Nystagmus and conditions resembling nystagmus

- Understanding Nystagmus: Involuntary Eye Movements

- Key Types of Pathological Nystagmus

- Conditions Resembling Nystagmus (Saccadic Intrusions and Oscillations)

- Diagnosis of Nystagmus

- General Principles of Nystagmus Management

- Differential Diagnosis of Nystagmus by Type/Cause

- Importance of Neurological and Neuro-Ophthalmological Evaluation

- References

Understanding Nystagmus: Involuntary Eye Movements

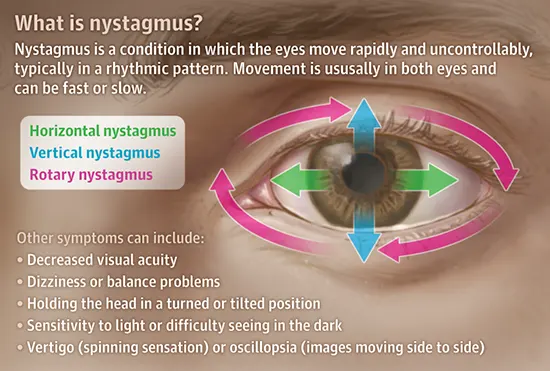

Nystagmus is characterized by repetitive, rhythmic, involuntary movements of the eyeballs that follow one after another. These movements can vary in direction (horizontal, vertical, torsional/rotary, or mixed), amplitude, and frequency.

Definition and Basic Types (Pendular vs. Jerk)

There are two primary types of nystagmus based on the waveform of the eye movements:

- Pendular Nystagmus: Characterized by smooth, sinusoidal oscillations of the eyes, where the movements are of equal velocity in both directions (like a pendulum).

- Jerk Nystagmus: Characterized by an alternation of a slow phase (slow drift of the eyes away from the target) and a corrective fast phase (a rapid saccadic movement bringing the eyes back to the target). By convention, the direction of jerk nystagmus is named after the direction of its fast phase.

Physiological vs. Pathological Nystagmus

In healthy individuals, nystagmus can occur as a normal physiological response under certain conditions:

- Vestibular Nystagmus: Induced by stimulation of the vestibular system (inner ear balance organs), such as during head rotation (e.g., caloric testing, rotational chair testing). The vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) drives this.

- Optokinetic Nystagmus (OKN): Elicited by tracking a succession of moving objects across the visual field (e.g., watching scenery from a moving train, or using an optokinetic drum).

- End-Point Nystagmus: Fine, jerky nystagmus that can occur in extreme lateral or upward gaze in some normal individuals, usually benign and unsustained.

Pathological nystagmus, on the other hand, occurs when the mechanisms responsible for maintaining steady gaze fixation and coordinating eye movements are damaged. The vestibular system, the optokinetic system, and the system for smooth pursuit (tracking targeted eye movements) normally interact to maintain a stable image on the retina. The neural integrator in the brainstem plays a crucial role in holding the eyes steady on an object. Damage to any of these complex systems, or their central connections, can lead to pathological nystagmus.

To determine the cause of nystagmus, a thorough patient anamnesis (medical history) is collected, including information about medication use (e.g., sedatives, anticonvulsants), alcohol consumption, history of head trauma, neurological diseases, or inner ear problems. This is followed by a complete examination of eye movements and a neurological assessment.

Associated Symptoms

Nystagmus itself refers to the involuntary eye movements. Patients with pathological nystagmus may also experience other symptoms, including:

- Decreased Visual Acuity: Difficulty seeing clearly due to the inability to maintain stable foveal fixation.

- Oscillopsia: An illusory sensation that the surrounding environment is moving, shaking, or oscillating. This is particularly common with acquired nystagmus.

- Vertigo (Spinning Sensation): Especially if the nystagmus is of vestibular origin.

- Dizziness or Balance Problems.

- Abnormal Head Posture (Null Point): Some individuals adopt a specific head turn or tilt to a position where the nystagmus intensity is minimized and vision is clearest (the "null point" or "null zone").

- Sensitivity to Light (Photophobia) or Difficulty Seeing in the Dark.

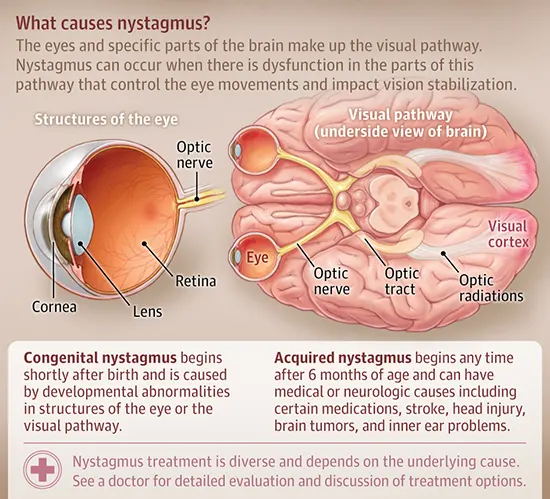

Causes of Nystagmus: An Overview

The eyes and specific parts of the brain (including the brainstem, cerebellum, and cerebral cortex) constitute the complex visual and oculomotor pathways. Nystagmus can occur when there is dysfunction in any part of this pathway that controls eye movements and impacts visual stabilization.

- Congenital Nystagmus: Often begins shortly after birth (typically within the first few months of life) and can be caused by developmental abnormalities in the structures of the eye (e.g., albinism, optic nerve hypoplasia, congenital cataracts, aniridia) or in the visual or oculomotor pathways. Some forms are idiopathic (infantile nystagmus syndrome).

- Acquired Nystagmus: Can begin at any time after the neonatal period and may have a wide range of medical or neurological causes, including:

- Inner ear problems (vestibular disorders like labyrinthitis, Meniere's disease, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo - BPPV).

- Head injury or trauma.

- Stroke (especially affecting the brainstem or cerebellum).

- Brain tumors (e.g., in the posterior fossa or brainstem).

- Multiple sclerosis or other demyelinating diseases.

- Certain medications (e.g., anticonvulsants like phenytoin, sedatives, lithium).

- Alcohol intoxication.

- Thiamine deficiency (Wernicke's encephalopathy).

- Neurodegenerative diseases.

The treatment for nystagmus is diverse and depends heavily on identifying and addressing the underlying cause. A thorough evaluation by a doctor (often a neurologist, neuro-ophthalmologist, or otolaryngologist) is essential to discuss diagnostic findings and appropriate treatment options.

Key Types of Pathological Nystagmus

In clinical practice, particularly for neurological patients, several distinct types of pathological nystagmus are recognized based on their characteristics and underlying mechanisms:

Congenital Nystagmus (Infantile Nystagmus Syndrome)

Congenital nystagmus typically presents within the first few months of life. It is often characterized by long-term, predominantly horizontal, conjugate (both eyes move together) eye movements, which can be pendular or jerky. In some cases, congenital nystagmus is associated with underlying damage to the afferent visual pathway (e.g., optic nerve hypoplasia, albinism, congenital cataracts, retinal dystrophies) leading to visual impairment. However, many cases are idiopathic (infantile nystagmus syndrome, INS), where no specific ocular or neurological cause is found, and visual acuity can range from near-normal to significantly reduced. The precise mechanism and localization of the lesion in idiopathic congenital nystagmus are often not fully known, but it is thought to involve instability in the oculomotor control systems responsible for gaze holding.

Labyrinthine-Vestibular Nystagmus (Peripheral and Central)

Damage or dysfunction of the vestibular apparatus (inner ear labyrinth and vestibular nerve - peripheral vestibular system) or its central connections in the brainstem and cerebellum leads to the appearance of vestibular nystagmus. This is typically a jerk nystagmus, characterized by a slow, smooth drift phase away from the intended gaze direction (driven by vestibular imbalance) and a corrective fast saccadic phase back towards the target. This combination forms a "sawtooth" pattern. The unidirectional movement of the slow phase of nystagmus reflects an instability or asymmetry in the tonic neuronal activity of the vestibular nuclei.

Damage to the semicircular canals of the inner ear (or their neural pathways) leads to a slow deviation of the eyeball towards the side of the lesioned semicircular canal (or away from the side of an overactive one), followed by a rapid compensatory movement (fast phase) in the opposite direction. As per convention, the direction of nystagmus is defined by the direction of its fast corrective phase.

This instability of vestibular tone usually leads to symptoms like vertigo (a sensation of spinning or rotation of oneself or the environment) and oscillopsia (an illusory movement or shaking of the surrounding objects) in the patient.

- Peripheral Vestibular Nystagmus: Arises from lesions of the labyrinth or vestibular nerve. It is almost always accompanied by damage to several semicircular canals simultaneously. This leads to an imbalance between signals entering the brain from individual semicircular canals. In such cases, nystagmus is often mixed (e.g., horizontal-torsional).

- With benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), the patient typically develops mixed vertical-torsional nystagmus triggered by specific head positions.

- With unilateral destruction of the labyrinth (e.g., vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis), the patient often has a mixed horizontal-torsional nystagmus beating away from the side of the lesion.

- Central Vestibular Nystagmus: Arises from lesions of the central vestibular connections in the brainstem or cerebellum. This causes a central imbalance between signals from the semicircular canals, or interrupts ascending vestibular or cerebellar-vestibular pathways. Central vestibular nystagmus may visually resemble nystagmus from semicircular canal lesions. However, purely vertical (upbeat or downbeat), purely torsional, or purely horizontal nystagmus that is present in primary gaze is more common with central lesions. Central vestibular nystagmus is often not suppressed by visual fixation, may change direction with gaze, or may be gaze-evoked. It can also be influenced by changes in head position.

Specific Forms: Downbeat, Upbeat, Horizontal Nystagmus

Three types of nystagmus related to labyrinthine-vestibular system dysfunction are particularly important for localizing the lesion:

- Downbeat Nystagmus: Characterized by a fast phase beating downwards. It is usually seen when the patient is looking straight ahead (primary position) and often worsens when looking laterally or slightly downwards. Downbeat nystagmus is often caused by lesions affecting the cervicomedullary junction or cerebellum, such as Arnold-Chiari malformation, platybasia, multiple sclerosis, cerebellar atrophy or degeneration, hydrocephalus, certain metabolic disorders (e.g., Wernicke's encephalopathy), or familial periodic ataxia. It can also occur as a toxic reaction to anticonvulsant drugs (e.g., phenytoin, carbamazepine) or lithium.

- Upbeat Nystagmus: Characterized by a fast phase beating upwards, often present in primary position. It is typically a consequence of damage to the anterior parts of the cerebellar vermis or diffuse brainstem lesions, as seen in Wernicke's encephalopathy, meningitis, brainstem encephalitis, or as a side effect of certain drugs.

- Primary Position Horizontal Nystagmus: Horizontal nystagmus (fast phase to the left or right) present when the patient is looking straight ahead is most commonly observed with acute unilateral damage to the peripheral vestibular system (labyrinth or vestibular nerve). It only sometimes occurs with central lesions like tumors of the posterior cranial fossa or Arnold-Chiari malformation.

Gaze-Evoked Nystagmus

Nystagmus that occurs only with purposeful eye movements, i.e., when the eyeballs deviate from the central (primary) position to an eccentric gaze position, is called gaze-evoked nystagmus. The inability to hold the eyes steady in an eccentric position (impaired gaze holding) is often due to damage to the neural integrator in the brainstem or cerebellum. Asymmetric, but conjugate (friendly), horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus can occur with unilateral cerebellar lesions or tumors of the cerebellopontine angle (e.g., acoustic neuroma/vestibular schwannoma). A common cause of symmetrical horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus is the use of sedative drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines, barbiturates) and anticonvulsants. Horizontal nystagmus in which the fast phase of the abducting eye (when the eyeball is moved outward) occurs with greater amplitude or slower speed than the adducting eye (when the eyeball is moved inward) is a form of dissociated nystagmus and is a characteristic sign of internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), indicating a lesion of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF).

Converging Pulsating Nystagmus (Nystagmus Retractorius)

Convergence-retraction nystagmus, which is aggravated by an attempt to look upwards, is characterized by pulsating, irregular, jerky saccadic movements of both eyeballs towards each other (convergence), often accompanied by retraction of the globes into the orbits. As a rule, convergence-retraction nystagmus is accompanied by other symptoms of damage to the dorsal midbrain (tectal region), forming part of Parinaud's syndrome (dorsal midbrain syndrome), which also includes upgaze palsy, pupillary light-near dissociation, and eyelid retraction.

Periodic Alternating Nystagmus (PAN)

In cases of periodic alternating nystagmus, the patient exhibits horizontal jerk nystagmus when looking straight ahead, which periodically (typically every 1-2 minutes) changes its direction (e.g., beating to the right for a period, then null phase, then beating to the left for a period). There may also be associated gaze-evoked nystagmus or downbeat nystagmus. PAN can be congenital (hereditary) or acquired. Acquired PAN can occur in association with craniovertebral abnormalities (e.g., Arnold-Chiari malformation), multiple sclerosis, cerebellar lesions, or as a result of anticonvulsant drug intoxication. In non-hereditary forms of PAN, treatment with baclofen can sometimes provide a positive effect by suppressing the nystagmus.

Dissociated Vertical Nystagmus (DVD) - More accurately a strabismus

Dissociated Vertical Deviation (DVD) is technically a form of strabismus rather than true nystagmus, though it involves alternating eye movements. It is characterized by an upward and outward (excyclotorsional) drift of one eye when it is covered or when attention is diverted, with the other eye maintaining fixation. When the cover is removed or attention returns, the deviated eye moves back down and inward. This can alternate between the eyes. DVD often indicates dysfunction in the supranuclear pathways controlling vertical eye alignment, possibly involving the nuclei of the reticular formation of the midbrain, including the interstitial nucleus of Cajal (INC). DVD can occur with congenital strabismus, tumors located over the area of the sella turcica (e.g., craniopharyngioma), head trauma, and less often with cerebral infarctions. It is frequently associated with latent nystagmus or infantile esotropia and may sometimes be linked with visual field defects like bitemporal hemianopsia if chiasmal compression is present.

Conditions Resembling Nystagmus (Saccadic Intrusions and Oscillations)

True nystagmus can be mimicked by other types of abnormal eye movements, often referred to as saccadic intrusions or oscillations. These are typically rapid, unwanted saccades that interrupt steady fixation, rather than the rhythmic slow/fast phases of jerk nystagmus or the sinusoidal waves of pendular nystagmus. Examples include:

- Square Wave Jerks/Square Wave Oscillations: Small, conjugate, horizontal jerky movements that take the eyes off target and then, after a brief pause, a corrective saccade brings them back. These have a characteristic rectangular signal on eye movement recordings. Occasional square wave jerks can be normal, but frequent or large ones can be pathological (e.g., cerebellar disease, progressive supranuclear palsy).

- Macrosaccadic Oscillations: Large, hypermetric saccades that overshoot the target, followed by a series of smaller corrective saccades back to the target. Often seen with cerebellar disease.

- Ocular Flutter: Bursts of rapid, conjugate, horizontal back-to-back saccades without an intersaccadic interval, occurring around the point of fixation.

- Opsoclonus ("Saccadomania"): Characterized by frequent, multidirectional (horizontal, vertical, torsional), conjugate, chaotic, high-frequency saccadic oscillations that are continuous and occur even with eyes closed. Often associated with paraneoplastic syndromes (especially neuroblastoma in children), viral encephalitis, or metabolic encephalopathies.

- Superior Oblique Myokymia: A rare condition causing monocular, intermittent, high-frequency, low-amplitude torsional-vertical shimmering or trembling movements of one eye, often perceived by the patient as oscillopsia or diplopia.

- Ocular Bobbing: A non-rhythmic, rapid downward deviation of both eyeballs with a slow return to the primary position. Typically seen in comatose patients with severe pontine lesions. Variants include ocular dipping (slow down, fast up) and reverse bobbing.

- Periodic Alternating Gaze Deviation: Slow, periodic, conjugate horizontal movements of the eyeballs, with the direction of deviation changing every few seconds. Can be seen in comatose patients or those with cerebellar or brainstem lesions.

Diagnosis of Nystagmus

The diagnostic approach to nystagmus aims to characterize the eye movements and identify the underlying cause.

Clinical Examination

A thorough neurological and neuro-ophthalmological examination is key:

- Observation: Noting the presence of nystagmus in primary gaze and in all nine diagnostic positions of gaze. Characterizing its type (pendular, jerk), direction, amplitude, frequency, and whether it is conjugate or dissociated. Observing for a null point or abnormal head posture.

- Visual Acuity and Refraction.

- Pupil Examination.

- Fundoscopy: To assess the optic nerves and retina.

- Tests for Vestibular Function: Head impulse test, Dix-Hallpike maneuver (for BPPV), caloric testing, rotational chair testing.

- Assessment of Smooth Pursuit and Saccades.

- Cover Test: To detect strabismus, which can be associated with or mimic some forms of nystagmus (like DVD).

Detailed anamnesis about onset (congenital vs. acquired), duration, associated symptoms (vertigo, oscillopsia, hearing loss, neurological deficits), medications, alcohol use, and family history is crucial.

Further Investigations

- Eye Movement Recordings (e.g., Electronystagmography - ENG, Videonystagmography - VNG): Provide objective quantification and characterization of nystagmus.

- Imaging:

- MRI of the Brain and Brainstem: Essential for evaluating suspected central causes (e.g., stroke, tumor, multiple sclerosis, cerebellar lesions, Chiari malformation).

- CT Scan of Temporal Bones: If inner ear pathology is suspected.

- Laboratory Tests: Blood tests for metabolic disorders, vitamin deficiencies (e.g., thiamine), infections, or autoimmune conditions, depending on clinical suspicion.

- Genetic Testing: For suspected hereditary forms of nystagmus or associated syndromes.

General Principles of Nystagmus Management

Treatment for nystagmus is highly dependent on the underlying cause and aims to improve vision, reduce oscillopsia, and address the primary pathology.

- Treating the Underlying Cause: This is the most important aspect (e.g., treating an inner ear infection, discontinuing an offending medication, managing multiple sclerosis, removing a tumor).

- Optical Correction: Eyeglasses or contact lenses to correct refractive errors can sometimes improve visual acuity and reduce nystagmus. Prisms may be used in some cases to shift the null point or reduce diplopia.

- Medications:

- For some types of acquired nystagmus, medications like gabapentin, memantine, baclofen (especially for PAN), or 4-aminopyridine may provide symptomatic relief.

- Drugs to treat vertigo may be used for vestibular nystagmus.

- Botulinum Toxin Injections: Can be used to weaken specific extraocular muscles in some forms of nystagmus or strabismus, but effects are temporary.

- Surgical Procedures:

- Strabismus surgery (e.g., Kestenbaum-Anderson procedure) can be performed in some cases of congenital nystagmus to shift the null point to primary gaze, improving abnormal head posture and visual function.

- Surgery to address the underlying cause (e.g., tumor removal).

- Vision Therapy/Rehabilitation: Exercises and strategies to improve visual function and adapt to nystagmus.

- Low Vision Aids: If visual acuity is significantly impaired.

Differential Diagnosis of Nystagmus by Type/Cause

Differentiating the cause of nystagmus requires careful clinical correlation:

| Type of Nystagmus | Common Associated Causes/Conditions |

|---|---|

| Congenital Nystagmus (Infantile Nystagmus Syndrome) | Idiopathic, albinism, optic nerve hypoplasia, congenital cataracts, aniridia, Leber's congenital amaurosis. |

| Peripheral Vestibular Nystagmus (Horizontal-Torsional, Jerk) | Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), Vestibular neuritis, Labyrinthitis, Meniere's disease, Vestibular schwannoma (early), Aminoglycoside toxicity. |

| Central Vestibular Nystagmus (Pure Vertical, Pure Torsional, Gaze-Evoked) | Brainstem or cerebellar stroke, Multiple sclerosis, Tumors (posterior fossa), Chiari malformation, Wernicke's encephalopathy, Drug intoxication (e.g., anticonvulsants, sedatives, lithium). |

| Downbeat Nystagmus | Cerebellar degeneration/atrophy, Chiari malformation, Multiple sclerosis, Brainstem lesions, Drug toxicity (lithium, anticonvulsants). |

| Upbeat Nystagmus | Lesions of anterior cerebellar vermis, Brainstem lesions (medulla, pons), Wernicke's encephalopathy, Multiple sclerosis. |

| Gaze-Evoked Nystagmus | Drug intoxication (sedatives, anticonvulsants, alcohol), Cerebellar disease, Brainstem lesions affecting neural integrator. |

| Periodic Alternating Nystagmus (PAN) | Cerebellar disease (especially nodulus/uvula), Chiari malformation, Multiple sclerosis, Anticonvulsant toxicity, Congenital. |

| Convergence-Retraction Nystagmus | Dorsal midbrain syndrome (Parinaud's syndrome) due to pineal tumor, hydrocephalus, stroke, MS. |

Importance of Neurological and Neuro-Ophthalmological Evaluation

Visual impairments and abnormal eyeball movements are critical signals of potential underlying danger or significant pathology. The recognition and differentiation of these signs by a neurologist, neurosurgeon, or neuro-ophthalmologist are paramount. A clinician who is vigilant about such visible signals that the eye can send will not only be able to recognize and distinguish them from each other (e.g., true nystagmus vs. saccadic intrusions) but will also understand their crucial clinical significance in localizing lesions within the complex oculomotor and vestibular systems, guiding further investigation and appropriate management.

References

- Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The Neurology of Eye Movements. 5th ed. Oxford University Press; 2015.

- Brazis PW, Masdeu JC, Biller J. Localization in Clinical Neurology. 7th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016. Chapter 10: Nystagmus and Saccadic Intrusions.

- Serra A, Leigh RJ. Diagnostic approach to nystagmus. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002 Feb;15(1):21-32.

- Dell'Osso LF, Daroff RB. Nystagmus and Saccadic Intrusions and Oscillations. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2019:chap 9.12.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC), Section 5: Neuro-Ophthalmology. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology. (Published annually).

- Strupp M, Kremmyda O, Adamczyk C, et al. Central ocular motor disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014 Feb;27(1):92-9.

- Tusa RJ, Shaikh AG. Nystagmus. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019 Aug;25(4):1065-1085.

- Abel LA. Infantile nystagmus: current concepts in diagnosis and management. Strabismus. 2006 Jun;14(2):67-73.

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Spinal disc herniation

- Pain in the arm and neck (trauma, cervical radiculopathy)

- The eyeball and the visual pathway:

- Anatomy of the eye and physiology of vision

- The visual pathway and its disorders

- Eye structures and visual disturbances that occur when they are affected

- Retina and optic disc, visual impairment when they are affected

- Impaired movement of the eyeballs

- Nystagmus and conditions resembling nystagmus

- Dry Eye Syndrome

- Optic nerve and retina:

- Compression neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Edema of the optic disc (papilledema)

- Ischemic neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Meningioma of the optic nerve sheath

- Optic nerve atrophy

- Optic neuritis in adults

- Optic neuritis in children

- Opto-chiasmal arachnoiditis

- Pseudo-edema of the optic disc (pseudopapilledema)

- Toxic and nutritional optic neuropathy

- Neuropathies and neuralgia:

- Diabetic, alcoholic, toxic and small fiber sensory neuropathy (SFSN)

- Facial nerve neuritis (Bell's palsy, post-traumatic neuropathy)

- Fibular (peroneal) nerve neuropathy

- Median nerve neuropathy

- Neuralgia (intercostal, occipital, facial, glossopharyngeal, trigeminal, metatarsal)

- Post-traumatic neuropathies

- Post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy

- Post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy

- Radial nerve neuropathy

- Tibial nerve neuropathy

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Ulnar nerve neuropathy

- Tumors (neoplasms) of the peripheral nerves and autonomic nervous system (neuroma, sarcomatosis, melanoma, neurofibromatosis, Recklinghausen's disease)

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Ulnar nerve compression in the cubital canal