Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Clinical Manifestations of Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy):

- Differential Diagnosis of Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Clinical Examination for Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Treatment and Management of Patients with Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Medication Therapy for Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Follow-up Monitoring of Patients with Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

Origin

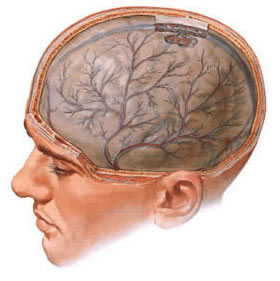

Corticobasal ganglionic degeneration or limited brain atrophy is a sporadic neurodegenerative tauopathy, which can be considered both as a syndrome of characteristic motor and cognitive dysfunction (corticobasal syndrome) and as a specific pathological condition (disease). Corticobasal syndrome is characterized by progressive dementia, parkinsonism, and limb apraxia, which can also result from a range of pathological conditions. The most characteristic complex disorder is similar to Pick's disease, but manifestations similar to Alzheimer's disease and even rare CNS disorders like Whipple's disease and Niemann-Pick type C disease can also be associated with corticobasal syndrome. Histopathologically identified corticobasal ganglionic degeneration can also manifest clinically as primary progressive aphasia or primary progressive apraxia in patients who previously had no known motor disorders in life.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiological examination reveals both cortical and subcortical types of abnormalities. The disorder is currently classified as a 4-repeat (4R) tauopathy. Tau-immunoreactive neuronal and glial inclusions can also be seen in Pick's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and even Alzheimer's disease. These disorders may differ in the proportions between microtubule-associated 4- and 3-repeat isoforms of tau protein. In corticobasal ganglionic degeneration and PSP, predominantly 4R tauopathies are identified. Both neurons and glial cells are involved in the pathological process – cortical (pyramidal and non-pyramidal) neurons, as well as neurons in subcortical regions. Spherically swollen neurons with loss of cytoplasmic staining (achromasia) found in the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia also provide diagnostic assistance. Corticobasal ganglionic degeneration may be associated with loss of cortical and subcortical neurons, neuronal and glial tauopathy (including astrocytic plaques). Thinning of the cerebral cortex, predominantly in the motor and premotor areas, helps distinguish this disease from PSP.

Epidemiology

Frequency: Data on the incidence and prevalence of this disorder are still being collected. Clinical reports have multiplied exponentially over the last 20 years, suggesting that either clinical assessment has become more sensitive, or the syndrome has become more common. The disease frequency is about 5% of parkinsonism cases identified in clinics specializing in motor disorders, corresponding to 0.02-7.3 cases per 100,000 population per year in the US, Western Europe, and Asian countries.

Mortality/Morbidity: This is a progressive neurodegenerative disease with a subsequent increase in the degree of patient disability and loss of ability for self-care. Individuals with corticobasal ganglionic degeneration usually die not from the disorder itself, but from its complications that arise in bedridden patients (such as aspiration pneumonia and infections) within 10 or more years from the onset of the disease.

Race: Racial predisposition to the disease is unknown.

Sex: Several studies have identified corticobasal ganglionic degeneration more frequently in women.

Age: Typically, corticobasal ganglionic degeneration occurs in patients aged between 50 and 80 years. There are no published pathologically confirmed cases of corticobasal ganglionic degeneration with disease onset before age 45. There is a case history of a patient who died with pathologically confirmed corticobasal ganglionic degeneration whose first symptoms appeared at age 41, and a case history of a patient with onset of corticobasal syndrome at age 28.

Clinical Manifestations of Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

Medical History

Boeve et al. describe the following clinical symptoms as part of the phenotypic syndromes of corticobasal ganglionic degeneration:

- Gradual onset and progressive course

- No clearly defined alternative causes (stroke, tumor, etc.)

- Cortical dysfunction, including at least 1 of the following symptoms:

- Focal or asymmetric ideomotor apraxia – a disorder of skilled, acquired, and purposeful movements; this is one of the few disorders where limb apraxia may be present in the patient's medical history

- Alien limb phenomenon ("my hand/leg has a mind of its own")

- Cortical (parietal lobe) sensory loss

- Reduced visual or tactile spatial perception

- Constructional apraxia

- Focal or asymmetric myoclonus

- Apraxia of speech or non-fluent aphasia

- Extrapyramidal dysfunctions, including at least 1 of the following symptoms:

- Focal or asymmetric appendicular rigidity (unresponsive to levodopa)

- Focal or asymmetric appendicular dystonia

- In some cases accompanied by depression and postural instability

- Unusual manifestations, e.g., primary progressive aphasia and progressive buccofacial apraxia

- The presence of delusions and hallucinations (not related to levodopa) suggests that the patient does not have corticobasal ganglionic degeneration; they are more characteristic of diffuse Lewy body disease

Patient Examination

During the patient examination, pay attention to the following:

- Limb apraxia: patients may make errors when using parts of their body as tools (e.g., using fingers as scissor blades). Errors often indicate ideomotor or motor limb apraxia.

- Other cognitive impairments, which include the following:

- amnesia

- often, not "cognitive" abnormalities (e.g., right-left disorientation, difficulty naming objects, calculation disorder – acalculia), but rather "frontal executive" deficits (e.g., increased distractibility, perseveration, loss of judgment, reduced ability to perform planned movements even on the less affected side)

- Eye movements may be impaired: limitation of horizontal movement, as well as upward gaze; limitation of downward gaze suggests progressive supranuclear palsy.

- Dystonia: not purely provoked by motor activity.

- Myoclonus: myoclonus can spread beyond the fingers if it is stimulus-sensitive.

- Rigidity: easily elicited without additional effort.

- Rest tremor is absent.

- Autonomic disturbances are absent.

- Cortical sensory loss: loss of graphesthesia (the ability to identify letters written on the skin of the hands or fingers with a light touch) can be a sensitive test.

- Loss of proprioceptive sense is not part of the syndrome; rather, such movement disorders may be related to peripheral nerve pathology (neuropathy).

Causes of the Disease

- The etiology of corticobasal ganglionic degeneration is unknown.

- Described cases suggest that there may be a familial predisposition in some individuals with this disorder.

- Due to the close clinical and pathological relationships between corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, and Pick's disease, attention in this disease focuses on the genetic basis of 4-repeat tauopathy to identify individuals susceptible to this pathology and potential target molecules for treatment. Currently, however, there is no identified relationship between clinically available genetic markers and corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, although the microtubule-associated tau protein (MAPT) gene is significant in this and other neurodegenerative diseases related to tauopathy (progressive supranuclear palsy, Pick's disease/frontotemporal dementia).

- Limb apraxia and the appearance of eye movement abnormalities are highly likely related to structural changes in the cortex of the left hemisphere.

Differential Diagnosis of Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

Differential diagnosis is conducted between the following diseases affecting the central nervous system:

- Alzheimer's disease

- Stroke in the internal carotid artery territory

- Apraxia and related syndromes

- Whipple's disease

- Cardioembolic stroke

- Chronic myeloid leukemia

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Focal epilepsy

- Frontal lobe syndromes (primary progressive aphasia and primary progressive apraxia)

- Frontotemporal dementia and frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- Glioblastoma multiforme

- Huntington's disease

- Hydrocephalus

- Marchiafava-Bignami disease

- Multiple System Atrophy

- Neuroacanthocytosis

- Neuroacanthocytosis syndromes

- Neurosyphilis

- Olivopontocerebellar atrophy

- Parkinson's disease

- Parkinsonism syndromes

- Pick's disease

- Progressive supranuclear palsy

- Striatonigral degeneration

- Subdural hematoma

- Thalamic stroke

- Neurological diseases associated with vitamin B12 deficiency

- Neurological diseases associated with vitamin E deficiency

- Wilson's disease

Clinical Examination for Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

Laboratory Studies

Types of laboratory studies:

- Ceruloplasmin – tested in patients with atypical parkinsonism and parkinsonian syndromes

- Tests for reversible systemic factors causing cognitive deficits:

- Vitamin B12 level

- Anticardiolipin antibodies / Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test – may be false positive in patients over 65 years old; performed to exclude neurosyphilis

- Thyroid function tests, thyroid autoantibody screening

- Electrolytes

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential and platelet count

- If necessary or other confirmation of systemic diseases – rheumatological studies, including antinuclear antibodies (ANA), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), liver function tests, and ammonia level

- Peripheral blood smear for acanthocytosis or genetic testing for Huntington's disease if the patient has chorea

Imaging Studies

Types of imaging studies:

- Brain MRI

- This study is particularly useful in assessing the size and appearance of the midbrain if there is any eye movement disorder and progressive supranuclear palsy is suspected. Midbrain size should be relatively normal in corticobasal ganglionic degeneration.

- Cortical atrophy usually occurs and may be localized (often asymmetrically) in the frontoparietal regions, including the central sulcus/supplementary motor area and superior frontal gyrus, rather than predominantly in the temporoparietal cortex (which is more characteristic of dementia in Alzheimer's disease).

- Abnormal signals in the basal ganglia may occur with metal deposition in Wilson's disease or neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (formerly Hallervorden-Spatz disease).

- Functional brain imaging (e.g., PET, SPECT) is usually not required for diagnosis but may be useful in some patients to confirm that cognitive changes are neurological (organic) rather than psychological. Positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can help identify asymmetry in metabolic activity or perfusion in cortical (frontoparietal) and subcortical (basal ganglia, thalamus) regions.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is performed when limited brain atrophy is suspected.

Other Tests

- Neuropsychological testing or assessment of limb apraxia by a neuropsychologist, speech therapist, or rehabilitation specialist qualified and experienced in working with patients with neurodegenerative disorders is recommended. This can help differentiate these patients from those with a combination of parkinsonism and Alzheimer's disease, who may also have apraxia but typically lack such significant motor coordination impairment or the alien limb phenomenon.

- Electroencephalography (EEG) may be considered in cases of prominent myoclonus or episodes suggesting seizures or rapid decline in muscle tone, although it is often normal or shows nonspecific slowing.

- Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) are generally not part of the standard clinical workup. If performed as part of research on reflex myoclonus, they typically do not show giant potentials characteristic of cortical myoclonus seen in some other conditions.

Diagnostic Procedures

In patients with pronounced segmental myoclonus (especially facial), eye movement disorders, a history of aphthous ulcers, chronic diarrhea, or arthritis of unknown origin, the following diagnostic procedures may be used to rule out CNS involvement by Whipple's disease:

- Lumbar puncture may be performed to examine cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for cell count, protein levels; polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for Tropheryma whipplei should also be done if Whipple's disease is suspected. CSF analysis is usually normal in corticobasal degeneration.

- Jejunal biopsy is performed if Whipple's disease involving the gut is suspected; it can show characteristic changes.

- Brain biopsy is rarely performed for diagnosis due to its invasive nature but might be considered in atypical cases where diagnostic certainty is crucial (e.g., distinguishing from potentially treatable conditions or for research/familial counseling).

Histological Findings

In the frontoparietal cortex, findings include neuronal loss, gliosis (particularly astrogliosis with characteristic astrocytic plaques), neuropil threads, and sometimes neurofibrillary tangles. The presence of swollen, achromatic neurons (ballooned neurons or Pick-like cells) is characteristic. Argyrophilic, tau-immunoreactive inclusions (neuronal and glial) are found subcortically in the substantia nigra (where neuronal loss is also noted), basal ganglia, thalamus, and dentate nucleus/pathways. Although the overall histological pattern differs from progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), the tau-positive inclusions in corticobasal degeneration are primarily composed of 4-repeat (4R) tau isoforms, similar to PSP. Some morphological overlap exists, such as coiled bodies in oligodendrocytes, making definitive distinction occasionally challenging based solely on histology, although astrocytic plaques are more specific to corticobasal degeneration pathology.

Stages of the Disease

Currently, specific staging based on histopathological findings correlated with clinical progression is not well-established for routine clinical use. The disease progresses over time, with an average duration from onset to death typically around 7-8 years, though variability exists.

Treatment and Management of Patients with Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

Treatment Recommendations

- At the initial evaluation, review and potentially discontinue anticholinergic or other medications that may worsen cognitive function or attention. Discontinue any medications that could cause secondary parkinsonism. Consider antioxidants like vitamin E, although evidence for efficacy is limited. Initiate empirical treatment for depression if present. Conduct a trial of levodopa/carbidopa (e.g., Sinemet) if rigidity or bradykinesia is prominent, titrating the dose adequately (e.g., up to 1000-1500 mg/day of levodopa) before concluding non-responsiveness, though response is typically poor or absent in corticobasal degeneration. Recommend botulinum toxin injections if painful focal dystonia (e.g., in a limb) is present. If prominent myoclonus or episodes of loss of tone occur, consider electroencephalography (EEG). Refer the patient for consultation with rehabilitation specialists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists as needed for assessment of gait, fall risk, assistive device needs, home safety, speech/swallowing difficulties, and development of programs to maintain endurance, strength, and functional independence.

- On follow-up visits, manage any identified systemic comorbidities. If the levodopa/carbidopa trial was clearly ineffective, discontinue it. Consider empirical trials of other dopaminergic agents (agonists), though benefit is unlikely. Consider treatment with clonazepam or levetiracetam for bothersome myoclonus. Reconsider lumbar puncture if symptoms suggestive of treatable conditions like Whipple's disease emerge; discuss risks/benefits with the patient and family. If dementia is progressing, ensure appropriate support services are in place (e.g., home health aide, social worker referral, caregiver support). Provide educational materials about corticobasal degeneration and dementia to the patient and family. Arrange consultations with neuropsychology or rehabilitation specialists for strategies to manage cognitive and motor impairments, if desired.

- At later visits, continue managing systemic issues. Reconsider diagnostic procedures like lumbar puncture or, rarely, brain biopsy if the diagnosis remains uncertain and clarification would significantly alter management or provide crucial prognostic/genetic information for the family. Continue symptomatic management, adjusting therapies like botulinum toxin or anti-myoclonus medications based on clinical response and side effects. Focus increasingly on supportive care, safety, and quality of life.

Consultations

- Physical therapist and rehabilitation specialist: Physical therapy and rehabilitation can be helpful for maintaining mobility and endurance, managing gait disturbances, preventing falls, and teaching compensatory strategies for activities of daily living affected by apraxia or motor deficits. Occupational therapy can address difficulties with fine motor tasks and adaptive equipment.

- Speech therapist: Can evaluate and manage speech disorders (apraxia of speech, dysarthria, aphasia) and swallowing difficulties (dysphagia). They can teach compensatory strategies and recommend assistive communication devices if needed, similar to those used in ALS. Early intervention is beneficial while learning capacity remains. A specially trained speech therapist can also formally assess apraxia using standardized tests if diagnosis is uncertain.

- Geriatrician, palliative care specialist, visiting nurse, or social worker: Can be invaluable in counseling patients and families regarding prognosis, advance care planning, quality of life issues, caregiver support, and navigating resources for long-term care and patient care rules.

- Neuropsychologist: Can provide detailed cognitive assessment, help differentiate cognitive profiles, and offer strategies for managing cognitive and behavioral changes. Counseling can support patients and families in coping with the diagnosis.

- Movement disorder specialist/Neurologist: Provides primary diagnosis and ongoing management. May facilitate participation in research studies, brain donation programs, or genetic counseling if appropriate and desired by the patient/family.

Diet

- Patients with significant buccofacial apraxia or motor dysfunction may develop dysphagia (swallowing difficulties).

- Consultation with a speech therapist is recommended for formal swallowing evaluation (e.g., modified barium swallow study) if dysphagia is suspected.

- Diet modifications (e.g., thickened liquids, soft/pureed foods) may be necessary depending on the severity of swallowing impairment to prevent aspiration.

- Constipation, common due to immobility and autonomic dysfunction, should be managed proactively with increased fluid intake, dietary fiber, physical activity encouragement, and stool softeners or laxatives as needed.

Physical Activity

Physical activity is generally encouraged within the patient's limits to maintain function and well-being, but assistance and safety precautions become increasingly necessary as the disease progresses due to motor deficits, imbalance, and fall risk.

Medication Therapy for Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

Unfortunately, there are currently no disease-modifying treatments proven to slow or reverse the progression of corticobasal ganglionic degeneration. Management is focused on symptomatic relief. Cholinesterase inhibitors might be considered for primary progressive aphasia presentations, given some evidence in other tauopathies, but efficacy is uncertain. Medications used for Parkinson's disease, including anticholinergics (generally avoided due to cognitive side effects), levodopa, and dopamine agonists, typically provide little to no benefit for the motor symptoms of corticobasal degeneration but are often trialed.

Overview of Medications Used

These drugs aim to supplement dopamine or stimulate dopamine receptors.

An NMDA receptor antagonist, sometimes considered for cognitive symptoms in dementia, but its role in corticobasal degeneration is not established. It is not primarily dopaminergic. [Note: The original Russian text described it inaccurately as having nootropic, myotonolytic, dopaminergic, and glutamatergic effects relevant here].

Levodopa/carbidopa (e.g., Sinemet)

A lack of significant or sustained positive response to an adequate trial of levodopa is characteristic of corticobasal degeneration and helps differentiate it from Parkinson's disease. However, a trial is often warranted. Gradual dose titration (e.g., up to at least 1000 mg levodopa per day) is necessary.

An older ergot-derived dopamine agonist (D2 agonist, partial D1 agonist). Stimulates dopamine receptors in the striatum. Generally not effective in corticobasal degeneration and carries risks (e.g., fibrosis). Newer non-ergot agonists are preferred if an agonist trial is considered.

Absorption is partial (approx. 28%), metabolized by the liver, long half-life (approx. 50 h), primarily excreted in feces. Start low, titrate slowly. Levodopa dose might be reduced initially if used concurrently.

Evaluate effectiveness periodically. Reduce dose if significant side effects occur.

A non-ergot dopamine agonist. Often ineffective for corticobasal degeneration symptoms, but occasionally trialed, particularly if rigidity is prominent, though benefit is rare.

A non-ergot dopamine agonist with higher affinity for D2/D3 receptors. May stimulate dopaminergic activity in the striatum and substantia nigra. Often ineffective in corticobasal degeneration but sometimes trialed.

Mechanism complex, may involve enhancing dopamine release, blocking dopamine reuptake, and NMDA receptor antagonism. Occasionally used for parkinsonism or dyskinesia (less relevant here). Limited efficacy in corticobasal degeneration.

There are no proven neuroprotective therapies to slow brain atrophy in corticobasal ganglionic degeneration. While some agents are studied in other neurodegenerative dementias, their use here is empirical and generally not supported by strong evidence.

An antioxidant. May protect polyunsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes from free radical damage. Large trials in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease have yielded mixed or negative results regarding disease modification. Its role in corticobasal degeneration is unproven.

Possess analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic activity. Their mechanism involves inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes and thus prostaglandin synthesis. Other potential effects exist. Used for pain relief, not for disease modification in neurodegeneration.

Epidemiological studies suggested long-term NSAID use might reduce Alzheimer's risk, but clinical trials have not shown benefit for prevention or treatment. Not indicated for corticobasal degeneration itself, only for coincidental pain/inflammation.

Can help manage myoclonus. These drugs bind to specific benzodiazepine receptors, enhancing the inhibitory effects of the neurotransmitter GABA.

Often used as a first-line agent for myoclonus. One study [citation needed/details vague] reported reduction in severe myoclonus in 23% of patients [context unclear if specific to CBD]. It suppresses muscle contractions by potentiating GABAergic inhibition. Use with caution due to sedation, cognitive dulling, and fall risk, especially in the elderly or those with dementia.

Botulinum toxin injections can be effective for managing focal dystonia, particularly if it is painful or interferes significantly with function. It acts by inhibiting acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction.

Botulinum Toxin Type A (e.g., Botox, Dysport, Xeomin)

Effective for treating excessive and abnormal muscle contractions in focal dystonia. Binds to presynaptic nerve terminals at the neuromuscular junction, is internalized, and cleaves SNARE proteins, thereby blocking acetylcholine release and causing localized muscle weakness/paralysis.

Reassessment typically occurs several weeks (e.g., 2-4 weeks) after injection to evaluate efficacy, with peak effect often around 4-6 weeks and duration typically 3-4 months.

Dosing is individualized based on the muscles involved, severity, and prior response. Doses are measured in units specific to the formulation (e.g., Botox units). Repeat injections are needed to maintain effect. Maximum doses per session exist to minimize risk of systemic spread.

May be considered empirically in patients presenting with primary progressive aphasia variants, although evidence specifically for corticobasal degeneration is limited. These drugs increase acetylcholine levels by inhibiting its breakdown.

Galantamine is a reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and also modulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. By inhibiting cholinesterase, it increases synaptic acetylcholine levels, potentially enhancing cholinergic neurotransmission. Primarily used for Alzheimer's disease dementia. There is no strong evidence that cholinesterase inhibitors alter the underlying disease process in tauopathies like corticobasal degeneration.

Follow-up Monitoring of Patients with Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

Further Outpatient Treatment

Periodic follow-up visits are necessary to monitor disease progression, adjust symptomatic therapies (e.g., for dystonia, myoclonus), manage complications (e.g., falls, infections, dysphagia), address depression or other behavioral symptoms, and provide ongoing support and education to the patient and caregivers. The plan of care needs regular adjustment as the patient's functional abilities decline.

Further Inpatient Treatment

Hospitalization may be required for managing acute complications (e.g., aspiration pneumonia, severe infections, fall-related injuries) or for procedures like feeding tube placement if dysphagia becomes severe. Admission solely for diagnostic acceleration is uncommon. Brain biopsy, if considered, is typically performed in specialized centers, usually after extensive non-invasive workup.

Complications

Potential complications of the disease include falls and related injuries, dysphagia leading to aspiration pneumonia and malnutrition, immobility leading to pressure sores, deep vein thrombosis, and contractures, infections (especially respiratory and urinary tract), depression, anxiety, and caregiver burnout. Subdural hematoma is a rare but recognized risk following lumbar puncture, particularly in patients with brain atrophy; monitoring for headache, drowsiness, or mental status changes post-procedure is prudent.

Prognosis

Unfortunately, corticobasal ganglionic degeneration is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder leading to increasing cognitive and motor disability. The average survival time from symptom onset is typically around 7-8 years, but the course can vary.

The cause of death is usually related to complications of immobility and advanced disease, such as aspiration pneumonia, sepsis, or pulmonary embolism, rather than the primary neurodegeneration itself.

Patient Education

- Consultation with a geriatrician or palliative care specialist can be very helpful in discussing prognosis, advance care planning (e.g., living wills, healthcare power of attorney), and managing complex care needs and daily care routines.

- Online resources from patient advocacy groups (e.g., CurePSP, Brain Support Network, national dementia associations) can provide valuable information, support, and connection for families and caregivers dealing with corticobasal degeneration.

- Fall prevention is crucial. Patients with movement disorders and a history of falls (e.g., 2 or more falls in the past year, or any fall causing injury) require comprehensive assessment. This includes medication review, physical therapy for balance and strength training, home safety evaluation and modification, appropriate assistive device use, and patient/caregiver education on fall prevention strategies.

Reference List

- Boeve BF, Lang AE, Litvan I. Corticobasal degeneration and its relationship to progressive supranuclear palsy and frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 2003;54 Suppl 5:S15-9. doi: 10.1002/ana.10570.

- Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 2013;80(5):496-503. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f0fd1.

- Kouri N, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, Rademakers R, Dickson DW. Corticobasal degeneration: a pathologically distinct 4R tauopathy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(5):263-72. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.47.

- Stamelou M, Höglinger GU. A review of treatment options for progressive supranuclear palsy. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(7):629-36. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0351-y. [Note: While for PSP, some symptomatic approaches overlap or are considered for CBD].

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)