Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses inflammation diseases ophthalmic complications

Ophthalmic Complications of Nasal and Sinus Inflammation

Inflammatory diseases affecting the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, primarily acute and chronic sinusitis, pose a significant risk for developing serious ophthalmic (eye-related) and potentially subsequent intracranial complications [1]. These complications arise due to the close anatomical proximity and interconnected vascular and lymphatic drainage systems between the sinuses and the orbit (the bony cavity containing the eye and its associated structures). Such complications can lead to severe outcomes, including permanent vision loss, cranial nerve palsies causing double vision, meningitis, epidural or subdural abscess, brain abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and, although rare with modern treatment, mortality [2].

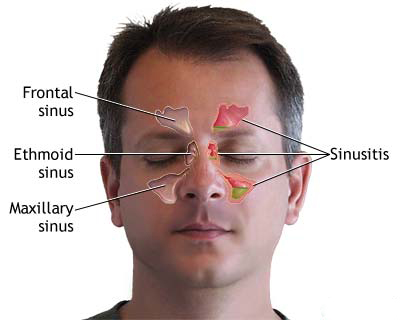

The orbit is largely encased by the paranasal sinuses: the ethmoid sinuses medially, the maxillary sinus inferiorly, the frontal sinus superiorly, and the sphenoid sinus postero-medially. The bony walls separating these structures are often remarkably thin. The lamina papyracea, forming the medial orbital wall adjacent to the ethmoid air cells, is particularly thin (paper-thin) and may possess natural dehiscences (gaps) or be susceptible to erosion by infection or inflammation. Similarly, the orbital floor (roof of the maxillary sinus) can be thin and easily breached.

Posteriorly, the sphenoid sinus and posterior ethmoid cells lie in close proximity to the optic canal (transmitting the optic nerve - CN II, and ophthalmic artery) and the orbital apex/superior orbital fissure region. Inflammation or masses (like mucoceles) in these sinuses can directly compress or inflame the optic nerve, leading to optic neuropathy and vision loss. The superior orbital fissure transmits crucial structures including the oculomotor nerve (CN III), trochlear nerve (CN IV), abducens nerve (CN VI), and branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V1 - ophthalmic division). Inflammation or compression in this region can cause ophthalmoplegia (impaired eye movement), diplopia (double vision), ptosis (CN III), and facial numbness (CN V1). Congenital bony defects (dehiscences) in these walls further facilitate the spread of infection or inflammation [3].

Beyond direct extension through thin or dehiscent bone, infection spreads readily via the valveless venous system connecting the sinuses, face, and orbit. Veins draining the sinuses (e.g., ethmoidal veins, frontal diploic veins) communicate freely with orbital veins (superior and inferior ophthalmic veins), which in turn drain posteriorly into the cavernous sinus. This valveless network allows thrombophlebitis (inflammation and clotting of veins) originating in the sinuses to easily propagate retrogradely into the orbit (causing orbital congestion and inflammation) and potentially intracranially, leading to cavernous sinus thrombosis—a life-threatening emergency. Lymphatic drainage pathways also interconnect these regions. Nerves and arteries, like the anterior and posterior ethmoidal neurovascular bundles passing through foramina in the medial orbital wall, provide additional potential routes for inflammatory spread.

Ophthalmic complications of sinusitis are commonly classified according to the Chandler classification, based on the anatomical extent of involvement [4]:

- Group 1: Inflammatory Edema (Preseptal Cellulitis / Periorbital Cellulitis): Inflammation and edema confined to the tissues anterior to the orbital septum (eyelids and periorbital skin). The orbital septum is a fibrous membrane acting as a barrier. Characterized by eyelid swelling and redness, but crucially, visual acuity, pupillary reactions, and eye movements are typically normal, and there is no proptosis.

- Group 2: Orbital Cellulitis: Infection spreads posterior to the orbital septum, involving the orbital contents (fat and muscles). Presents with eyelid edema and erythema PLUS orbital signs: proptosis (bulging eye), chemosis (conjunctival swelling), pain, and often restricted and/or painful eye movements (ophthalmoplegia). Vision may be affected due to optic nerve inflammation or congestion.

- Group 3: Subperiosteal Abscess: Collection of pus forms between an orbital bone wall and its overlying periosteum (lining). Most commonly occurs along the medial wall (lamina papyracea) adjacent to infected ethmoid sinuses. Causes significant proptosis, displacement of the globe (often downward and outward), restricted eye movements, pain, and potential vision compromise due to pressure.

- Group 4: Orbital Abscess: Discrete collection of pus forms *within* the orbital fat/tissues themselves, posterior to the septum and not confined by the periosteum. Presents similarly to severe orbital cellulitis but often with more marked proptosis, severe ophthalmoplegia, and a higher risk of rapid vision loss due to direct optic nerve compression or ischemia.

- Group 5: Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis: Spread of infection/thrombophlebitis posteriorly to the cavernous sinus. Presents with potentially bilateral orbital signs (though often starting unilaterally and progressing), severe headache, high fever/sepsis, marked proptosis, chemosis, complete or near-complete ophthalmoplegia (multiple cranial nerve palsies III, IV, VI), sensory loss in the V1/V2 distribution, decreased vision, and potentially altered mental status or signs of meningitis/intracranial infection. This is a critical neurological and ophthalmological emergency.

Non-infectious complications include mechanical effects from expanding benign sinus lesions:

- Mucocele/Pyocele: Obstruction of a sinus ostium leads to gradual accumulation of sterile mucus (mucocele) or infected pus (pyocele) within the sinus cavity. Gradual expansion erodes bone and displaces orbital contents, causing proptosis, diplopia, or pain. Most common in frontal and ethmoid sinuses.

- Bone Tumors: Benign (e.g., osteoma, fibrous dysplasia) or malignant tumors originating in the sinuses or nasal cavity can invade the orbit, causing similar mass effect symptoms.

Visual impairment can also arise from optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve) secondary to adjacent sinus disease (especially sphenoid or posterior ethmoid sinusitis). This can occur via direct spread of inflammation through the optic canal, compression from mucoceles/pyoceles or inflammation, or possibly ischemic or immune-mediated mechanisms, sometimes even without obvious signs of orbital cellulitis [5].

Complications are most commonly associated with ethmoid sinusitis (especially causing medial subperiosteal abscess) and frontal sinusitis due to their extensive contact with the orbit and thin separating walls. Acute exacerbations of chronic sinusitis are frequent triggers for orbital involvement.

Acute frontal sinusitis may lead to superior or superomedial subperiosteal abscess formation beneath the orbital roof. This typically causes significant upper eyelid swelling and erythema, downward and outward displacement (proptosis) of the eyeball, and limitation of upward gaze.

Chronic frontal sinusitis can sometimes cause chronic periostitis (inflammation of the bone lining) of the orbital rim or sinus walls, presenting as localized tenderness and persistent soft tissue swelling. Pott's puffy tumor refers specifically to swelling over the frontal bone due to underlying frontal sinusitis with associated subperiosteal abscess formation on the outer table of the skull.

Maxillary sinusitis less frequently causes orbital complications compared to ethmoid or frontal disease. However, severe infections can erode the thin orbital floor (maxillary sinus roof), potentially leading to inferior subperiosteal abscess, orbital cellulitis, or rarely, orbital phlegmon (diffuse, severe inflammation without a discrete abscess). Dental infections can also spread upwards into the maxillary sinus and then the orbit.

Ethmoid sinusitis is a very common source of orbital complications, especially in children, due to the thinness of the lamina papyracea and the fact that ethmoid sinuses are developed earlier than frontal sinuses. Medial subperiosteal abscess is the classic complication arising from ethmoiditis.

Inflammation involving the posterior sinuses (sphenoid and posterior ethmoid) carries a particularly high risk of severe complications due to direct proximity to the optic nerve, cavernous sinus, pituitary gland, and intracranial structures. Orbital cellulitis originating posteriorly is common. Cavernous sinus thrombosis and meningitis are relatively more frequent sequelae compared to complications arising solely from anterior sinusitis. Functional visual disturbances are also more common and concerning:

- Decrease in visual acuity (due to optic nerve compression, inflammation, or ischemia).

- Constriction or defects in the visual field (e.g., central scotoma, altitudinal defect).

- Enlargement of the physiological blind spot (scotoma) or development of central/paracentral scotomas on formal testing.

- Afferent pupillary defect (Marcus Gunn pupil) indicating optic neuropathy.

Diagnosis of Ophthalmic Complications from Sinusitis

Prompt diagnosis is critical to prevent permanent vision loss and potentially life-threatening intracranial spread. Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical assessment (history and physical examination, including detailed ophthalmological and rhinological evaluation) and targeted imaging studies.

Differential Diagnosis of Orbital Inflammation/Swelling

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Imaging / Lab Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Orbital Complication of Sinusitis (Cellulitis, Subperiosteal/Orbital Abscess) | History/signs of sinusitis (often acute). Proptosis, pain with eye movement (ophthalmoplegia), +/- decreased vision, chemosis, eyelid edema/erythema. Fever common. Usually unilateral. | CT/MRI shows sinus opacification +/- bone erosion. Orbital findings depend on stage: fat stranding (cellulitis), collection displacing periosteum (SPA), intra-orbital rim-enhancing collection (OA). Elevated WBC, ESR/CRP. |

| Preseptal Cellulitis | Infection/inflammation strictly *anterior* to orbital septum. Eyelid edema, erythema, warmth, tenderness. Crucially: NO proptosis, NO pain with eye movement, normal vision, normal pupils. Often from local skin break/infection (insect bite, hordeolum) or spread from sinusitis. | Clinical diagnosis primarily. Imaging (CT/MRI) if needed shows eyelid/periorbital soft tissue swelling anterior to septum, *normal* orbital contents posteriorly. |

| Idiopathic Orbital Inflammatory Syndrome (IOIS / Orbital Pseudotumor) | Acute/subacute painful onset, proptosis, restricted eye movements, eyelid swelling/erythema. Can mimic infection but often afebrile or low-grade fever. May involve lacrimal gland, extraocular muscles (incl. tendons), orbital fat diffusely, sclera (scleritis). Can be bilateral (~30%). | MRI/CT shows enlargement and enhancement of involved orbital structures (muscles *including tendons*, lacrimal gland, diffuse fat stranding, scleral thickening). Sinuses typically clear. Often responds rapidly and dramatically to high-dose corticosteroids. Biopsy may be needed for atypical/refractory cases. |

| Thyroid Eye Disease (TED / Graves' Ophthalmopathy) | Often associated with history of hyperthyroidism (can occur when euthyroid/hypothyroid). Usually bilateral (can be asymmetric). Proptosis (often axial), eyelid retraction (stare), lid lag, restricted eye movements (esp. upgaze/abduction due to inferior/medial rectus involvement). Minimal pain typically, more discomfort/grittiness. Chemosis common. | CT/MRI shows characteristic extraocular muscle belly enlargement, sparing the tendons. Increased orbital fat volume common. Thyroid function tests often abnormal. TRAb antibodies often positive. |

| Orbital Tumor (e.g., Lymphoma, Metastasis, Rhabdomyosarcoma [child], Lacrimal Gland Tumor, Optic Nerve Glioma) | Often slower onset (except some aggressive tumors like rhabdo). Progressive, often painless proptosis, palpable mass possible, vision changes (compression/infiltration), diplopia. Systemic symptoms depend on type (lymphoma, mets). | CT/MRI shows discrete mass lesion, characteristics depend on tumor type (lymphoma often molds to structures, mets can be anywhere, glioma enlarges optic nerve). Variable enhancement, potential bone destruction. Biopsy required for diagnosis. Systemic workup needed for metastasis/lymphoma. |

| Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis (Septic) | Acute, severe illness. Headache, high fever, potentially bilateral orbital signs (proptosis, chemosis, ophthalmoplegia), multiple CN palsies (III, IV, VI, V1/V2), decreased vision. Often septic appearance, altered mental status. | MRV/CTV confirms thrombus/lack of flow in cavernous sinus(es). MRI may show sinus enlargement, filling defects, abnormal enhancement. Often secondary to central facial, sinus, or dental infection. Blood cultures often positive. |

| Carotid-Cavernous Fistula (CCF) | Abnormal connection between carotid artery and cavernous sinus. Often post-traumatic (high flow) or spontaneous (dural, low flow). Pulsatile proptosis, orbital bruit (audible whoosh), marked chemosis & injection ('red eye'), dilated corkscrew conjunctival vessels, ophthalmoplegia, increased intraocular pressure, +/- vision loss. | MRI/MRA/CTA shows dilated superior ophthalmic vein, enlarged cavernous sinus with flow-related signal. DSA (conventional angiography) is gold standard for diagnosis, classification, and treatment planning (embolization). |

| Dacryoadenitis / Dacryocystitis | Dacryoadenitis: Inflammation/infection of lacrimal gland (superotemporal orbit). Pain, swelling, redness, tenderness in outer upper eyelid region, S-shaped ptosis. Dacryocystitis: Infection of lacrimal sac (medial canthus, inferior to medial canthal tendon). Pain, redness, swelling over lacrimal sac, tearing, +/- pus discharge from punctum upon pressure. | Clinical diagnosis often sufficient. CT/MRI confirms lacrimal gland enlargement/enhancement (dacryoadenitis) or lacrimal sac distension/inflammation/abscess (dacryocystitis). Distinct locations from typical sinusitis complications. |

| Orbital Trauma with Hematoma/Fracture (related to TBI) | History of direct trauma. Periorbital bruising (ecchymosis), swelling, pain, restricted movement (muscle entrapment in blowout fracture), diplopia, +/- proptosis (hematoma), enophthalmos (blowout fx). | CT orbit is investigation of choice, shows fractures (esp. floor/medial wall), muscle entrapment, retrobulbar hematoma. No signs of infection typically (unless fracture is open/compound). |

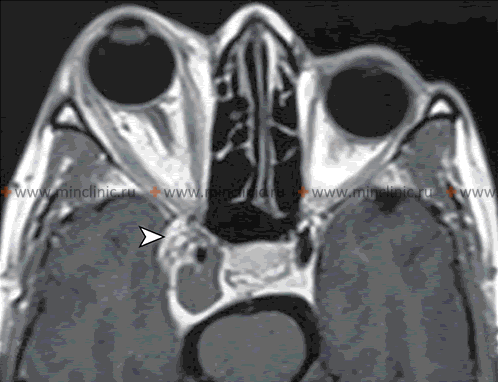

Neuroimaging techniques like Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) play a crucial role in evaluating suspected orbital and potential intracranial complications arising from inflammation of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses.

Clinical Evaluation:

- History: Elicit detailed history of recent or chronic sinusitis symptoms (facial pain/pressure, purulent nasal congestion/discharge, anosmia, fever, headache), prior sinus surgery or trauma. Document onset, duration, and progression of orbital symptoms (pain, swelling, redness, vision changes - blurriness, double vision, field loss, pain with movement), and associated systemic symptoms (fever, malaise).

- Ophthalmological Examination: Crucial for staging and monitoring. Includes:

- Visual acuity testing (corrected).

- Pupillary examination (size, reactivity, check for relative afferent pupillary defect - RAPD or Marcus Gunn pupil, indicating optic neuropathy).

- Visual field assessment (confrontation testing at bedside, formal perimetry if possible).

- Assessment of extraocular movements (checking for limitation, pain with movement - ophthalmoplegia).

- Evaluation for proptosis (forward bulging of the eye, measured with exophthalmometer relative to lateral orbital rim).

- External examination of eyelids (edema, erythema, warmth) and conjunctiva (injection, chemosis - swelling).

- Intraocular pressure measurement (may be elevated due to orbital congestion).

- Slit lamp examination (anterior segment).

- Dilated funduscopic examination (to assess optic disc for swelling/papilledema or pallor/atrophy, check for retinal venous engorgement, choroidal folds, or signs of retinal vein occlusion).

- Rhinological Examination: Nasal endoscopy by an otolaryngologist to assess nasal cavity, turbinates, septum, identify purulence draining from sinus ostia, polyps, or anatomical factors contributing to sinusitis. Cultures of purulent drainage may be obtained.

- General Examination: Assess for fever, signs of sepsis (tachycardia, hypotension), altered mental status, neck stiffness (meningismus), or focal neurological deficits suggesting intracranial involvement (requiring urgent brain imaging).

Imaging Studies:

- Contrast-Enhanced CT Scan of the Orbits and Paranasal Sinuses: This is typically the initial imaging modality of choice in the acute setting, especially if orbital abscess is suspected [8]. Advantages include rapid acquisition, wide availability, and excellent visualization of:

- Bony anatomy: Sinus opacification, air-fluid levels, bone erosion or dehiscence (e.g., lamina papyracea).

- Orbital complications: Preseptal vs. orbital involvement, orbital fat stranding (cellulitis), subperiosteal fluid collections, discrete rim-enhancing intraorbital fluid collections (abscess).

- Extent of sinus disease.

- MRI of the Orbits and Brain with Gadolinium Contrast: MRI provides superior soft tissue contrast and is often complementary or preferred if CT is equivocal, if intracranial complications are strongly suspected, or for evaluating specific structures like the optic nerve or cavernous sinus [9]. Advantages include:

- Better differentiation between phlegmon (diffuse inflammation/cellulitis) and drainable abscess.

- Superior visualization of optic nerve inflammation (optic neuritis).

- High sensitivity for detecting early intracranial complications like meningitis (leptomeningeal enhancement), epidural/subdural empyema, brain abscess.

- Excellent evaluation of cavernous sinus pathology (thrombosis, inflammation) - often combined with MR Venography (MRV).

- Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequence is highly sensitive for detecting restricted diffusion within abscess collections (pus), confirming their purulent nature.

- Fundus Photography: Documents optic disc appearance (papilledema, pallor) for baseline and follow-up.

- Ultrasound (Orbital B-scan): Limited role, may sometimes help visualize anterior orbital fluid collections or optic nerve sheath distension, but largely supplanted by CT/MRI.

Clinical findings guide interpretation. Orbital pain worsened by eye movement strongly suggests post-septal involvement (orbital cellulitis/abscess). Visual disturbances (decreased acuity, RAPD, color vision changes, field defects) are critical signs indicating potential optic nerve compromise and often necessitate urgent intervention. Proptosis and ophthalmoplegia indicate significant orbital inflammation or mass effect.

A diagnostic/therapeutic trial involving potent nasal decongestion can sometimes be informative, particularly if optic neuropathy is suspected secondary to posterior sinusitis. Applying a vasoconstrictor (e.g., oxymetazoline or epinephrine 1:1000) combined with a topical anesthetic on pledgets placed in the middle meatus and sphenoethmoidal recess for a period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) aims to shrink inflamed mucosa and potentially relieve pressure near the optic nerve. A documented temporary improvement in visual acuity or color vision after decongestion might suggest a reversible component related to sinus pressure/inflammation, potentially supporting the role of surgical sinus decompression. However, this is not a standard diagnostic test and lack of improvement does not rule out sinus-related optic neuropathy. Formal ophthalmological assessment and imaging remain paramount.

Treatment of Ophthalmic Complications from Sinusitis

Management requires prompt initiation of treatment, typically involving hospitalization and often a multidisciplinary team approach (Otolaryngology, Ophthalmology, potentially Neurosurgery, Infectious Disease, Radiology). Treatment goals are to eradicate the infection, decompress the orbit and optic nerve if vision is threatened, prevent intracranial complications, and restore sinus function.

- Medical Management:

- Antibiotics: High-dose, broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics are the cornerstone of treatment for all suspected infectious orbital complications (orbital cellulitis and beyond require admission and IV therapy; preseptal cellulitis may sometimes be managed outpatient with oral antibiotics if mild and reliable follow-up is possible, but admission is often safer, especially in children) [2, 10].

- Initial empiric therapy should cover common sinus pathogens (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, alpha-hemolytic streptococci, anaerobes).

- Common regimens include: Vancomycin (for MRSA coverage, especially important given increasing prevalence) PLUS a broad-spectrum beta-lactam such as ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ampicillin-sulbactam, or piperacillin-tazobactam.

- Metronidazole is often added for suspected anaerobic involvement (e.g., chronic sinusitis, dental source).

- Coverage should be adjusted based on patient age, local resistance patterns, severity, and potential source (e.g., consider Pseudomonas coverage in nosocomial settings or immunocompromised patients).

- Therapy is tailored based on culture results (from sinuses, blood, or abscess aspirate if obtained).

- Duration is typically prolonged, often 2-4 weeks or longer, usually involving transition to oral antibiotics once significant clinical improvement occurs. Duration guided by clinical resolution and imaging follow-up.

- Nasal Decongestants: Topical vasoconstrictors (e.g., oxymetazoline) should be used for only 3-5 days to avoid rebound congestion. Systemic decongestants (e.g., pseudoephedrine) may offer some benefit but use with caution (side effects). Nasal saline irrigations are helpful to clear secretions and improve drainage.

- Corticosteroids: The role of systemic corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone) is controversial and generally reserved for cases with significant inflammation causing visual threat (optic neuropathy) or severe orbital edema, and only after appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics have been initiated and surgical drainage is not delayed. They can reduce inflammation and edema but may mask worsening infection or impede abscess localization. Contraindicated if fungal infection is suspected. Use requires careful judgment and often consultation between specialists [11].

- Pain Management: Analgesics as needed.

- Antibiotics: High-dose, broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics are the cornerstone of treatment for all suspected infectious orbital complications (orbital cellulitis and beyond require admission and IV therapy; preseptal cellulitis may sometimes be managed outpatient with oral antibiotics if mild and reliable follow-up is possible, but admission is often safer, especially in children) [2, 10].

- Surgical Intervention: Often necessary and urgent, especially for complications beyond simple orbital cellulitis or if vision is compromised [12]. Key indications include:

- Presence of a drainable subperiosteal or orbital abscess confirmed on imaging.

- Lack of clinical improvement (fever, orbital signs) within 24-48 hours of initiating appropriate IV antibiotics.

- Any worsening of vision (acuity, color vision, RAPD development) or persistent visual deficit despite medical therapy.

- Significant proptosis causing optic nerve stretch or exposure keratitis.

- Marked ophthalmoplegia suggesting high orbital pressure.

- Suspicion of anaerobic or fungal sinusitis (requires debridement).

- Presence of intracranial complications (requires neurosurgical involvement).

- Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (ESS): The mainstay approach for most cases today. Allows direct visualization and drainage of infected sinuses (ethmoidectomy, maxillary antrostomy, frontal sinusotomy via Draf procedures, sphenoidotomy) and drainage of most medial or inferior subperiosteal abscesses by carefully removing the lamina papyracea or orbital floor bone overlying the collection. Cultures are taken directly from the sinuses and abscess cavity.

- External Approaches: May be required for abscesses inaccessible endoscopically or if ESS fails. Examples include:

- Lynch incision (medial eyebrow) for medial/superior subperiosteal abscesses.

- Transcaruncular approach (medial canthal) for medial access.

- Subciliary or transconjunctival approach for orbital floor/inferior abscesses.

- Lateral orbitotomy for lateral abscesses.

- External frontoethmoidectomy approaches (less common now).

- Combined endoscopic and external approaches may sometimes be necessary.

Specific Management Notes:

- Preseptal cellulitis: Usually managed medically (often oral antibiotics outpatient if mild, IV if severe or young child), surgery rarely needed unless localized abscess forms in eyelid.

- Orbital cellulitis: Requires admission, IV antibiotics. Close monitoring of vision and orbital signs is essential. Surgery (sinus drainage +/- orbital exploration) is indicated for lack of improvement within 24-48h or any visual decline.

- Subperiosteal abscess: Generally requires urgent surgical drainage (ESS or external) combined with IV antibiotics. Small, medial abscesses in children without visual compromise might occasionally be trialed on IV antibiotics with extremely close monitoring, but surgery is standard.

- Orbital abscess: Requires urgent surgical drainage combined with IV antibiotics.

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis: Requires high-dose IV antibiotics covering likely sources (sinus, face), often anticoagulation (heparin/LMWH initially, though controversial and requires careful risk-benefit assessment, especially regarding intracranial hemorrhage), aggressive management of the primary infection source (surgical sinus drainage if appropriate), and management of potential complications (sepsis, meningitis, stroke).

- Mucoceles/pyoceles: Typically require surgical marsupialization (creating a wide opening into the nasal cavity for drainage) or complete removal with restoration of sinus drainage, usually achieved via ESS. Antibiotics needed for pyoceles.

Close monitoring of visual acuity, color vision, pupillary response, eye movements, and proptosis is essential throughout treatment to detect any deterioration promptly. Regular ophthalmology and otolaryngology follow-up is necessary after discharge.

![]() Attention! Orbital complications of sinusitis are serious and can rapidly lead to permanent vision loss or life-threatening intracranial infections. Symptoms like significant eyelid swelling with eye bulging (proptosis), double vision, pain with eye movement, or any change in vision associated with sinus symptoms require immediate medical evaluation in an emergency setting.

Attention! Orbital complications of sinusitis are serious and can rapidly lead to permanent vision loss or life-threatening intracranial infections. Symptoms like significant eyelid swelling with eye bulging (proptosis), double vision, pain with eye movement, or any change in vision associated with sinus symptoms require immediate medical evaluation in an emergency setting.

References

- Hansen FS, et al. Orbital complications of rhinosinusitis: a population-based study in Denmark, 1997-2017. Rhinology. 2020;58(3):249-256. doi: 10.4193/Rhin19.257

- Wald ER, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e262-80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1071

- Schramm VL Jr, Curtin HD, Kennerdell JS. Evaluation of orbital cellulitis and results of treatment. Laryngoscope. 1982;92(7 Pt 1):732-8. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198207000-00005

- Chandler JR, Langenbrunner DJ, Stevens ER. The pathogenesis of orbital complications in acute sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1970;80(9):1414-28. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197009000-00007

- Rothstein J, Maisel RH, Berlinger NT, Wirtschafter JD. Relationship of optic neuritis to disease of the paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope. 1984;94(11 Pt 1):1501-8. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198411000-00019

- Lee JH, et al. Imaging of the cavernous sinus: a pictorial review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179(6):1581-1588. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791581

- Cannon ML, et al. Cavernous sinus thrombosis complicating sinusitis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5(1):86-8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000104920.13777.41

- Kaplan DM, et al. Orbital and intracranial complications of pediatric sinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2005;38(4):729-39. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2005.03.006

- Yousem DM, Grossman RI. Neuroradiology: The Requisites. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016.

- Chow AW, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):e72-e112. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis370

- Pushker N, et al. Role of Corticosteroids in the Management of Orbital Cellulitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(11):629-633. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.123133

- Garcia GH, et al. Criteria for surgical intervention in pediatric orbital cellulitis. J AAPOS. 2009;13(4):399-403. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.02.013

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)