Post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy

- Understanding Post-Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Neuropathy

- Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Sciatic Nerve Injury

- Diagnosis of Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Neuropathy

- Treatment of Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Neuropathy (Sciatica)

- Differential Diagnosis of Leg Pain, Weakness, and Sensory Loss

- Prognosis and Potential Complications

- Prevention of Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Injury

- When to Consult a Neurologist or Neurosurgeon

- References

Understanding Post-Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Neuropathy

Post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy refers to damage or dysfunction of the sciatic nerve (nervus ischiadicus) resulting directly from physical injury. The sciatic nerve is the largest and longest nerve in the human body, and injuries to it can lead to significant motor and sensory deficits in the lower extremity.

Anatomy and Function of the Sciatic Nerve

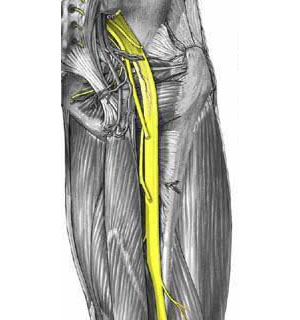

The sciatic nerve is a mixed nerve, meaning it carries both motor fibers (responsible for movement) and sensory fibers (responsible for sensation). It is formed from the ventral rami of the spinal nerves L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3, originating from the lumbosacral plexus within the pelvis. It exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, typically inferior to the piriformis muscle, and descends along the posterior aspect of the thigh.

In the upper part of the popliteal fossa (behind the knee), or sometimes higher in the thigh, the sciatic nerve typically divides into its two main terminal branches:

- Tibial Nerve: Continues down the posterior compartment of the leg, innervating the plantar flexor muscles of the ankle and foot, toe flexors, and providing sensation to the sole of the foot.

- Common Peroneal (Fibular) Nerve: Winds laterally around the neck of the fibula and divides into superficial and deep peroneal nerves, which innervate the dorsiflexors and evertors of the foot, toe extensors, and provide sensation to the anterolateral leg and dorsum of the foot.

Even before its formal division, the peroneal and tibial portions of the sciatic nerve are usually distinctly isolated within a common epineural sheath (subepineural isolation) as high as the pelvic cavity.

The sciatic nerve itself, proximal to its main division, innervates the hamstring muscles (semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris long head), which are responsible for knee flexion, and the adductor magnus (partially).

Common Causes of Traumatic Sciatic Neuropathy

Traumatic injuries to the sciatic nerve can occur through various mechanisms:

- Hip Dislocation or Fracture-Dislocation: Posterior hip dislocations are particularly notorious for causing sciatic nerve injury due to stretching or direct contusion by the displaced femoral head.

- Femur Fractures: Especially fractures of the femoral shaft or supracondylar region.

- Pelvic Fractures.

- Penetrating Injuries: Gunshot wounds, stab wounds to the buttock or posterior thigh.

- Iatrogenic Injury:

- During hip replacement surgery (total hip arthroplasty).

- Intramuscular injections improperly administered into the buttock (direct needle trauma or intraneural injection).

- Surgical procedures in the gluteal region or posterior thigh.

- Prolonged compression during surgery due to improper positioning.

- Blunt Trauma or Crush Injuries: To the buttock or posterior thigh.

- Compartment Syndrome: In the thigh or gluteal region (rare).

Injuries to such a large nerve as the sciatic nerve are rarely completely transecting unless due to severe penetrating trauma. More often, the injury is partial, or one portion of the sciatic nerve (e.g., the peroneal division, which is often more vulnerable) suffers more damage than the other (tibial division).

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Sciatic Nerve Injury

The clinical manifestations of traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy depend on the level and severity of the nerve lesion.

Impact of Lesion Level

Only a very high lesion of the sciatic nerve, typically above the gluteal fold (in the buttock or pelvis), will result in loss of function of the hamstring muscles (which the sciatic nerve innervates directly in the thigh), leading to an inability or severe weakness in flexing the lower leg at the knee. Such high lesions are often accompanied by simultaneous damage to the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh, causing sensory loss over the posterior aspect of the thigh.

With a complete sciatic nerve lesion at any level proximal to its main bifurcation, the functions of both its major branches – the tibial and peroneal nerves – will suffer. This results in a comprehensive symptom complex characterized by:

- Complete paralysis of all muscles below the knee: Leading to a flail foot (inability to move the foot or toes). This includes foot drop (loss of dorsiflexion and eversion due to peroneal nerve dysfunction) and loss of plantarflexion and inversion (due to tibial nerve dysfunction).

- Loss of the Achilles tendon reflex (mediated by the tibial nerve, S1-S2).

- Anesthesia (loss of sensation): Affecting almost the entire leg below the knee and the foot, except for a strip of skin along the medial leg and medial malleolus supplied by the saphenous nerve (a branch of the femoral nerve).

Pain and Lasegue's Sign

Sciatic nerve lesions, particularly those involving irritation or inflammation (often termed "sciatica" or traumatic neuritis), can be accompanied by severe pain, which may be burning, shooting, or aching in character, typically radiating down the posterior thigh, leg, and into the foot along the nerve's distribution.

Irritation and inflammation of the sciatic nerve often give rise to a characteristic positive **Lasegue's sign** (Straight Leg Raise test):

- Phase 1: If a patient with sciatica is lying supine, and the examiner passively flexes the hip by lifting the leg while keeping the knee straight, pain occurs along the posterior surface of the leg (described as "pulling the leg"). This pain is due to stretching of the irritated sciatic nerve, which is located along the back of the thigh and lower leg.

- Phase 2: If, after eliciting pain in Phase 1, the leg is then bent at the knee joint (while maintaining hip flexion), the tension on the sciatic nerve is relieved. Further flexion at the hip joint can then occur painlessly. This confirms the sciatic nerve as the source of pain.

Variations of this test, such as the Bragard sign (dorsiflexion of the foot during straight leg raise exacerbates pain) or a crossed straight leg raise sign (raising the unaffected leg elicits pain in the affected leg, often indicative of a large disc herniation), can provide further diagnostic clues, though these are more typical for radicular compression than direct traumatic neuropathy.

Video illustrating anatomical course and common issues related to the sciatic nerve.

Diagnosis of Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Neuropathy

Diagnosing traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy involves a careful clinical assessment, electrodiagnostic studies, and often imaging to determine the location, extent, and nature of the injury.

Clinical Examination

- History: Detailed account of the trauma (mechanism, timing, severity), onset and progression of symptoms (pain, weakness, sensory loss).

- Motor Examination: Assessment of muscle strength in hip extensors (gluteus maximus - partially sciatic), knee flexors (hamstrings), and all muscle groups below the knee (ankle dorsiflexors, plantarflexors, invertors, evertors; toe extensors and flexors).

- Sensory Examination: Testing for light touch, pinprick, temperature, vibration, and proprioception in the distribution of the sciatic nerve and its branches (posterior thigh, entire leg below the knee except medial aspect, sole and dorsum of foot).

- Reflex Examination: Achilles reflex (S1-S2, tibial nerve) is typically absent or diminished with sciatic nerve lesions affecting tibial division. Patellar reflex (L2-L4, femoral nerve) should be normal.

- Special Tests: Lasegue's sign (Straight Leg Raise test).

- Observation of Gait: Looking for foot drop, steppage gait, or inability to bear weight.

- Palpation: For tenderness along the nerve course or at the site of injury.

Electrodiagnostic Studies (EMG/NCS)

Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS/ENG) are crucial for:

- Confirming sciatic neuropathy and localizing the lesion site (e.g., distinguishing from lumbosacral radiculopathy or plexopathy).

- Determining if the peroneal or tibial division is more severely affected.

- Assessing the severity of axonal loss versus demyelination (conduction block).

- Providing prognostic information about the potential for recovery.

- Monitoring for signs of reinnervation over time.

These studies are usually performed 2-4 weeks after injury to allow for Wallerian degeneration to occur if axons are damaged.

Imaging Studies

- X-rays: Of the pelvis, hip, and femur to identify fractures or dislocations that may have caused the nerve injury.

- CT Scan: Can provide more detailed information about bony injuries.

- MRI: The preferred imaging modality for visualizing the sciatic nerve itself, surrounding soft tissues, and identifying potential causes of compression or injury such as hematomas, tumors, scar tissue, or direct nerve trauma. MRI of the lumbosacral spine may be needed to rule out radiculopathy.

- Ultrasound: High-resolution ultrasound can sometimes visualize the nerve and detect focal lesions or entrapment, particularly in more superficial segments.

Treatment of Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Neuropathy (Sciatica)

The treatment of post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy (often presenting with sciatica, which refers to pain radiating along the sciatic nerve) must be individualized, taking into account the level and severity of nerve damage, the extent of motor and sensory deficits, and the stage of the injury (acute vs. chronic). Different stages of sciatic nerve neuropathy may require different therapeutic approaches. It should be remembered that long-standing, severe neuropathy of the sciatic nerve can aggravate the further prognosis for the restoration of its lost functions due to factors like muscle atrophy and joint contractures.

General Principles and Conservative Management

- Addressing the Cause: If ongoing compression or irritation is present (e.g., from a hematoma, displaced bone fragment), this needs to be addressed.

- Pain Management:

- NSAIDs for inflammatory pain.

- Neuropathic pain medications (gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants, SNRIs) for nerve-related pain.

- Opioids may be needed for severe acute pain but are generally avoided for chronic use.

- Immobilization/Support:

- Ankle-Foot Orthosis (AFO) for foot drop to improve gait and prevent tripping.

- Splinting to prevent contractures.

- Protection of Anesthetic Areas: Care to prevent skin breakdown or injury in areas with sensory loss.

Pharmacological Treatment

As mentioned, pain control is key. Additionally:

- Vitamins: B-complex vitamins (B1, B6, B12), Vitamin C, and Vitamin E are often prescribed as neurotrophic support, though evidence for significant nerve regeneration in traumatic neuropathy is limited.

- Corticosteroids: A short course of oral corticosteroids may be considered in the acute phase of some traumatic or inflammatory neuropathies to reduce swelling and inflammation around the nerve, but their role in direct traumatic sciatic neuropathy is not well-established.

Rehabilitative Therapies

Post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy (sciatica) is treated by individually tailoring a comprehensive rehabilitation program for each patient. This often includes a set of the following conservative procedures:

- Physical Therapy: Essential for maintaining range of motion, preventing contractures, strengthening remaining innervated muscles, and later, re-educating weakened muscles as reinnervation occurs. Gait training with an AFO if needed.

- Occupational Therapy: To adapt daily activities.

- Acupuncture: May help with pain management and potentially promote nerve recovery in some individuals.

- Neurostimulation of the sciatic nerve and leg muscles: Techniques like TENS for pain, or EMS/FES to maintain muscle viability or assist with function.

- Homeopathic Remedies: Some patients explore these, but scientific evidence for efficacy in nerve regeneration is generally lacking.

Surgical Intervention

Surgical exploration and intervention may be indicated in specific circumstances:

- Open Injuries: Lacerations or penetrating trauma with suspected nerve transection often require early surgical exploration and repair (neurorrhaphy).

- Known Compressive Lesions: E.g., hematoma, tumor, displaced bone fragment causing ongoing nerve compression.

- Failure of Spontaneous Recovery: If there are no clinical or electrophysiological signs of recovery after an appropriate observation period (e.g., 3-6 months for closed injuries), especially with severe axonal loss.

- Progressive Neurological Deficit.

Surgical procedures include:

- Neurolysis: Freeing the nerve from scar tissue or external compression. This can be external (around the nerve) or internal (within the nerve fascicles, more complex).

- Nerve Repair (Neurorrhaphy): Direct suturing of cleanly transected nerve ends.

- Nerve Grafting: If there is a gap between nerve ends that cannot be repaired directly, a segment of another nerve (e.g., sural nerve) is used as a graft to bridge the defect.

- Nerve Transfers: In some cases, a healthy nearby nerve or one of its branches can be transferred to reinnervate the denervated muscles.

- Tendon Transfers or Arthrodesis: Secondary reconstructive procedures for permanent paralysis to improve function or stabilize joints.

Differential Diagnosis of Leg Pain, Weakness, and Sensory Loss

Symptoms of sciatic neuropathy must be differentiated from other conditions affecting the lower limb:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Post-Traumatic Sciatic Neuropathy | Clear history of significant trauma to buttock, hip, or thigh; deficits correspond to sciatic nerve distribution (hamstrings, all muscles below knee, sensation posterior thigh/leg/foot). Achilles reflex often lost. |

| Lumbosacral Radiculopathy (e.g., L5, S1) | Often associated with back pain, disc herniation, or spinal stenosis. Pain follows dermatomal pattern. Weakness specific to myotomes (e.g., L5: foot/toe dorsiflexion, hip abduction; S1: plantarflexion, eversion). Reflex changes specific to root level. Positive straight leg raise. |

| Peroneal Neuropathy (at Fibular Head) | Isolated foot drop (weak dorsiflexion/eversion), sensory loss over anterolateral leg/foot dorsum. Plantarflexion and inversion normal. Achilles reflex normal. Often history of compression at fibular head. |

| Tibial Neuropathy (in Popliteal Fossa or Tarsal Tunnel) | Weakness of plantarflexion/inversion, toe flexion. Sensory loss on sole of foot. Achilles reflex lost. |

| Lumbosacral Plexopathy | More widespread, often asymmetrical weakness and sensory loss in multiple lumbosacral nerve distributions. Causes include trauma, tumor, inflammation, diabetes, radiation. |

| Piriformis Syndrome | Pain in buttock radiating down leg, mimicking sciatica. Thought to be due to sciatic nerve compression by piriformis muscle. Diagnosis often clinical, somewhat controversial. |

| Peripheral Polyneuropathy | Usually symmetrical, distal "stocking-glove" sensory loss, weakness, and reflex changes. Multiple potential causes (diabetes, alcohol, toxins, etc.). |

| Vascular Claudication | Leg pain (cramping) induced by exercise, relieved by rest. Due to arterial insufficiency. Peripheral pulses may be diminished/absent. No primary neurological deficits. |

Prognosis and Potential Complications

The prognosis for recovery after traumatic sciatic nerve injury is highly variable and depends on:

- Severity of Injury: Neurapraxia (conduction block) has the best prognosis, often with full recovery. Axonotmesis (axonal damage with intact nerve sheath) allows for regeneration but recovery may be slow and incomplete. Neurotmesis (complete nerve transection or severe disruption) has the poorest prognosis without surgical repair.

- Level of Injury: More proximal injuries have a longer distance for axons to regenerate, leading to slower and potentially less complete recovery.

- Type of Trauma: Sharp transections repaired early have a better prognosis than crush or stretch injuries.

- Age and Overall Health of the Patient.

- Timeliness and Appropriateness of Treatment.

Potential long-term complications include:

- Persistent motor weakness (e.g., foot drop, weak knee flexion).

- Chronic neuropathic pain.

- Permanent sensory loss.

- Muscle atrophy.

- Joint contractures and deformities.

- Impaired gait and mobility.

- Development of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

Prevention of Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Injury

While not all traumatic injuries are preventable, some measures can reduce risk:

- Adherence to safety protocols in sports and occupational settings.

- Careful surgical technique during procedures near the sciatic nerve (e.g., hip arthroplasty, injections). Correct landmarking for intramuscular injections in the buttock is crucial.

- Awareness of vulnerable positions that can compress the nerve during prolonged immobility or anesthesia.

When to Consult a Neurologist or Neurosurgeon

Following significant trauma to the pelvis, hip, or thigh, immediate medical evaluation is necessary. Consultation with a neurologist or neurosurgeon specializing in peripheral nerve injuries should be sought if:

- There are signs of sciatic nerve dysfunction (weakness in leg/foot, sensory loss, severe radiating pain) after trauma.

- An open injury with potential nerve laceration has occurred.

- There is no improvement or worsening of neurological deficits after an initial period of observation for closed injuries.

- Electrodiagnostic studies suggest severe axonal loss or complete denervation with no signs of recovery.

- A compressive lesion (e.g., hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, retained foreign body) is identified on imaging.

Early and accurate diagnosis, along with timely intervention when indicated, are key to maximizing the potential for recovery from traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy.

References

- Beasley G, Karsy M, Kunnathia J, et al. Traumatic Sciatic Nerve Injury: A Review for the Modern Era. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2021;163(3):631-640.

- Stewart JD. Focal Peripheral Neuropathies. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. Chapter 14: Sciatic Neuropathy.

- Kline DG, Kim D, Midha R, Olshansky K, Tiel R. Management and results of sciatic nerve injuries: a 24-year experience. J Neurosurg. 2007 Jan;106(1):123-30.

- Seddon HJ. Three types of nerve injury. Brain. 1943;66(4):237-288. (Classical classification of nerve injuries)

- Spinner RJ, Kliot M. Surgery for Peripheral Nerve Lesions of the Lower Extremity. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(2):242-253.

- Preston DC, Shapiro BE. Electromyography and Neuromuscular Disorders: Clinical-Electrophysiologic Correlations. 3rd ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2013. Chapter 20: Sciatic Neuropathy.

- Dyck PJ, Thomas PK. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2005. (Comprehensive reference on peripheral nerve disorders)

- Campbell WW. DeJong's The Neurologic Examination. 8th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019.

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Spinal disc herniation

- Pain in the arm and neck (trauma, cervical radiculopathy)

- The eyeball and the visual pathway:

- Anatomy of the eye and physiology of vision

- The visual pathway and its disorders

- Eye structures and visual disturbances that occur when they are affected

- Retina and optic disc, visual impairment when they are affected

- Impaired movement of the eyeballs

- Nystagmus and conditions resembling nystagmus

- Dry Eye Syndrome

- Optic nerve and retina:

- Compression neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Edema of the optic disc (papilledema)

- Ischemic neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Meningioma of the optic nerve sheath

- Optic nerve atrophy

- Optic neuritis in adults

- Optic neuritis in children

- Opto-chiasmal arachnoiditis

- Pseudo-edema of the optic disc (pseudopapilledema)

- Toxic and nutritional optic neuropathy

- Neuropathies and neuralgia:

- Diabetic, alcoholic, toxic and small fiber sensory neuropathy (SFSN)

- Facial nerve neuritis (Bell's palsy, post-traumatic neuropathy)

- Fibular (peroneal) nerve neuropathy

- Median nerve neuropathy

- Neuralgia (intercostal, occipital, facial, glossopharyngeal, trigeminal, metatarsal)

- Post-traumatic neuropathies

- Post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy

- Post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy

- Radial nerve neuropathy

- Tibial nerve neuropathy

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Ulnar nerve neuropathy

- Tumors (neoplasms) of the peripheral nerves and autonomic nervous system (neuroma, sarcomatosis, melanoma, neurofibromatosis, Recklinghausen's disease)

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Ulnar nerve compression in the cubital canal