Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

Sinusitis-Associated Intracranial Complications: Overview

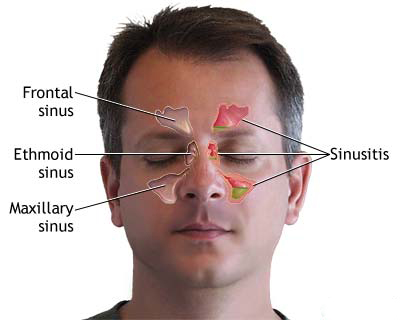

Inflammation of the paranasal sinuses (sinusitis), whether acute or chronic, can rarely but seriously extend beyond the sinus cavities, leading to complications within the orbit (ophthalmic complications) and, more critically, within the cranial cavity (intracranial complications) [1]. These complications arise due to the close anatomical relationship between the sinuses and intracranial structures, facilitated by thin bony partitions, interconnecting valveless venous drainage pathways allowing bidirectional flow, and potential direct extension through bone erosion or congenital/acquired bony dehiscences. Prompt recognition and aggressive treatment are vital as these complications carry significant risks of permanent neurological deficits, vision loss, sepsis, and mortality [2].

While less common than orbital complications, intracranial complications (often termed rhinogenic intracranial complications) occur in an estimated 3-11% of patients hospitalized for sinusitis [3]. They are most frequently associated with frontal sinusitis (due to proximity to the anterior cranial fossa and potential for posterior table erosion or spread via diploic veins) and sphenoid sinusitis (due to proximity to the cavernous sinus, pituitary gland, optic nerves, internal carotid arteries, and middle cranial fossa). Ethmoid sinusitis can also lead to intracranial spread, often via thrombophlebitis of draining veins or direct extension into the anterior cranial fossa. Maxillary sinusitis is the least common source of isolated intracranial issues but can contribute via spread to other sinuses or orbital veins. Facial trauma involving sinus fractures, sinus surgery, and immunocompromised states can also predispose to these complications.

The major types of intracranial complications arising from sinusitis include:

- Meningitis (Bacterial Meningitis): Inflammation of the leptomeninges (pia and arachnoid mater) due to bacterial invasion of the subarachnoid space. This can occur via direct extension through eroded bone/dura, retrograde thrombophlebitis, or hematogenous seeding. Presents classically with fever, severe headache, neck stiffness (nuchal rigidity), and altered mental status.

- Epidural Abscess: Collection of pus accumulating between the inner surface of the skull and the outer layer of the dura mater. Often forms adjacent to the infected sinus (e.g., frontal epidural abscess). Symptoms can be subtle initially (localized headache, fever) but it represents intracranial extension and can progress. Pott's puffy tumor specifically refers to frontal osteomyelitis with an associated subgaleal (under the scalp) and often epidural abscess.

- Subdural Empyema (Subdural Abscess): Collection of pus in the potential space between the dura mater and the arachnoid mater. This is a neurosurgical emergency as the infection can spread rapidly over the cerebral hemispheres due to the lack of anatomical barriers in this space. Often arises from frontal sinusitis via thrombophlebitis of bridging veins draining into the superior sagittal sinus. Presents acutely with high fever, severe headache, meningismus, rapidly deteriorating mental status, seizures, and prominent focal neurological deficits (e.g., hemiparesis).

- Brain Abscess (Intracerebral Abscess): Localized collection of pus within the brain parenchyma itself. Typically occurs in the frontal lobe secondary to frontal or ethmoid sinusitis (via direct extension or thrombophlebitis) but can also occur elsewhere. Presentation is often subacute with headache, fever (in ~50%), focal neurological deficits corresponding to the location (e.g., personality changes, motor weakness, aphasia for frontal lobe), seizures, and eventual signs of increased intracranial pressure.

- Dural Venous Sinus Thrombosis (Septic Thrombophlebitis): Inflammation and septic clotting within the major venous drainage channels of the brain encased within the dura. Most commonly involves the superior sagittal sinus (associated with frontal/ethmoid sinusitis) or the cavernous sinus (associated with sphenoid/ethmoid/maxillary sinusitis or mid-facial infections). Presents with severe headache, fever/sepsis, seizures, focal neurological deficits (often bilateral with SSS thrombosis), signs of increased ICP (papilledema), and specific signs related to the affected sinus (e.g., orbital signs [proptosis, chemosis] and multiple cranial nerve palsies [III, IV, VI, V1/V2] in cavernous sinus thrombosis). Carries high risk of venous infarction, hemorrhage, and poor outcome if not treated aggressively.

- Osteomyelitis of the Skull Bones: Infection and inflammation of the cranial bones themselves, often contiguous with the infected sinus (e.g., frontal bone in Pott's puffy tumor). Requires prolonged antibiotics and often surgical debridement.

- Rhinogenic Arachnoiditis (Arachnoiditis): Chronic inflammation and scarring (adhesions) of the arachnoid mater, potentially causing hydrocephalus, cranial nerve dysfunction, or chronic headache. Often develops as a late sequela of previous intracranial infection (meningitis, abscess) or inflammation related to sinusitis. Typically presents more chronically than the acute infectious complications.

The specific symptoms often depend on the type and location of the complication, as well as the speed of onset. Epidural abscesses may be relatively silent initially. Subdural empyemas and meningitis typically present acutely and dramatically. Brain abscess symptoms may evolve more subacutely initially. Venous sinus thrombosis often causes severe headache and signs related to venous congestion and increased ICP.

Frontal lobe abscesses, arising from frontal or ethmoid sinusitis, can initially manifest with subtle symptoms like personality changes (apathy, irritability, disinhibition), impaired judgment, lack of insight, or executive dysfunction ("frontal lobe syndrome") before causing more obvious signs like motor deficits (contralateral hemiparesis), motor (Broca's) aphasia (if dominant hemisphere), anosmia (loss of smell due to olfactory bulb/tract involvement), or seizures.

The venous drainage patterns are critical for understanding pathways of spread. Veins from the upper nasal cavity and ethmoid/frontal sinuses drain superiorly via diploic veins and bridging veins into the superior sagittal sinus. Veins from the mid-face, sphenoid, and ethmoid sinuses have connections to the cavernous sinus via the orbital veins (superior/inferior ophthalmic veins) and pterygoid plexus, creating the risk pathway for cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Neuroimaging, especially contrast-enhanced Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with venography (MRV), is crucial for accurately diagnosing suspected sinusitis-associated intracranial complications and differentiating between meningitis, different types of abscesses/empyemas, and venous thrombosis.

Historically, intracranial complications of sinusitis, particularly subdural empyema and septic venous sinus thrombosis, had extremely high mortality rates (>50%). Modern management with prompt diagnosis via advanced imaging (CT/MRI), potent broad-spectrum antibiotics, and timely, often combined neurosurgical and otolaryngologic surgical intervention has dramatically improved outcomes, although these remain serious, potentially life-threatening conditions requiring urgent management [4].

Prevention hinges on effective and timely treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis and appropriate management of chronic sinusitis, especially in high-risk individuals. Recognizing the potential for intracranial spread ("red flag" symptoms like severe headache, altered mental status, focal neurological signs, persistent fever despite antibiotics) is key when evaluating patients with sinusitis.

Diagnosis of Sinusitis-Associated Intracranial Complications

Diagnosing intracranial complications arising from sinusitis requires a high index of suspicion when a patient with known or suspected sinusitis presents with concerning neurological symptoms, severe systemic illness, or fails to improve with standard sinusitis treatment. Prompt and accurate diagnosis is crucial for initiating life-saving therapy.

Differential Diagnosis of Neurological Symptoms in a Patient with Sinusitis

| Complication / Condition | Key Clinical Features | Primary Diagnostic Tool / Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Meningitis | Severe headache, high fever, neck stiffness (meningismus), photophobia, altered mental status (confusion, lethargy). Rapid onset typically. | Lumbar Puncture (LP) (after imaging if needed to rule out mass effect): CSF shows bacterial pattern (high WBC-neutrophils, high protein, low glucose). MRI Brain: May show leptomeningeal enhancement. CT Sinus: Identifies sinusitis source. |

| Epidural Abscess | Often subtle initially. Persistent localized headache near affected sinus, fever (variable), localized tenderness/swelling (e.g., Pott's puffy tumor over forehead). Usually NO focal deficits or significant meningismus unless large or complicated. | Contrast-Enhanced MRI Brain (preferred) or CT Brain: Shows lenticular collection between inner skull table & dura, with enhancement of the adjacent dura. CT Sinus: Shows source sinusitis +/- bone erosion. |

| Subdural Empyema | Neurosurgical emergency! Acute, rapid decline. High fever, severe headache, meningismus, prominent focal neurological deficits (hemiparesis), seizures common. Rapidly deteriorating mental status. | Contrast-Enhanced MRI Brain with DWI: Shows crescentic/layering subdural collection, often widespread. Pus shows restricted diffusion (DWI bright, ADC dark). Enhancement of bounding membranes (dura/arachnoid). LP strongly contraindicated usually. CT less sensitive. |

| Brain Abscess (Intracerebral) | Subacute onset typically (days/weeks). Headache (often progressive), fever (~50%), focal neurological deficits (depend on location, e.g., frontal lobe syndrome, hemiparesis), seizures. Signs of increased ICP develop later. | Contrast-Enhanced MRI Brain with DWI: Shows ring-enhancing lesion within brain parenchyma. Central cavity shows restricted diffusion (DWI bright, ADC dark) characteristic of pus. Surrounding vasogenic edema. LP contraindicated if significant mass effect. |

| Dural Venous Sinus Thrombosis (Septic) | Severe headache (often prominent feature), seizures, focal deficits (can be bilateral/multifocal due to venous infarcts), signs of increased ICP (papilledema). Fever/sepsis common. Specific signs depend on sinus (e.g., Cavernous sinus: orbital signs, CN palsies). | MR Venography (MRV) or CT Venography (CTV) is diagnostic: Confirms lack of flow / filling defect (thrombus) within the dural sinus(es). Contrast MRI Brain may show associated venous infarcts (often hemorrhagic) or intense dural enhancement near sinus. |

| Orbital Complications (Cellulitis, Abscess) | Primary orbital signs: Proptosis, eyelid edema/erythema, restricted/painful eye movements, chemosis, +/- decreased vision. Neurological signs typically absent unless extending intracranially. | Contrast-Enhanced CT Orbits & Sinuses (often initial test) or MRI Orbits: Shows orbital inflammation (fat stranding) or abscess collection (subperiosteal or intraorbital), along with causative sinus disease. Brain parenchyma typically normal. |

| Migraine or Tension-Type Headache with coincidental Sinusitis | Headache may have typical primary headache features (migraine: pulsating, nausea, photo/phonophobia; TTH: bilateral, pressing). Sinusitis symptoms may be present but headache pattern may not fit typical "sinus headache". No fever/meningismus/focal deficits typically. | Clinical diagnosis based on headache pattern meeting ICHD criteria. Imaging (if done) shows sinus findings but brain is normal, and sinus findings may not correlate temporally or spatially with headache pattern. Normal neurological exam. |

Note: Multiple complications can co-exist (e.g., subdural empyema with underlying brain abscess or meningitis).

Key steps in the diagnostic process include:

- Clinical Assessment: A thorough history focusing on sinus symptoms, headache characteristics (severity, location, quality, timing), fever, visual changes, neurological symptoms (weakness, numbness, confusion, seizures), and neck stiffness. Physical examination must include vital signs, detailed neurological assessment (mental status, cranial nerves including funduscopy, motor, sensory, reflexes, meningeal signs), ophthalmological assessment (visual acuity, fields, motility, proptosis), and rhinological assessment (nasal endoscopy if possible). The presence of "red flag" symptoms mandates urgent investigation.

- Laboratory Tests: Complete blood count (CBC) often shows leukocytosis with neutrophilia. Inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) are usually elevated but non-specific. Blood cultures should be obtained urgently, especially if fever or signs of sepsis are present, as they may identify the causative organism.

- Neuroimaging: This is essential for diagnosis and determining the type and extent of complication.

- Contrast-Enhanced Brain MRI with MR Venography (MRV): Generally considered the imaging modality of choice when intracranial complications are suspected, particularly for suspected subdural empyema, brain abscess, or venous sinus thrombosis, due to its superior soft tissue contrast and ability to visualize inflammation, pus (DWI), and venous flow [5, 2]. Should include orbital views if concurrent orbital complications are possible.

- Contrast-Enhanced Brain CT with CT Venography (CTV): Often performed first in the emergency setting due to speed and availability, especially to rule out hemorrhage or hydrocephalus rapidly. Excellent for showing bone detail (sinus erosion, osteomyelitis, fractures) and identifying epidural abscesses. Contrast helps visualize abscess rims and dural enhancement. CTV is an alternative to MRV for diagnosing venous sinus thrombosis [1].

- CT Sinuses: Often performed concurrently or as part of the head CT protocol to delineate the extent of underlying sinus disease and identify the likely source.

- Lumbar Puncture (LP) for CSF Analysis: Indicated if meningitis is suspected clinically AND neuroimaging (usually CT first) has excluded significant mass effect (midline shift, herniation) or obstructive hydrocephalus that would make LP unsafe. CSF analysis confirms meningitis (bacterial pattern: high WBC [neutrophils], high protein, low glucose) and allows for Gram stain/culture to identify the pathogen. LP is generally contraindicated if epidural abscess, subdural empyema, or brain abscess with significant mass effect is suspected or confirmed on imaging, due to the high risk of cerebral herniation.

- Otolaryngology (ENT) and Ophthalmology Consultation: Essential for comprehensive assessment of the sinus source and any orbital involvement, respectively.

Diagnosing these complications often requires interpreting the clinical picture in conjunction with characteristic imaging findings. For example, restricted diffusion (bright on DWI, dark on ADC maps) within a collection is highly specific for pus (subdural empyema, brain abscess) or acute infarction. Lack of flow within a dural sinus on MRV/CTV confirms thrombosis. Enhancement patterns (leptomeningeal vs. pachymeningeal vs. ring enhancement) help differentiate between complications.

Treatment of Sinusitis-Associated Intracranial Complications

The management of sinusitis-associated intracranial complications is a medical and surgical emergency requiring immediate hospitalization, typically in an intensive care setting initially, and a coordinated multidisciplinary approach involving Otolaryngology (ENT), Neurosurgery, Infectious Disease specialists, Neurology, and Ophthalmology [1, 3]. Treatment principles focus on rapid administration of appropriate antibiotics, urgent surgical drainage of purulent collections, and definitive management of the underlying sinus infection source.

- Medical Management:

- Antibiotics: Immediate initiation of high-dose, broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics with excellent central nervous system (CNS) penetration is mandatory upon suspicion. Empiric regimens must cover common sinus pathogens (aerobes and anaerobes, including S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus, Streptococci, anaerobes like Bacteroides, Prevotella, Fusobacterium).

- A standard empiric regimen often includes: Vancomycin (for MRSA and resistant pneumococci) PLUS a third-generation cephalosporin (e.g., Ceftriaxone or Cefotaxime) PLUS Metronidazole (for anaerobic coverage) [6].

- Alternatives like meropenem might be used depending on local resistance or allergies.

- Antibiotics are subsequently tailored based on culture results (from sinus, abscess, blood, or CSF) and sensitivities.

- Duration of IV therapy is prolonged, typically at least 3-6 weeks, and often longer (e.g., 6-8 weeks or more for brain abscess or osteomyelitis), guided by the specific complication, clinical response, inflammatory markers, and resolution on follow-up imaging.

- Supportive Care: Management of fever (antipyretics), pain (analgesics), hydration, nutrition, and prevention of complications (e.g., DVT prophylaxis, stress ulcer prophylaxis).

- Management of Increased ICP: If present, requires urgent intervention. Measures include head elevation (30 degrees), osmotic therapy (Mannitol or hypertonic saline), ensuring adequate oxygenation and ventilation (avoiding hypercapnia), and potentially sedation. Neurosurgical consultation for possible ICP monitoring or CSF diversion (EVD) is essential.

- Seizure Management: Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs, e.g., levetiracetam, fosphenytoin) are administered promptly if seizures occur. Prophylactic AED use is often recommended, especially for subdural empyema and brain abscess, due to the high risk of seizures, although duration of prophylaxis is debated [7].

- Corticosteroids (Dexamethasone): Role is limited and complication-specific. May be used adjunctively in bacterial meningitis (given with or just before first antibiotic dose, especially if pneumococcal cause suspected). May be considered short-term for significant vasogenic edema causing mass effect from brain abscesses, but use is controversial as it can reduce antibiotic penetration and mask symptoms; generally avoided or used very cautiously. Contraindicated if fungal infection is suspected. Not typically used for subdural empyema or epidural abscess unless severe life-threatening edema is present.

- Anticoagulation: Heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, followed by oral anticoagulation (e.g., warfarin), is often recommended for septic dural venous sinus thrombosis once initial stabilization occurs and significant intracranial hemorrhage has been excluded, to prevent further clot propagation and promote recanalization. Decision requires careful risk-benefit assessment [8].

- Antibiotics: Immediate initiation of high-dose, broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics with excellent central nervous system (CNS) penetration is mandatory upon suspicion. Empiric regimens must cover common sinus pathogens (aerobes and anaerobes, including S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus, Streptococci, anaerobes like Bacteroides, Prevotella, Fusobacterium).

- Surgical Intervention: Prompt surgical intervention is crucial for most intracranial complications (except uncomplicated meningitis). Goals are drainage of purulent collections, reduction of mass effect, obtaining material for culture, and definitive treatment of the underlying sinus infection source.

- Source Control (Sinus Surgery): Eradication of the primary sinus infection is essential for cure and preventing recurrence. This almost always involves Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (ESS) performed by an otolaryngologist to widely open and drain the infected sinuses (involved ethmoids, maxillary, sphenoid, frontal sinuses), remove polyps/diseased tissue, and restore ventilation. This should generally be performed urgently or semi-urgently, often concurrently with or shortly after neurosurgical drainage of intracranial collections. External sinus approaches (e.g., osteoplastic flap for frontal sinus) are less common now but may be needed in specific situations.

- Drainage of Intracranial Collections (Neurosurgery):

- Epidural Abscess: Often drained via the sinus surgery approach (e.g., during ESS or external frontal sinus procedure) by removing the adjacent infected bone. Larger collections, those inaccessible via sinus routes, or those causing significant mass effect may require a separate neurosurgical craniotomy or burr holes for drainage.

- Subdural Empyema: Requires urgent neurosurgical drainage, typically via craniotomy to allow wide exposure, thorough evacuation of pus from the subdural space (which can spread extensively), irrigation, and lysis of adhesions. Multiple burr holes are a less effective alternative associated with higher rates of residual collection and reoperation.

- Brain Abscess: Treatment involves either stereotactic aspiration (image-guided needle drainage, often preferred initially for diagnosis and decompression, especially for deep or multiple abscesses) or craniotomy with excision (surgical removal of the abscess and capsule, considered for larger, superficial, well-encapsulated, multiloculated, or foreign body-associated abscesses, or those failing aspiration).

Conservative management (antibiotics alone without surgery) is rarely sufficient for established intracranial abscesses (epidural, subdural, intracerebral) or subdural empyemas due to the encapsulated nature of the infection and associated mass effect. Early, uncomplicated meningitis or possibly very small epidural collections might respond to medical therapy alone, but require extremely close monitoring and a low threshold for surgical intervention if improvement is not rapid.

Long-term follow-up involving clinical assessment, neurological/ophthalmological evaluation, and repeat neuroimaging (MRI) is essential to monitor for complete resolution, detect any recurrence, manage long-term sequelae (seizures, cognitive deficits, hydrocephalus), and ensure sinus health.

![]() Attention! Intracranial complications of sinusitis are life-threatening emergencies. Symptoms such as severe headache, high fever, altered mental status, seizures, focal neurological deficits, or significant eye swelling/vision changes in the context of sinusitis require immediate emergency medical evaluation. Prompt diagnosis and aggressive combined medical and surgical treatment are critical for survival and minimizing permanent disability.

Attention! Intracranial complications of sinusitis are life-threatening emergencies. Symptoms such as severe headache, high fever, altered mental status, seizures, focal neurological deficits, or significant eye swelling/vision changes in the context of sinusitis require immediate emergency medical evaluation. Prompt diagnosis and aggressive combined medical and surgical treatment are critical for survival and minimizing permanent disability.

References

- Clayman GL, Adams GL, Paugh DR, Koopmann CF Jr. Intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis: a combined institutional review. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(3):234-9. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199103000-00005

- Jones NS, Walker JL, Bassi S, Jones T, Punt J. The intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis: can they be prevented? Laryngoscope. 2002;112(1):59-63. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200201000-00011

- Bayonne E, Kania R, Tran P, Huy B, Herman P. Intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis. A review, typical imaging data and algorithm of management. Rhinology. 2009;47(1):59-65. doi: 10.4193/Rhin08.123

- Singh DC, et al. Intracranial Complications of Rhinosinusitis: Experience at a Tertiary Care Center in North India. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;73(1):84-90. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-02123-1

- Yousem DM, Grossman RI. Neuroradiology: The Requisites. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016.

- Chapter 91: Brain Abscess and Other Parameningeal Infections. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Ratsep T, et al. Seizures and antiseizure prophylaxis after penetrating brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(1):123-7. doi: 10.3171/2008.3.17491

- Canhão P, et al; ISCVT Investigators. Causes and predictors of death in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2005;36(8):1720-5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000173152.84438.1c

- Osborn AG, Salzman KL, Jhaveri MD, et al. Osborn's Brain. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Wald ER, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e262-80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1071

- Pushker N, et al. Role of Corticosteroids in the Management of Orbital Cellulitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(11):629-633. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.123133

- Garcia GH, et al. Criteria for surgical intervention in pediatric orbital cellulitis. J AAPOS. 2009;13(4):399-403. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.02.013

- Chow AW, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):e72-e112. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis370

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)