Subdural brain abscess

Subdural Brain Abscess (Subdural Empyema) Overview

A subdural brain abscess, more commonly referred to as a subdural empyema or internal pachymeningitis, is a collection of pus in the subdural space — the potential space between the dura mater and the arachnoid mater [1]. This condition represents a neurosurgical emergency due to its potential for rapid spread over the brain surface and associated high morbidity and mortality if not treated promptly [2].

While considered a rare complication overall, particularly from otogenic sources, subdural empyemas typically arise from contiguous spread of infection from adjacent structures like the paranasal sinuses (sinusitis being the most common source, especially frontal sinusitis), middle ear/mastoid (otitis media/mastoiditis, predominantly chronic suppurative forms), or occasionally from meningitis, head trauma, or neurosurgical procedures [3]. Hematogenous spread from distant infection sites is less common than for intraparenchymal brain abscesses.

The infection often reaches the subdural space via thrombophlebitis (inflammation and clotting) of bridging veins that cross the subdural space from the sinuses or skull, or by direct extension through the dura mater, often following an initial epidural abscess [4]. Once in the subdural space, which lacks septations over the cerebral hemispheres, the infection can spread rapidly over the brain surface, commonly localizing over the cerebral convexities, in the interhemispheric fissure, or along the tentorium cerebelli. While most often occurring adjacent to the primary source (e.g., frontal lobe convexity in sinusitis), contralateral or multiple collections can occur, especially with hematogenous seeding.

Initially, the inflammatory process may result in a sterile subdural effusion, but this typically progresses rapidly to a purulent collection (empyema). The underlying arachnoid mater and pia mater often become inflamed (leptomeningitis), and the adjacent cerebral cortex can become irritated, edematous, or develop thrombophlebitis of cortical veins, leading to ischemia or infarction.

Significant accumulation of pus can exert mass effect, compressing the underlying brain and potentially causing midline shift or herniation. Direct erosion through the dura mater and bone back into adjacent cavities or even the skin is extremely rare.

Symptoms and Course of Subdural Empyema

Subdural empyema typically presents as an acute, rapidly progressive illness, often developing over days. The clinical presentation is often more dramatic and fulminant than that of an epidural or intraparenchymal brain abscess [5]. Key features include:

- Severe Headache: Usually generalized and intense, often the earliest symptom.

- High Fever and Chills: Systemic signs of infection are common, often preceding neurological symptoms.

- Meningeal Signs: Neck stiffness, photophobia, Kernig's/Brudzinski's signs are frequently present due to associated leptomeningeal inflammation.

- Altered Mental Status: Rapid progression from lethargy and confusion to stupor and coma is characteristic, reflecting increasing intracranial pressure (ICP), cortical irritation/inflammation, and potential ischemia.

- Focal Neurological Deficits: These are very common (present in >80% of cases [2]) due to direct cortical compression, inflammation, or associated cortical vein thrombosis leading to ischemia/infarction. Symptoms include contralateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia, focal seizures (often progressing to status epilepticus), aphasia (if dominant hemisphere involved), and visual field defects.

- Signs of Increased ICP: Papilledema may develop, along with nausea and vomiting.

- Symptoms related to Primary Source: Concurrent symptoms of sinusitis (facial pain/pressure, purulent nasal discharge) or otitis (ear pain, discharge) may be present or precede the neurological decline.

The clinical course is typically one of rapid deterioration over hours to days if not treated urgently. The widespread nature of the subdural space allows for rapid spread of pus, leading to diffuse cortical dysfunction and potentially life-threatening complications like cerebral edema, herniation, cortical vein thrombosis, venous sinus thrombosis, and sepsis.

Diagnosis of Subdural Empyema

Prompt diagnosis of subdural empyema is critical due to its potential for rapid neurological decline. A high index of suspicion is needed in any patient presenting with fever, headache, altered mental status, meningeal signs, and focal neurological deficits, particularly if they have a history of recent sinusitis, otitis, head trauma, or neurosurgery.

Differential Diagnosis of Subdural Empyema

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Imaging / Lab Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Subdural Empyema | Acute, rapid decline. High fever, severe headache, meningismus, focal deficits, seizures common. History of sinusitis/otitis common. | MRI: Crescentic/layering subdural collection, markedly restricted diffusion (DWI bright, ADC dark), enhancing membranes (dura/leptomeninges). CT: May show collection, enhancing membranes. LP contraindicated typically. |

| Epidural Abscess | More insidious onset typically. Localized headache, fever (~50%). Focal deficits/meningismus uncommon unless complicated. | MRI/CT: Lenticular collection between skull & dura. Enhancing adjacent dura. Pus may restrict diffusion. |

| Bacterial Meningitis | Fever, headache, neck stiffness, altered mental status. No focal collection initially. Focal deficits/seizures less common than SDE early on. | MRI: May show leptomeningeal enhancement. LP (if safe) shows CSF pleocytosis (neutrophils), low glucose, high protein, positive Gram stain/culture. Imaging often normal early. |

| Brain Abscess (Intraparenchymal) | Subacute onset usually. Headache, fever (~50%), focal deficits related to location within brain tissue. Less prominent meningismus than SDE. | MRI/CT: Ring-enhancing lesion *within* brain parenchyma, central restricted diffusion (DWI bright), surrounding edema. |

| Subdural Hematoma (Acute/Chronic) (Type of Intracranial Hemorrhage) | History of trauma (may be minor in chronic). Headache, fluctuating consciousness, focal deficits. Fever/meningismus absent unless infected (rare). | CT/MRI: Crescentic subdural collection. Density/signal varies with age of blood. Enhancing membranes in chronic SDH. No DWI restriction typically (unless hyperacute clot). No fever/high inflammatory markers. |

| Herpes Simplex Encephalitis (HSE) | Acute onset fever, headache, confusion, seizures, focal deficits (often temporal lobe related - aphasia, memory changes, personality changes). | MRI: T2/FLAIR hyperintensity +/- hemorrhage in medial temporal lobes & insula (often bilateral asymmetric). LP shows lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, +/- RBCs; PCR for HSV DNA positive. |

| Cortical Vein / Dural Sinus Thrombosis | Headache, seizures, focal deficits (can mimic SDE), altered mental status. May have prothrombotic risk factors or adjacent infection (as cause or consequence). | MRV/CTV confirms lack of flow/thrombus in veins/sinuses. MRI/CT may show venous infarcts (often hemorrhagic). May co-exist with SDE. |

Neuroimaging, especially contrast-enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) including Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI), is crucial for diagnosing suspected subdural empyema.

Diagnostic steps include:

- Neuroimaging:

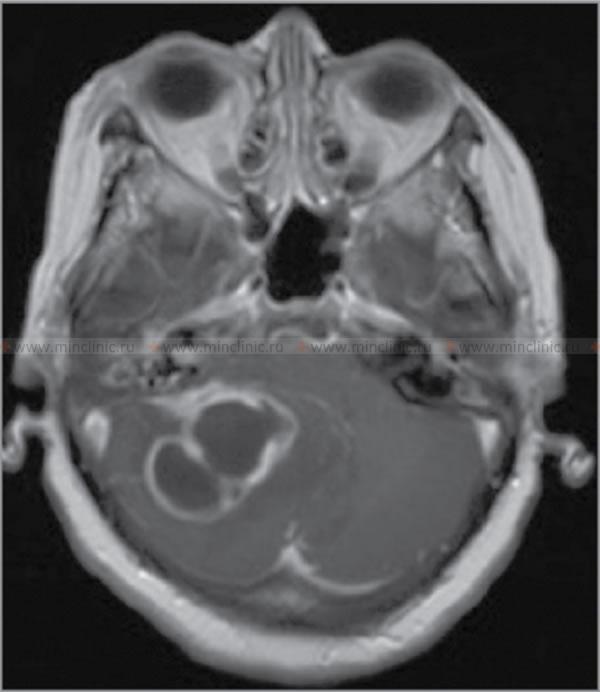

- MRI with Gadolinium Contrast: The investigation of choice due to its high sensitivity and specificity [6]. It typically reveals a collection in the subdural space that follows the contour of the brain surface (crescent-shaped or layering), potentially crossing suture lines but limited by dural reflections (falx, tentorium).

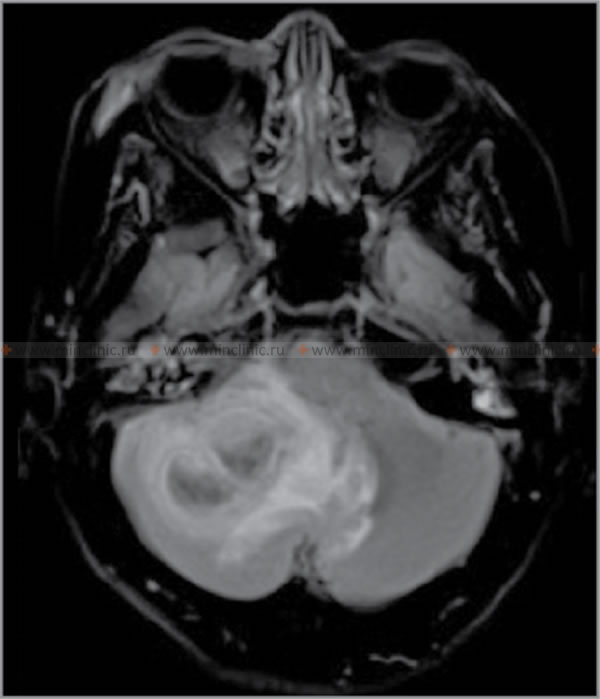

- The collection is often hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2/FLAIR sequences relative to brain tissue.

- Strong enhancement of the adjacent dura and often the underlying leptomeninges (pia-arachnoid) is characteristic after contrast administration, indicating inflammation of these membranes.

- Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) is highly sensitive, showing restricted diffusion (markedly bright signal on DWI, dark on ADC maps) within the empyema due to the high viscosity and cellularity of pus. This is a key feature distinguishing empyema from sterile effusions or chronic hematomas.

- MRI can also effectively show associated complications like cerebral edema, mass effect, cortical vein thrombosis, cerebritis/infarction in the underlying brain parenchyma, and hydrocephalus.

- CT Scan with Contrast: Often the initial imaging in emergency settings. May show a hypodense or sometimes isodense crescent-shaped collection in the subdural space with enhancement of the adjacent meninges after contrast. CT is less sensitive than MRI, especially for small or early collections and for visualizing the restricted diffusion characteristic of pus, but can demonstrate significant mass effect, midline shift, and associated sinus/mastoid disease or fractures.

- MRI with Gadolinium Contrast: The investigation of choice due to its high sensitivity and specificity [6]. It typically reveals a collection in the subdural space that follows the contour of the brain surface (crescent-shaped or layering), potentially crossing suture lines but limited by dural reflections (falx, tentorium).

- Laboratory Tests: Blood tests often show marked leukocytosis with neutrophilia and significantly elevated inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP). Blood cultures should be obtained urgently, as they may be positive, especially if the patient is septic.

- Lumbar Puncture (LP): Generally contraindicated due to the very high risk of brain herniation caused by the significant mass effect often associated with subdural empyema [4, 2]. If performed inadvertently or in highly atypical cases where meningitis is the primary suspicion and imaging definitively rules out significant mass effect (rarely advisable), CSF typically shows findings consistent with parameningeal infection: high protein, high white cell count (predominantly neutrophils), and normal or low glucose. CSF Gram stain and cultures are often negative unless there is concomitant meningitis or rupture into the subarachnoid space.

- Source Evaluation: Imaging of paranasal sinuses (CT) or temporal bones (CT) is important to identify and plan treatment for the likely primary source of infection.

Diagnosing subdural empyema based solely on clinical grounds is exceptionally difficult because its symptoms overlap significantly with severe meningitis, brain abscess, and other intracranial infections, and these conditions can coexist. The combination of rapidly progressing neurological deficits, seizures, high fever, and meningeal signs in a patient with recent sinusitis or otitis should strongly suggest subdural empyema until proven otherwise. Prompt neuroimaging confirmation is essential.

Treatment of Subdural Empyema

Subdural empyema is a **neurosurgical emergency** requiring immediate and aggressive intervention [11].

- Urgent Surgical Drainage: Prompt and adequate drainage of the subdural pus collection is paramount for survival and functional outcome. This is typically achieved via:

- Craniotomy: A large bone flap is created to allow wide exposure of the subdural space, thorough evacuation of pus (which can be widespread and viscous), lysis of any adhesions or loculations, copious irrigation, and exploration for the source (e.g., dural defect). This is often the preferred method for extensive empyemas to ensure complete drainage [2, 4].

- Burr Holes: Multiple burr holes can be placed strategically over the collection for drainage and irrigation, sometimes with placement of subdural catheters for continued drainage or irrigation postoperatively. This may be considered for more localized, fluid collections or in patients too unstable for craniotomy, but carries a higher risk of incomplete drainage and need for re-operation [12].

- Antibiotic Therapy: High-dose, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics that achieve good CNS penetration must be started immediately (ideally after blood cultures drawn but without delaying surgery). Initial empiric therapy should cover likely pathogens from sinus/ear sources (Streptococci - including penicillin-resistant strains, Haemophilus influenzae, anaerobes) and Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA). Common regimens might include vancomycin PLUS a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin (e.g., ceftriaxone, cefepime) PLUS metronidazole. Therapy must be adjusted based on culture results and sensitivities from surgically obtained pus and continued for a prolonged period (typically at least 3-6 weeks intravenously, potentially longer), guided by clinical and imaging response [8].

- Supportive Care: This is crucial and includes intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring for severely ill patients. Management focuses on controlling seizures (antiepileptic drugs are often given prophylactically and continued long-term if seizures occur), aggressive control of fever, management of cerebral edema and potential ICP elevation (though often less severe than with intraparenchymal mass lesions, herniation can still occur), maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion, fluid and electrolyte balance, and nutritional support. Use of corticosteroids (dexamethasone) is controversial and generally not recommended routinely, reserved for cases with severe edema and mass effect causing neurological compromise, and used for the shortest possible duration [1].

Aggressive treatment combining prompt, adequate surgical drainage and prolonged targeted antibiotics is essential for survival. Despite optimal management, subdural empyema carries a significant mortality rate (historically high, now reported between 6-20 percent in recent series [2, 5]) and a high rate of long-term neurological sequelae (such as epilepsy occurring in 30-50%, hemiparesis, cognitive deficits) in survivors, underscoring the need for rapid diagnosis and intervention [12].

![]() Attention! Subdural empyema is a critical neurological emergency. Symptoms like rapidly worsening severe headache, high fever, neck stiffness, confusion, seizures, or focal weakness demand immediate emergency medical evaluation. Early diagnosis and treatment are vital to prevent death or severe long-term disability. Never delay seeking expert medical care if subdural empyema is suspected.

Attention! Subdural empyema is a critical neurological emergency. Symptoms like rapidly worsening severe headache, high fever, neck stiffness, confusion, seizures, or focal weakness demand immediate emergency medical evaluation. Early diagnosis and treatment are vital to prevent death or severe long-term disability. Never delay seeking expert medical care if subdural empyema is suspected.

References

- Osborn AG, Salzman KL, Jhaveri MD, et al. Osborn's Brain. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Nathoo N, Nadvi SS, van Dellen JR, Gouws E. Intracranial subdural empyemas in the era of computed tomography: a review of 699 cases. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(3):529-35; discussion 535-6. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199903000-00040

- Brouwer MC, van de Beek D. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of brain abscesses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017;30(1):129-134. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000334

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 9th ed. Thieme; 2020.

- Osman Farah M, et al. Subdural Empyema: A Single Institution Experience. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:e429-e435. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.12.101

- Wong AM, et al. The role of diffusion-weighted imaging in the diagnosis and management of intracranial infections. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2004;14(2):177-95, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2004.03.004

- Lai PH, Hsu SS, Ding SW, et al. Brain abscess and necrotic brain tumor: discrimination with proton MR spectroscopy and diffusion-weighted imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(8):1369-77.

- Chapter 91: Brain Abscess and Other Parameningeal Infections. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Sexton DJ, et al. Spinal epidural abscess. UpToDate. Accessed [Insert Access Date - e.g., April 20, 2024]. (Subscription required - principles often similar to cranial)

- Germiller JA, Monin DL, Sparano AM, et al. Intracranial complications of sinusitis in children and adolescents and their outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(9):969-76. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.9.969

- Tunkel AR, Hasbun R, Bhimraj A, et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Healthcare-Associated Ventriculitis and Meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(6):e34-e65. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw861

- French H, Schaefer N, Keijzers G, Barison D, Olson S. Subdural empyema: a review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21(12):2037-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.05.007

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)