Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

Colloid Cyst of the Third Ventricle: Overview

A colloid cyst of the third ventricle is a specific type of non-cancerous (benign), epithelial-lined, fluid-filled sac that occurs almost exclusively in a characteristic location within the brain's ventricular system. These cysts represent approximately 0.5-2 percent of all primary intracranial tumors and account for 15-20 percent of intraventricular masses [1, 2]. While histologically benign (WHO Grade I), meaning they do not invade surrounding tissue or metastasize, their critical location can lead to serious, even life-threatening complications due to obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways. They are most commonly diagnosed in adults, typically between the ages of 20 and 50 (peak 3rd-4th decades), although they can be found incidentally or present symptomatically at any age.

Colloid cysts are generally considered congenital, meaning likely present from birth, although they may grow slowly over time. Their origin is debated but thought to relate to abnormal folding of the primitive neuroepithelium during development, possibly derived from remnants of the paraphysis (an embryonic structure near the roof of the diencephalon) or misplaced endodermal cells [3]. Familial cases have been reported, suggesting a potential, though rare, autosomal dominant inheritance pattern in some families [4].

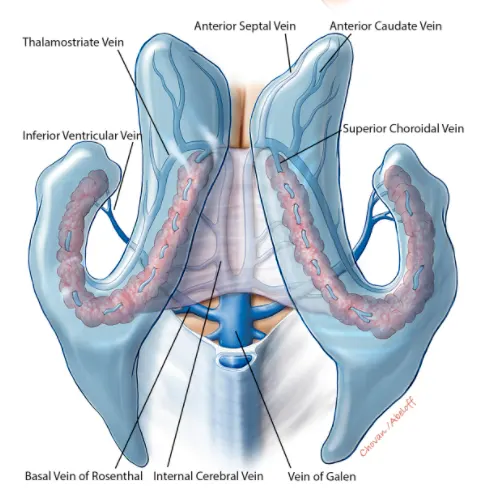

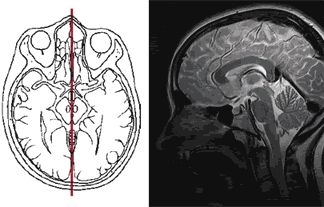

Pathologically, a colloid cyst consists of a thin, fibrous outer capsule lined internally by a single layer of epithelial cells (ranging from simple cuboidal to columnar, occasionally ciliated or mucin-secreting) [5]. These cells secrete the cyst's contents: typically a thick, viscous, gelatinous, proteinaceous material rich in mucin and glycoproteins, sometimes containing old blood breakdown products (hemosiderin), cholesterol crystals, or cellular debris. This dense, protein-rich content is largely responsible for its characteristic hyperdense appearance on CT and often hyperintense signal on T1-weighted MRI. The cyst's hallmark location is in the anterior-superior part of the third ventricle, attached to the roof (tela choroidea/choroid plexus) and situated strategically near or directly within the foramina of Monro – the narrow channels connecting each lateral ventricle to the third ventricle.

This precise location is critical because even relatively small cysts (often 1-2 cm) can act like a ball-valve, intermittently or completely blocking the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from one or both lateral ventricles into the third ventricle, leading to obstructive hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

Colloid Cyst Symptoms

Many colloid cysts (~50% or more in some series) are discovered incidentally on brain imaging performed for unrelated reasons and remain asymptomatic throughout life [6]. However, when symptoms occur, they are primarily related to intermittent or persistent obstruction of CSF flow at the foramina of Monro, leading to hydrocephalus and signs/symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

The most common presenting symptom is headache (~60-70% of symptomatic cases) [7]. This headache is often described as:

- Severe and episodic, rather than constant initially.

- Sometimes positional (characteristically worsened by lying supine or specific head movements that might cause the cyst to shift and acutely block CSF flow, though positional headache is not universally present).

- Occasionally sudden and extremely severe ("thunderclap headache"), mimicking subarachnoid hemorrhage, potentially due to acute blockage.

- May be associated with nausea and vomiting, which are also classic signs of raised ICP.

Other potential neurological symptoms related to hydrocephalus or direct pressure effects include:

- Visual disturbances: Blurred vision, transient visual obscurations (brief dimming/blacking out), or double vision (diplopia due to CN VI palsy from raised ICP). Papilledema (swelling of the optic discs seen on funduscopy) is a key sign of sustained high ICP and can lead to secondary optic atrophy and permanent vision loss if untreated.

- Gait disturbance: Difficulty walking, unsteadiness, imbalance, or ataxia. Part of the classic triad (with dementia and incontinence) seen in normal pressure hydrocephalus, which can sometimes be mimicked or caused by chronic partial obstruction.

- Cognitive changes: Memory impairment (especially short-term memory, potentially related to pressure on the fornices which run near the foramina of Monro), decreased concentration, confusion, personality changes, apathy, lethargy, or altered mental status.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Primarily due to increased ICP.

- Dizziness or Vertigo.

- Seizures: Uncommon, but can occur, possibly due to pressure effects or hydrocephalus.

- Sudden "Drop Attacks": Rare but recognized episodes of abrupt loss of postural tone causing falls without loss of consciousness, potentially related to acute hydrocephalus causing transient brainstem dysfunction.

- Symptoms of Hypothalamic Dysfunction: Very rare, requires large cysts pressing inferiorly; could include endocrine changes or autonomic disturbances.

The most feared complication is acute obstructive hydrocephalus. This can occur suddenly and unpredictably if the cyst completely blocks both foramina of Monro ('ball-valve mechanism'). This constitutes a neurological emergency presenting with sudden severe headache, precipitous vomiting, rapidly declining level of consciousness (stupor, coma), potential pupillary dilation (CN III compression from herniation), posturing, bradycardia, hypertension (Cushing's response), and significant risk of brain herniation (e.g., transtentorial herniation compressing the brainstem). In rare instances (~3-11% of symptomatic cases in older series), this acute obstruction can lead to sudden death, presumably due to acute brainstem compression affecting vital cardiorespiratory centers, or perhaps direct pressure on hypothalamic centers [8, 9].

Colloid Cyst Differential Diagnosis

While colloid cysts have a highly characteristic location (anterior third ventricle roof near foramina of Monro) and often typical imaging features, other lesions can occasionally occur in this region, requiring consideration in the differential diagnosis, especially if imaging is atypical.

Differential Diagnosis of Anterior Third Ventricle / Foramen of Monro Lesions

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Imaging Findings (MRI unless specified) |

|---|---|---|

| Colloid Cyst | Classic location (anterior 3rd ventricle roof @ foramen Monro). Adults usually (20-50). Symptoms of intermittent hydrocephalus (headache +/- positional). Benign. | Well-defined, round. Often hyperdense on CT. MRI: T1 hyperintense (~60-70%), T2 variable (often hypointense). No significant enhancement. No restricted diffusion. +/- Hydrocephalus. |

| Choroid Plexus Papilloma/Carcinoma | Arises from choroid plexus. Papilloma (WHO I) more common in children (lat ventricle trigone); Carcinoma (WHO III) rarer. Can occur in 3rd ventricle. Often causes hydrocephalus (overproduction or obstruction). | Lobulated, "frond-like" intraventricular mass. T1 iso/hypo, T2 iso/hyper. Intense, often homogeneous enhancement. Calcification/hemorrhage possible. |

| Subependymoma | Benign (WHO I), slow-growing glial tumor from subependymal zone. Older adults often (>40). Common near foramen Monro (also 4th ventricle). Often incidental or causes hydrocephalus if large. | Lobulated intraventricular mass, often attached to septum pellucidum/wall. T1 hypo/iso, T2 markedly hyperintense. Typically minimal or no contrast enhancement. Small cysts/calcification/hemorrhage possible. |

| Central Neurocytoma | Rare neuronal tumor (WHO II). Young adults (20s-40s). Usually lateral ventricle near foramen Monro, often attached to septum pellucidum, can involve/extend into 3rd. Hydrocephalus common. | Often lobulated intraventricular mass with cystic components ("bubbly" appearance). T1 iso, T2 iso/hyper. Moderate, often heterogeneous enhancement. Calcification frequent (~50%). |

| Subependymal Giant Cell Astrocytoma (SEGA) | Benign tumor (WHO I), pathognomonic for Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC). Children/young adults. Arises near foramen Monro from ventricular wall. Progressive hydrocephalus is common presentation. | Well-defined mass near foramen Monro, often >1cm. T1 iso/hypo, T2 iso/hyper (variable). Intense enhancement after contrast. Calcification common. Look for other stigmata of TSC (cortical tubers, subependymal nodules). |

| Intraventricular Meningioma | Rare (<5% of meningiomas). Arises from arachnoid cap cells within choroid plexus or tela choroidea. Usually lateral ventricle trigone, but can occur in 3rd. Adults, F>M. | Well-defined, lobulated intraventricular mass. T1/T2 isointense to grey matter. Intense, usually homogeneous enhancement. May have calcification. No connection to dura. |

| Craniopharyngioma (Intraventricular extension) | Primarily suprasellar tumor, but adamantinomatous type (children) can extend superiorly into 3rd ventricle. Visual/endocrine symptoms common. | Complex cystic (often T1 bright from protein/cholesterol) and solid mass with calcification (CT best) and nodular/rim enhancement. Epicenter usually suprasellar. |

| Epidermoid Cyst | Congenital inclusion cyst containing keratin debris. Rare in 3rd ventricle, more common CPA/suprasellar. Slow growing. | Lobulated mass, insinuates into CSF spaces. T1 hypo, T2/FLAIR hyper (CSF-like but slightly "dirty"). Restricted diffusion (DWI bright, ADC dark) is key diagnostic feature. Minimal/no enhancement (thin rim possible). |

| Basilar Tip Aneurysm | Large aneurysm at top of basilar artery can project superiorly into interpeduncular cistern/floor of 3rd ventricle. Risk of SAH. | MRI may show flow void, complex signal with thrombus. MRA/CTA/DSA confirms vascular nature and defines aneurysm anatomy. |

| Neurocysticercosis (Intraventricular) | Parasitic cyst (larval stage of Taenia solium tapeworm). Can lodge freely or attached in 3rd ventricle (or 4th/lateral), causing obstructive hydrocephalus. Endemic area history relevant. | Appearance varies with stage. Vesicular stage: thin-walled cyst, CSF signal, often contains small enhancing scolex (dot), minimal/no wall enhancement. Degenerating stages (colloidal, granular) show ring enhancement and edema. |

| Arachnoid Cyst (Suprasellar extending into 3rd V) | Congenital CSF-filled cyst. Can occur in suprasellar cistern and extend upwards, potentially obstructing foramina. Usually asymptomatic unless large. | Well-defined cyst following CSF signal intensity on ALL sequences (T1 low, T2 high, FLAIR suppressed). Thin, imperceptible wall, no enhancement, no restricted diffusion. Displaces adjacent structures. |

Careful analysis of imaging characteristics (precise location, shape, signal intensity on different MRI sequences - especially T1 pre-contrast, T2, FLAIR, DWI, presence/pattern of enhancement) combined with clinical presentation and patient demographics usually allows confident differentiation of colloid cysts from these other possibilities.

Colloid Cyst Diagnosis

Neuroimaging is the cornerstone for diagnosing colloid cysts. These cysts have characteristic features on both CT and MRI that usually allow for a confident diagnosis.

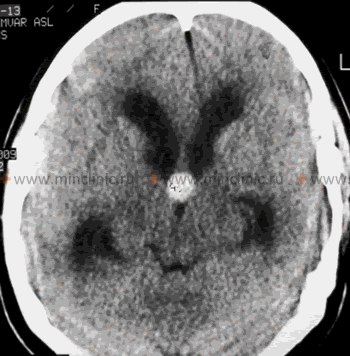

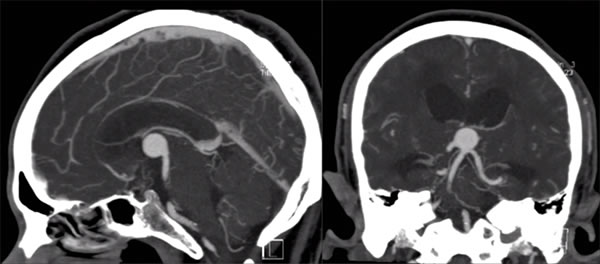

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: On non-contrast CT scans, colloid cysts typically appear as well-circumscribed, round or oval masses located in the classic position at the anterior third ventricle near the foramina of Monro. They are characteristically hyperdense (appearing brighter than surrounding brain tissue) in about two-thirds of cases due to their high protein and cholesterol content [1]. In the remaining third, they may be isodense or, rarely, hypodense relative to brain. Calcification within the cyst is uncommon. After contrast administration, there is usually no significant enhancement of the cyst itself, although a thin, faint rim enhancement of a displaced choroid plexus or compressed capsule is occasionally seen. CT readily demonstrates the presence and degree of associated hydrocephalus (enlargement of the lateral ventricles).

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI provides superior soft tissue detail and is considered the preferred modality for characterizing colloid cysts and their relationship to adjacent structures [10]. The signal characteristics can vary depending on the specific composition (hydration state, concentration of protein, cholesterol, paramagnetic ions like manganese) of the cyst contents:

- T1-weighted images: Most commonly appear hyperintense (bright) relative to brain parenchyma (~60-70% of cases), a key distinguishing feature. However, they can also be isointense or hypointense, especially if less proteinaceous.

- T2-weighted images: Signal intensity is highly variable and less predictable. Many are hypointense (dark) relative to brain tissue and CSF, thought to be due to the thick, gelatinous nature of the contents. However, they can also be isointense or hyperintense (bright). This variability can sometimes make diagnosis challenging based on T2 alone.

- FLAIR (Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery) images: Signal is also variable, often mirroring T2 intensity but suppressing surrounding CSF signal. FLAIR is excellent for visualizing subtle periventricular edema (bright signal adjacent to ventricles) indicative of transependymal CSF flow in acute or subacute hydrocephalus.

- Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI): Colloid cysts typically do not show restricted diffusion (i.e., they are not bright on DWI and not dark on ADC maps), which helps differentiate them from lesions containing highly cellular material or viscous pus like epidermoid cysts or abscesses.

- Contrast Enhancement (Gadolinium): Colloid cysts themselves are avascular and generally do not enhance internally. A thin, smooth peripheral rim of enhancement might sometimes be seen, likely representing compressed, enhancing choroid plexus or a thin reactive fibrous capsule, but prominent or nodular enhancement should raise suspicion for an alternative diagnosis [11].

- Cerebral Angiography (CTA/MRA/DSA): Generally not required for diagnosis of typical colloid cysts but may be considered to rule out vascular lesions like a basilar tip aneurysm if the imaging appearance on standard CT/MRI is atypical or inconclusive.

The combination of the classic location (midline, anterior third ventricle roof at foramina of Monro), typical hyperdensity on non-contrast CT, characteristic signal intensities on MRI (often T1 bright, T2 dark/variable, non-enhancing, no restricted diffusion), and presence of associated hydrocephalus usually allows for a highly confident radiological diagnosis of a colloid cyst.

Colloid Cyst Treatment

The management strategy for a colloid cyst depends primarily on the presence and severity of symptoms, the size of the cyst, the degree of associated hydrocephalus, and patient-specific factors like age and overall health. Treatment options range from observation to surgical intervention [12].

- Asymptomatic Cysts: Small (< 1.0 cm), incidentally discovered colloid cysts without evidence of hydrocephalus may be managed conservatively with serial neuroimaging (MRI preferred) to monitor for stability, typically every 6-12 months initially, then less frequently if stable [7, 6]. However, due to the small but real risk (~0-1% per year risk debated) of sudden neurological deterioration or death even with previously asymptomatic cysts, some centers advocate for prophylactic surgical resection, particularly if the cyst is larger (e.g., >1.0-1.5 cm) or if the patient is young and has a long life expectancy. The optimal management of asymptomatic cysts remains debated, and the decision requires careful discussion between the patient and the neurosurgical team regarding risks and benefits [13].

- Symptomatic Cysts: Patients experiencing symptoms clearly attributable to the colloid cyst (e.g., headaches characteristic of raised ICP, visual changes with papilledema, cognitive issues, documented hydrocephalus) generally require definitive treatment, which is typically surgical removal.

- Acute Hydrocephalus: Patients presenting with acute obstructive hydrocephalus and rapid neurological decline require emergency management. This usually involves immediate placement of an external ventricular drain (EVD) to relieve the dangerously high intracranial pressure by draining CSF externally. Once the patient is stabilized, definitive cyst removal is typically performed urgently or semi-urgently.

Neurosurgical Treatment Options for Colloid Cysts:

- Endoscopic Resection: This is often considered the first-line minimally invasive approach for many colloid cysts today [14]. Performed through a small burr hole and trajectory into the lateral ventricle, an endoscope (a thin tube with a camera and working channels) is guided to the foramen of Monro. Instruments passed through the endoscope are used to open the cyst wall, aspirate the thick contents, and then remove or coagulate the cyst wall remnants. Advantages include smaller incision, less brain retraction, potentially shorter hospital stay, and effectiveness in relieving hydrocephalus. Complete removal of the cyst wall can sometimes be challenging endoscopically, leading to a small risk of recurrence, though rates are generally low with experienced surgeons.

- Microsurgical Resection (Open Craniotomy): This involves a formal craniotomy (opening the skull) to access the third ventricle. Common approaches include:

- Interhemispheric Transcallosal Approach: Accessing the roof of the third ventricle by carefully splitting the corpus callosum (the fibers connecting the two brain hemispheres) in the midline. Provides wide visualization of the cyst, fornices, and internal cerebral veins, facilitating complete removal of the cyst and its wall. Considered the gold standard by many for achieving complete resection, especially for larger cysts.

- Transcranial Transcortical Approach: Accessing the lateral ventricle through a small incision in the cerebral cortex (often non-dominant frontal lobe) and then navigating through the foramen of Monro to reach the third ventricle and the cyst. May involve slightly more brain transgression than the transcallosal route.

- Stereotactic Aspiration: Using image guidance to place a needle into the cyst and aspirate its contents without direct visualization or wall removal. This is rarely used now as a primary definitive treatment due to very high recurrence rates (~50% or more) as the secreting epithelial lining is left behind. It might be considered only as a temporizing measure or in patients deemed unfit for more definitive endoscopic or open surgery [15].

- CSF Shunting (Ventriculoperitoneal [VP] Shunt): Placement of a shunt system to drain excess CSF from the lateral ventricles to another body cavity (usually the peritoneum) can effectively treat the hydrocephalus caused by the cyst. However, it does not address the cyst itself or eliminate the risk of sudden death from acute cyst enlargement or blockage. Shunting is generally reserved only for patients who are poor surgical candidates for cyst resection or as a temporizing measure before definitive surgery [12].

Surgical resection, particularly aiming for complete removal via either endoscopic or microsurgical techniques by experienced neurosurgeons, offers the best chance for long-term cure and resolution of symptoms. Success rates for symptom relief and hydrocephalus resolution are high (>90%) in experienced hands. However, surgery carries potential risks, including damage to surrounding critical structures like the fornices (memory circuits), thalamus, hypothalamus, internal cerebral veins (risk of venous infarction), as well as general surgical risks like hemorrhage, infection (meningitis, ventriculitis), seizures, or CSF leak. The reported rates of significant complications are generally low (e.g., <5-10%) at specialized centers [7].

![]() Attention! Colloid cysts, while benign, can cause serious neurological problems including sudden deterioration due to acute hydrocephalus. Symptoms like severe, intermittent, or positional headaches, visual disturbances, gait problems, or sudden collapse require prompt medical evaluation, including neuroimaging. Management decisions should be made in consultation with experienced neurosurgeons and neurologists.

Attention! Colloid cysts, while benign, can cause serious neurological problems including sudden deterioration due to acute hydrocephalus. Symptoms like severe, intermittent, or positional headaches, visual disturbances, gait problems, or sudden collapse require prompt medical evaluation, including neuroimaging. Management decisions should be made in consultation with experienced neurosurgeons and neurologists.

References

- Melmed S. Pituitary-Tumor Endocrinopathies. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 5;382(10):937-950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810772

- Camacho A, et al. Colloid cysts: a review including pathogenesis, pathology, behavior, and treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;17(4):E6. doi: 10.3171/foc.2004.17.4.6

- Lach B, et al. Colloid cyst of the third ventricle. A comparative immunohistochemical study of choroid plexus and ependyma. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(1):101-11. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.1.0101

- Partington MW, et al. Familial colloid cysts of the third ventricle. Am J Med Genet. 1999;85(4):368-74. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990730)85:43.0.co;2-5

- Ho KL, Garcia JH. Colloid cysts of the third ventricle: ultrastructural features are compatible with endodermal derivation. Acta Neuropathol. 1992;83(6):605-12. doi: 10.1007/BF00296727

- Pollock BE, et al. Natural history of colloid cysts of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg. 1997;87(1):10-14. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.1.0010

- Beaumont TL, et al. Colloid Cysts of the Third Ventricle: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Treatment Approaches. World Neurosurg. 2016;92:32-42. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.04.058

- Ryder JW, et al. Sudden deterioration and death in patients with benign tumors of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg. 1986;64(2):216-23. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.2.0216

- Büttner A, et al. Colloid cyst of the third ventricle with sudden death: a forensic autopsy case. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42(3):530-3.

- Armao D, et al. Colloid cyst of the third ventricle: imaging-pathologic correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(8):1470-7.

- Wilms G, et al. CT and MR imaging of the normal and diseased third ventricle. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(12):2436-44. doi: 10.1007/s003300100943

- Spears J. Colloid Cysts. In: Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol 169 (3rd series) Neuro-oncology, Part 1. Elsevier; 2020: 261-271. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-822198-3.00048-7

- Nakaji P, et al. Natural history and surgical management of colloid cysts of the third ventricle. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(3):577-85; discussion 585. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000290911.61779.6E

- Horn EM, et al. Treatment options for colloid cysts of the third ventricle. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(4):E6. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.23.4.7

- Mathiesen T, et al. High recurrence rate following aspiration of colloid cysts in the third ventricle. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(7):761-4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.7.761

- Osborn AG, Salzman KL, Jhaveri MD, et al. Osborn's Brain. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 9th ed. Thieme; 2020.

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)