Otogenic intracranial complications

Otogenic Intracranial Complications: Overview

Otogenic intracranial complications refer to serious infections and inflammatory conditions developing within the cranial cavity that arise as a direct or indirect consequence of infections originating in the middle ear cleft (middle ear, mastoid air cells, Eustachian tube) [1]. These potentially life-threatening complications occur when the infectious process spreads beyond the confines of the temporal bone structures into adjacent areas, including the meninges (brain linings), brain parenchyma (tissue), and dural venous sinuses (large veins draining the brain). Both acute suppurative otitis media (AOM) and chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) can lead to these complications, although they are now considered significantly more common sequels of CSOM in the post-antibiotic era [2].

While AOM, particularly when complicated by acute coalescent mastoiditis, can certainly lead to intracranial issues (often via hematogenous spread or direct extension through thin, possibly dehiscent, bone, especially in children), CSOM poses a generally higher risk. This is primarily due to the nature of chronic inflammation, often associated with cholesteatoma (an expanding sac of keratinizing squamous epithelium), which characteristically causes progressive bone erosion and provides direct pathways for infection to spread intracranially. Complications are most frequent with chronic epitympanitis (attic cholesteatoma) but can also occur with chronic tubo-tympanic disease (pars tensa perforation) or non-cholesteatomatous CSOM with granulation tissue and osteitis [3].

Neuroimaging, particularly contrast-enhanced Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) including venography sequences, is essential for evaluating suspected intracranial complications arising from otitis media, allowing clear visualization of meningitis, abscesses (epidural, subdural, intracerebral), and venous sinus thrombosis.

The primary pathways for infectious spread from the ear into the cranial cavity include [4]:

- Direct Extension (Contiguous Spread): This remains the most frequent route, particularly in CSOM. Chronic inflammation, granulation tissue, cholesteatoma enzymes, and pressure effects erode the thin bony partitions separating the middle ear/mastoid from the middle cranial fossa (via the tegmen tympani/mastoidi) or the posterior cranial fossa (via the posterior fossa dural plate overlying the sigmoid sinus or cerebellum). Infection then directly contacts and inflames the dura mater, potentially progressing inwards.

- Hematogenous Dissemination (Bloodborne): Bacteria enter the bloodstream from the infected ear/mastoid focus (bacteremia) and travel to seed intracranial sites like the meninges or brain parenchyma. This can occur via:

- Venous Thrombophlebitis: This is a crucial mechanism. Infection causes inflammation and septic clotting within small diploic or emissary veins draining the temporal bone, allowing retrograde spread into the major dural venous sinuses (most commonly the adjacent sigmoid sinus, but also potentially the lateral, superior petrosal, or cavernous sinuses) or seeding the circulation. Septic emboli can also arise from these thrombosed veins/sinuses.

- Arterial Spread: Considered less common, involves bacteria traveling via small arteries supplying the temporal bone or meninges.

- Labyrinthine Route: Infection spreads medially through the inner ear structures (oval window, round window, or direct erosion) causing suppurative labyrinthitis, and then proceeds into the subarachnoid space via pre-formed pathways like the cochlear aqueduct, vestibular aqueduct, or the internal auditory canal (following the vestibulocochlear nerve). This route is thought to be significant in meningitis complicating AOM.

- Preformed Pathways: Congenital bony defects (e.g., patent petrosquamosal suture), skull fractures involving the temporal bone, or pathways created by previous ear surgery can serve as conduits for infection spread.

The most common bacterial species implicated in otogenic intracranial complications reflect the flora of complicated ear infections and include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae (less common Hib, more non-typeable), Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep), Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA), various anaerobic bacteria (like Bacteroides fragilis group, Peptostreptococcus spp., Fusobacterium spp.), and Gram-negative rods like Proteus mirabilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (especially common in chronic infections and cholesteatoma) [5]. Often, infections are polymicrobial, particularly those arising from CSOM.

The major categories of otogenic intracranial complications include [2]:

- Meningitis: Inflammation of the leptomeninges (pia and arachnoid mater). The most common otogenic intracranial complication overall.

- Epidural Abscess (Extradural Abscess): Collection of pus between the inner table of the skull and the dura mater, usually adjacent to the mastoid. Often asymptomatic or causes localized pain/headache.

- Subdural Empyema (Subdural Abscess): Collection of pus in the potential space between the dura and arachnoid mater. Spreads easily over brain surface; neurosurgical emergency. Less common than epidural or brain abscess from otogenic source compared to rhinogenic source.

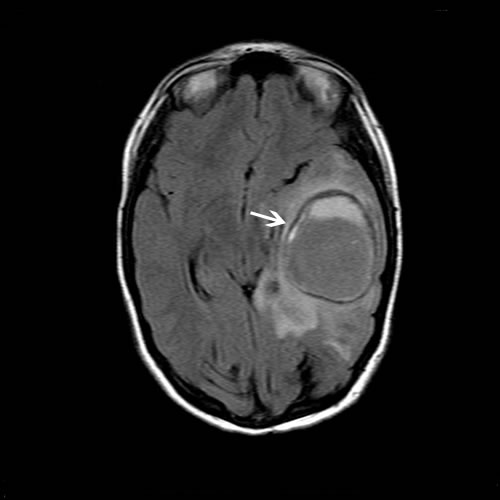

- Brain Abscess: Localized collection of pus within the brain parenchyma itself. Due to proximity, typically occurs in the temporal lobe (via tegmen erosion) or cerebellum (via posterior fossa plate/sinus spread). Second most common complication after meningitis.

- Dural Venous Sinus Thrombosis (Septic Thrombophlebitis): Inflammation and clotting within the dural venous sinuses. The sigmoid sinus is most commonly affected due to its direct adjacency to the mastoid air cells. Can extend to involve the transverse sinus, superior petrosal sinus, jugular bulb/vein, or even cavernous sinus. Can lead to increased intracranial pressure, venous infarction, sepsis, and propagation of clot.

- Otitic Hydrocephalus (now preferably termed Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension [IIH] associated with Otitic Disease): Syndrome of increased intracranial pressure (headache, papilledema, +/- CN VI palsy) with normal or small ventricles on imaging and normal CSF composition, occurring in the context of otitis media/mastoiditis, often associated with documented or presumed lateral sinus thrombosis impairing CSF absorption [6, 7].

- Arachnoiditis: Chronic inflammation and scarring of the arachnoid mater, sometimes occurring as a late sequela of previous otogenic meningitis or other intracranial inflammation.

It is crucial to recognize that these complications frequently occur in combination (e.g., meningitis with sigmoid sinus thrombosis and an epidural abscess). Therefore, comprehensive evaluation for all potential complications is necessary when one is suspected.

Diagnosis of Otogenic Intracranial Complications

Diagnosing otogenic intracranial complications requires a high index of clinical suspicion in any patient presenting with acute or chronic ear disease who develops headache, fever, altered mental status, seizures, focal neurological deficits, or persistent ear symptoms despite initial treatment. Prompt diagnosis relies heavily on advanced neuroimaging, supplemented by clinical assessment, laboratory tests, and potentially CSF analysis.

Differential Diagnosis of Neurological Symptoms in the Setting of Otitis Media / Mastoiditis

| Condition / Complication | Key Clinical Features | Primary Diagnostic Tool / Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Otogenic Meningitis | Acute onset headache, fever, neck stiffness, altered mental status. Signs of current/recent otitis/mastoiditis usually present. | Lumbar Puncture (LP) (if safe after imaging): CSF shows bacterial pattern (High WBC-Neutrophils, High Protein, Low Glucose). Brain MRI: May show leptomeningeal enhancement. CT Temporal Bone: Confirms otitis/mastoiditis source. |

| Epidural Abscess | Often subtle. Persistent localized headache (temporal/postauricular), fever (variable), mastoid tenderness. Neurological signs usually absent unless very large or complicated. Often identified during mastoidectomy. | Contrast-Enhanced MRI Brain (preferred) or CT Brain: Shows lenticular collection between inner skull table & dura, adjacent to temporal bone. Enhancement of adjacent dura is key. CT Temporal Bone: Shows mastoiditis +/- bone erosion. |

| Subdural Empyema | Neurosurgical Emergency! Rapid decline. High fever, severe headache, meningismus, prominent focal deficits (hemiparesis), seizures common. Altered mental status. Less common from otogenic vs rhinogenic source. | Contrast-Enhanced MRI Brain with DWI: Shows crescentic/layering subdural collection. Pus shows restricted diffusion (DWI bright, ADC dark). Enhancement of bounding membranes. LP contraindicated. CT Temporal Bone shows source. |

| Brain Abscess (Temporal Lobe / Cerebellum) | Often subacute onset (days/weeks). Headache, focal deficits (temporal: aphasia, quadrantanopia, seizures; cerebellar: ataxia, dysmetria, nystagmus), +/- fever (~50%). Signs of increased ICP later. | Contrast-Enhanced MRI Brain with DWI: Shows ring-enhancing lesion within brain parenchyma (temporal lobe or cerebellum common). Central cavity shows restricted diffusion (DWI bright, ADC dark). Surrounding edema. LP contraindicated if significant mass effect. |

| Sigmoid/Lateral Sinus Thrombosis (Septic) | Headache (often postauricular/occipital), fever ("spiking" pattern - Hectic fever / Sepsis), ear pain/discharge, mastoid tenderness/edema ('Griesinger's sign'). Signs of increased ICP (papilledema, CN VI palsy - 'Gradenigo's syndrome' if petrous apex involved). +/- Focal signs, seizures if venous infarct/extension. | MR Venography (MRV) or CT Venography (CTV) is diagnostic: Confirms lack of flow / filling defect (thrombus) in the sigmoid/transverse sinus. Contrast MRI Brain may show thrombus signal, intense dural enhancement near sinus ("delta sign" in SSS, but applies here too), adjacent mastoiditis/epidural inflammation, venous infarcts. CT Temporal Bone shows mastoiditis. Blood cultures may be positive. |

| Otitic Hydrocephalus (Secondary IIH) | Symptoms solely of increased ICP (headache, papilledema, visual changes, +/- CN VI palsy) occurring during or after an episode of otitis media/mastoiditis. No focal neurological signs (other than CN VI palsy), normal sensorium. Often associated with documented or presumed lateral sinus thrombosis. | MRI/MRV Brain: Normal or small/slit-like ventricles, empty sella possible. Crucially excludes mass lesion or obstructive hydrocephalus. Confirms associated lateral sinus thrombosis (present in most cases). LP (therapeutic/diagnostic): Elevated opening pressure, but normal CSF composition (cells, protein, glucose). |

| Labyrinthitis (Suppurative) | Acute onset severe vertigo, sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, nausea/vomiting, often associated with AOM or CSOM. Fever may be present. Neck stiffness usually absent unless progressing to meningitis. | Clinical diagnosis aided by audiometry (confirms SNHL) and vestibular testing. Contrast MRI Brain: May show enhancement of inner ear structures (labyrinth). CSF usually normal unless concomitant meningitis. |

| Petrous Apicitis / Gradenigo's Syndrome | Infection/inflammation of petrous apex air cells (medial part of temporal bone). Classic Gradenigo's triad: 1) Otorrhea (from underlying otitis), 2) Retro-orbital/facial pain (V1/V2 distribution due to trigeminal ganglion irritation), and 3) CN VI palsy (abducens nerve palsy causing diplopia due to involvement near Dorello's canal). | High-Resolution CT Temporal Bone (best for bone detail) +/- MRI Brain/Skull Base: Shows opacification +/- erosion/osteomyelitis of petrous apex, enhancement of adjacent structures. Requires specific focus on petrous apex imaging. |

| Non-Otogenic Causes (e.g., Stroke, Tumor, Viral Meningitis) | May present with similar neurological symptoms but lack clear link to current/recent ear infection. Clinical context, specific neurological signs, and imaging patterns differ. | Depends on condition. MRI Brain often key. LP essential for differentiating meningitis types. Temporal bone CT usually normal or shows unrelated findings. |

Note: Patients may present with more than one complication simultaneously.

Key diagnostic steps involve:

- Clinical Evaluation: Thorough history regarding ear symptoms (acute vs. chronic), associated neurological symptoms (headache type/location, fever pattern, seizures, focal deficits, vision changes, altered consciousness), and prior treatments. Complete neurological and otological examination, including otoscopy/microscopy, tuning fork tests, cranial nerve assessment, funduscopy, and meningeal sign testing.

- Laboratory Tests: CBC with differential, inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP), blood cultures (especially if febrile).

- Neuroimaging: Essential for confirming diagnosis, identifying the specific complication(s), delineating extent, and guiding management.

- Contrast-Enhanced MRI Brain with MRV: Generally the most comprehensive single study. Excellent for meningitis, brain abscess, subdural empyema (esp. DWI), venous sinus thrombosis (MRV), labyrinthitis, and associated edema/infarction [2, 8].

- High-Resolution CT Temporal Bones: Best for assessing bony anatomy, extent of mastoid/middle ear disease, bone erosion (tegmen, sigmoid plate), cholesteatoma, and petrous apex involvement [9]. Often performed in conjunction with MRI/CT brain.

- Contrast-Enhanced CT Brain with CTV: Alternative if MRI contraindicated or unavailable. Good for epidural abscess, bone erosion, hydrocephalus, and detecting sinus thrombosis (CTV). Less sensitive for subdural empyema, early abscess/cerebritis, and non-hemorrhagic infarcts compared to MRI.

- Lumbar Puncture (LP) for CSF Analysis: Indicated primarily when meningitis is suspected AND neuroimaging (usually CT first) has excluded significant mass effect (abscess, large empyema, severe edema) that poses a herniation risk. Confirms meningitis and helps identify pathogen. Generally contraindicated in the presence of brain abscess or subdural empyema with mass effect.

- Audiometry: Useful if hearing loss or labyrinthitis is suspected.

Recognizing specific clinical syndromes (like Gradenigo's triad for petrous apicitis, or signs of raised ICP with papilledema suggesting sinus thrombosis or otitic hydrocephalus) can help guide investigations. The combination of clinical findings, targeted imaging of both the brain and temporal bone, and CSF analysis (when safe) usually allows for accurate diagnosis of the specific otogenic intracranial complication(s).

Otogenic Intracranial Complications: Prevention and Treatment

Prevention: The most effective strategy for preventing these serious complications is the prompt, adequate, and consistent medical and/or surgical treatment of both acute and chronic otitis media and mastoiditis. Early diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic therapy for AOM, particularly in high-risk individuals or those with persistent symptoms, is crucial. For CSOM, especially cases involving cholesteatoma, significant granulation tissue, polyps, or radiographic evidence of bone erosion, timely surgical intervention (middle ear and mastoid surgery, e.g., tympanomastoidectomy) is often necessary to eradicate the chronic disease focus and prevent intracranial extension [10]. Patients with chronic ear disease require regular otologic follow-up to monitor for disease progression or complications.

Treatment: Management of established otogenic intracranial complications is a medical and surgical emergency requiring urgent hospitalization and a coordinated multidisciplinary approach, typically involving Otolaryngology (ENT), Neurosurgery, Infectious Disease specialists, Neurology, and Radiology specialists [2, 4].

- Medical Management:

- High-Dose Intravenous Antibiotics: Immediate initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics with good CNS and bone penetration is essential upon suspicion. Empirical choices must cover likely otogenic pathogens (aerobes and anaerobes). Combination therapy is standard practice initially, often including:

- Vancomycin (for MRSA, resistant pneumococci)

- A third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin (e.g., Ceftriaxone, Cefotaxime, or Cefepime)

- Metronidazole (for excellent anaerobic coverage)

- Adjunctive Dexamethasone: May be considered for bacterial meningitis (given with/before first antibiotic dose) primarily to reduce hearing loss risk, especially if pneumococcal cause suspected [12]. Role in other complications is less clear and often avoided unless severe edema causing mass effect.

- Supportive Care: Critical care management may be needed. Includes management of fever, pain, hydration, electrolytes, nutrition, and prevention of complications (e.g., DVT prophylaxis, stress ulcer prophylaxis).

- Management of Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP): Urgent measures like head elevation, osmotic therapy, potentially sedation/ventilation, and neurosurgical consultation for possible ICP monitoring or CSF diversion (EVD).

- Seizure Management: Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) administered promptly if seizures occur. Prophylactic AEDs often considered, especially with subdural empyema or brain abscess.

- Anticoagulation: Generally recommended for septic dural venous sinus thrombosis once hemorrhage risk is acceptable, to prevent clot propagation [13].

- High-Dose Intravenous Antibiotics: Immediate initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics with good CNS and bone penetration is essential upon suspicion. Empirical choices must cover likely otogenic pathogens (aerobes and anaerobes). Combination therapy is standard practice initially, often including:

- Surgical Management: This typically involves two key components: source control (addressing the ear infection) and drainage of intracranial collections.

- Source Control (Ear Surgery): Eradication of the primary infection in the middle ear and mastoid by an otolaryngologist is almost always required, especially for complications arising from CSOM or coalescent mastoiditis. This involves performing the appropriate mastoidectomy (e.g., complete, radical, or modified radical).

- Drainage/Management of Intracranial Complications (Neurosurgery +/- ENT):

- Epidural Abscess: Often drained during the mastoidectomy. Larger abscesses may require separate neurosurgical drainage.

- Subdural Empyema: Requires urgent neurosurgical drainage, usually via craniotomy.

- Brain Abscess: Requires neurosurgical intervention, typically stereotactic aspiration or craniotomy with excision/drainage.

- Sigmoid Sinus Thrombosis: Primarily medical management (antibiotics, anticoagulation). Surgery rarely indicated unless large adjacent epidural abscess requires decompression.

Despite significant advances, otogenic intracranial complications remain serious conditions associated with potential mortality (ranging from <5% for uncomplicated meningitis to 10-20% or higher for subdural empyema or complicated brain abscess/sinus thrombosis) and significant long-term neurological sequelae (hearing loss, seizures, focal deficits). Prompt diagnosis, aggressive antibiotic therapy, and timely surgical intervention are critical.

![]() Attention! Any patient with ear problems who develops severe headache, fever, neck stiffness, altered consciousness, seizures, or focal weakness requires immediate medical evaluation in an emergency setting to rule out potentially life-threatening otogenic intracranial complications.

Attention! Any patient with ear problems who develops severe headache, fever, neck stiffness, altered consciousness, seizures, or focal weakness requires immediate medical evaluation in an emergency setting to rule out potentially life-threatening otogenic intracranial complications.

References

- Osman M, et al. Otogenic intracranial complications: A review. J Otol. 2011;6(2):69-75. doi: 10.1016/j.joto.2011.08.005

- Manolidis S, et al. Complications of otitis media. In: Snow JB, Wackym PA, eds. Ballenger's Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 17th ed. BC Decker; 2009.

- Pennybacker J. Discussion on intracranial complications of otogenic origin. Proc R Soc Med. 1961;54:309-20.

- Kangsanant S, et al. Intracranial complications of suppurative otitis media: 13 years' experience. Am J Otol. 1995;16(6):707-12.

- Brook I. Intracranial complications of infections of the head and neck. J Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):329-71. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00011-09

- Symonds CP. Otitic hydrocephalus. Brain. 1931;54(1):55-71. doi: 10.1093/brain/54.1.55

- Johnston I, et al. The definition and clinical characteristics of otitic hydrocephalus. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 1B):419-32. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.1.419

- Lo WWM, et al. Intracranial complications of sinus and otic infections. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2004;14(2):197-218. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2004.03.005

- Juliano AF, et al. Imaging review of the temporal bone: part I. Anatomy and inflammatory conditions. Radiology. 2013;269(1):17-33. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13120733

- Roland PS, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Cholesteatoma (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(1_suppl):S1-S23. doi: 10.1177/0194599815617207

- Chapter 91: Brain Abscess and Other Parameningeal Infections. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- van de Beek D, et al. Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004405. Updated 2015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004405.pub5

- Saposnik G, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council and the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(4):1158-92. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e31820a8364

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)