Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism

Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism Overview

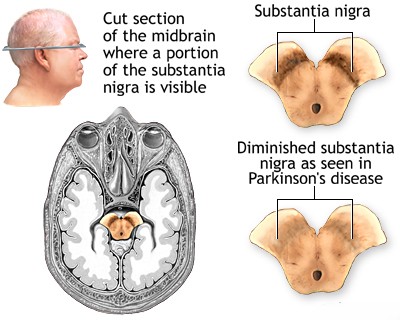

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disorder primarily characterized by motor symptoms resulting from the substantial loss of dopamine-producing (dopaminergic) neurons in a specific midbrain region called the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) [1]. These SNc neurons normally project via the nigrostriatal pathway to the basal ganglia (specifically the striatum: caudate nucleus and putamen), structures deep within the cerebral hemispheres crucial for initiating and controlling voluntary movement, motor learning, habit formation, and other functions.

Dopamine acts as a key neurotransmitter modulating activity within the basal ganglia circuits (direct and indirect pathways). The progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in PD leads to a significant dopamine deficiency in the striatum, disrupting the delicate balance of these circuits [2].

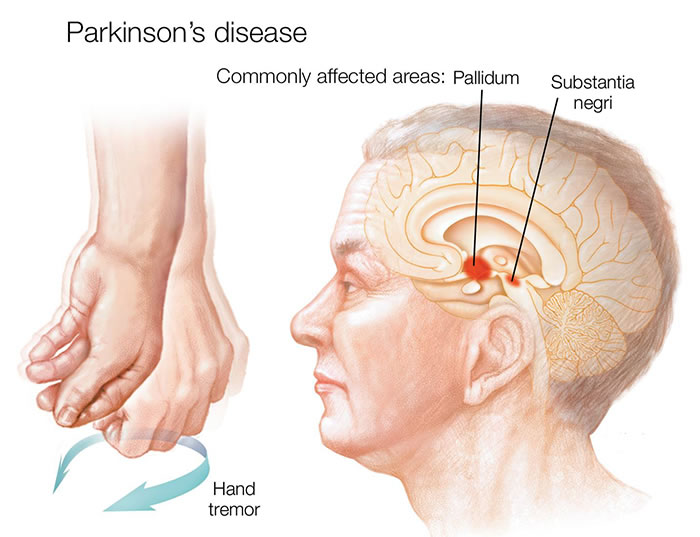

This dopamine deficit disrupts the normal functioning of the basal ganglia motor loops, leading to the cardinal motor symptoms known collectively as parkinsonism. According to current clinical diagnostic criteria (e.g., MDS Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson's Disease), parkinsonism is defined by the presence of bradykinesia in combination with at least one of the other two cardinal signs: rigidity or resting tremor [3].

- Bradykinesia: Slowness and poverty of movement. This is considered the most characteristic feature of parkinsonism and involves difficulty initiating movement (akinesia), reduced speed of movement, and progressive reduction in amplitude and speed of repetitive actions (sequence effect).

- Muscle Rigidity: Increased resistance to passive movement throughout the range of motion, felt by the examiner. Can be smooth ("lead pipe") or ratchet-like ("cogwheel" rigidity, often superimposed tremor).

- Resting Tremor: Involuntary shaking, typically starting unilaterally in a limb (often hand or foot, sometimes jaw/lip), most prominent when the limb is fully supported and at rest, often temporarily suppressed by voluntary movement. Frequency is usually 4-6 Hz. A characteristic "pill-rolling" appearance in the hand is common.

- Postural Instability: Impaired balance reflexes leading to unsteadiness and falls. While part of parkinsonism, it typically occurs later in the course of idiopathic Parkinson's disease and its early prominence is a "red flag" suggesting atypical parkinsonism [3].

Other associated motor features supporting the diagnosis of PD can include micrographia (small, cramped handwriting), hypophonia (soft, monotonous speech), masked facies (reduced facial expression, "poker face"), decreased blink rate, freezing of gait, and a shuffling gait with reduced arm swing.

It is crucial to distinguish Parkinson's disease (PD), the specific neurodegenerative disorder characterized pathologically by SNc neuron loss and the presence of intraneuronal protein aggregates called Lewy bodies (containing alpha-synuclein), from the broader clinical syndrome of parkinsonism. Parkinsonism can be caused by conditions other than PD, including certain medications (drug-induced parkinsonism), other neurodegenerative disorders (atypical parkinsonism, such as Multiple System Atrophy [MSA], Progressive Supranuclear Palsy [PSP], Corticobasal Degeneration [CBD]), vascular parkinsonism (due to strokes), normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), infections (post-encephalitic parkinsonism - rare now), toxins, and trauma [4].

Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Parkinson's disease (PD) remains primarily clinical, based on a careful interpretation of the patient's medical history, reported symptoms, and findings on a detailed neurological examination performed by an experienced clinician, ideally a neurologist specializing in movement disorders. Currently, there is no single definitive biological marker or diagnostic test (like a blood test or standard brain scan) that can unequivocally confirm idiopathic Parkinson's disease during life, although research is ongoing [5]. Definitive diagnosis still requires post-mortem neuropathological confirmation of SNc neuron loss and Lewy body pathology.

Clinical diagnostic criteria, such as those established by the UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank or the more recent Movement Disorder Society (MDS) Clinical Diagnostic Criteria, provide a standardized framework [3]. Key diagnostic steps involve:

- Establishment of Parkinsonism: This is the essential first step. Parkinsonism is defined clinically by the presence of bradykinesia (slowness of initiation of voluntary movement with progressive reduction in speed and amplitude during repetitive actions) in combination with at least one of the following:

- Muscle rigidity (lead-pipe or cogwheel type).

- Resting tremor (typically 4-6 Hz).

- Assessment for Parkinson's Disease Criteria: Once parkinsonism is established, the diagnosis leans towards PD if:

- There are no absolute exclusion criteria present (see below).

- There are at least two supportive criteria present (positive features commonly seen in PD).

- There are no "red flags" present (features that raise suspicion for an alternative diagnosis).

- Clear and dramatic beneficial response (improvement >30%) to dopaminergic therapy (levodopa).

- Presence of levodopa-induced dyskinesias.

- Resting tremor of a limb observed clinically.

- Presence of olfactory dysfunction (loss or reduced sense of smell).

- Cardiac sympathetic denervation on MIBG scintigraphy (less commonly used clinically).

- Evaluation for Exclusion Criteria and Red Flags: Features that argue strongly against PD or suggest an alternative diagnosis (atypical parkinsonism or secondary parkinsonism).

Absolute Exclusion Criteria (Rule out PD if present):

- Unequivocal cerebellar abnormalities (ataxia, nystagmus).

- Downward vertical supranuclear gaze palsy, or selective slowing of downward saccades.

- Diagnosis of probable behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia or primary progressive aphasia within the first 5 years.

- Parkinsonian features restricted to the lower limbs for more than 3 years.

- Treatment with a dopamine receptor blocker or dopamine-depleting agent in a dose and time-course consistent with drug-induced parkinsonism.

- Absence of observable response to high-dose levodopa despite at least moderate severity of disease.

- Unequivocal cortical sensory loss, clear limb ideomotor apraxia, or progressive aphasia.

- Normal functional neuroimaging of the presynaptic dopaminergic system (e.g., normal DAT scan).

- Rapid progression of gait impairment requiring regular wheelchair use within 5 years of onset.

- Complete absence of progression of motor symptoms or signs over 5 or more years unless stability is treatment-related.

- Early bulbar dysfunction (severe dysarthria or dysphagia within first 5 years).

- Early inspiratory respiratory dysfunction (daytime or nocturnal inspiratory stridor).

- Severe autonomic failure within first 5 years (e.g., severe orthostatic hypotension, severe urinary retention/incontinence not explained otherwise).

- Recurrent falls (>1/year) due to impaired balance within 3 years of onset.

- Disproportionate anterocollis or contractures within first 10 years.

- Absence of any common non-motor features despite 5 years disease duration (sleep dysfunction, autonomic dysfunction, hyposmia, psychiatric).

- Otherwise unexplained pyramidal tract signs.

- Bilateral symmetric parkinsonism onset without clear asymmetry persisting.

Differential Diagnosis of Parkinsonism

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features (Compared to typical PD) | Typical Levodopa Response / Ancillary Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | Often asymmetric onset, prominent resting tremor common, good levodopa response initially, olfactory loss common, slower progression early on. Development of motor fluctuations/dyskinesias later. Non-motor symptoms (constipation, RBD, depression) common. | Excellent/good initial levodopa response is supportive. MRI brain usually normal. DAT scan abnormal (reduced striatal uptake, asymmetric initially). |

| Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) | Combination of parkinsonism (MSA-P) OR cerebellar signs (MSA-C) PLUS early, prominent autonomic failure (orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence/retention, erectile dysfunction). +/- Pyramidal signs, stridor, anterocollis, emotional lability ("pathological laughter/crying"). Faster progression. | Often poor or unsustained levodopa response. MRI may show specific signs: putaminal atrophy/hypointensity/hyperintense rim ("slit sign" - MSA-P) or cerebellar/pontine atrophy ("hot cross bun" sign - MSA-C). DAT scan abnormal. Autonomic function tests abnormal. |

| Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) | Early postural instability and falls (often backwards, "rocket sign"). Vertical supranuclear gaze palsy (especially downward gaze limitation). Symmetric axial rigidity > appendicular, bradykinesia. Frontal lobe signs (cognitive/behavioral changes, apathy, pseudobulbar affect). Dysphagia, dysarthria ("growling speech"). "Surprised" facial expression. | Poor levodopa response usually. MRI may show characteristic midbrain atrophy ("hummingbird" or "penguin" sign on sagittal), superior cerebellar peduncle atrophy. DAT scan abnormal. |

| Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD) / Corticobasal Syndrome (CBS) | Markedly asymmetric parkinsonism (rigidity, bradykinesia, often dystonia). Associated cortical signs in affected limb: apraxia (limb ideomotor), alien limb phenomenon (limb feels foreign/moves involuntarily), cortical sensory loss (astereognosis, agraphesthesia), myoclonus (reflex or spontaneous). Cognitive/behavioral changes common. | Poor levodopa response usually. MRI may show asymmetric cortical atrophy (perirolandic/frontoparietal, contralateral to affected limb). DAT scan abnormal, often asymmetric. FDG-PET may show asymmetric hypometabolism. |

| Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) | Parkinsonism develops within one year of dementia onset (or concurrently). Core features: Fluctuating cognition/alertness, recurrent complex visual hallucinations (often well-formed people/animals), spontaneous parkinsonism, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). Marked sensitivity to antipsychotic medications. | Variable levodopa response (may improve motor, worsen psychosis). MRI usually normal or shows non-specific atrophy. DAT scan abnormal. Polysomnography confirms RBD. |

| Drug-Induced Parkinsonism (DIP) | History of exposure to dopamine receptor blocking agents (typical/atypical antipsychotics - risperidone, haloperidol; antiemetics - metoclopramide, prochlorperazine) or dopamine depleters (tetrabenazine). Often symmetric parkinsonism. Tremor may be less prominent or postural. May have associated tardive dyskinesia or akathisia. | No levodopa response. Symptoms improve/resolve after stopping offending drug (may take weeks to months). DAT scan typically normal (distinguishes from PD/atypical syndromes). |

| Vascular Parkinsonism (VP) | Often lower body predominant parkinsonism ("lower half" or "vascular pseudoparkinsonism") with gait disturbance (freezing, short shuffling steps, wide base, "gait apraxia") out of proportion to upper limb signs. History of stroke(s) or prominent vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes). +/- Pyramidal signs, cognitive impairment (vascular dementia), pseudobulbar affect. Tremor less common/prominent. | Poor levodopa response typically. MRI Brain shows significant cerebrovascular disease (multiple lacunar infarcts, extensive white matter hyperintensities, strategic infarcts in basal ganglia/thalamus/subcortical regions). DAT scan result is variable (can be normal or abnormal depending on location of vascular lesions). |

| Essential Tremor (ET) | Primarily a postural and action tremor (kinetic tremor), affecting hands/arms (often bilateral but can be asymmetric), head ("yes-yes" or "no-no"), or voice. Absence of significant bradykinesia, rigidity, or resting tremor component. Family history common (~50%). Alcohol often provides temporary improvement. | No levodopa response. Neurological examination otherwise typically normal (no bradykinesia/rigidity). DAT scan normal. |

| Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) | Classic triad: Gait disturbance (magnetic, wide-based, shuffling, difficulty initiating), cognitive impairment (frontal-subcortical type), urinary incontinence. Parkinsonism features (esp. lower body bradykinesia/rigidity) can occur but tremor less common. | Variable or no levodopa response. MRI Brain shows ventriculomegaly out of proportion to sulcal atrophy (Evans' index >0.3), possible aqueductal flow void, periventricular white matter changes. Large volume lumbar puncture (CSF tap test) may result in temporary gait improvement. May require CSF shunt surgery. |

While the clinical diagnosis by an experienced neurologist is highly accurate (often >90% when using established criteria), ancillary tests may aid in specific situations or help differentiate from mimics:

- Brain MRI: Primarily used to exclude structural mimics (tumors, strokes, hydrocephalus). Standard MRI sequences are usually normal or show non-specific age-related changes in idiopathic PD. Specific sequences or findings may suggest atypical parkinsonism (e.g., atrophy patterns in MSA/PSP, extensive vascular disease in VP).

- Dopamine Transporter Scan (DAT Scan, e.g., DaTscan™ using 123I-ioflupane SPECT): Images the integrity of presynaptic dopamine transporters in the striatum. Reduced uptake is characteristic of neurodegenerative parkinsonism (PD, MSA, PSP, CBD, DLB) where the nigrostriatal pathway is damaged. A normal DAT scan strongly argues against these conditions and supports diagnoses like essential tremor, drug-induced parkinsonism, or psychogenic parkinsonism [6]. Note: It cannot distinguish PD from the atypical syndromes.

- Response to Levodopa Trial: A robust, sustained improvement in motor symptoms following an adequate trial of levodopa (e.g., up to 1000mg/day for several weeks/months) is highly supportive of PD, although some atypical syndromes may show mild or transient response. Lack of clear benefit makes PD less likely [7].

- Olfactory Testing: Formal testing can reveal hyposmia or anosmia, which is very common (>90%) in PD, often preceding motor symptoms. While not specific (also seen in other conditions), normal sense of smell makes PD less probable [8].

- Other: Autonomic function testing (for MSA), polysomnography (for RBD in synucleinopathies like PD/DLB/MSA), MIBG cardiac scintigraphy (shows cardiac sympathetic denervation in PD/DLB, usually normal in MSA/PSP), neuropsychological testing (for cognitive patterns), genetic testing (if familial/young onset suspected) may be used in specific contexts.

While standard Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is often unremarkable in early Parkinson's disease, it is frequently performed during the diagnostic workup primarily to exclude other structural causes of parkinsonism, such as stroke, tumors, hydrocephalus, or specific atrophy patterns suggestive of atypical parkinsonian syndromes. Functional imaging like DAT scans assesses the dopamine system directly.

Differentiating PD from other causes of parkinsonism ("Parkinson-plus" syndromes or secondary parkinsonism) is crucial because prognosis and response to treatment differ significantly. Drug-induced parkinsonism often improves or resolves upon withdrawal of the offending medication. Atypical parkinsonian syndromes (MSA, PSP, CBD) generally have a faster rate of progression, develop additional disabling features earlier (autonomic failure, falls, gaze palsy, cortical signs, dementia), and respond poorly or transiently to levodopa compared to typical PD.

Cognitive impairment and dementia are common non-motor features of PD, but typically occur later in the disease course (often many years after motor onset) – this is termed Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD). If significant dementia occurs very early, specifically within the first year of motor symptom onset, the diagnosis is usually considered Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) according to current consensus criteria [9]. The prevalence of dementia increases significantly with age and disease duration in PD, potentially affecting up to 80% of patients in the very advanced stages (>15-20 years duration) [10].

Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism Treatment

While there is currently no cure that stops or reverses the underlying neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease, a range of effective treatments are available to manage symptoms, significantly improve quality of life, and help maintain function and independence for many years [11]. Treatment is highly individualized, tailored to the specific symptoms, disease stage, degree of functional impairment, age, lifestyle, comorbidities, and patient preferences. Management typically involves a combination of pharmacological therapies, essential non-pharmacological approaches, and sometimes advanced therapies like deep brain stimulation.

Pharmacological Treatment: The primary goal is to alleviate motor symptoms by enhancing dopaminergic function.

- Levodopa (L-DOPA, typically combined with a peripheral decarboxylase inhibitor like carbidopa or benserazide): Remains the most effective symptomatic treatment for the motor features of PD, particularly bradykinesia and rigidity [12]. Dosage needs careful titration ("start low, go slow") to find the lowest effective dose that provides benefit while minimizing acute side effects (nausea, orthostatic hypotension). Long-term use is often associated with the development of motor complications:

- Wearing-off: Predictable return of symptoms before the next dose is due.

- Dyskinesias: Involuntary, often choreiform or dystonic movements, typically occurring at peak levodopa levels ("peak-dose dyskinesia").

- "On-Off" fluctuations: Unpredictable shifts between periods of good mobility ("on" time) and poor mobility/return of parkinsonian symptoms ("off" time).

- Dopamine Agonists (DAs) (e.g., pramipexole, ropinirole - oral; rotigotine - transdermal patch; apomorphine - subcutaneous injection/infusion for rescue/advanced therapy): Directly stimulate dopamine receptors. Can be used as initial monotherapy, especially in younger patients (< 60-70) to potentially delay the need for levodopa and reduce risk of early motor complications, or used as adjunct therapy to levodopa in later stages to reduce "off" time and allow lower levodopa doses [13]. DAs generally have less potent motor benefit than levodopa but longer duration of action. They carry a higher risk of certain side effects, including excessive daytime somnolence, sudden sleep attacks, hallucinations (especially in elderly/cognitively impaired), peripheral edema, and impulse control disorders (ICDs - e.g., pathological gambling, compulsive shopping, hypersexuality, binge eating) which require careful monitoring.

- MAO-B Inhibitors (Monoamine Oxidase B Inhibitors) (e.g., selegiline, rasagiline, safinamide): Inhibit the enzyme MAO-B, which breaks down dopamine in the brain, thus increasing dopamine availability. Provide mild symptomatic benefit as monotherapy in early disease or can be used adjunctively with levodopa to reduce "off" time [14]. Safinamide also has anti-glutamatergic properties that may help dyskinesia.

- COMT Inhibitors (Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Inhibitors) (e.g., entacapone, opicapone): Block the peripheral breakdown of levodopa by COMT, thereby increasing the amount of levodopa reaching the brain and extending its duration of action. Used only as adjuncts to levodopa to manage "wearing-off" phenomena [15]. Tolcapone is another COMT inhibitor but requires liver function monitoring due to risk of hepatotoxicity.

- Amantadine: Mechanism is complex (weak NMDA antagonist, enhances dopamine release, anticholinergic effects). Provides mild benefit for bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor early on. Particularly useful later in the disease for treating levodopa-induced dyskinesias [16]. Side effects can include confusion, hallucinations, livedo reticularis, ankle edema.

- Anticholinergics (e.g., trihexyphenidyl, benztropine): Primarily block acetylcholine effects, mainly useful for reducing tremor, especially in younger patients (< 60-70) with tremor as the predominant symptom. Generally avoided in older adults or those with cognitive impairment due to significant risk of side effects like confusion, memory problems, hallucinations, dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision.

Non-Pharmacological Therapies: These are essential complements to medication for optimal management and quality of life.

- Physical Therapy / Exercise: Crucial at all stages. Improves gait, balance, flexibility, posture, coordination, and cardiovascular fitness. Reduces risk of falls. Specific programs addressing amplitude of movement (e.g., LSVT BIG®), balance training, resistance exercise, aerobic exercise (walking, cycling, swimming, dancing like tango), and Tai Chi have demonstrated benefits [17]. Regular, sustained exercise is key.

- Occupational Therapy: Helps patients adapt daily living activities (dressing, eating, writing) and modify their home environment to maintain safety and independence despite motor and non-motor symptoms.

- Speech Therapy: Addresses speech problems (hypophonia - soft voice, monotone, dysarthria) and swallowing difficulties (dysphagia). Specific intensive programs like LSVT LOUD® are effective for improving voice volume [18].

- Nutritional Support: Guidance on maintaining adequate nutrition and hydration, managing constipation (high fiber, fluids, exercise), and sometimes adjusting protein intake timing relative to levodopa doses (high protein meals can sometimes interfere with levodopa absorption).

- Psychological Support / Mental Health Care: Addressing common non-motor symptoms like depression, anxiety, apathy, psychosis (often medication-related), and sleep disorders is critical. Counseling, support groups, and appropriate psychotropic medications may be needed.

- Complementary Therapies: Some patients explore therapies like massage, osteopathy/manual therapy, acupuncture, yoga, or music therapy for symptomatic relief (e.g., pain, stiffness, stress), though high-quality evidence for efficacy specifically for PD motor symptoms is often limited. They should complement, not replace, conventional evidence-based treatments.

Advanced Therapies / Surgical Treatment: Considered for select patients with PD who experience disabling motor complications (fluctuations, dyskinesias) or medication-refractory tremor despite optimized oral/transdermal medical management.

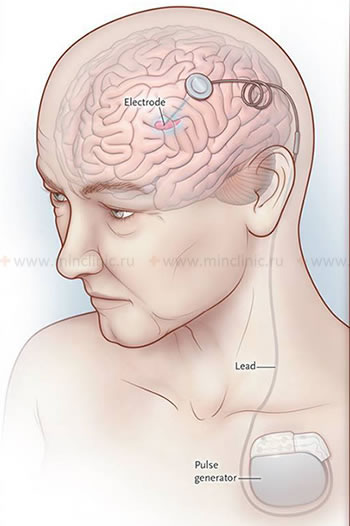

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): Currently the most common and effective surgical approach for advanced PD [19]. Involves stereotactic brain surgery to precisely implant thin electrodes into specific deep brain targets (most commonly the subthalamic nucleus - STN or the globus pallidus interna - GPi). These electrodes are connected via wires under the skin to an implanted neurostimulator (pulse generator, similar to a pacemaker, usually placed in the chest wall). The device delivers continuous high-frequency electrical pulses to modulate abnormal neuronal activity within the targeted basal ganglia circuit. DBS can significantly improve tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, motor fluctuations ("on-off" time), and levodopa-induced dyskinesias, often allowing for a reduction in medication dosages. It does not cure the disease or stop its progression and is generally less effective for non-motor symptoms or axial symptoms like balance problems and freezing of gait (though GPi DBS might be slightly better for gait/dyskinesia, STN for medication reduction). Careful patient selection and experienced multidisciplinary team are crucial for success.

- Lesioning Surgery (Ablative Procedures): Historically involved creating precise, irreversible lesions in targets like the thalamus (thalamotomy, primarily for tremor) or globus pallidus (pallidotomy, primarily for dyskinesia/rigidity). Largely replaced by the adjustability and reversibility of DBS, but still performed occasionally in specific situations or centers.

- Magnetic Resonance-guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS): A newer, incisionless ablative technique using highly focused ultrasound waves guided by real-time MRI thermometry to create precise thermal lesions in deep brain targets (e.g., the ventral intermediate nucleus [Vim] of the thalamus for tremor) without requiring craniotomy or electrode implantation. Currently FDA-approved primarily for medication-refractory essential tremor and tremor-dominant Parkinson's disease (unilateral thalamotomy) [20]. Research is ongoing for other targets (e.g., pallidotomy).

- Levodopa-Carbidopa Intestinal Gel (LCIG) Infusion: A device-aided therapy involving continuous infusion of a gel formulation of levodopa-carbidopa directly into the duodenum/jejunum via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube connected to a portable pump. Provides more continuous dopaminergic stimulation, effectively reducing "off" time and dyskinesias in advanced PD with severe motor fluctuations [21]. Requires managing the pump and PEG tube.

- Subcutaneous Apomorphine Infusion: Continuous subcutaneous infusion of the dopamine agonist apomorphine via a portable pump. Another option for advanced PD with refractory motor fluctuations, reducing "off" time [22]. Requires managing infusion sites for potential nodules.

Treatment of Parkinson's disease requires ongoing monitoring and periodic adjustments by a neurologist or movement disorder specialist as the disease progresses and the patient's needs evolve. Addressing non-motor symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, psychosis, constipation, fatigue, sleep disorders like REM sleep behavior disorder or insomnia, cognitive impairment/dementia) is also a critical part of comprehensive, patient-centered care, often requiring additional specific therapies.

![]() Attention! The diagnosis and management of Parkinson's disease and other parkinsonian syndromes are complex. Symptoms suggestive of parkinsonism warrant evaluation by a neurologist, preferably one specializing in movement disorders, for accurate diagnosis and individualized treatment planning. Self-diagnosis or altering medications without medical supervision can be dangerous.

Attention! The diagnosis and management of Parkinson's disease and other parkinsonian syndromes are complex. Symptoms suggestive of parkinsonism warrant evaluation by a neurologist, preferably one specializing in movement disorders, for accurate diagnosis and individualized treatment planning. Self-diagnosis or altering medications without medical supervision can be dangerous.

References

- Dickson DW. Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism: neuropathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Aug;2(8):a009258. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009258

- Obeso JA, et al. The basal ganglia and disorders of movement: pathophysiological mechanisms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(2):131-136. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.2.131

- Postuma RB, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2015 Oct;30(12):1591-601. doi: 10.1002/mds.26424

- Jankovic J. Parkinson's disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008 Apr;79(4):368-76. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045

- Armstrong MJ, Okun MS. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2020 Feb 11;323(6):548-560. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22360

- Kägi G, et al. The role of DAT-SPECT in movement disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(1):5-12. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.157370

- Merims D, Giladi N. Levodopa challenge test for the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(10):1469-74. doi: 10.1002/mds.22092

- Doty RL. Olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(6):329-39. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.80

- McKeith IG, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017 Jul 4;89(1):88-100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058

- Aarsland D, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of dementia in Parkinson disease: an 8-year prospective study. Arch Neurol. 2003 Mar;60(3):387-92. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.387

- Bloem BR, Okun MS, Lang AE. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2021 Jun 12;397(10291):2284-2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00218-X

- Fahn S, et al; Parkinson Study Group. Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 9;351(24):2498-508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033447

- Rascol O, et al. Ropinirole in the treatment of early Parkinson's disease: a 3-year study. Neurology. 1998;51(5):1460-7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1460

- Parkinson Study Group. A controlled trial of rasagiline in early Parkinson disease: the TEMPO study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(12):1937-43. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.12.1937

- Brooks DJ, et al; Laroscor Study Group. Opicapone for the management of levodopa-associated motor fluctuations in patients with Parkinson's disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(2):187-195. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4721

- Wolf E, et al. Amantadine for dyskinesia in Parkinson disease: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;74(21):1698-705. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e0f4e9

- Tomlinson CL, et al. Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention for Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD002817. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002817.pub4

- Ramig LO, et al. Intensive voice treatment (LSVT) for patients with Parkinson's disease: a 2 year follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(4):493-8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.4.493

- Deuschl G, et al; DBS study group. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 31;355(9):896-908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060281

- Bond AE, et al. Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor: 5-year follow-up. J Neurosurg. 2021 Nov 19:1-7. doi: 10.3171/2021.8.JNS211503

- Olanow CW, et al. Continuous intrajejunal infusion of levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel for patients with advanced Parkinson's disease: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, double-dummy study. Lancet Neurol. 2014 Feb;13(2):141-9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70293-X

- Katzenschlager R, et al; Apomorphine-PUMP study investigators group. Apomorphine subcutaneous infusion in patients with Parkinson's disease with persistent motor fluctuations (TOLEDO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Sep;17(9):749-759. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30239-4

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Central nervous system infection:

- Brain abscess (lobar, cerebellar)

- Eosinophilic granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Hennebert's symptom

- Epidural brain abscess

- Sinusitis-associated intracranial complications

- Otogenic intracranial complications

- Sinusitis-associated ophthalmic complications

- Bacterial otogenic meningitis

- Subdural brain abscess

- Sigmoid sinus suppurative thrombophlebitis

- Cerebral 3rd Ventricle Colloid Cyst

- Cerebral and spinal adhesive arachnoiditis

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (Limited Brain Atrophy)

- Encephalopathy

- Headache, migraine

- Traumatic brain injury (concussion, contusion, brain hemorrhage, axonal shearing lesions)

- Increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus

- Parkinson's disease

- Pituitary microadenoma, macroadenoma and nonfunctioning adenomas (NFPAs), hyperprolactinemia syndrome

- Spontaneous cranial cerebrospinal fluid leak (CSF liquorrhea)