Facial nerve neuritis (Bell's palsy, post-traumatic neuropathy)

![]() Attention! Please do not confuse the diagnosis of "facial nerve neuritis" (affecting facial muscles and expression) described in this article with the distinct diagnoses of "trigeminal neuralgia" (causing facial pain) or "trigeminal neuritis" (inflammation of the trigeminal nerve, primarily causing sensory disturbances or weakness of chewing muscles).

Attention! Please do not confuse the diagnosis of "facial nerve neuritis" (affecting facial muscles and expression) described in this article with the distinct diagnoses of "trigeminal neuralgia" (causing facial pain) or "trigeminal neuritis" (inflammation of the trigeminal nerve, primarily causing sensory disturbances or weakness of chewing muscles).

Understanding Facial Nerve Neuritis (Facial Palsy)

Neuritis of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) refers to an inflammation or damage affecting the nerve itself or its myelin sheath. This condition leads to a spectrum of motor, sensory (taste), and autonomic disturbances in the areas innervated by the facial nerve, most notably resulting in weakness or paralysis of the facial muscles (facial palsy) and subsequent facial distortion.

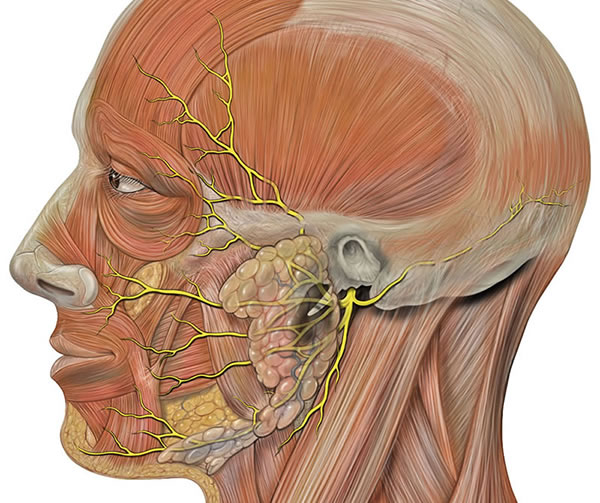

Definition and Anatomy

Facial nerve neuritis implies an inflammatory process, while "facial neuropathy" is a broader term encompassing any disorder of the facial nerve. The facial nerve is a mixed nerve, containing motor fibers that control the muscles of facial expression, parasympathetic fibers innervating lacrimal, submandibular, and sublingual glands, and special sensory fibers for taste from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Damage or inflammation of the facial nerve can occur at various points along its complex anatomical course:

- Intracranially: From its origin in the brainstem (pons) to its entry into the internal acoustic meatus.

- Intratemporally (within the temporal bone): As it passes through the facial canal (fallopian canal), a long and narrow bony channel, near structures of the middle and inner ear. This segment includes the geniculate ganglion.

- Extracranially: After it exits the skull via the stylomastoid foramen and branches within the parotid gland to supply the facial muscles.

Common Causes and Mechanisms

Neuritis of the facial nerve can result from various pathological processes:

- Idiopathic (Bell's Palsy): This is the most common cause of acute unilateral facial paralysis. While termed idiopathic (unknown cause), it is strongly believed to be associated with viral infections, particularly Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 (HSV-1), leading to inflammation and swelling of the nerve within the narrow facial canal.

- Infectious Causes:

- Herpes Zoster Oticus (Ramsay Hunt Syndrome): Reactivation of Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) in the geniculate ganglion, causing facial palsy, ear pain, and vesicular rash in the ear canal or auricle.

- Otitis Media or Mastoiditis: Infections of the middle ear or mastoid can spread to involve the facial nerve within the temporal bone.

- Lyme disease.

- Other viral infections (e.g., influenza, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus).

- Trauma (Post-Traumatic Facial Neuropathy):

- Fractures of the temporal bone pyramid or base of the skull resulting from traumatic brain injury (TBI).

- Surgical trauma during brain surgery (e.g., acoustic neuroma removal), parotid surgery, mastoid surgery, or plastic surgery (e.g., facelift).

- Facial lacerations transecting nerve branches.

- Compression:

- Tumors of the cerebellopontine angle (e.g., acoustic neuroma/vestibular schwannoma, meningioma), brainstem tumors, or tumors within the temporal bone or parotid gland compressing the facial nerve.

- Vascular compression by an aneurysm (e.g., of the vertebral artery or posterior inferior cerebellar artery) or an aberrant blood vessel.

- Toxic/Metabolic Causes:

- Diabetes mellitus (can cause cranial neuropathies).

- Guillain-Barré syndrome (can involve bilateral facial palsy).

- Sarcoidosis (e.g., Heerfordt's syndrome - uveoparotid fever).

- Certain toxins (rarely).

The tendency to develop facial nerve neuritis, particularly Bell's palsy, with viral infections, colds, hypothermia, or general depletion of the body is primarily attributed to the anatomical feature of the facial nerve's long course within the narrow, unyielding bony facial canal. Inflammatory swelling (edema) of the nerve within this confined space can lead to compression, ischemia (reduced blood flow), and impaired nerve function (conduction block or axonal damage).

Most often in neurological practice, idiopathic facial nerve neuritis (Bell's palsy), often presumed viral (e.g., herpes virus), results in unilateral paresis or paralysis of facial muscles. The herpes virus (HSV-1 or VZV) can become latent in nerve ganglia, including the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve. During reactivation, the virus can damage the myelin sheath and/or axons of the facial nerve, causing edema as part of the inflammatory response. This leads to impaired conduction of nerve impulses from the brain to the facial muscles, manifesting as weakness (paresis) or complete paralysis.

Clinical Manifestations and Symptoms

The specific symptoms depend on the level (location along the nerve's course) and severity of the facial nerve damage. Manifestations can include:

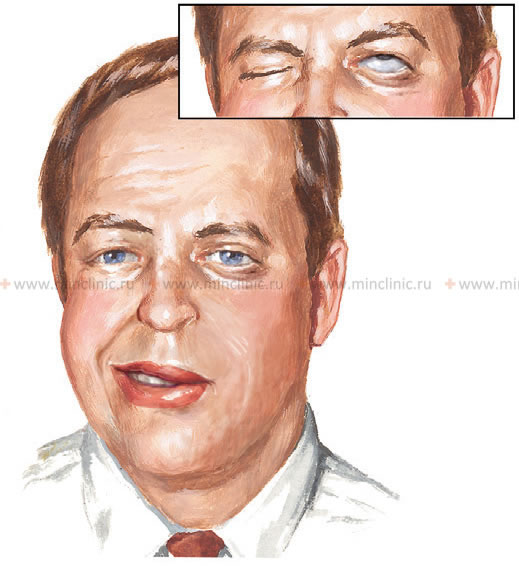

- Motor Deficits (Facial Muscle Weakness/Paralysis):

- Inability to wrinkle the forehead on the affected side.

- Difficulty or inability to close the eye completely (lagophthalmos), leading to eye dryness and irritation. The eyeball may turn upward when attempting to close the eye (Bell's phenomenon), exposing the sclera.

- Drooping of the eyebrow and corner of the mouth on the affected side.

- Flattening of the nasolabial fold.

- Inability to smile, show teeth, or puff out the cheek on the affected side. The lower eyelid and lower lip may be slightly lowered or sag.

- Difficulty with speech articulation (dysarthria) due to lip weakness.

- Drooling or food collecting between the cheek and gum.

- Sensory Changes:

- Altered or lost taste sensation (ageusia/dysgeusia) on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue on the affected side (if the chorda tympani branch is involved).

- Pain in or behind the ear (otalgia), or on the face, may precede or accompany the paralysis.

- Numbness or altered sensation on the lateral surface of the tongue or parts of the face (less common, as the facial nerve is primarily motor, but sensory fibers from other nerves can be affected by the same underlying pathology or inflammation).

- Autonomic Changes:

- Decreased tearing (dry eye) or, paradoxically, excessive tearing (epiphora, due to impaired eyelid function and tear drainage) if the greater superficial petrosal nerve is involved.

- Altered salivation (dry mouth or excessive salivation).

- Hyperacusis (increased sensitivity to sound) due to paralysis of the stapedius muscle in the middle ear (if the nerve to stapedius is affected).

Facial nerve neuritis results in impaired conduction of nerve impulses from the brain to the muscles of facial expression, which manifests as the signs and symptoms of paresis or paralysis described above.

With facial nerve neuritis, the patient typically cannot close the eye on the affected side (the eyeball turns upward, exposing the sclera – Bell's phenomenon – because the eyelids do not close effectively), wrinkle the forehead, or show teeth properly when attempting to smile. The lower eyelid and lower lip on the affected side may also be slightly lowered or droop.

Diagnosis of Facial Nerve Neuritis

When diagnosing facial nerve neuritis and determining the type and extent of damage, a clear localization of the level of nerve injury is crucial. This requires a comprehensive diagnostic approach.

Clinical Evaluation and Neurological Examination

A thorough neurological examination is performed to assess:

- The pattern and severity of facial muscle weakness (e.g., using a grading scale like House-Brackmann).

- Presence of Bell's phenomenon.

- Taste sensation on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

- Hearing (for hyperacusis) and examination of the ear canal and tympanic membrane (especially if Ramsay Hunt syndrome or otitis media is suspected).

- Lacrimation and salivation (though direct testing is less common).

- Other cranial nerve functions and neurological signs to rule out central causes (e.g., stroke, brain tumor affecting the facial nucleus or supranuclear pathways).

- A detailed medical history focusing on onset of symptoms, preceding infections, trauma, risk factors for diabetes, Lyme disease, or tumors.

Electrodiagnostic Studies (ENG/EMG)

Electroneurography (ENG), also known as nerve conduction studies (NCS), and Electromyography (EMG) are valuable diagnostic tools:

- ENG/NCS: Measures the speed and amplitude of electrical impulses conducted along the facial nerve. It can help determine the severity of nerve damage (conduction block vs. axonal loss - neurapraxia, axonotmesis, neurotmesis) and provide prognostic information. Comparisons are made between the affected and unaffected sides. Studies are typically performed 7-10 days after onset for optimal prognostic value.

- EMG: Records electrical activity in facial muscles. It can detect signs of denervation (e.g., fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves) if axonal damage has occurred, and later, signs of reinnervation (e.g., nascent motor unit potentials).

These tests help to assess the degree of nerve damage and monitor recovery.

Imaging Studies (MRI/CT)

Imaging is not routinely required for typical Bell's palsy but is indicated if:

- The presentation is atypical (e.g., gradual onset, involvement of other cranial nerves, bilateral facial palsy, no improvement after several weeks).

- A specific underlying cause is suspected (e.g., tumor, stroke, temporal bone fracture).

- MRI of the Brain and Facial Nerve (with gadolinium contrast): The preferred imaging modality to visualize the facial nerve along its course, detect inflammation (enhancement), tumors, or demyelinating lesions.

- CT Scan of the Brain and Temporal Bones: Useful for assessing bony anatomy, particularly in cases of trauma (temporal bone fractures) or suspected cholesteatoma.

Other tests may include blood tests for Lyme disease, diabetes, sarcoidosis, or viral titers (e.g., for VZV if Ramsay Hunt syndrome is suspected).

Diagnosis of the level and severity of nerve damage in facial nerve neuritis, similar to investigations for any other peripheral nerve, is performed using electrodiagnostic studies like electroneurography (ENG/NCS) and electromyography (EMG). (The image demonstrates ENG principles using the sural nerve as an example).

Treatment of Facial Nerve Neuritis

The treatment for facial nerve neuritis is selected individually in each case, depending on the underlying cause, severity, and duration of symptoms. It often includes a combination of conservative outpatient procedures and medical management.

General Principles and Medical Management

- Corticosteroids: For Bell's palsy, a short course of oral corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) started within 72 hours of onset is recommended to reduce inflammation and improve the chances of full recovery.

- Antiviral Medications: For Bell's palsy, the addition of antiviral agents (e.g., acyclovir, valacyclovir) to corticosteroids is controversial, with some guidelines recommending it and others finding limited additional benefit over steroids alone. Antivirals are clearly indicated for Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus).

- Eye Care: Crucial if eyelid closure is incomplete (lagophthalmos) to prevent corneal dryness, abrasions, and ulceration. This includes:

- Frequent use of artificial tears (lubricating eye drops) during the day.

- Lubricating eye ointment at night.

- Taping the eyelid shut at night or using an eye patch or moisture chamber.

- Treatment of Underlying Cause: If a specific cause is identified (e.g., antibiotics for Lyme disease or otitis media, surgical removal of a tumor), it must be addressed.

- Pain Management: Analgesics for any associated pain (e.g., otalgia).

- Vitamins: Vitamins of group "B" (B1, B6, B12), "C," and "E" are often prescribed for their neurotrophic and antioxidant properties, though strong evidence for significant benefit in acute facial palsy is limited.

- Homeopathic Remedies: Some patients explore homeopathic remedies, but their efficacy is not supported by robust scientific evidence.

Rehabilitative Therapies

- Physiotherapy (Facial Rehabilitation): Specific facial exercises, massage, and neuromuscular retraining techniques taught by a therapist can help improve muscle function, coordination, and reduce synkinesis (abnormal linked movements) during recovery. Physiotherapy is very effective in treating neuritis of the facial nerve.

- Acupuncture: Some studies and anecdotal evidence suggest acupuncture can be very effective in promoting recovery and alleviating symptoms in facial nerve neuritis, though more rigorous research is needed.

- Electrical Stimulation:

- Stimulation of the Facial Nerve and Facial Muscles: The use of electrical stimulation to maintain muscle tone or promote nerve regeneration is controversial. Some protocols include it, while others advise against it, especially in early stages, due to concerns it might promote synkinesis. Techniques like Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) are sometimes used.

- UHF (Ultra-High Frequency) Therapy: Application of UHF currents to the exit point of the facial nerve (stylomastoid foramen) has been used as a physiotherapy modality.

Acupuncture is considered a very effective adjunctive therapy in the treatment of facial nerve neuritis, potentially aiding in nerve recovery and symptom relief.

Physiotherapy, including targeted facial exercises and potentially electrical stimulation, plays a very effective role in the rehabilitation and treatment of facial nerve neuritis.

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) is one of the physiotherapy modalities used in the treatment protocol for facial nerve neuritis to aid in nerve recovery and muscle function.

Surgical Options (Rarely Indicated for Neuritis)

Surgical decompression of the facial nerve within the facial canal was historically performed for severe Bell's palsy with poor prognostic indicators on electrophysiologic testing, but its efficacy is controversial and it is rarely recommended today due to risks of surgical complications (hearing loss, further nerve damage). Surgery is primarily reserved for cases of facial palsy due to trauma with nerve transection (requiring nerve repair or grafting) or compression by a tumor (requiring tumor removal).

Psychological Support

The duration of treatment for facial nerve neuritis and its frequency (number of courses) is dictated by the state of nerve conduction recovery and the restoration of motor activity in the facial muscles (i.e., elimination of facial distortion due to asymmetry of the nasolabial fold, weakness of eyelid muscles). Treatment for a patient with facial nerve neuritis does not always require hospitalization; many treatment procedures can be easily performed on an outpatient basis in a well-equipped polyclinic or rehabilitation center. Hospitalization in a neurological department for uncomplicated facial nerve neuritis (like Bell's palsy) might sometimes aggravate the negative emotional background in a patient experiencing such a pronounced cosmetic defect (the appearance of a "skewed face" can be perceived very dramatically, especially by women). Psychological support and counseling can be beneficial.

For some patients, one course of treatment (e.g., 10-12 procedures performed daily or on a regular schedule) may be sufficient to completely restore lost nerve functions and facial muscle strength. Other patients may require longer treatment, with outpatient courses repeated several times throughout the year until maximum possible recovery is achieved.

Differential Diagnosis of Facial Weakness/Paralysis

It is crucial to differentiate Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial neuritis) from other causes of facial weakness or paralysis:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Bell's Palsy (Idiopathic Facial Palsy) | Acute onset of unilateral facial weakness/paralysis (upper and lower face); often post-viral; diagnosis of exclusion. May have taste changes, hyperacusis, ear pain. |

| Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (Herpes Zoster Oticus) | Facial palsy PLUS painful vesicular rash in ear canal/auricle, or on palate/tongue; often severe otalgia, hearing loss, vertigo. Caused by VZV. |

| Stroke (Central Facial Palsy) | Sudden onset; typically spares the forehead muscles (frontalis); associated with other neurological deficits (hemiparesis, aphasia, dysarthria). Upper motor neuron lesion. |

| Tumors (e.g., Acoustic Neuroma, Facial Nerve Schwannoma, Parotid Tumor) | Gradual onset of facial weakness (though can be acute with some malignant tumors); may have associated hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, or other cranial nerve deficits. Imaging (MRI) is key. |

| Lyme Disease | Can cause unilateral or bilateral facial palsy; history of tick bite, erythema migrans rash, arthralgias, carditis. Serological testing. |

| Otitis Media / Mastoiditis | Facial palsy associated with ear infection symptoms (otalgia, discharge, hearing loss). |

| Trauma (Temporal Bone Fracture, Facial Laceration) | Clear history of injury. Imaging for fractures. |

| Guillain-Barré Syndrome | Often ascending paralysis, can involve bilateral facial weakness; areflexia. CSF shows albuminocytologic dissociation. |

| Sarcoidosis / Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome | Sarcoidosis can cause facial palsy (Heerfordt's). Melkersson-Rosenthal: recurrent facial palsy, facial edema, fissured tongue. |

| Myasthenia Gravis | Fluctuating weakness, worse with activity, improves with rest; ptosis, diplopia common. Facial weakness can occur. Positive AChR antibodies, response to edrophonium/neostigmine. |

Prognosis and Potential Complications

Prognosis:

- Bell's Palsy: The majority of patients (around 70-85%) make a good to complete recovery, usually within weeks to a few months. Recovery often begins within 2-3 weeks. Poorer prognosis is associated with complete paralysis at onset, older age, severe pain, and certain electrophysiological findings (e.g., evidence of severe axonal degeneration).

- Other Causes: Prognosis depends on the underlying etiology and the extent of nerve damage. Traumatic or compressive neuropathies may have variable outcomes depending on the severity and timing of intervention.

Potential Complications/Sequelae:

- Incomplete Recovery: Persistent facial weakness or asymmetry.

- Synkinesis: Abnormal, involuntary linked movements of different facial muscle groups during voluntary movement (e.g., eye closure when smiling, mouth movement when blinking). This results from misdirected nerve regeneration.

- Contractures: Persistent muscle spasms or tightness in affected facial muscles.

- Crocodile Tears (Gustatory Lacrimation): Tearing while eating, due to aberrant nerve regeneration connecting salivary fibers to lacrimal gland.

- Corneal Complications: Exposure keratitis, corneal abrasions, or ulcers due to inability to close the eye properly (lagophthalmos) and reduced tear production.

- Psychological Impact: Facial asymmetry can lead to significant emotional distress, anxiety, and depression.

Prevention Strategies

While Bell's palsy is often idiopathic, some general preventive measures can be considered:

- Prompt Treatment of Infections: Early management of ear infections or viral illnesses like herpes zoster.

- Trauma Prevention: Using protective gear during activities that risk head or facial injury.

- Lyme Disease Prevention: Taking precautions against tick bites in endemic areas.

- Management of Systemic Conditions: Good control of diabetes or other conditions that can predispose to neuropathy.

When to Consult a Neurologist or ENT Specialist

It is crucial to seek medical attention promptly if you experience sudden onset of facial weakness or paralysis. Consultation with a neurologist or an ENT specialist (otolaryngologist) is recommended to:

- Confirm the diagnosis and rule out more serious underlying causes (e.g., stroke, tumor).

- Initiate appropriate medical treatment (e.g., corticosteroids for Bell's palsy) in a timely manner.

- Receive guidance on eye care to prevent corneal complications.

- Undergo electrodiagnostic testing if indicated for prognostic assessment.

- Be referred for facial physiotherapy or other rehabilitative therapies.

- Discuss management options for long-term sequelae if they occur.

Early and accurate diagnosis and management can significantly improve the outcome of facial nerve neuritis.

References

- Gilden DH. Bell's Palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 23;351(13):1323-31.

- Peitersen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;(549):4-30.

- Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell's palsy. BMJ. 2004 Sep 4;329(7465):553-7.

- Sweeney CJ, Gilden DH. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001 Aug;71(2):149-54.

- Gronseth GS, Paduga R; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline update: steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012 Nov 27;79(22):2209-13.

- Engström M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Axelsson S, Pitkäranta A, Hultcrantz M, Kanerva M, Hanner P, Jonsson L. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell's palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Nov;7(11):993-1000.

- Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell's palsy: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Oct 1;76(7):997-1002.

- Adour KK. Current concepts in neurology: diagnosis and management of facial paralysis. N Engl J Med. 1982 Aug 12;307(7):348-51.

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Spinal disc herniation

- Pain in the arm and neck (trauma, cervical radiculopathy)

- The eyeball and the visual pathway:

- Anatomy of the eye and physiology of vision

- The visual pathway and its disorders

- Eye structures and visual disturbances that occur when they are affected

- Retina and optic disc, visual impairment when they are affected

- Impaired movement of the eyeballs

- Nystagmus and conditions resembling nystagmus

- Dry Eye Syndrome

- Optic nerve and retina:

- Compression neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Edema of the optic disc (papilledema)

- Ischemic neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Meningioma of the optic nerve sheath

- Optic nerve atrophy

- Optic neuritis in adults

- Optic neuritis in children

- Opto-chiasmal arachnoiditis

- Pseudo-edema of the optic disc (pseudopapilledema)

- Toxic and nutritional optic neuropathy

- Neuropathies and neuralgia:

- Diabetic, alcoholic, toxic and small fiber sensory neuropathy (SFSN)

- Facial nerve neuritis (Bell's palsy, post-traumatic neuropathy)

- Fibular (peroneal) nerve neuropathy

- Median nerve neuropathy

- Neuralgia (intercostal, occipital, facial, glossopharyngeal, trigeminal, metatarsal)

- Post-traumatic neuropathies

- Post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy

- Post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy

- Radial nerve neuropathy

- Tibial nerve neuropathy

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Ulnar nerve neuropathy

- Tumors (neoplasms) of the peripheral nerves and autonomic nervous system (neuroma, sarcomatosis, melanoma, neurofibromatosis, Recklinghausen's disease)

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Ulnar nerve compression in the cubital canal