Retina and optic disc, visual impairment when they are affected

- Understanding the Retina and Optic Disc

- Common Pathologies of the Retina and Optic Disc Leading to Visual Impairment

- Diagnosis of Retina and Optic Disc Diseases

- Treatment Principles for Diseases of the Optic Nerve and Retina

- Differential Diagnosis of Common Funduscopic Findings

- General Prevention and When to Seek Specialist Care

- References

Understanding the Retina and Optic Disc: Anatomy and Function

The retina and the optic nerve (specifically the optic disc or nerve head) are critical structures for vision. Ophthalmoscopic examination of a patient's eye allows for direct visualization of these components, providing invaluable insights into various local ocular pathologies as well as manifestations of systemic and neurological diseases.

Anatomy and Visual Pathway

The retina is the light-sensitive neural tissue lining the back of the eye. It contains photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) that convert light into electrical signals. These signals are processed by other retinal neurons (bipolar, horizontal, amacrine, and ganglion cells). The optic nerve is formed by the convergence of axons from these retinal ganglion cells, all gathering at the optic disc (optic nerve head), which is the point where the optic nerve exits the eyeball. This area is also known as the "blind spot" as it lacks photoreceptors.

From the optic disc, the optic nerve travels posteriorly within the orbit (retrobulbar portion), passes through the optic canal into the cranial cavity (middle cranial fossa), and then fibers from both optic nerves partially decussate (cross over) at the optic chiasm, located near the sella turcica (which houses the pituitary gland). After this partial crossing, the bundles of nerve fibers continue as the optic tracts, which primarily synapse in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. From there, visual information is relayed via the optic radiations to the primary visual cortex in the occipital lobe for conscious perception.

Vascular Supply and Clinical Implications of Occlusion

The retina and optic nerve are supplied by branches of the ophthalmic artery, itself a branch of the internal carotid artery. The central retinal artery enters the optic nerve and branches out to supply the inner retinal layers, while the optic nerve head and outer retina have additional supply from the short posterior ciliary arteries (circle of Zinn-Haller).

Occlusion (blockage) of these vessels can lead to severe visual impairment. For instance, in approximately 25% of cases involving clinically manifested occlusion of the internal carotid artery, patients may experience amaurosis fugax – transient, episodic monocular (one eye) blindness or visual disturbance. This is a critical warning sign, as it indicates a high probability of impending permanent blindness or stroke if the underlying vascular disease is not addressed. Patients describing amaurosis fugax might report a sensation of a "shadow" or "curtain" descending, ascending, or crossing their field of view, or a loss of peripheral parts of the visual field. They may also complain of blurred vision or transient dimming of vision in the affected eye, or the absence of the upper or lower half of the visual field. These symptoms typically persist for only a few minutes. Less commonly, but with more severe consequences, a stroke affecting the internal carotid artery can lead to simultaneous occlusion of the ophthalmic artery or the central retinal artery, resulting in sudden, profound, and often permanent vision loss in one eye.

Common Diseases and Pathologies of the Optic Nerve and Retina Leading to Visual Impairment

A multitude of pathological conditions can affect the optic nerve and retina, arising from diverse origins and differing in their localization and the nature of the pathological process. A comprehensive neurological and ophthalmological examination, considering these factors, is crucial for building an effective treatment plan.

Retinal Vascular Lesions and Retinopathies

Most pathological conditions affecting the body systemically or locally within the eye can cause retinal vascular lesions. Retinal vascular involvement can lead to varying degrees of visual impairment, up to and including blindness.

Hypertensive Retinopathy

The severity of changes in the retinal arteries in hypertensive retinopathy is directly associated with the level of systemic blood pressure. It is often staged:

- Stage I: Moderate generalized or focal narrowing of retinal arterioles ("silver wire" or "copper wire" appearance due to increased light reflex from thickened arterial walls) and mild arteriovenous (AV) nicking are noted.

- Stage II: More pronounced arteriolar narrowing and AV crossing changes (Gunn's sign, Salus' sign). Solid (hard) exudates (lipid deposits) and streak-like (flame-shaped) hemorrhages may appear.

- Stage III: Characterized by retinal edema, more extensive hemorrhages, and foci of nerve fiber layer infarcts appearing as "cotton wool spots."

- Stage IV (Malignant Hypertensive Retinopathy): Includes all signs of Stage III, and crucially, edema of the optic nerve head (papilledema). An accumulation of hard exudates in the macular region, often in a star-shaped pattern (macular star), can also be present.

Lesions in the form of cotton wool spots on retinal examination are hallmarks of accelerated or malignant hypertension but can also be found in conditions like severe anemia, leukemia, collagen vascular diseases (e.g., lupus), dysproteinemias, infective endocarditis, and diabetes mellitus.

Diabetic Retinopathy

A common microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus, divided into two main types:

- Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (NPDR) (formerly "exudative retinopathy"): Characterized by the formation of microaneurysms, dot-blot and flame-shaped hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, hard exudates, intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMA - bypass microvessels inside the retina), and venous beading or bleeding. Macular edema can occur at any stage and is a major cause of vision loss.

- Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (PDR): Characterized by neovascularization (growth of new, abnormal blood vessels) on the optic disc, retina, or iris, and macular edema. These new vessels are fragile and can lead to vitreous hemorrhage and tractional retinal detachment, significantly decreasing visual acuity (often to 20/200 or worse). Panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) is a laser treatment successfully used to slow the progression of PDR and prevent blindness. Anti-VEGF injections are also a mainstay.

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion (CRAO)

Embolism or thrombosis (occlusion) of the central retinal artery or its branches causes a retinal infarction (ischemic stroke of the retina). This typically leads to sudden, profound, and often permanent painless vision loss or blindness on the side of the ischemic retinal injury. Ophthalmoscopic findings in acute CRAO include:

- Marked, diffuse retinal opacification or whitening (milky white appearance) due to ischemic edema.

- A "cherry-red spot" at the macula, where the thin fovea allows visualization of the underlying, normally perfused choroid, contrasting with the pale retina.

- Uneven narrowing or "boxcarring" (segmentation) of blood flow in retinal arterioles. Retinal veins may also appear narrowed.

CRAO is a true ophthalmic emergency. Immediate measures to enhance blood flow and dislodge the embolus (e.g., ocular massage, anterior chamber paracentesis to lower intraocular pressure, carbogen inhalation) are attempted, but prognosis is often poor. If atheromatous changes are detected in the internal carotid artery on the affected side, aorta, or heart, an embolic source for CRAO is suggested. CRAO can also develop in conditions like giant cell (temporal) arteritis, atherosclerosis, collagen vascular diseases, or conditions accompanied by increased blood viscosity or vasospasm.

Monocular, transient visual impairment (amaurosis fugax) may herald an impending CRAO or ischemic stroke. Patients experiencing such symptoms require urgent hospitalization and evaluation by a neurologist and potentially a vascular neurosurgeon or interventionalist.

Venous Retinopathies and Occlusions

These can also cause visual impairment. Occlusion (blockage) of the central retinal vein (CRVO) or its branches (BRVO) is often accompanied by arterial hypertension, diabetes, glaucoma, or hyperviscosity states. Retinopathy with venostasis (obstruction of venous outflow) can be caused by a decrease in retinal perfusion pressure. This pressure reduction can be facilitated by:

- Occlusive lesions (embolism or stenosis) of the ipsilateral carotid artery.

- Pulseless disease (Takayasu's arteritis).

- Hyperviscosity syndromes like macroglobulinemia or polycythemia.

CRVO typically presents with sudden, painless vision loss, extensive retinal hemorrhages in all four quadrants ("blood and thunder" fundus), venous dilation and tortuosity, cotton wool spots, and macular edema.

Systemic Coagulopathies and Retinal Hemorrhages

Systemic coagulopathies, such as thrombocytopenia (low platelets) or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), can lead to retinal hemorrhages or clotting of blood in capillaries, particularly those located in the macular region. Severe systemic coagulopathy is sometimes accompanied by hemorrhage into the choroid itself, potentially causing serous retinal detachment. Patients may complain of blurred images or local loss of visual field (scotoma).

Rare Retinal Vascular Anomalies

These are uncommon but can cause visual disturbances:

- Telangiectasias (e.g., Coats' disease): Characterized by abnormal, dilated retinal capillaries that leak fluid and lipids.

- Retinal Angiomatosis (e.g., Von Hippel-Lindau disease - Hippel's disease refers to the retinal angioma component): Development of retinal hemangioblastomas.

- Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs): Such as cavernous retinal hemangiomas or racemose angiomas (e.g., Wyburn-Mason syndrome, which involves AVMs of the retina, brain, and face).

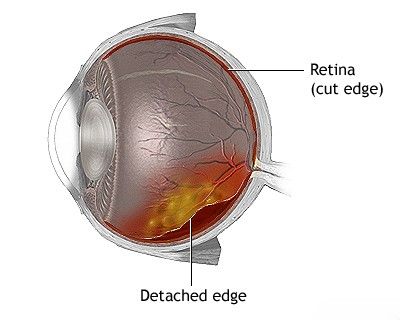

Retinal Detachment and Rupture

In addition to vascular lesions, other retinal changes can severely impair vision. Among the most significant is retinal detachment, where the neurosensory retina separates from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). This can be caused by retinal tears or breaks (rhegmatogenous), traction from fibrovascular membranes (tractional, e.g., in PDR), or exudation of fluid under the retina (exudative/serous, e.g., from tumors or inflammation). Symptoms include sudden onset of floaters, flashes of light (photopsias), and a curtain-like peripheral visual field loss that can progress to involve central vision. Retinal detachment is an ophthalmic emergency requiring prompt surgical repair to prevent permanent vision loss.

Retinal Degenerations

Several types of retinal degeneration exist, leading to progressive vision loss.

Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP)

With retinitis pigmentosa, there is a hereditary degeneration primarily affecting the photoreceptor layer (rods more than cones initially) and the adjacent retinal pigment epithelium. RP of the eye is typically accompanied by early loss of night vision (nyctalopia) and progressive impairment of peripheral vision (tunnel vision), eventually leading to loss of central vision in advanced stages. Characteristic funduscopic findings include optic disc pallor, attenuated retinal arterioles, and mid-peripheral retinal pigment deposits ("bone spicules"). Retinal degeneration in RP can also develop as part of certain systemic diseases or syndromes, such as:

- Abetalipoproteinemia (Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome)

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (e.g., Batten-Mayou disease)

- Refsum disease

- Kearns-Sayre syndrome (a mitochondrial myopathy)

- Usher syndrome (RP with congenital hearing loss)

Degeneration of Bruch's Membrane and Angioid Streaks

Bruch's membrane is a layer separating the RPE from the choroid. Degeneration and breaks in Bruch's membrane can lead to the formation of angioid streaks – irregular, crack-like lines that radiate from the optic disc towards the equator. Angioid streaks are often a sign of extensive degenerative changes occurring in elastic connective tissue systemically and can be seen in conditions such as:

- Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- Paget's disease of bone

- Lead poisoning (historically)

- Familial hyperphosphatemia

- Sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Complications of angioid streaks include choroidal neovascularization and subretinal hemorrhage, which can cause vision loss.

Drug-Induced Retinal Degenerations

- Degeneration of the Outer Retinal Layers (Photoreceptors/RPE): Can occur as a complication of taking certain medications, such as phenothiazine drugs (e.g., thioridazine, chlorpromazine in high doses). These drugs can bind to melanin in the pigment layer and cause toxicity. Patients taking such drugs long-term, especially at high doses, require regular ophthalmological monitoring, including color perimetry with red and white objects, to detect early signs of outer retinal layer degeneration.

- Degeneration of the Inner Retinal Layers (Ganglion cells, Bipolar cells): Can be a side effect of drugs like chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine (used for malaria and autoimmune diseases), leading to a characteristic "bull's-eye" maculopathy. Quinine toxicity can also affect inner retinal layers.

Optic Disc Pathologies

Elevation or swelling of the optic disc can be caused by various factors, including:

- Papilledema: As described earlier, non-inflammatory disc edema due to increased intracranial pressure.

- Papillitis (Anterior Optic Neuritis): Inflammatory swelling of the optic disc itself (see section #2-2).

- Optic Disc Drusen: Congenital, often bilateral, hyaline-like calcified deposits within the optic nerve head, which can mimic disc edema ("pseudo-edema"). They can sometimes cause peripheral visual field defects.

- Infiltration of the Optic Disc: By malignant cells (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma), granulomatous inflammation (e.g., sarcoidosis), or infection.

- Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AION): Swelling of the disc in the acute phase.

True edema of the optic nerve head (papilledema) is caused by swelling of axons and stasis (congestion) of axoplasmic flow, developing with an increase in intracranial pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This increased ICP is transmitted via the CSF in the subarachnoid space surrounding the optic nerve along its path from the cranial cavity to the orbit. As noted, visual acuity at the beginning of papilledema may be only slightly decreased or normal, with transient visual obscurations, visual field narrowing (especially enlargement of the blind spot). Vascular changes (hyperemia, venous stasis, hemorrhages) with optic disc edema are often secondary to the axoplasmic stasis. The presence of a spontaneous venous pulsation on the disc typically indicates that intracranial pressure is not significantly elevated (though its absence is not always pathological).

Pseudo-edema of the optic discs refers to congenital swelling or elevation of the discs due to factors like buried optic disc drusen or high hyperopia (which can make the disc appear elevated and crowded).

Papillitis, as an inflammatory swelling of the disc associated with optic neuritis, typically leads to early and significant loss of vision. It can develop in inflammatory processes directly affecting the optic disc, with optic nerve demyelination (as in multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica), with certain degenerations of the optic disc (e.g., Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy can sometimes have initial disc swelling), with infiltration of the optic disc by malignant cells, or with vascular lesions primarily affecting the optic disc.

It is important to distinguish papillitis from retrobulbar neuritis. Retrobulbar neuritis is characterized by foci of demyelination or inflammation in the optic nerve posterior to the globe (visible on high-field MRI), which, at the onset of the disease, are often not accompanied by visible changes in the fundus or the optic nerve head itself (disc appears normal). Retrobulbar neuritis leads to vision loss and often an afferent pupillary defect (Marcus Gunn pupil). Comparison of the direct pupillary reaction to light with the consensual (indirect) reaction is important for localizing a lesion of the afferent visual pathway. The swinging flashlight test is used to detect this reflex; a Marcus Gunn pupil is characterized by a paradoxical dilation of the pupil when light is swung from the unaffected eye to the affected eye, indicating that the indirect (consensual) reaction to light in the sound eye is stronger than the direct reaction in the affected eye.

Optic Neuropathy (Non-inflammatory)

Retrobulbar neuritis must be differentiated from functional (non-organic) vision loss, such as that occurring in some patients with hysteria. Binocular vision in such patients typically does not suffer objectively, and there is no afferent pupillary defect. A history of trauma, drug abuse, exposure to toxic substances, or alcoholism is important in the diagnostic workup of optic neuritis. In young people with idiopathic optic neuritis (inflammatory or retrobulbar), the risk of subsequently developing multiple sclerosis is approximately 30–50% over several years. In the elderly, a common cause of decreased visual acuity and visual field loss is optic nerve infarction (anterior ischemic optic neuropathy - AION). AION occurs in older individuals, often associated with giant cell (temporal) arteritis (arteritic AION), or more commonly, with non-arteritic arteriosclerotic risk factors (NAION), or rarely, embolism to the posterior ciliary arteries.

Optic Disc Atrophy

Most optic nerve lesions eventually lead to some degree of optic atrophy, characterized by discoloration (pallor) of the optic nerve head. There are three main reasons or types of optic disc pallor/atrophy:

- Hereditary familial optic atrophy (e.g., Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, dominant optic atrophy).

- Primary optic atrophy: Develops as a direct result of the death of retinal ganglion cells and their axons without preceding disc swelling (e.g., from compression, trauma, glaucoma, toxic/nutritional causes). The disc appears pale with sharp margins.

- Secondary optic atrophy: Develops after prolonged papillitis (optic neuritis involving the disc) or chronic edema of the optic nerve head (papilledema). The disc appears pale, often with blurred margins, gliosis (scar tissue), and sometimes sheathing of retinal vessels.

Macular Changes and Diseases

The macula is the central region of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed central vision and color vision. Diseases affecting the macula (maculopathies) often lead to significant visual impairment.

- Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD): A leading cause of irreversible vision loss in older adults. Exists in dry (atrophic) and wet (neovascular/exudative) forms.

- Diabetic Macular Edema (DME): Swelling of the macula due to leakage from damaged blood vessels in diabetic retinopathy.

- Cystoid Macular Edema (CME): Macular swelling with cyst-like spaces, can occur after eye surgery, with uveitis, retinal vein occlusions, or certain medications.

- Macular Hole: A full-thickness defect in the fovea.

- Epiretinal Membrane (Macular Pucker): A thin sheet of scar tissue that forms on the surface of the macula, causing distortion.

- Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (CSCR): Accumulation of fluid under the neurosensory retina in the macula.

- Hereditary Macular Dystrophies: E.g., Stargardt disease, Best disease.

- As mentioned, macular changes occur in the childhood form of Tay-Sachs familial amaurotic idiocy (cherry-red spot). In the juvenile forms of amaurotic idiocy (e.g., Batten disease), patients often develop pigmentary degeneration of the retina, particularly in the central regions, along with optic atrophy.

Diagnosis of Retina and Optic Disc Diseases

Diagnosis requires a comprehensive approach, including detailed history, visual acuity testing, visual field testing (perimetry), ophthalmoscopy, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, fluorescein angiography, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and sometimes electroretinography (ERG) or visual evoked potentials (VEP). Systemic workup is often necessary to identify underlying causes.

Treatment Principles for Diseases of the Optic Nerve and Retina

The neurological and ophthalmological treatment for diseases affecting the optic nerve and retina is highly individualized by the attending physician for each specific case. Treatment strategies depend on the underlying cause, severity, and acuity of the condition. It can encompass a complex array of conservative procedures, medical therapies, and, in certain instances, surgical interventions.

General principles include:

- Addressing the Underlying Cause: This is paramount. For example, controlling blood pressure in hypertensive retinopathy, managing blood sugar in diabetic retinopathy, treating infections causing optic neuritis, or surgically decompressing the optic nerve if compressed by a tumor (e.g., neurolysis of the nerve trunk from a scar or meningioma).

- Reducing Inflammation: Corticosteroids (oral, intravenous, or intravitreal) are often used for inflammatory conditions like optic neuritis or uveitis.

- Controlling Intraocular Pressure: In glaucoma, medications or surgery are used to lower eye pressure and prevent further optic nerve damage.

- Anti-VEGF Therapy: Intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents are a mainstay for wet AMD, diabetic macular edema, and retinal vein occlusions to reduce neovascularization and edema.

- Laser Photocoagulation: Used in diabetic retinopathy (panretinal photocoagulation) to reduce neovascularization, and for sealing retinal tears or treating macular edema.

- Vitrectomy Surgery: For conditions like vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, macular holes, or epiretinal membranes.

- Supportive and Rehabilitative Therapies:

- Low Vision Aids: For patients with significant, irreversible vision loss.

- Vitamins: B-group vitamins ("B"), Vitamin C ("C"), and Vitamin E ("E") are often prescribed as general neurotrophic or antioxidant support, though specific evidence varies by condition (e.g., AREDS formula for AMD).

- Antiviral Drugs: If a viral infection is the confirmed cause (e.g., CMV retinitis).

- Hormones (Corticosteroids): As systemic or local anti-inflammatory agents.

- Homeopathic Remedies: Some patients explore these, but their efficacy is not scientifically validated for most serious optic nerve and retinal diseases.

- Acupuncture: Considered by some to be very effective as an adjunctive therapy for conditions like optic neuritis, aiming to modulate inflammation and promote nerve function.

- Stimulation of the Optic Nerve and Oculomotor Muscles / Physiotherapy: Various forms of neurostimulation and physiotherapy are sometimes explored with the aim of accelerating vision restoration, though their established roles and efficacy vary greatly depending on the specific disease of the optic nerves or retina.

The duration of neurological and ophthalmological treatment, and its frequency, are dictated by the functional state of the optic nerve and retina, and the extent to which lost visual function (e.g., light sensitivity, acuity, visual field) is restored or stabilized.

Differential Diagnosis of Common Funduscopic Findings

A structured approach is needed to differentiate the myriad causes of vision loss and abnormal fundus findings. The following table provides a detailed differential diagnosis for common findings on funduscopic examination:

| Funduscopic Finding | Common Causes / Conditions | Key Differentiating Features / Associated Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Optic Disc Edema (Papilledema if due to ICP) | Increased intracranial pressure (tumor, hydrocephalus, IIH), Hypertensive crisis, Optic neuritis (papillitis), AION, Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), Compressive optic neuropathy. | Headache, nausea/vomiting, transient visual obscurations (with ICP). Vision loss (often sudden in AION/CRVO/neuritis). Pain with eye movement (neuritis). RAPD (if unilateral or asymmetric). |

| Optic Disc Pallor (Optic Atrophy) | Previous optic neuritis or papilledema, Glaucoma, Chronic compressive lesions, Ischemic optic neuropathy (late), Hereditary optic neuropathies, Toxic/Nutritional optic neuropathy. | Gradual or previous sudden vision loss, visual field defects, impaired color vision. History of preceding event or condition. |

| Retinal Hemorrhages | Diabetic retinopathy, Hypertensive retinopathy, Retinal vein occlusion, Anemia, Leukemia, Trauma, Age-related macular degeneration (wet), High altitude retinopathy. | Pattern of hemorrhage (flame, dot-blot, pre-retinal), associated vascular changes, exudates, neovascularization. Systemic disease history. |

| Cotton Wool Spots | Hypertension, Diabetes, HIV retinopathy, SLE, Severe anemia, CRVO. | Fluffy white retinal lesions (nerve fiber layer infarcts). Often associated with other signs of vascular disease. |

| Macular Changes (Edema, Exudates, Drusen, Hemorrhage) | Age-related macular degeneration, Diabetic macular edema, Cystoid macular edema (post-op, uveitis), Central serous chorioretinopathy, Macular hole, Epiretinal membrane. | Central vision loss, metamorphopsia (distortion), scotoma. OCT is key for diagnosis. |

| Cherry-Red Spot (Macula) | Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), Tay-Sachs disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Other lysosomal storage diseases. | Sudden profound vision loss (CRAO). Neurological regression in infants (storage diseases). |

| Retinal Vascular Attenuation/Sclerosis | Hypertension, Arteriosclerosis, Retinitis pigmentosa (late stage). | Narrowed arterioles, increased light reflex ("copper/silver wiring"), AV nicking. Peripheral field loss, night blindness (in RP). |

Key considerations include differentiating between:

- Optic nerve versus retinal pathology.

- Inflammatory versus ischemic versus compressive versus degenerative versus neoplastic causes.

- Acute versus chronic presentations.

- Unilateral versus bilateral involvement.

General Prevention and When to Seek Specialist Care

Prevention of many optic nerve and retinal diseases involves:

- Regular comprehensive eye examinations.

- Good control of systemic conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

- Avoiding smoking.

- Wearing UV protective eyewear.

- Eating a healthy, balanced diet.

- Using eye protection during hazardous activities.

Immediate consultation with an ophthalmologist, neuro-ophthalmologist, or neurologist is critical for any sudden vision loss, new visual field defects, persistent flashes or floaters, eye pain associated with vision change, or unexplained progressive visual decline. Early diagnosis and intervention are key to preserving vision.

References

- Yanoff M, Duker JS. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2019. (Comprehensive textbook).

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC). Section 5: Neuro-Ophthalmology. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology. (Published annually).

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC). Section 12: Retina and Vitreous. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology. (Published annually).

- Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Kerrison JB. Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams https://www.w3schools.com/html/html_entities.asp Wilkins; 2005.

- Foroozan R, Buono LM, Savino PJ, Sergott RC. Acute demyelinating optic neuritis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002 Dec;13(6):375-80.

- Hayreh SS. Ischemic optic neuropathies. Springer; 2011.

- Wong TY, Mitchell P. Hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004 Nov 25;351(22):2310-7.

- Optic Neuritis Study Group. The 15-year cumulative risk of multiple sclerosis among patients with optic neuritis. Neurology. 2008 Jun 10;70(24 Pt 2):2383-9.

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001 Oct;119(10):1417-36.

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Spinal disc herniation

- Pain in the arm and neck (trauma, cervical radiculopathy)

- The eyeball and the visual pathway:

- Anatomy of the eye and physiology of vision

- The visual pathway and its disorders

- Eye structures and visual disturbances that occur when they are affected

- Retina and optic disc, visual impairment when they are affected

- Impaired movement of the eyeballs

- Nystagmus and conditions resembling nystagmus

- Dry Eye Syndrome

- Optic nerve and retina:

- Compression neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Edema of the optic disc (papilledema)

- Ischemic neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Meningioma of the optic nerve sheath

- Optic nerve atrophy

- Optic neuritis in adults

- Optic neuritis in children

- Opto-chiasmal arachnoiditis

- Pseudo-edema of the optic disc (pseudopapilledema)

- Toxic and nutritional optic neuropathy

- Neuropathies and neuralgia:

- Diabetic, alcoholic, toxic and small fiber sensory neuropathy (SFSN)

- Facial nerve neuritis (Bell's palsy, post-traumatic neuropathy)

- Fibular (peroneal) nerve neuropathy

- Median nerve neuropathy

- Neuralgia (intercostal, occipital, facial, glossopharyngeal, trigeminal, metatarsal)

- Post-traumatic neuropathies

- Post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy

- Post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy

- Radial nerve neuropathy

- Tibial nerve neuropathy

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Ulnar nerve neuropathy

- Tumors (neoplasms) of the peripheral nerves and autonomic nervous system (neuroma, sarcomatosis, melanoma, neurofibromatosis, Recklinghausen's disease)

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Ulnar nerve compression in the cubital canal