Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Understanding Pain in the Neck, Head, and Arm (cervical degenerative disc disease Context)

- Common Causes and Contributing Factors

- Degeneration of Discs and Vertebrae (cervical degenerative disc disease/Spondylosis)

- Improper Sleeping Position

- Poor Posture and Slouching

- Stress and Anxiety

- Acute Torticollis (Wry Neck)

- Brachial Plexus Injury

- Whiplash Injury of the Neck (Cervico-Cranial Syndrome)

- Cervical Radiculopathy ("Pinched Nerve")

- Diagnostic Pitfalls and Importance of Clinical Examination

- Common Causes and Contributing Factors

- Diagnosis of Pain in the Neck, Head, and Arm

- Treatment of Pain in the Neck, Head, and Arm

- Symptoms of Cervical Spine Degenerative Disc Disease Exacerbation

- Differential Diagnosis of Neck, Head, and Arm Pain

- Prevention and Lifestyle Adjustments

- When to Consult a Specialist

- References

Understanding Pain in the Neck, Head, and Arm (cervical degenerative disc disease Context)

Pain in the neck (cervicalgia), often radiating to the back of the head (occiput), temples, forehead, or down the arm, is a very common problem faced by many individuals throughout their lives. While various conditions can cause these symptoms, myofascial pain (pain originating from muscles and their surrounding connective tissue) is frequently implicated, often in the context of degenerative changes in the cervical spine, commonly referred to as cervical degenerative disc disease or spondylosis.

The neck muscles, including the trapezius, levator scapulae, and scalene muscles, are not only responsible for moving the neck and supporting the head but also play an active role during arm movements. This interconnectedness means that issues in the neck can easily refer pain or cause symptoms in adjacent regions.

A widespread scenario is the acute onset of neck pain, often experienced in the morning after sleeping in an awkward or uncomfortable position, or following a sudden, unguarded movement of the head. Such pain is frequently muscular in origin and can radiate to various areas: the back of the head, forehead, eye, ear, or shoulder. It may be described as a pulling sensation or a burning feeling in the area of the scapula (shoulder blade) or beneath it. Unfortunately, diagnostic errors can occur by both patients self-diagnosing and sometimes by attending physicians if a thorough clinical biomechanical assessment is overlooked in favor of relying solely on imaging findings.

Common Causes and Contributing Factors

Pain in the neck, head, and arm can be provoked by a variety of factors, often interrelated:

Degeneration of Discs and Vertebrae (cervical degenerative disc disease/Spondylosis)

Daily mechanical stress and the natural aging process can lead to wear and tear (degeneration) of the cervical intervertebral discs and vertebrae. This process, often termed cervical degenerative disc disease or spondylosis, can result in chronic or recurrent neck pain. Some individuals experience faster or more pronounced degenerative changes due to their type of work (e.g., prolonged sitting, repetitive neck movements), lifestyle (e.g., lack of exercise, poor ergonomics), posture, and genetic predispositions. As we age, the intervertebral discs tend to lose height and hydration, which increases stress and wear on the facet joints (intervertebral joints). This can lead to narrowing of the spinal canal or intervertebral foramina (where nerve roots exit), potentially causing nerve damage or irritation. In many cases, pain resulting from these degenerative processes can be managed effectively with conservative treatments like physical therapy, without requiring surgery.

Improper Sleeping Position

The position in which one sleeps, the number and type of pillows used, and the firmness of the mattress can all significantly impact how the neck feels upon waking. An incorrect or unsupportive sleeping position is a primary cause of morning neck pain and stiffness. While often overlooked, sleep ergonomics play a crucial role in neck health. For example, a worn-out or inappropriately sized pillow can keep the neck tilted at an unnatural angle for an extended period, leading to muscle tension, ligamentous strain, and pain. Patients with neck pain are often advised to sleep on their side or back with a pillow that maintains the neck in a neutral alignment with the rest of the spine. This usually helps to alleviate or prevent morning neck pain.

Poor Posture and Slouching

In many instances, neck pain is a direct consequence of poor posture maintained during daily activities such as sitting (especially at a computer), walking, or even standing. The now ubiquitous use of smartphones and tablets ("text neck"), and prolonged sitting in front of a low computer screen, contribute significantly to postural strain. Poor posture, characterized by a forward head position and rounded shoulders, places excessive stress on the muscles, ligaments, and joints of the cervical spine. This can aggravate pre-existing complaints and symptoms or lead to new ones. Patients with poor posture often experience pulling pain in the neck muscles and between the shoulder blades, frequently described as a burning sensation at the base of the neck. The most effective way to address this type of pain is to actively work on improving posture through awareness, ergonomic adjustments, and specific exercises. More serious consequences of chronic poor posture can include weakness in the arms and legs or numbness and tingling in the hands, and even decreased manual dexterity, if nerve compression develops.

Stress and Anxiety

Daily psychological stress and anxiety can lead to involuntary and sustained muscle contraction (tension) in the shoulders and neck. This chronic muscle over-straining can directly result in pain. Furthermore, psychological factors have a significant impact on how individuals perceive pain; stressful situations can heighten pain perception and reduce pain tolerance. While it may be easier said than done, stress management techniques are extremely important in relieving stress-related neck pain. Strategies such as increasing physical activity, mindfulness, relaxation exercises, or seeking professional counseling can be very helpful in coping with stress and reducing its physical manifestations.

Acute Torticollis (Wry Neck)

Acute torticollis, or wry neck, is a condition characterized by a painfully tilted or twisted neck, where the head is involuntarily turned to one side. Attempts to straighten the head from this position are usually accompanied by significant pain and muscle spasm. Although the exact cause of acute torticollis is not always known (idiopathic), it is often suspected to be caused by minor sprains of cervical ligaments or acute muscle strains. Exposure of the neck to cold temperatures (e.g., sleeping near a draft) for an extended period can also be a trigger. This muscle tension and abnormal head position cause pain and can also put the cervical nerve roots under tension, potentially leading to irritation or radicular symptoms. Acute torticollis is a relatively common condition in the general population.

Brachial Plexus Injury

The brachial plexus is a complex network of nerves originating from the cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord (C5-T1 nerve roots) that provides motor and sensory innervation to the shoulder, arm, and hand. If these nerves are stretched, compressed, or damaged (brachial plexopathy), it can cause neck pain, often radiating into the arm. Conversely, a neck injury (e.g., trauma, severe disc herniation) that affects the brachial plexus or its contributing nerve roots can also result in arm pain. Brachial plexus injury manifests with a variety of motor (weakness, paralysis) and sensory (numbness, tingling, pain) disorders in the upper limb. Minor "stinger" or "burner" type injuries to the brachial plexus, often seen in contact sports or resulting from falls or traffic accidents, can heal quickly. In most such cases, the plexus injury involves stretching and may resolve on its own. However, more severe injuries, such as complete nerve root avulsions or plexus rupture, require specialized evaluation and may necessitate reconstructive surgery of the brachial plexus.

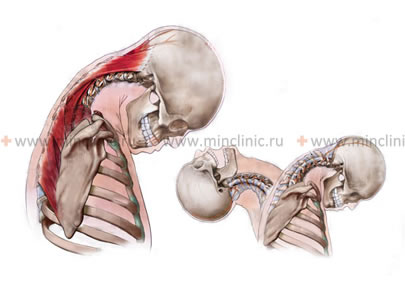

Whiplash Injury of the Neck (Cervico-Cranial Syndrome)

A whiplash injury to the neck occurs when the head is subjected to a sudden, forceful acceleration-deceleration movement, typically in an anteroposterior direction (hyperflexion-hyperextension), and then rapidly returns. This commonly happens in rear-end motor vehicle accidents but can also result from sports injuries or falls. The sharp jolt can lead to sprain/strain injuries of the muscles and ligaments in the neck (whiplash-associated disorder - WAD). In many cases, recovery from a mild whiplash injury occurs spontaneously over time with conservative management. Manipulative therapy of the neck, performed by a qualified practitioner, may help restore mobility and relieve pain in damaged tissues for some individuals. Severe whiplash injuries, however, can result in fractures of the cervical spine, disc herniations, or damage to the spinal cord and nerves. If neck pain continues to worsen following an accident or sports injury, or if neurological symptoms develop, it is recommended to seek prompt evaluation by a spine specialist.

The whiplash mechanism, often involving a sharp nod or jerking of the head during events like a car accident or collisions in sports (skating, rollerblading, skiing, snowboarding), can injure the ligaments and muscles of the neck, resulting in neck pain, occipital headache, and dizziness (cervico-cranial syndrome).

Cervical Radiculopathy ("Pinched Nerve")

Cervical radiculopathy occurs when a nerve root exiting the cervical spinal cord becomes compressed or irritated ("pinched"). This damage can cause pain that radiates from the neck down the arm along the distribution of the affected nerve root. The nerve roots can be pinched as they travel down the spinal canal or as they exit through the intervertebral foramina (bony openings between vertebrae). Common causes of cervical radiculopathy include:

- Herniated intervertebral disc pressing on a nerve root.

- Cervical spondylosis with osteophyte (bone spur) formation narrowing the neural foramina.

- Thickening of ligaments within the spinal canal (e.g., ligamentum flavum hypertrophy).

- Displaced (subluxated) vertebrae.

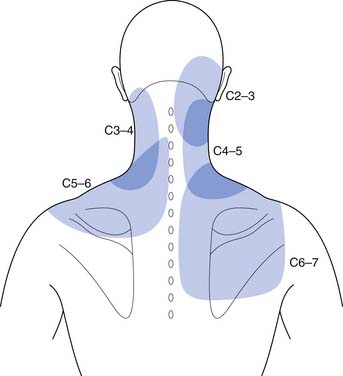

Cervical radiculopathy typically manifests as sharp, shooting, or "electric shock-like" pain radiating into the arm, shoulder, scapula, occipital region, or temple. Numbness, tingling (paresthesia), or muscle weakness in the arm or hand corresponding to the affected nerve root are also common. The specific location of these symptoms helps the doctor determine which cervical nerve root is involved (e.g., C5, C6, C7, or C8 radiculopathy).

When a cervical nerve root is compressed by a herniated intervertebral disc at the cervical level of the spine, the patient often experiences a sensation of pain, similar to an electric shock, radiating down the arm from the shoulder to the fingers.

The symptom of neck pain with a sprain of the ligaments of the cervical spine is often comparable to a boring, persistent toothache. When the neck hurts due to injury to ligaments and muscles, the patient often cannot find a comfortable sleeping position and finds it difficult to turn their head. Without specialized medical assistance, pain in the neck, back of the head, or head can last for several weeks without abating.

Muscular and radicular types of neck pain usually respond well to a combination of physiotherapy, cervical spine traction (e.g., using a Glisson loop, or manual traction during manual therapy sessions), and appropriate drug therapy (e.g., anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants).

Pain in the neck and occiput can also, rarely, be caused by spinal epiduritis (inflammation or infection of the epidural space), which can rapidly lead to the patient's spinal cord being compressed by infected epidural fat or an abscess, requiring urgent intervention.

Diagnostic Pitfalls and Importance of Clinical Examination

When a patient presents with acute muscular neck pain, they (or their physician) might prematurely proceed to hardware diagnostics such as X-rays of the cervical spine, Computed Tomography (CT), or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). While these imaging studies can be valuable in certain situations, their routine use for acute, uncomplicated muscular neck pain can lead to unnecessary financial costs and radiation exposure for the patient.

If natural age-related degenerative changes or common anatomical peculiarities (e.g., cervical degenerative disc disease, straightening of cervical lordosis, spondylosis, uncovertebral arthrosis, disc protrusion, or herniation) are found on these images, there can be a deviation from understanding the true underlying process causing the acute pain. Unfortunately, in the overwhelming majority of such cases, physicians might then overlook or skip further elementary diagnostics of the biomechanics of the cervical spine. Incidental changes found on imaging can become more significant in the clinical diagnosis than the actual clinical data obtained from a thorough physical examination (e.g., assessing the tone and strength of neck muscles, range of motion of the cervical spine, and identifying specific trigger points).

For acute, burning, or pulling muscular neck pain, the patient often just needs a comprehensive clinical examination by a specialist (e.g., neurologist, neurosurgeon, or physiatrist). Following such an examination in a specialized clinic, the patient typically:

- Receives an accurate clinical diagnosis based on physical findings.

- Avoids potentially unreasonable or unnecessary diagnostic methods and their associated financial and time costs.

- Avoids unnecessary radiation exposure.

- Receives adequate and targeted pain management.

- Receives recommendations for further treatment and rehabilitation after the acute pain symptom is relieved.

Diagnosis of Pain in the Neck, Head, and Arm (Context of cervical degenerative disc disease)

When a patient experiences persistent neck pain (whether posterior or lateral), and self-treatment measures like rubbing with ointments, applying heat, or taking over-the-counter painkillers do not provide relief, it is advisable to consult a doctor as soon as possible for a professional neurological and orthopedic examination. This is the only way to establish a correct diagnosis and reveal the true underlying cause of the neck pain.

Clinical Assessment

A thorough clinical assessment includes:

- Detailed History: Onset of pain (sudden vs. gradual), location, character (aching, burning, shooting), radiation patterns, aggravating and relieving factors, history of trauma or repetitive strain, occupational and recreational activities, sleep habits, and associated symptoms (numbness, tingling, weakness, dizziness, tinnitus).

- Physical Examination:

- Inspection for posture, head position, muscle asymmetry, or swelling.

- Palpation of neck muscles (trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, suboccipital muscles), spinous processes, and facet joints to identify areas of tenderness or trigger points.

- Assessment of active and passive range of motion of the cervical spine (flexion, extension, lateral bending, rotation) and noting any pain or limitation.

- Neurological examination to assess motor strength in the upper limbs, sensation in dermatomal patterns, deep tendon reflexes (biceps, triceps, brachioradialis), and provocative tests for radiculopathy (e.g., Spurling's maneuver, shoulder abduction relief test).

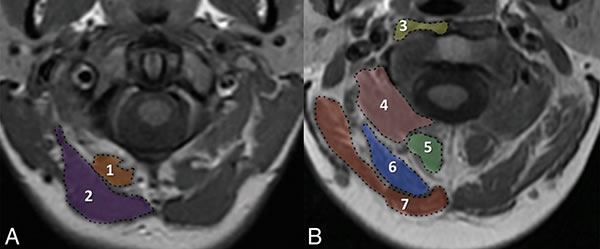

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the suboccipital (posterior neck) muscles. Muscles at the level of the anterior arch of the C1 vertebra (A): 1 - the small posterior rectus capitis muscle, 2 - the large posterior rectus capitis muscle. Muscles at the level of the middle of the odontoid process of the C2 vertebra (B): 3 - longus colli/capitis muscle, 4 - inferior oblique capitis muscle, 5 - semispinalis cervicis muscle, 6 - semispinalis capitis muscle, 7 - splenius capitis muscle. These muscles are often implicated in cervicogenic headaches and neck pain.

Imaging and Other Diagnostic Procedures

Based on the findings of the clinical consultation, if necessary, a patient presenting with symptoms of neck pain potentially related to cervical degenerative disc disease may be prescribed the following additional diagnostic procedures:

- Vascular Studies (REG, USDG): Rheoencephalography (REG) or Ultrasound Doppler Sonography (USDG) of the vessels of the neck (e.g., vertebral arteries, carotid arteries) and brain may be indicated if the patient experiences symptoms like dizziness, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), or unsteadiness when walking, to assess for vertebrobasilar insufficiency or other vascular compromise. cervical degenerative disc disease can lead to reflex spasm of the vertebral arteries, which run through foramina in the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae. This spasm, potentially due to pain and mechanical irritation from degenerative changes, can cause persistent disturbances in blood supply (ischemia) to the posterior parts of the brain, leading to such symptoms.

- X-ray of the Cervical Spine: Often performed with functional tests (flexion and extension views) to assess for degenerative changes (osteophytes, disc space narrowing, facet arthropathy), alignment (e.g., straightening or reversal of normal cervical lordosis), and instability.

- Computed Tomography (CT) of the Cervical Spine: Provides detailed bony anatomy, useful for evaluating complex fractures, severe spondylosis, or foraminal stenosis. CT myelography may be used if MRI is contraindicated.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Cervical Spine: The gold standard for visualizing soft tissues, including intervertebral discs (protrusions, herniations), the spinal cord (for myelopathy or other intrinsic lesions), nerve roots, and ligaments.

- Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS): May be used to confirm cervical radiculopathy or rule out peripheral neuropathy if arm symptoms are prominent.

On an MRI of the cervical spinal cord, myelopathy (spinal cord dysfunction) is visible, caused by a herniated disc at the C5-C6 level which is compressing the spinal cord from the front (indicated by the arrow).

In patients with cervical degenerative disc disease, pain in the posterior neck (back of the neck) is common, often accompanied by headaches in the occipital region. Sometimes this neck pain can simultaneously radiate (refer) to the arm, extending from the shoulder down to the hand, potentially with numbness of the fingers. Specifically, numbness in the hand affecting the little finger and ring finger can be associated with chronic overstrain of the scalene muscles or compression of the lower brachial plexus (thoracic outlet syndrome), a condition sometimes exacerbated by cervical spine issues.

Other serious causes for neck pain that need to be ruled out include:

- Injuries to the ligaments and muscles of the neck (cervico-cranial syndrome).

- Fracture of the bodies or arches of the cervical vertebrae.

- Tumors of the cervical vertebrae, spinal cord, or its membranes.

- Infections at the level of the neck, such as myelitis, epiduritis, or inflammation and enlargement of cervical lymph nodes.

- Significant damage to an intervertebral disc of the cervical spine, such as a large disc herniation, disc protrusion, or discitis (infection of the disc).

Understanding the intricate structure of the cervical spine is crucial for diagnosing sources of neck, head, and arm pain.

Degenerative diseases of the spine (such as cervical degenerative disc disease, osteoporosis of the cervical vertebrae, and osteoarthrosis of the intervertebral joints) affecting the neck typically occur due to the natural aging process of the spine. Repeated neck trauma can accelerate these degenerative processes in individuals with existing osteochondrosis, spondyloarthrosis, and spondylosis of the cervical spine.

Patients often complain of neck pain, numbness, and tingling extending down into the hands and fingers (which may worsen when lying on their back during sleep), and sometimes cracking, crunching, or clicking sounds in the cervical spine during movements like turning or tilting the head.

A lateral radiograph of the cervical spine can indicate changes in the normal cervical lordosis (inward curve), such as an excessively pronounced curve (hyperlordosis) or a smoothed, straightened curve (loss of lordosis), which can be associated with neck pain.

Symptoms of Cervical Spine Degenerative Disc Disease Exacerbation

An acute exacerbation of cervical degenerative disc disease can manifest with a variety of symptoms, including:

- Muscular pain in the neck, back of the head (occiput), shoulder, or radiating down the arm.

- A crunching or grinding sensation (crepitus) in the neck when turning or tilting the head to the sides.

- Burning pain or discomfort located between the shoulder blades (interscapular region).

- Limitation of neck mobility accompanied by an exacerbation of muscular pain.

- Neurological symptoms such as dizziness (vertigo), nausea, double vision (diplopia), numbness of the face or tongue, and general weakness, potentially indicative of vertebrobasilar insufficiency if vertebral artery flow is compromised.

- Numbness or paresthesia (tingling) in the hand and/or fingers.

- Sharp, shooting pains (lumbago-like pains) in the neck, back of the head, temple, frontal part of the head, shoulder, arm, or fingers, suggestive of nerve root irritation (radiculopathy).

Treatment of Pain in the Neck, Head, and Arm (Context of cervical degenerative disc disease)

The management of pain in the neck, head, and arm, particularly when associated with conditions like cervical degenerative disc disease, trauma, or ligament/muscle sprains, involves a multifaceted approach tailored to the individual patient's symptoms and underlying pathology.

Initial Management and Conservative Therapies

- Pain Relievers: Over-the-counter analgesics like acetaminophen or NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) are often the first line for pain relief.

- Muscle Relaxants: May be prescribed for short periods to alleviate acute muscle spasms.

- Heat or Cold Applications: Applying heat (e.g., warm packs, heating pad) can help relax tense muscles and reduce pain. Cold therapy (e.g., ice packs) can help reduce acute inflammation and swelling, especially after an injury.

- Activity Modification: Avoiding activities that aggravate neck pain and maintaining gentle range of motion.

- Cervical Pillow: Using a supportive pillow designed to maintain neutral neck alignment during sleep.

Pharmacological Treatment

Depending on the severity and cause of pain, prescription medications may include:

- Stronger NSAIDs or analgesics.

- Short courses of oral corticosteroids for severe inflammation (used cautiously).

- Medications for neuropathic pain (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin) if radicular symptoms are prominent.

Interventional Pain Management (Therapeutic Injections / Blockades)

For persistent or severe pain, therapeutic injections administered by an experienced neuropathologist or neurosurgeon can be beneficial. These are often performed when usual treatments for acute or chronic neck pain (e.g., associated with cervical degenerative disc disease) do not provide lasting positive effects. Common types include:

- Trigger Point Injections: Injection of local anesthetic (e.g., novocaine/procaine, lidocaine) with or without a corticosteroid into painful muscle trigger points.

- Cervical Epidural Steroid Injections: To reduce inflammation around nerve roots.

- Facet Joint Injections: Injection of local anesthetic and a corticosteroid (e.g., cortisone, diprospan/betamethasone, Kenalog/triamcinolone) into or around the cervical facet joints if facet arthropathy is a significant pain generator. Sufficiently low doses are typically used.

- Occipital Nerve Blocks: For cervicogenic headaches originating from the occipital nerves.

When combined with a properly selected physiotherapy regimen, these injections can have a good and long-term effect on headaches and neck pain.

In the treatment of neck pain and degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine, physiotherapy helps to eliminate swelling, reduce inflammation and soreness, and restore the range of motion in the joints and muscles of the neck.

Manual Therapy and Physiotherapy

- Manual Therapy: Techniques such as cervical manipulation or mobilization, performed by a qualified chiropractor, osteopath, or physical therapist, can help relieve pain, improve joint mobility, and reduce muscle tension in some cases. Non-surgical "reduction" of a vertebral disc herniation using specific muscle, articular, and radicular techniques may be attempted by some practitioners.

- Physiotherapy (Physical Therapy): A crucial component, including:

- Specific exercises for neck strengthening, stretching, and range of motion.

- Postural correction and education.

- Modalities like heat, cold, ultrasound, TENS.

- Cervical traction (e.g., using a Glisson loop or manual traction during sessions).

Acupuncture

Acupuncture involves the insertion of thin needles into specific points on the body and can be effective in relieving pain, improving blood circulation, relaxing muscles, and releasing the body's natural pain relievers (endorphins).

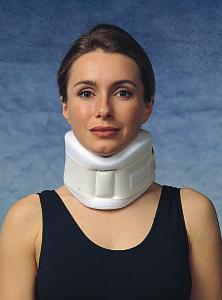

Cervical Braces (Collars)

Wearing a cervical brace (e.g., soft collar like a Shantz splint, or a more rigid Philadelphia collar) for neck pain, particularly that associated with cervical degenerative disc disease or acute injury, helps to limit the range of motion of the neck. This immobilization can provide rest to injured or inflamed tissues, create additional unloading of tense and defensively spasmodic muscles, and thereby reduce pain. Against the background of wearing a cervical collar, the patient's pain symptom in the neck area often resolves much faster, leading to a quicker restoration of the previous volume of head and neck movements. The duration of wearing a cervical brace depends on the severity of the pain symptom and is determined by the attending physician; it can range from several days to several weeks. In a cervical brace, the patient can also sleep and go about their normal daily activities, with appropriate modifications. There are several types of neck braces, all selected by size, and they can be used repeatedly in case of recurrent neck pain.

Wearing a soft cervical brace, such as a Shantz splint, can be part of the treatment for neck pain and degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine, providing support and limiting painful movements.

A more rigid cervical brace, like a Philadelphia collar, may be used in the treatment of neck pain and degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine for greater immobilization and support.

Surgical Treatment (When Indicated)

More serious cases, such as those with significant nerve root compression (radiculopathy) or spinal cord compression (myelopathy) due to a large disc herniation, severe spinal stenosis, or instability, that do not respond to conservative management or involve progressive neurological deficits, may require surgical intervention. Cervical spine surgery is constantly progressing and can yield good results in appropriately selected patients. Procedures may include anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), artificial disc replacement, or posterior cervical decompression/fusion.

Differential Diagnosis of Neck, Head, and Arm Pain

Pain in the neck, head, and arm can arise from various sources. A thorough differential diagnosis is essential:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Cervical Myofascial Pain Syndrome / Muscle Strain | Localized neck/shoulder pain, trigger points, stiffness, often related to posture or overuse. Pain may refer to head or arm in non-dermatomal patterns. Neurological exam usually normal. |

| Cervical Radiculopathy (Pinched Nerve) | Sharp, shooting, or burning pain radiating down the arm in a specific dermatomal pattern. May have associated numbness, tingling, and/or weakness in that distribution. Positive Spurling's test. Caused by disc herniation or foraminal stenosis. |

| Cervical Facet Joint Syndrome / Spondyloarthrosis | Axial neck pain, often dull and aching, may refer to head, shoulder, or interscapular area. Pain worse with extension and rotation. Tenderness over facet joints. |

| Cervical Discogenic Pain (without radiculopathy) | Axial neck pain, sometimes referring to shoulder/arm, from degenerated disc. Pain often worse with flexion or prolonged sitting. |

| Cervicogenic Headache | Headache originating from cervical spine structures (upper facet joints, muscles). Often unilateral, starting in neck/occiput and spreading to frontal/temporal regions. Provoked by neck movements or sustained postures. |

| Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) | Compression of brachial plexus and/or subclavian vessels in the thoracic outlet. Arm pain, numbness, tingling (often ulnar distribution), weakness, vascular symptoms (color/temperature changes). Provocative tests for TOS positive. |

| Shoulder Pathology (e.g., Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy, Impingement, Arthritis) | Pain localized to shoulder, often worse with specific arm movements (e.g., overhead). May refer pain down the arm or up to the neck. Specific shoulder examination tests are positive. |

| Peripheral Neuropathy (e.g., Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, Cubital Tunnel Syndrome) | Pain, numbness, tingling in specific peripheral nerve distributions in the arm/hand. Positive Tinel's or Phalen's signs. EMG/NCS can confirm. |

| Fibromyalgia | Widespread musculoskeletal pain, including neck and shoulders, multiple tender points, fatigue, sleep disturbances. |

| Serious Pathologies (Red Flags) | Tumors, infections (epiduritis, discitis), fractures, myelopathy. Require urgent investigation. Associated with systemic symptoms, progressive neurological deficits, history of cancer/trauma. |

Prevention and Lifestyle Adjustments

Many cases of neck, head, and arm pain can be prevented or minimized through:

- Ergonomics: Maintaining proper posture while sitting, standing, and working. Adjusting workstation (desk, chair, monitor height) to support neutral spine alignment.

- Regular Exercise: Strengthening neck, shoulder, and core muscles, and maintaining flexibility.

- Proper Sleeping Position: Using a supportive pillow that keeps the neck in a neutral position.

- Avoiding Prolonged Static Postures: Taking frequent breaks to move and stretch, especially during sedentary work.

- Stress Management: Techniques like mindfulness, yoga, or meditation can help reduce muscle tension.

- Safe Lifting Techniques.

- Avoiding Phone Cradling: Using a headset or speakerphone instead of holding the phone between the ear and shoulder.

When to Consult a Specialist

It is advisable to consult a healthcare professional (e.g., general practitioner, neurologist, neurosurgeon, orthopedic specialist, or physiatrist) if:

- Neck, head, or arm pain is severe, persistent (lasting more than a few days to a week), or progressively worsening.

- Pain results from a significant trauma or injury (e.g., fall, car accident).

- There are associated "red flag" symptoms:

- Fever, chills, unexplained weight loss.

- Progressive neurological deficits (weakness, numbness, clumsiness in arms/legs, difficulty walking).

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction.

- History of cancer.

- Severe night pain.

- Pain radiates down the arm, especially if accompanied by significant numbness, tingling, or weakness.

- Symptoms significantly interfere with daily activities, sleep, or work.

- Self-care measures do not provide relief.

An accurate diagnosis by a specialist is crucial for developing an effective treatment plan and ruling out serious underlying conditions.

References

- Childs JD, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, et al. Neck pain: Clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(9):A1-A34.

- Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. BMJ. 2007 Mar 10;334(7592):527-31.

- Cohen SP. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of neck pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Feb;90(2):284-99.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Vol. 1. Upper Half of Body. 2nd ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1999. (Chapters on neck and shoulder muscles)

- Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy. A population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain. 1994 Apr;117 ( Pt 2):325-35.

- Bogduk N, Govind J. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009 Dec 24;361(26):2549-56.

- Sterling M. Whiplash-associated disorder: musculoskeletal assessment and physical treatment. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(4):E93-E100.

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec 15;380(9859):2163-96. (Highlights burden of neck pain)

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome