

- Claude's Syndrome: Ipsilateral CN III palsy + contralateral ataxia (infarction involving red nucleus/dentatothalamic tract and CN III fascicles).

- Benedikt's Syndrome: Combination of CN III palsy with contralateral tremor/ataxia/hemiparesis.

- Parinaud's Syndrome (Dorsal Midbrain Syndrome): Impaired vertical gaze, pupillary abnormalities, convergence-retraction nystagmus (infarction near pretectal area/posterior commissure).

- Contralateral ataxia or tremor (rubral tremor) if dentatothalamic pathways or red nucleus affected.

- Thalamic Syndromes:

- Dejerine-Roussy Syndrome (Classic Thalamic Pain Syndrome): Initial contralateral hemisensory loss (all modalities), which may evolve over weeks/months into severe, debilitating contralateral pain (dysesthesia, allodynia, hyperpathia), often burning or aching. May have associated mild hemiparesis, choreoathetosis, or ataxia. Caused by infarction of the ventral posterolateral (VPL) / ventral posteromedial (VPM) nuclei.

- Pure sensory stroke or selective loss of certain modalities can occur depending on the specific thalamic nuclei involved.

- Disturbances of consciousness, memory (amnesia), behavior, or language (thalamic aphasia) can occur with involvement of anterior/medial thalamic nuclei or bilateral lesions.

- Subthalamic Syndromes: Infarction involving the subthalamic nucleus can cause contralateral hemiballismus (violent flinging movements).

- Artery of Percheron Occlusion: Causes bilateral paramedian thalamic +/- rostral midbrain infarction. Classic presentation includes altered mental status (ranging from hypersomnolence to coma), vertical gaze palsy, and memory impairment. Motor deficits are often absent.

Complete occlusion of the P1 segment can potentially cause extensive midbrain and thalamic infarction, possibly including contralateral hemiplegia if the cerebral peduncle is significantly involved [1]. Associated cortical PCA signs (e.g., hemianopia) may also occur if the PComm provides poor collateral flow [1].

Distal/Cortical PCA Syndromes (P2 Segment and Beyond)

Occlusion here affects the cortical surfaces supplied by the PCA [1, 3]:

- Visual Field Defects: The most common manifestation of cortical PCA stroke, due to occipital lobe infarction.

- Contralateral Homonymous Hemianopia: Loss of vision in the opposite half of the visual field in both eyes. Often spares central (macular) vision due to dual blood supply to the occipital pole (from PCA and MCA).

- Contralateral Superior Quadrantanopia: Visual loss in the upper quadrant, if infarction is limited to the inferior bank of the calcarine fissure (lingual gyrus).

- Contralateral Inferior Quadrantanopia: Visual loss in the lower quadrant, if infarction involves the superior bank of the calcarine fissure (cuneus).

- Cortical Blindness (Anton's Syndrome): Bilateral PCA occlusion causing complete blindness, often accompanied by denial of blindness (anosognosia) and confabulation. Pupillary light reflexes remain intact because the reflex pathway bypasses the occipital cortex.

- Visual Processing Deficits:

- Alexia without Agraphia: Inability to read despite preserved ability to write (dominant hemisphere lesion involving splenium of corpus callosum and left occipital lobe).

- Color Anomia/Achromatopsia: Difficulty naming colors or perceiving color.

- Visual Agnosia: Inability to recognize objects visually (prosopagnosia - inability to recognize faces, often non-dominant lesion).

- Balint's Syndrome: Bilateral parieto-occipital lesions causing simultanagnosia (inability to perceive the visual scene as a whole), optic ataxia (inability to guide hand movements using vision), and ocular apraxia (inability to direct gaze voluntarily).

- Complex visual hallucinations or distortions (palinopsia, metamorphopsia).

- Memory Impairment (Amnesia): Can occur with unilateral (especially dominant) or bilateral infarction of the medial temporal lobes (hippocampus). Often transient with unilateral lesions.

- Sensory Deficits: Contralateral hemisensory loss can occur if the posterior thalamus is involved via distal PCA branches.

- Motor Deficits: Generally absent in pure cortical PCA strokes, but mild contralateral weakness can occur if infarction extends deep to involve descending pathways.

Distinguishing these syndromes helps localize the lesion within the PCA territory [1, 3].

Summary of PCA Stroke Syndromes [1, 3]:

| Territory / Syndrome | Common Signs and Symptoms | Typical Structures Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Central Territory (P1 / Penetrating Branches) | ||

| Thalamic Syndrome (Dejerine-Roussy) | Contralateral sensory loss (all modalities), later developing chronic pain (dysesthesia). May have mild hemiparesis, choreoathetosis. | Ventral posterolateral/posteromedial (VPL/VPM) thalamic nuclei. |

| Midbrain Syndromes (Weber, Claude, Benedikt) | Ipsilateral CN III palsy combined with contralateral hemiplegia and/or ataxia/tremor. | CN III fascicles plus cerebral peduncle and/or red nucleus/dentatothalamic tract. |

| Artery of Percheron Occlusion | Altered consciousness (hypersomnolence to coma), vertical gaze palsy, memory impairment, +/- behavioral changes. | Bilateral paramedian thalami +/- rostral midbrain. |

| Peripheral Territory (P2-P4 / Cortical Branches) | ||

| Occipital Lobe Infarction | Contralateral homonymous hemianopia (often macular sparing) or quadrantanopia. | Calcarine cortex (primary visual cortex) or optic radiations. |

| Bilateral Occipital Infarction | Cortical blindness (often with denial - Anton's syndrome). Pupillary reflexes intact. | Bilateral occipital lobes. |

| Dominant Hemisphere Occipital + Splenial Lesion | Alexia without agraphia (cannot read, can write), color anomia. | Left occipital lobe and splenium of corpus callosum. |

| Medial Temporal Lobe Infarction | Memory impairment (amnesia). | Hippocampus (unilateral or bilateral). |

| Non-dominant Hemisphere Occipito-temporal Lesion | Prosopagnosia (facial recognition difficulty), topographical disorientation, visual agnosia. | Right occipital/temporal visual association cortex. |

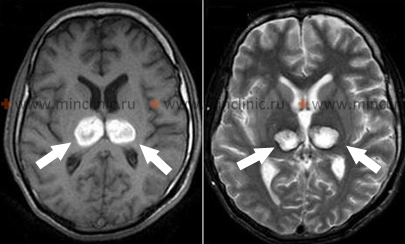

PCA Stroke: Diagnosis and Imaging

Diagnosis relies on recognizing the characteristic clinical syndromes and confirming with neuroimaging [1, 4].

- Clinical Assessment: History of symptom onset (often sudden), specific visual, sensory, motor, or cognitive deficits. Neurological exam including formal visual field testing, eye movement assessment, sensory testing, coordination, and cognitive evaluation.

- Neuroimaging:

- MRI Brain: The most sensitive modality, especially for detecting ischemia in the thalamus, midbrain, and occipital lobes. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) sequences are crucial for identifying acute infarcts within minutes to hours of onset. MRI can detect small lacunar infarcts from penetrating branch occlusion that may be missed on CT.

- CT Brain: Initial non-contrast CT is essential to rule out hemorrhage. It is less sensitive than MRI for detecting acute ischemic changes, especially in the posterior fossa or deep structures, particularly in the first 24 hours. Established infarcts appear as low-density areas later.

- Vascular Imaging (CTA, MRA, DSA): Used to identify the site of occlusion or stenosis in the PCA or vertebrobasilar system, or to detect potential embolic sources (e.g., basilar artery plaque, vertebral dissection) [1, 4]. DSA remains the gold standard for vessel detail but is invasive [4].

- Cardiac Evaluation: ECG, Holter monitoring, and echocardiography are crucial to investigate for cardioembolic sources (e.g., atrial fibrillation, valvular disease, PFO), especially given the high frequency of embolism causing PCA strokes [1, 3].

Differential Diagnosis of PCA Stroke Symptoms [1, 5]

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Investigations / Findings |

|---|---|---|

| PCA Ischemic Stroke | Sudden onset visual field defect (hemianopia/quadrantanopia), +/- sensory loss, memory issues, midbrain signs (CN III palsy, gaze palsy), thalamic pain. Cortical blindness if bilateral. | MRI (DWI) confirms acute infarct in PCA territory (occipital, temporal, thalamus, midbrain). CT excludes hemorrhage. Vascular imaging (CTA/MRA/DSA) may show occlusion/source. |

| Occipital Lobe Hemorrhage | Sudden onset visual field defect, often with headache. May have associated cognitive changes. | Non-contrast CT head shows hemorrhage in occipital lobe. Evaluate for underlying cause (CAA, AVM, tumor, anticoagulation). |

| Migraine with Visual Aura | Transient visual disturbances (scintillations, scotoma, hemianopia), often builds over minutes, typically resolves within 60 min. Usually followed by headache. History of similar episodes. | Clinical diagnosis. Normal imaging typically. |

| Occipital Lobe Seizure | Positive visual phenomena (flashing lights, colors, simple shapes), can progress to altered awareness or generalized seizure. May have post-ictal visual field deficit. | History. EEG may show occipital spikes/waves. MRI to rule out underlying lesion. |

| Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) | Headache, seizures, altered mental status, visual disturbances (including cortical blindness). Associated with severe hypertension, eclampsia, certain medications, autoimmune disease. | MRI shows characteristic bilateral vasogenic edema (T2/FLAIR hyperintense) predominantly in posterior regions (parietal/occipital). Usually reversible with treatment of underlying cause. |

| Brain Tumor (Occipital/Thalamic/Midbrain) | Often progressive symptoms (visual field defect, headache, seizures). Can present acutely with hemorrhage. | MRI with contrast shows mass lesion. |

| Toxic/Metabolic Encephalopathy | Diffuse brain dysfunction (confusion, altered LOC). Can sometimes cause visual hallucinations or cortical blindness (rarely). | Specific lab abnormalities or toxin identified. Imaging often non-specific. |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) | Rapidly progressive dementia, myoclonus, ataxia. Heidenhain variant can present primarily with visual symptoms (cortical blindness, visual field defects). | MRI (DWI) shows characteristic restricted diffusion in cortex (esp. occipital in Heidenhain) and/or basal ganglia. EEG shows periodic sharp wave complexes. CSF positive for 14-3-3 protein. |

Thus, diagnosis involves integrating clinical findings with appropriate brain and vascular imaging, and investigating potential underlying causes, particularly embolic sources [1].

PCA Stroke: Treatment Strategies

Treatment follows general principles of acute ischemic stroke management and secondary prevention [1, 6].

Acute Treatment:

- Intravenous Thrombolysis (IV tPA): Alteplase may be administered within the standard time window (typically 3-4.5 hours) to eligible patients presenting with disabling PCA stroke symptoms, provided hemorrhage is excluded on CT [6].

- Endovascular Therapy (Mechanical Thrombectomy): Primarily indicated for large vessel occlusions (LVOs) in the anterior circulation [7]. Its role in isolated PCA occlusion is less established and generally reserved for specific cases, such as occlusion of the P1 segment causing significant deficits, or as part of treating a "Top of the Basilar" occlusion involving the basilar apex and proximal PCAs [7]. Decisions are made based on time from onset, clinical severity, imaging findings (including presence of salvageable tissue on perfusion imaging), and patient factors [7].

- Supportive Care: Management in a stroke unit, monitoring vital signs, glucose control, fever management, DVT prophylaxis [6].

Secondary Prevention: Aimed at reducing the risk of recurrent stroke by addressing the underlying cause [1, 8].

- Embolic Stroke (e.g., Atrial Fibrillation): Anticoagulation (typically with DOACs or warfarin) is the mainstay.

- Atherothrombotic Stroke (less common for PCA): Antiplatelet therapy (e.g., Aspirin, Clopidogrel) is indicated.

- Statin Therapy: High-intensity statins are recommended for presumed atherosclerotic mechanisms or generally as part of comprehensive vascular risk reduction.

- Risk Factor Management: Strict control of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia; smoking cessation.

- Specific treatment for less common causes like dissection or vasculitis (e.g., anticoagulation/antiplatelets for dissection, immunosuppression for vasculitis).

Prognosis after PCA stroke varies widely [1]. Visual field defects are often permanent, though some recovery can occur [1]. Significant disability can result from thalamic pain syndrome, severe memory impairment, or profound neurological deficits associated with "Top of the Basilar" syndrome [1]. Rehabilitation (including visual therapies) plays an important role in recovery [1].

References

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, Prasad S. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. Chapter 34: Cerebrovascular Diseases (Section on Posterior Cerebral Artery Occlusion).

- Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases. 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates; 2010. Chapter 18: Brainstem III: Vascular Supply & Chapter 19: Visual System.

- Caplan LR. Caplan's Stroke: A Clinical Approach. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2016. Chapter on Posterior Circulation Stroke Syndromes.

- Osborn AG, Hedlund GL, Salzman KL. Osborn's Brain: Imaging, Pathology, and Anatomy. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017. Section on Stroke and Vascular Disease (Posterior Circulation).

- Caplan LR. Stroke Mimics. Semin Neurol. 2016 Apr;36(2):203-12.

- Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019 Dec;50(12):e344-e418.

- Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al; HERMES collaborators. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016 Apr 23;387(10029):1723-31. (Discusses LVO treatment, applicability to PCA varies).

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014 Jul;45(7):2160-236. (Or more recent updates).

See also

- Ischemic stroke, cerebral ischemia

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) with vertigo symptom

- Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

- Dizziness, stuffiness in ear and tinnitus

- Ischemic brain disease:

- Atherosclerotic thrombosis

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of internal carotid artery

- Asymptomatic carotid bifurcation stenosis with noise

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebrobasilar and posterior cerebral arteries

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of posterior cerebral artery

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICA)

- Atherothrombotic occlusion of basilar artery

- Small-vessel stroke (lacunar infarction)

- Other causes of ischemic stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Cerebral embolism

- Spontaneous intracranial (subarachnoid) and intracerebral hemorrhage:

- Arteriovenous malformations of the brain

- Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cerebral arteries inflammatory diseases (cerebral arteritis)

- Giant intracranial aneurysms

- Other causes of intracerebral hemorrhage

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Saccular aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mycotic intracranial aneurysms

- Repeated cerebral artery aneurysm rupture

- Communicating hydrocephalus after intracerebral hemorrhage with ruptured aneurysm

- Cerebral vasospasm

- Cerebrovascular diseases - ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA):

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis with thrombosis